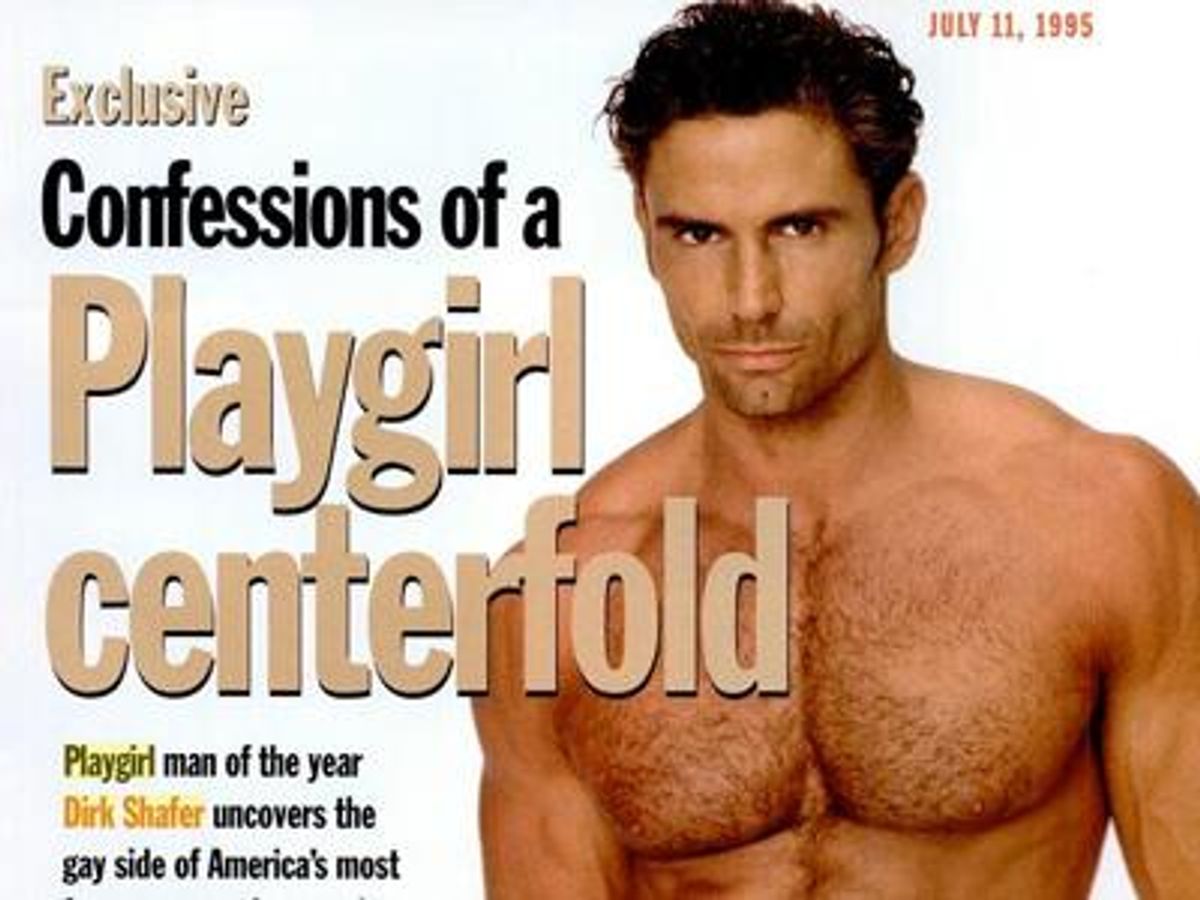

Confessions of a Playgirl Centerfold

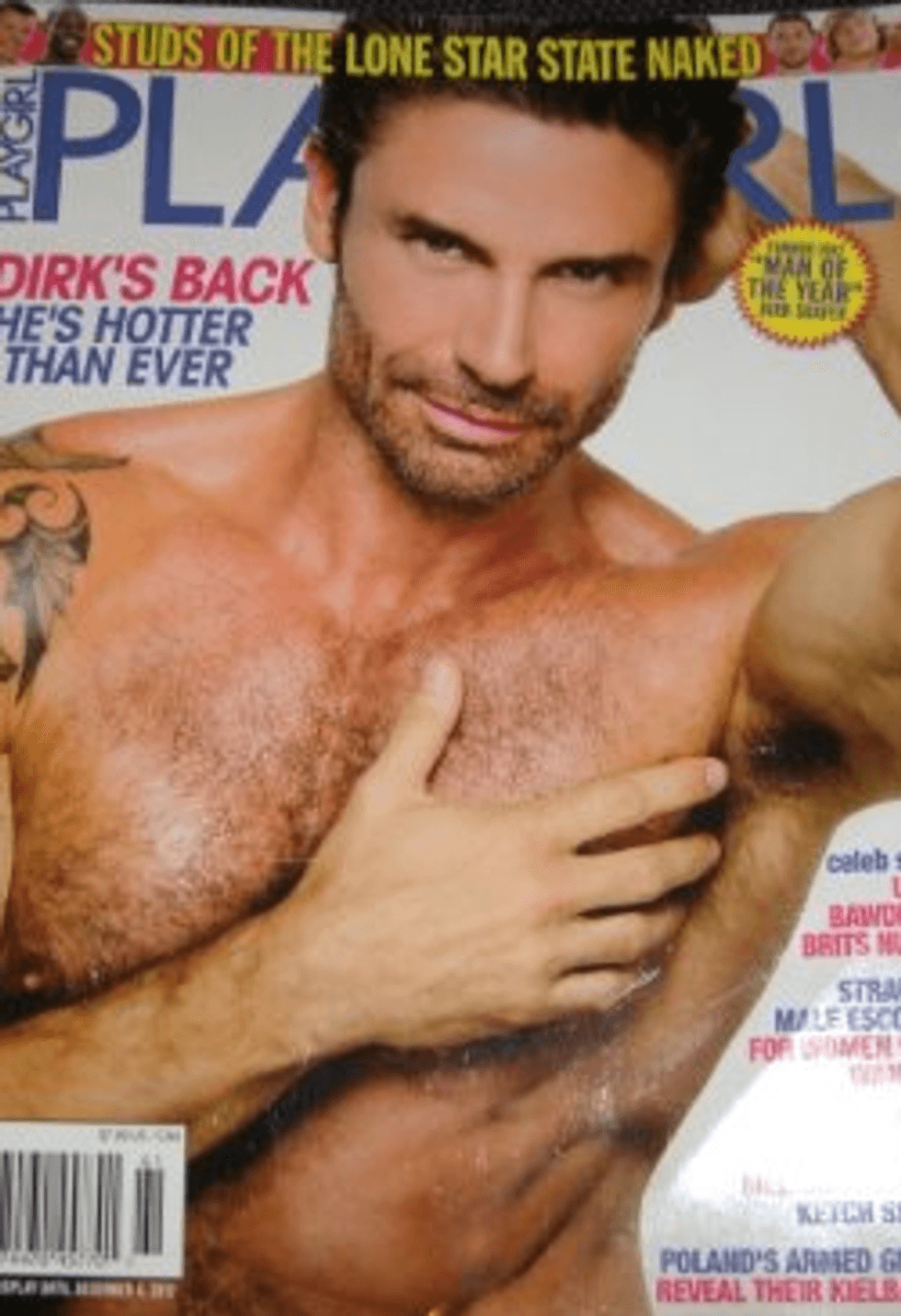

Man of the Year Dirk Shafer uncovers the gay side of America's most famous women's magazine

When the call came from Playgirl informing Dirk Shafer that he'd been selected as the magazine's 1992 Man of the Year, Shafer was quite naturally pleased. "I love to win awards of any kind," he says with disarming candor.

Indeed, who doesn't? But the man-of-the-year mantle wasn't simply an honorific: The terms of his reign would include a year's salary as renumeration for various personal appearances and efficient manning of a 900 number; appearances on talk shows, then at the height of their dubious popularity, would pay extra.

But there was a fly in the ointment: Shafer is gay. And he knew the magazine, whose cover rather pointedly declared itself to be ENTERTAINMENT FOR WOMEN, would not be interested in hitching its well-oiled publicity machine to a homosexual, however wholesome an image of glowing Midwestern sexuality he might exude from the printed page.

