Pride Marches From 1969 to Present in 15 Unearthed Images

06/12/20

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

In June 2020, on what would have been the 50th anniversary of official Pride observances, Getty archivists Shawn Waldron and Bob Ahern took a look back at the history of Pride and the LGBTQ+ community's work through the decades.

The Advocate was given an exclusive look at some of Getty Images' unearthed long-forgotten photographs of Pride parades and marches since they began in response to the Stonewall rebellion.

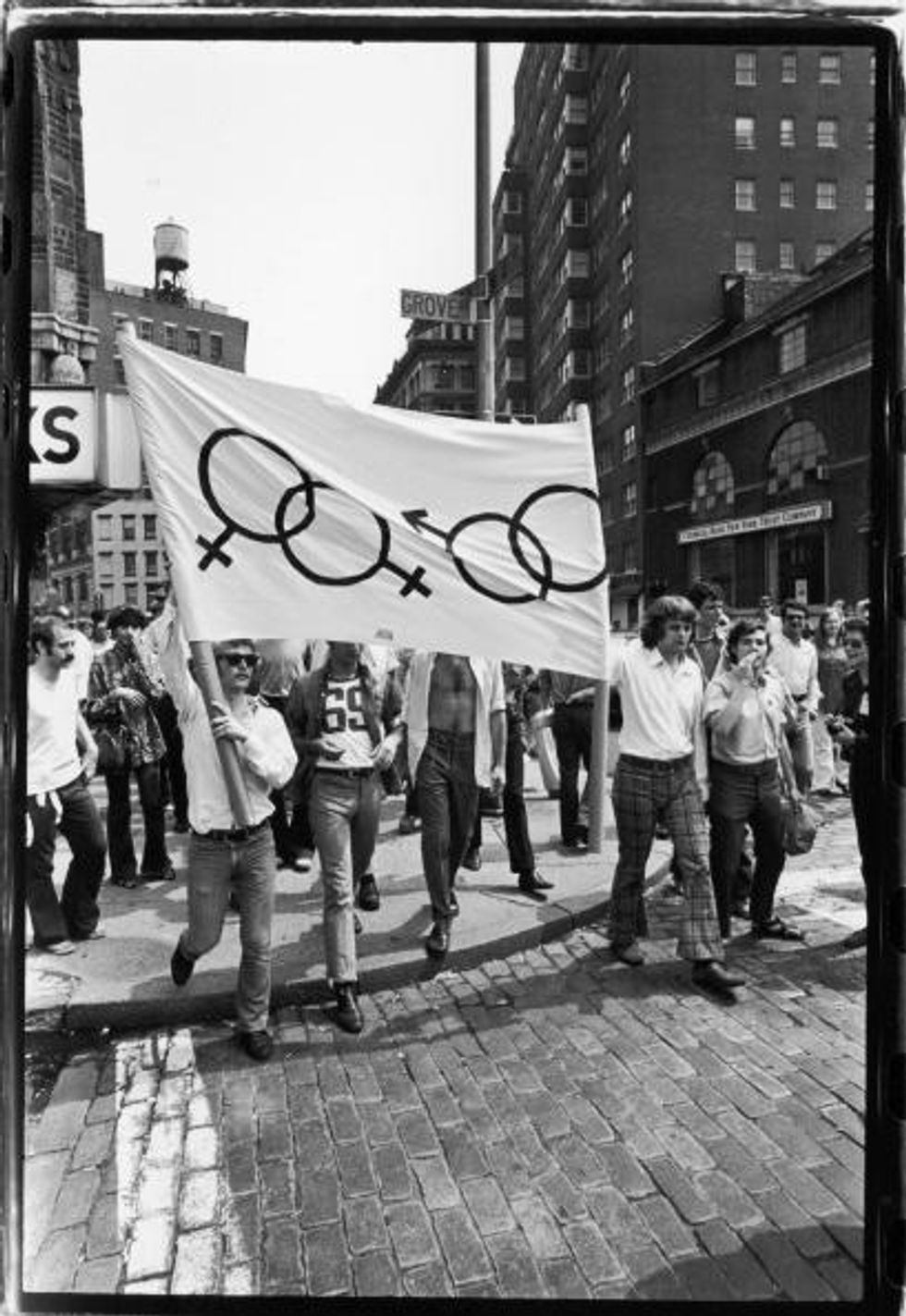

On July 27, 1969, one month after the Stonewall riots, a group of approximately 200 people marched along West Fourth Street in New York City in a show of support for LGBTQ+ rights. The riots' scars had yet to heal, and this was more of a rally than a coordinated march, but it set the stage for what was to come. Fred McDarrah, chief photographer for The Village Voice, had been on site to photograph the riots and followed the story closely for years.

Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

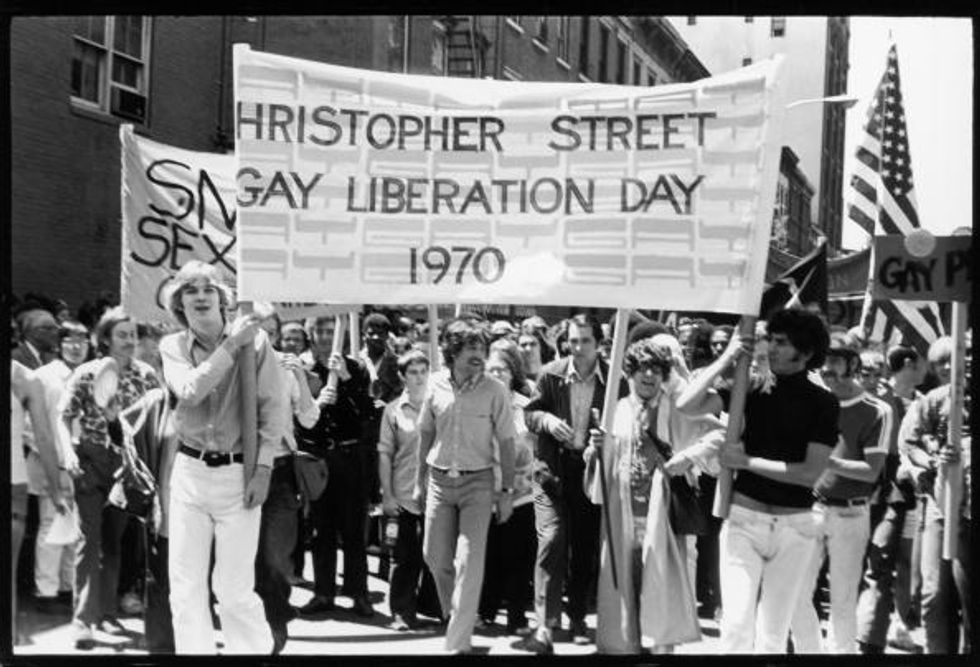

The first official march was held in New York City June 28, 1970, known as Christopher Street Liberation Day. After months of planning involving more than a dozen groups, the group of 2,000 traveled up Sixth Avenue from Waverly Place through midtown ending in Central Park. Craig Rodwell, one of the lead organizers, and activist Foster Gunnison can be seen here leading the way.

Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

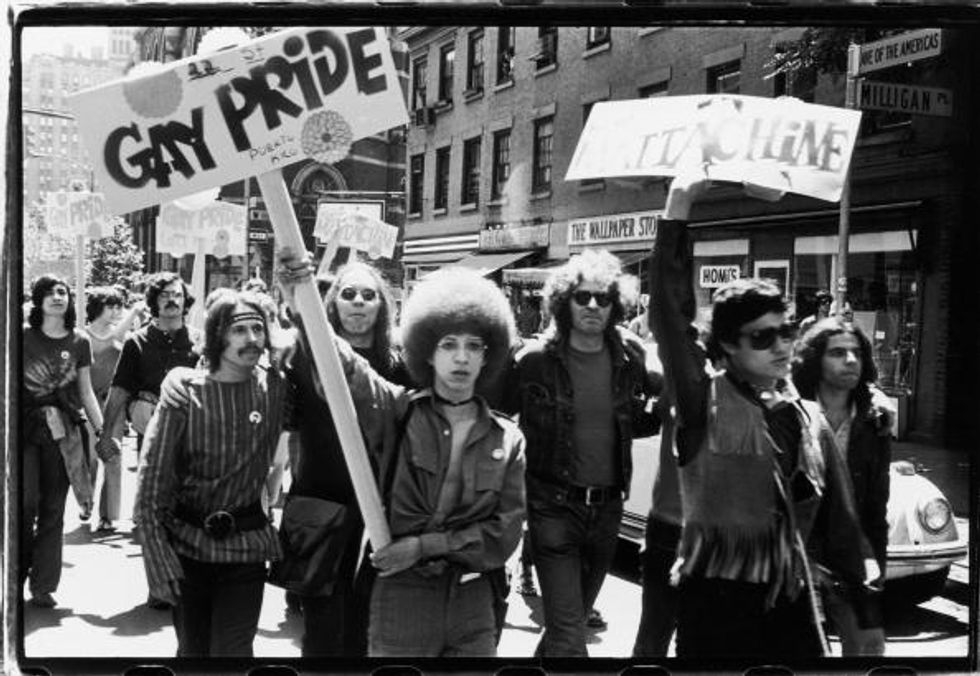

The phrase "Gay Pride" was chosen as a chant during the first march. In keeping with the times, "Gay Power" had been considered, but according to activist L. Craig Schoonmaker, at the time, gay individuals lacked any real power, but they did have pride. In 2015, Schoonmaker further explained, "A lot of people were very repressed, they were conflicted internally, and didn't know how to come out and be proud. That's how the movement was most useful, because they thought, Maybe I should be proud."

Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

Members of Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, were a regular presence at the early marches. STAR was founded by Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson in 1970 to support and shelter young people living on the streets and transgender youth, two groups that were underserved, if not openly rejected, by other support groups at the time. STAR House was pioneering on a number of fronts: It was the first LGBTQ+ youth shelter, the first group led by trans women of color, and the first trans sex worker labor organization. At the post-march rally in 1973, the year this photograph was taken, Sylvia Rivera delivered her candid and contentious "Y'll Better Quiet Down" speech.

Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

By 1974, the march had begun using the more universal name of Gay Liberation Day. The tone was still one of defiance and protest.

