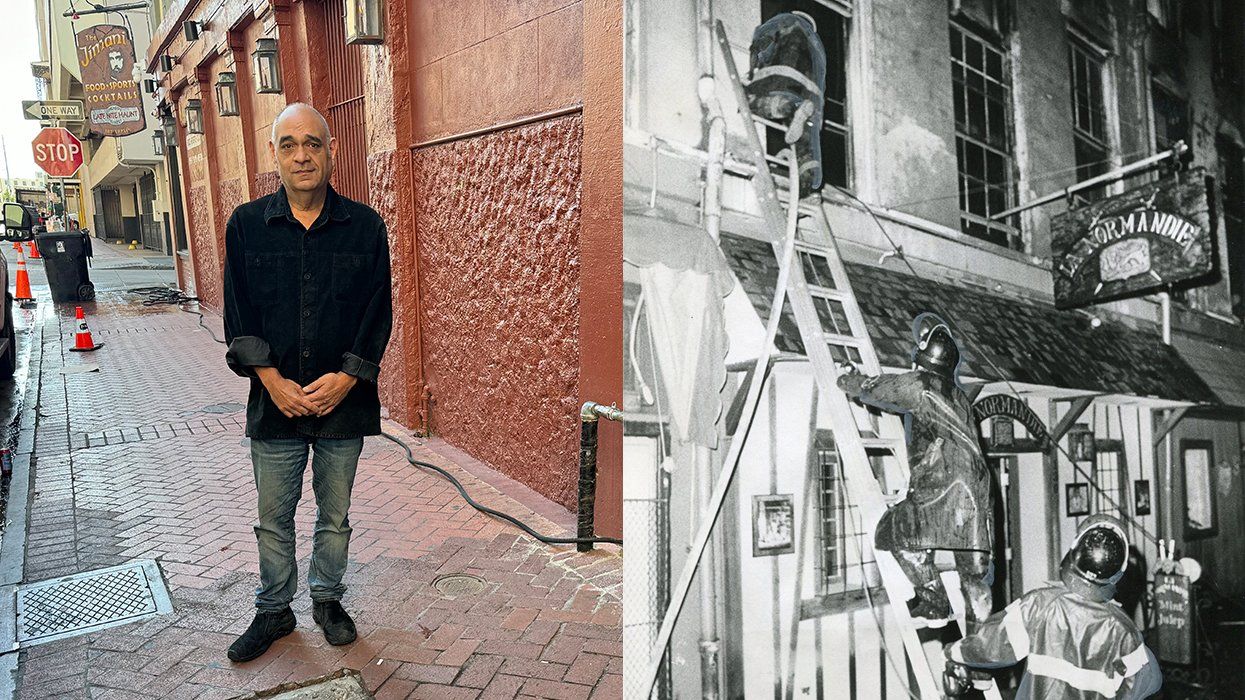

Along Iberville Street in New Orleans’ French Quarter, there’s a large, square gap in the brick sidewalk. The empty space reminds Frank Perez of being in the closet.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

“I’m old enough to remember when it was not okay to be gay,” said Perez, head of the LGBTQ+ Archives Project of Louisiana, during a recent visit. “That’s what the hole in this sidewalk reminds me of.”

The space used to bear a flat, bronze plaque emblazoned with the names of victims who died in the city’s Upstairs Lounge gay bar fire in 1973.

But in April, it was stolen. A man has been arrested and charged with theft, but the original marker remains missing, likely sold as scrap metal.

With the help of other local activists, Perez has launched a fundraising campaign to replace the marker. The group’s aim is to make sure the memory of what happened there isn’t forgotten.

“This was a seminal moment in our local history,” Perez said. “And especially given our current political climate, it's very, very important to remember what happened here and the city's reaction to it.”

The fire remains one of the country’s deadliest attacks on the LGBTQ community. It was the largest up until the Orlando Pulse Nightclub shooting in 2016. In all, 32 people died. Three victims are still unidentified.

The lounge sat on the second floor of a commercial building in a bustling area of town. It was a hub for working class gay men, but it was also known for being welcoming to people of all stripes.

“It was a bar that didn't care if you were black or white or gay or straight,” Perez said. “And even in the LGBTQ community at the time, that was different.”

Prior to the blaze on Sunday, June 24, 1973, patrons had gathered for the bar’s weekly beer bust. As the party was winding down, a fight broke out between two regular customers.

Bartenders kicked one of the patrons out for being too drunk and for making threats.

“He then actually walked a block away to the Walgreens at the corner of Iberville and Royal, bought a can of lighter fluid, came back, and set the stairwell on fire,” Perez alleged.

The flames quickly traveled up the stairwell and into the bar, killing dozens within minutes, according to local news reports from the time.

Firefighters responded, and local media covered the initial tragedy. But overall, the city was mostly “hush-hush” about the fact that the Upstairs was a gay bar, Perez said.

“There was no day of mourning,” Perez said. “There were no public outcries. The only official who really said anything was the Archbishop of the Catholic Church. And all he said was that there would be no Catholic funerals for anyone who died in the bar.”

Local radio broadcasters even joked about the deaths.

“One said. ‘You know, ‘What do we bury the remains in? Punchline: Fruit jars,’” Perez said.

About 30 years later, a group of local advocates worked to have a plaque installed on the sidewalk right outside of the stairwell leading up to the bar. And New Orleans gradually evolved into a more tolerant city.

In 2022, city officials issued a formal apology to the victims and community. They also pledged to exhume the remains of Ferris LeBlanc, a WWII veteran who died in the fire and was buried in an unmarked city grave, and give him a proper burial.

While Louisiana regularly ranks as one of the least LGBTQ-friendly states, New Orleans’ queer scene is thriving. The city boasts over a dozen gay bars and hosts the annual Southern Decadence festival.

So, in April 2024, the community was shocked when the plaque disappeared.

Soon after, New Orleans police released a video of the theft taken from a nearby security camera. It shows a man, later identified as 40-year-old Dannie "Tank" Conner Jr., prying the plaque from the sidewalk.

After loosening the bronze square, Conner lifts the marker into a garbage bin before rolling it away.

Police arrested Conner in Sept. on charges of theft, and he remains in jail. Police haven’t given a suspected motive, but Conner’s criminal history includes a conviction for burglary in 2006.

In 2021, he was charged in neighboring Jefferson Parish as a felon in possession of a firearm but found not guilty. A judge revoked his probation and issued a warrant for his arrest the next year for failing to follow a court-ordered substance abuse treatment plan.

When Perez first saw the video of Conner stealing the plaque, he wasn’t sure whether the theft was hate-motivated or basic theft.

“I was horrified,” he said. “I wasn’t sure what to make of it, but I knew that this demanded immediate attention.”

Since then, Perez has set up an online fundraiser with the help of the Metropolitan Community Church, a local queer-affirming congregation. Their goal is to raise $20,000 to make a new plaque, buy insurance and set aside some cash to pay for future commemoration ceremonies.

The hope is to dedicate a new plaque during a ceremony at the site during Pride in 2025.

“It'll be a well-promoted and well-attended event,” he said. “Remembering queer history and preserving queer history is a form of resistance.”