"At what point does someone who's taking a job have to come forward and say, 'Hey, I'm gay -- is that OK with you?'" Shafer asks, recalling the unlikely occasion for this moral conundrum. "And I looked at this as a job. I was an actor playing a part, really. It just happened to be based on a sexual image."

He signed on the dotted line.

Shafer, 32, had come to Los Angeles in 1985 from Oklahoma and joined the ranks of aspiring amateurs. Between industry jobs as "everyone's assistant," he'd logged stints as a personal trainer, ballroom-dancing instructor, and caterer.

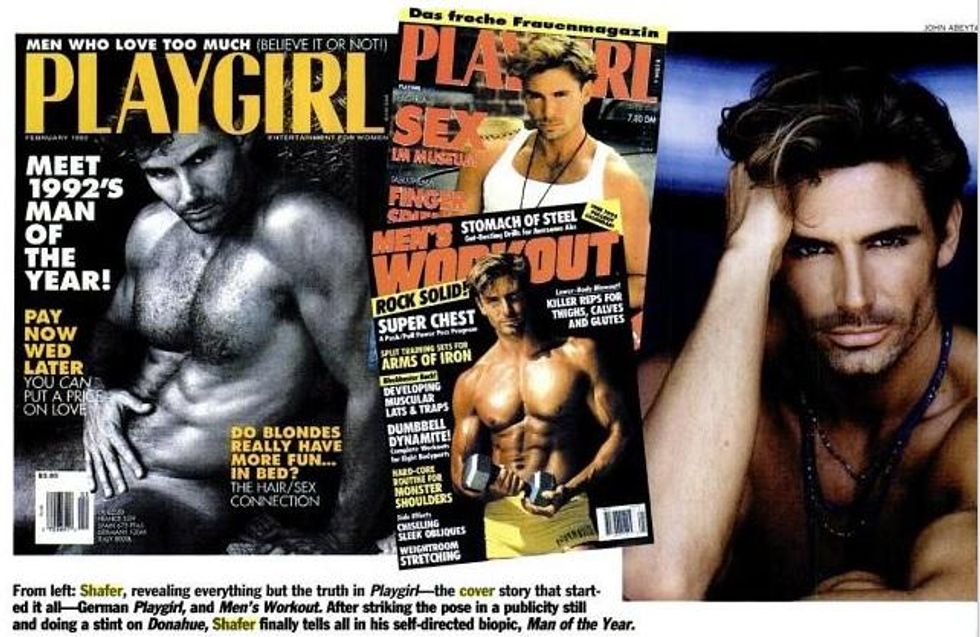

He had first posed for Playgirl at the suggestion of his friend Vivian Paxton, reasoning that a little exposure, as it were, would be good exposure. And indeed, he had dabbled in deception on the occasion of that first layout, as 1990's "Man for the Holidays." It's manifestly unlikely that Shafer's favorite book was Dear Abby's Guide to the Perfect Wedding, as the stats beneath a particularly becoming shot of his naked rear inform. And the choice of Don Rickles and Bonnie Franklin as his "fave" actor and actress -- and Jaws 3-D, no less, in the cinematic category -- could only be a gay man's desperate stab at the camouflage of tastelessness.

But a few fudged faces were small beer compared to the dance of dissonance Shafer embarked on as Man of the Year. With plasticine smile firmly in place and boyfriend Michael Mueller secretly in tow, he jetted from Jenny Jones to the Jerry Springer Show, from Sonya Live to Donahue, everywhere billed as the walking, talking embodiment of every woman's fantasies.

"At first I just approached it as a lark," he remembers. "But then when I'd see myself on the screen with the words SAYS HE KNOWS WHAT WOMEN WANT underneath my name, I thought, Wow, I'm getting in deep here."

Sophisticated viewers of The Joan Rivers Show might have guessed that the coiffed blond with the tanned body bulging from under a sleeveless lumberjack shirt was perhaps not the world's foremost authority on what turns women on, but ironically, Shafer took the role more seriously than a hetero hunk might have. "I asked all my girlfriends what they wanted in a man, what them on, what they looked for in men," Shafer says. "And I used all the experience from the 900 number to draw on -- I had painstakingly logged all the most interesting comments."