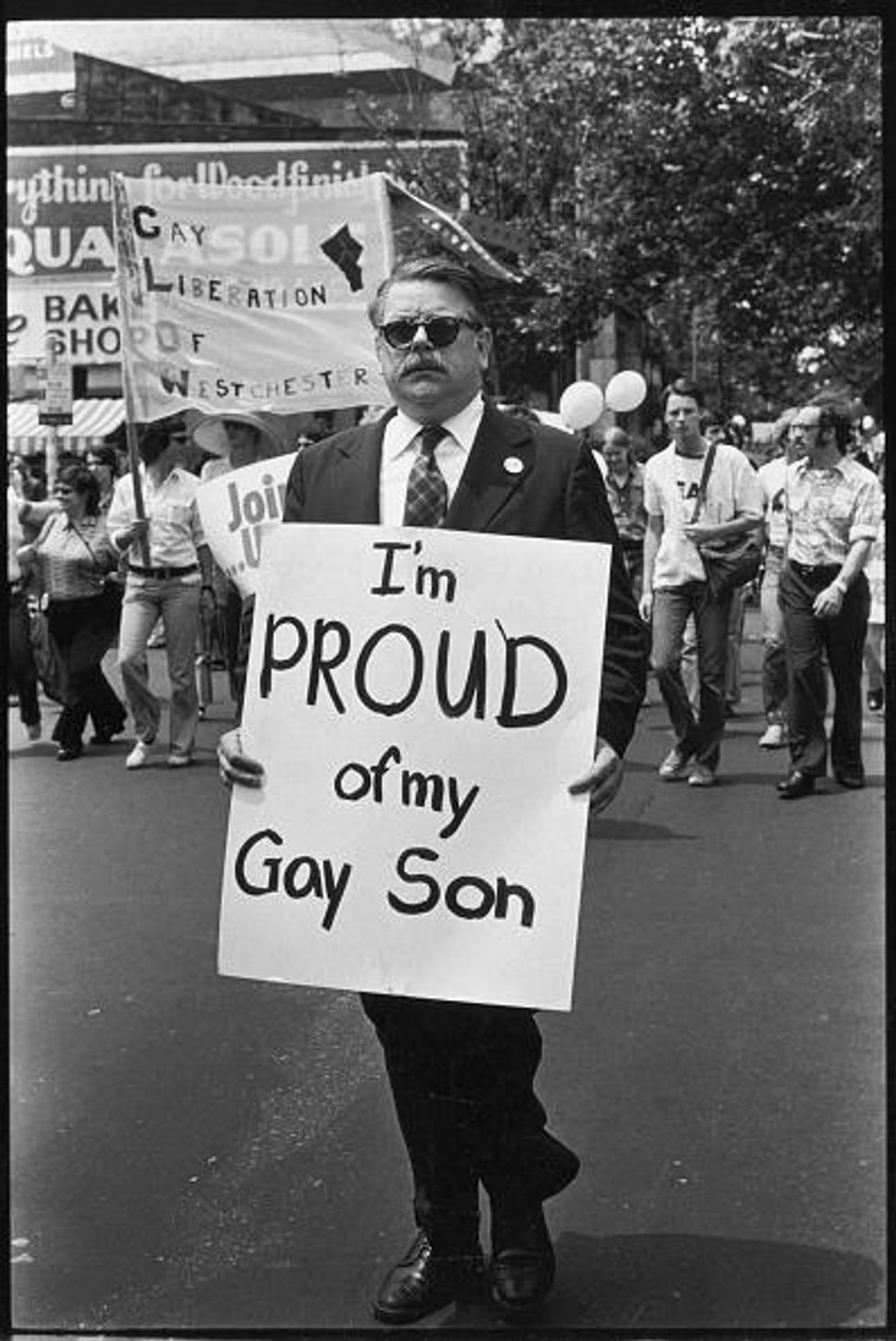

Jeanne Manford marched in 1972 alongside her son Morty, who had recently been badly beaten at a protest. Manford carried a sign reading, "Parents of Gays: Unite in Support for Our Children." The crowd's response to the sign was overwhelmingly positive and inspired Manford to start a local parents' group. Dick Ashworth, seen here marching in 1974, and his wife, Amy, were two early members. Throughout the 1970s, Amy traveled to dozens of cities around the country to start local groups. In 1981, the various groups organized nationally as PFLAG under the leadership of Adele Starr.

Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

By the early 1980s, the annual march was the largest event of its type in the world, with celebrities such as Quentin Crisp, seen here in 1982, and LGBTQ and ally groups from around the U.S. participating. The atmosphere and mood, which had always been positive, began to favor celebration over protest. However, within a year, gay life in New York would face its greatest threat.