He even kept up the mask after hours. "When there would be 20 hunks on some show, we'd all be booked in the same hotel, and they'd want to go out drinking and chasing women all night," he recalls. "So I'd dutifully go out with all the other hunks, chasing women -- the last thing I wanted to do in New York."

It wasn't long before his conscience began to kick in. And his travels came complete with a set of vengeful furies in the form of gay activists who had his number and didn't care for his act. "Gay people were coming up to me and saying, 'I think what you're doing is terrible.'" Shafer says. "I didn't know what to say. And I was always afraid that at some talk show they'd take a question from the audience, and some guy would stand up and say. 'I slept with you!'"

Shafer managed to escape such a sensational undoing, but his moral equilibrium gradually began to falter: "Here I was, standing on a pedestal for male heterosexuality, and I started thinking, Wait a minute: There's no one doing this for gay people. There's no one standing up and saying it's OK to be gay and out. It made me feel guilty. I was left thinking, Is what I did the right thing, or is it the wrong thing? Should I have said no? I'm not taking this job because I'm misrepresenting myself. But just because Rock Hudson was gay, should have have not been in Giant? The more torn and confused I was, the more I started thinking that this was a great conceit for a movie. It was an interesting story to tell.

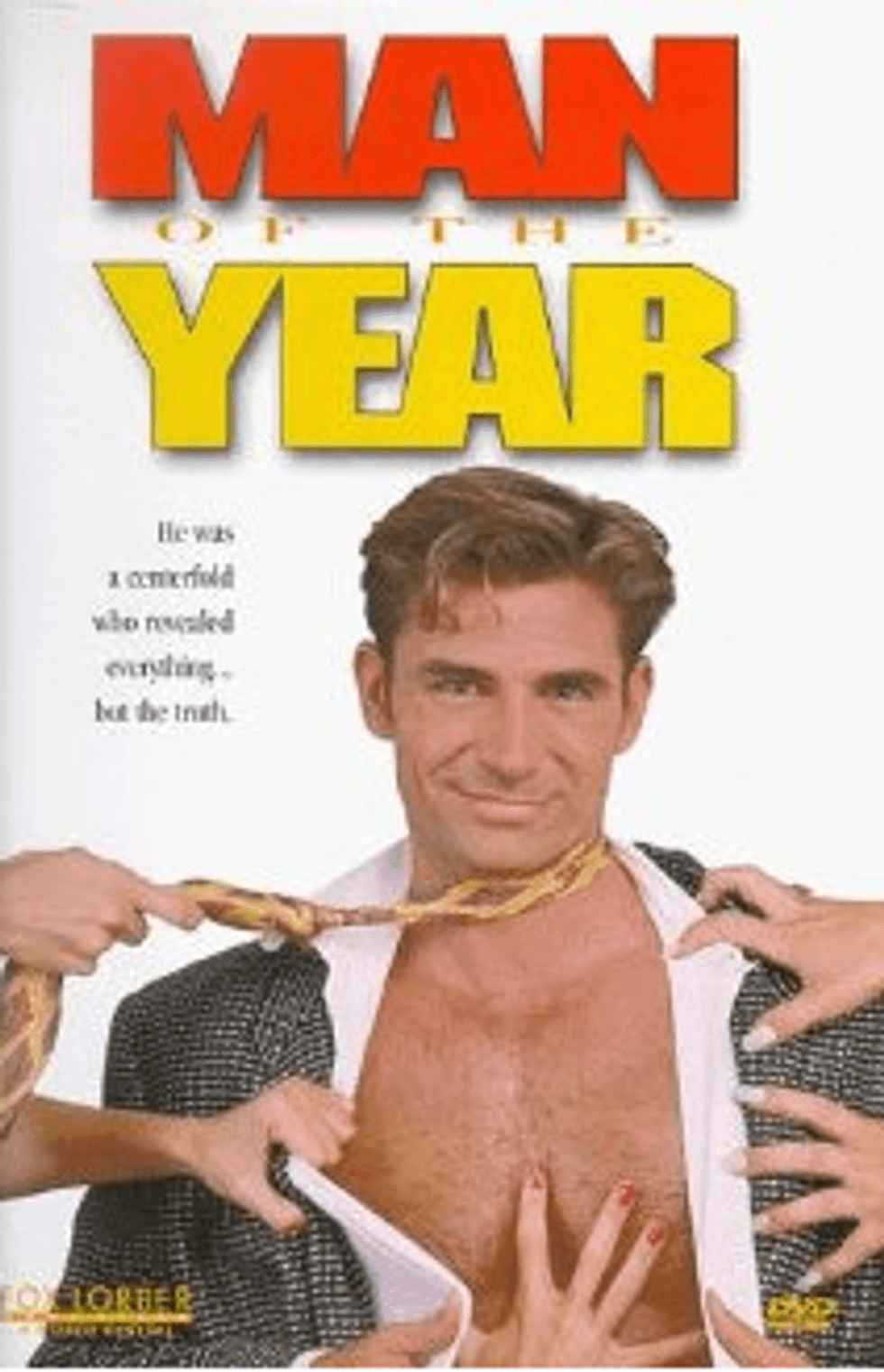

And so the urgings of his conscience collaborated with his artistic impulses, and a screenplay was born. In mock-documentary style, Shafer set out to re-create the saga of the centerfold with a secret. He and producer Matt Keener initially knocked on Hollywood's door.

"When we started pitching it to Hollywood development executives," Shafer relates, "they'd get enthusiastic: 'We love it! But can you just change one thing?' they'd say. 'Does he have to be gay?' I'd say, 'There's no story if he's not gay.' They'd say, 'It could be a religious thing. He's Amish or something.'"

So much for Hollywood. But Shafer and Keener were undaunted. "I went to everyone I knew for money," Shafer says flatly. "I even started cold calling. If I heard a friend say he knew someone who had just made some money, I would be on the phone saying, 'You don't know me, but I'm doing this film...' There was no other way. I had to do the movie."

With deferred salaries for virtually all the cast and crew, wihich included Mueller as production designer and Paxton as makeup artist and costar, the movie, titled Man of the Year, was shot in 13 days. But money ran out in postproduction. Reenter Hollywood, in the form of Forrest Gump producer Steve Tisch, who saw a rough cut of the movie at the behest of Shafer's manager, Keith Addis.

"I really enjoyed the cut that I saw, and so a few of us put up the money to finish the picture," explains Tisch, who went on to cohost a screening of Man of the Year for industry execs. "The feedback I got was extremely positive. And ultimately, I hope it will get a distributor. But more important, I think we made a lot of people aware of Dirk Shafer as a filmmaker."

Although the movie has been selected as the July 16 closing-night film at the Los Angeles International Gay & Lesbian Film & Video Festival and is likely to be much sought-after on the gay-festival circuit, Shafer believes his story is one that has universal appeal. "What I went through is really a situation that everyone goes through," he says, smiling at the statement's apparent absurdity. "At some time or another, everyone has to hide behind a mask, present themselves in another way and be accepted. A girl saw the movie and said, 'This is my story -- every day I have to be a different person to go to work. I have to put on a mask to get through my job.' It's a concept everyone can relate to."

But what of Playgirl, whose Man of the Year wasn't the man he so telegenically appeared to be? Did the magazine have an inkling of Shafer's predicament? Shafer says they never asked about his sexuality. "I don't know if they cared or not." he says. "It was obviously important to present the image they wanted me to present, and I did that. My real sexuality was never mentioned."

Charmian Carl, Playgirl's publisher, gives Shafer high marks. "He was one of the best men of the year we've had," she says. "He did a very good job for us -- and even went beyond our expectations." She recognizes the respect he maintained for the magazine's position: "We do want the men representing the magazine to speak to women and their interests, to speak comfortably about women's desires. The man of the year is a woman's fantasy figure; if he says he's gay, he blows the fantasy! But Dirk understood and respected that."

Shafer's odyssey made interesting counterpoint to a larger issue that has hovered about Playgirl since its inception more than 20 years ago: the magazine's undeniable though largely unacknowledged appeal to gay men. When Playgirl began publishing in 1973, it was perceived as a bold assault on cultural conventions that held that women's sexuality was exclusively an adjunct of men's desires. In the publishing world the translation was simple: Women posed; men looked. Playgirl turned the equation around, putting male bodies on the other side of the staple for the first time in mass-market publishing and printing editorial material that would make a Cosmo girl reach for the smelling salts.

"We had trouble convining the world that women would want to look at nude men," says Ira Ritter, the magazine's first publisher, "until our first issue sold 600,000 copies."

Although in the founding years, Ritter says, the existence of a large gay readership "was not in our consciousness" the scope of the magazine's reach and its singular status as the only "respectable" magazine that happened to feature male genitalia in the editorial mix made such a following an inevitability. Indeed, by the late '70s, when Neil Feineman joined the magazine's editorial staff, the magazine's gay readership had become an issue whose significance was underlined by the strenuousness with which the topic was avoided."

"The big unspoken issue at the magazine was always the question of the gay readership," says Feineman, "and the editorial fight about whether to cater to them or to pretend they didn't exist. People talked about it constantly, though not officially. They used to say 10% to 12% of the readers were male, but my theory was that it was at least 40%, and I wasn't alone in this. There was subscription info that led us to believe that."

Randy Dunbar, an art director at Playgirl's publishing company during the same period, agrees. "They said they had a 7% to 11% gay readership -- which of course was not true at all," he says. "It was the kind of thing they didn't want to acknowledge. They played down the numbers."

Randy Dunbar, an art director at Playgirl's publishing company during the same period, agrees. "They said they had a 7% to 11% gay readership -- which of course was not true at all," he says. "It was the kind of thing they didn't want to acknowledge. They played down the numbers."

The magazine's ambivalent attitude about its gay readershp was fueled not by any overt homophobia on the part of the publishers, Dunbar and Feineman believe, but by economics. "What's important for magazines is not readership; it's the perceptions of the advertisers," says Dunbar.

"The thinking at the time -- and gay alternative magazines have since disproved this -- was that national advertisers wouldn't advertise in a magazine aimed at gay readers," echoes Feineman. "The publishers would say, 'Oh God, we would lose Madison Avenue.' But the truth is that they never had it anyway."

Most frustrating to Feineman were the editorial consequences of the magazine's lack of interest in cultivating its gay audiences. "I always thought that if you had this demographic that has disposable income, taste, etc., why not play to that?" he says. "Instead of aiming at the mythical Midwestern secretary, why not write for the upscale, intelligent demographic that I believed they had? Given the fact that we had a more sophisticated reader than we were willing to admit, why wouldn't we go with better journalism?"

The question of the models' sexuality was also a matter of some debate. Although Ritter says, "I absolutely tried to not choose gay men; I was trying to sell to women," the policy was obviously impossible to enforce.

Nancy Gottesman, who worked briefly at Playgirl in the late '70s, recalls collecting information from a model who was clearly gay: "I went to my editor, not knowing whether this was something they wanted to know, and said, 'You know, I think he might be gay.' She said, 'That's OK, honey, most of 'em are.'"

Feineman recalls rumors that an art director was "casting a lot of the stuff in bathhouses." He also remembers a general air of consternation when one of the magazine's centerfold spokesmen, who was married, later turned up rather spectacularly in gay-porn movies.

The magazine's semiofficial "don't ask, don't tell" stance regarding its gay readership continued when it was sold and moved to New York in 1986. The hazy nature of the policy meant attitudes varied with editors.

Photographer Douglas Cloutier, who claims the distinction of currently being the "longest-running contributor" to Playgirl and has been working for the magazine for ten years, says some editors have nixed models who "appeared" gay. "One editor cared a lot, though I think it had more to do with the upper management than with her," he says. "She would always say, 'He's got that gay mouth. That gay lip.' If anybody looked gayish, they wouldn't get in, though she'd never ask if they were in fact gay."

Model Al Rizzo, who posed for the magazine in the early '90s, says his sexuality only became an issue when it was time to supply the biographical information that's tastefully strewn around the edges of the photographs: "The questions I was asked were questions that meant you'd have to admit you were gay or deny it: 'What kind of girls do you date?' etc. I remember that I just chose to use the words someone and person a lot! I think the interviewer probably knew, but she didn't want to investigate.

Cloutier has observed a considerable thawing of the formerly strained attitudes. "The new publisher-- Charmian --is the best," he says. "She's opened it up a lot: it doesn't matter if the models are gay or not."

Indeed, Carl dismisses the idea that the magazine cares one way or another about the models' sexuality. "It's not of interest to us," she says. She also acknowledges that past attitudes about the gay readership have been unnecessary chilly. In recent years subscriber surveys have even contained questions aimed specifically at male readers, which, she says, make up 12% to 15% of the magazine's readership of 500,000.

"I think we probably did suffer in the past from the 'lady doth protest too much' syndrome on this issue," Carl says. "There was the fear that Sally Smith wouldn't buy the magazine if gay readers were acknowledged; but she is buying it. There's nothing to hide: First and foremost, our goal is to please our female readership, but for the most part we acknowledge and cherish our male readers. I don't want to do anything to turn any readers off."

Considerably less obscure than the magazine's previous attitudes about gay readers are the reasons behind those readers' affection for the magazine. The short answer is the men. In the years following Stonewall, closet doors did not immediately come thundering down in a magnificent wave of liberation sweeping from the cornfields of Nebraska to the Mississippi delta. Across the nation gay men and boys struggled -- as they still do -- to come to terms with their sexuality in the absence of erotic stimulants (unless you count the underwear pages of the Sears catalog -- sadly, now defunct).

Playgirl became a touchstone for a generation of gay men. "Playgirl was a big influence on me as a kid," says Shafer. "I remember sneaking into my neighbor's house to peek at it when I was really young, 9 and 10 years old. And the amazing thing is, all my friends have the same story!"

Playgirl became a touchstone for a generation of gay men. "Playgirl was a big influence on me as a kid," says Shafer. "I remember sneaking into my neighbor's house to peek at it when I was really young, 9 and 10 years old. And the amazing thing is, all my friends have the same story!"

Novelist Scott Heim, 28, writes of the aching comfort it brings to a young Midwestern boy in his novel Mysterious Skin. The episode, in which an 8-year-old boy, already alive to his sexuality, comes upon an issue of Playgirl in the dust beneath his mother's bed, is drawn from life. "I'd wait for my mom to go to bed and every night I'd run to where I knew it was hidden," Heim recalls. "I'm sure that by the end of the month, she knew; it must have been dog-eared. But it was the most amazing feeling, the first time I saw these pictures. It was as if someone has cut a hole in my chest and reached in and grabbed my heart."

Kenny, 22, Appleton, Wis., also came upon the magazine at an early age. "I started to find copies in a neighbor's garage when I was about 10 years old," he says. "And then, through high school, it was the only place where I could explore men's bodies; I certainly couldn't do it in the locker room at school."

And of course, for closeted men of any age, the appeal of Playgirl was the fact that it trumpeted itself as a magazine for women. It's a rather delicious, if sad, irony that while the magazine studiously ignored its gay readers, those readers felt free to buy it precisely because it ignored them. Playgirl could be purchased at the corner store with a grimly sheepish chuckly and a not-so-offhand remark about a wife or a girlfriend at home, and the closet was left intact -- or the illusion was left intact, anyway. A purchaser of Blueboy had no such psychic refuge.

Indeed, it continues to serve that function ably, acting as some sort of pornographic training wheels. Darren Roberts, editor fo the Los Angeles-based gay magazine Edge, was a subscriber in the early '90s. "I was in the closet at the time, and it was the only way short of going into a porn shp to get photos of nude men, and I was too self-conscious to do that," he recalls. "So I went into a bookstore in a mall and asked the girl behind the counter to go get me a Playgirl so I could get a subscription for my sister for her birthday. Of course, I was probably obviously lying, I was so nervous about it. But she did it. And I sent off for a subscritpion."

"The only people I knew who read it were gay men," says Dunbar. "Playgirl allowed a lot of closeted men access to nudity. It was a closet tool, kind of."

And many of those readers continue to look at the magazine even after they've discovered -- or worked up the nerve to seek out -- more overtly homoerotic magazines. "I continue to read it because the grade of man that is in Playgirl is often higher than a lot of gay porn," says Kenny. "I would say the majority of gay men I know who look at skin magazines look at Playgirl. And I know that at the store where I buy mine, 85% to 90% of the purchasers are men."

Comparing Playgirl to your average gay nude magazine does reveal a distinct difference in the manner of presentation. The men in Playgirl are never far from a prop -- however unlikely -- that lends a domestic air to the proceedings. The photographer, it seems, just happened to snap Mike as he sat nude before his computer, brow furrowed in concentration; or Joseph, whipping up that pot of spaghetti without benefit of apron; or Tom, avec tractor. In gay magazines the only props likely to be in evidence are a tablespoon of oil and the model's right hand. The softer touch is key to Playgirl's appeal for men and women.

"According to our polls," says Carl, "the men don't want Playgirl to get too rough-edged. They like to see Playgirl remain at a certain level of social acceptability. What they want from Playgirl is what all of us want; the boy next door, the campus stud, the jock from the volleyball team. The good boy who shows you what he's got and then goes back to being a good boy."

"I think the thrill is that they think they might be straight," says Cloutier. "When we're growing up and forming our fantasies about men in our adolescence, we look around at the guys in the locker room, who are talking about girls. That's how the attraction to straight men happens. It's that old thing -- 'I just want a real man.'"

Los Angeles-based clinical psychologist Mitch Walker, who's worked with gay men for more tha two decades, isn't surprised at this phenomenon. "Internalized homophobia is still a stupendous problem in gay-male psychology," he explains. "It's what's at the root of gay men being attracted to straight men. It's a manifestation of the thinking that straight men are more 'respectable,' that there's something less respectable about being gay."

Whether they use it as a tentative step toward publicly acknowledging their homosexuality or as a ruse to keep from doing so or simply as fodder for idle fantasies of seducing the straight boy next door, gay men will continue to buy Playgirl. Because of its 22-year publishing history, its roots firmly planted in the hallowed ground of feminism, and the perception of it as a woman's version of the eminently respectable Playboy, Playgirl reaches deeper into the fabric of everyday American life than any gay magazine. And wherever it can be found, gay men -- and boys -- will find it.

Shafer can personally vouch for the magazine's continued popularity among gay men. As he relates in Man of the Year, he was somewhat surprised to find that 25% of the callers to his 900 number were male. "And," he adds, "I think men are less likely to call in, thinking the centerfold might be straight since the magazine is aimed at women."

For Shafer his career as a Playgirl pinup par excellence is richly ironic. "Assuming that the guys were straight was initially part of the attraction when I was first looking at Playgirl," he admits. "It comes from adolescence, because I don't find straight men more attractive than gay men now. I think it's because when you were growing up, there weren't any sexy, out , open gay people. There just weren't. The only sexy men around were the straight, beautiful movie stars; that's all that we had to fantasize about and relate to. Now it's so different; there's Bob and Rod, there's Greg Louganis... it's terrific."

Randy Dunbar, an art director at Playgirl's publishing company during the same period, agrees. "They said they had a 7% to 11% gay readership -- which of course was not true at all," he says. "It was the kind of thing they didn't want to acknowledge. They played down the numbers."

Randy Dunbar, an art director at Playgirl's publishing company during the same period, agrees. "They said they had a 7% to 11% gay readership -- which of course was not true at all," he says. "It was the kind of thing they didn't want to acknowledge. They played down the numbers." Playgirl became a touchstone for a generation of gay men. "Playgirl was a big influence on me as a kid," says Shafer. "I remember sneaking into my neighbor's house to peek at it when I was really young, 9 and 10 years old. And the amazing thing is, all my friends have the same story!"

Playgirl became a touchstone for a generation of gay men. "Playgirl was a big influence on me as a kid," says Shafer. "I remember sneaking into my neighbor's house to peek at it when I was really young, 9 and 10 years old. And the amazing thing is, all my friends have the same story!"