Photo: Barbara Alper/Getty Images

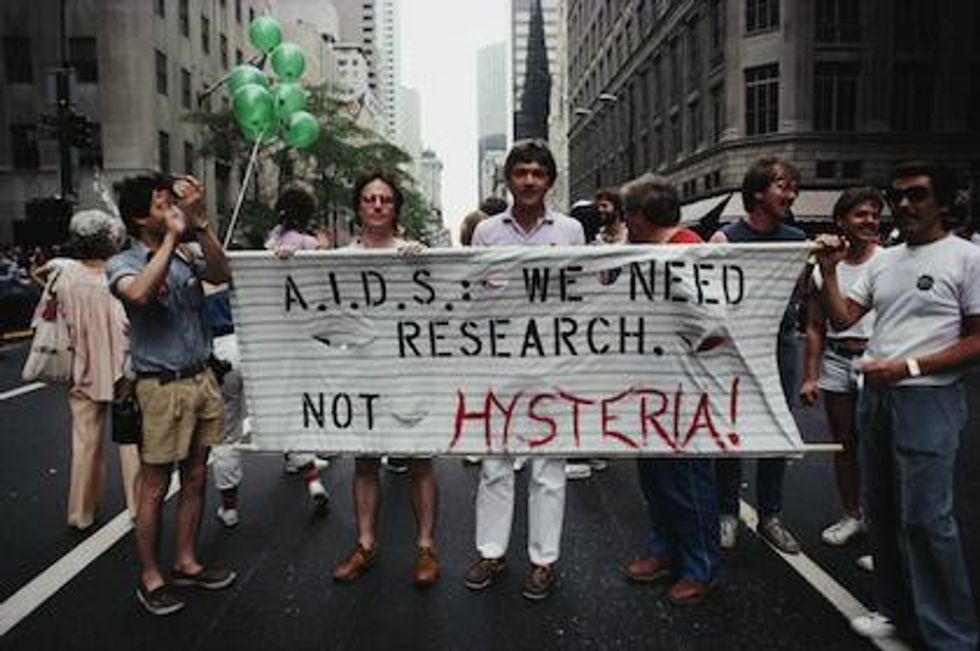

As the 1982 parade was marching up Sixth Avenue, Nathan Fain, Larry Kramer, and others were incorporating the Gay Men's Health Crisis in response to a new disease that was beginning to spread through the gay community. It was officially termed acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention later that summer. The misconceptions, prejudice, and death toll associated with the disease made for years of relatively somber marches, as seen here in this scene from 1983. That same year, the route was changed to a north-south route, beginning in Columbus Circle, traveling down Fifth Avenue, and ending in Greenwich Village. The lavender stripe was first laid down in 1985.

Photo: Barbara Alper/Getty Images

The AIDS epidemic and the response from groups like GMHC and ACT UP, founded by Larry Kramer in 1987, radicalized and politicized the marches again. The organization's pink triangle logo appeared in seemingly every image from this time period, such as this one from 1988.

Photo: Eugene Gordon/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images

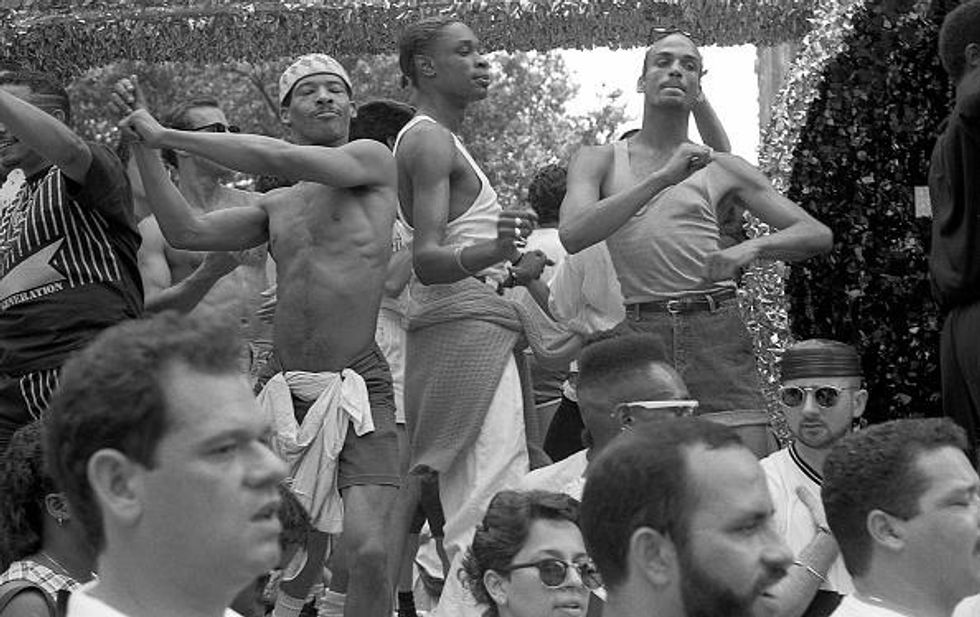

By the time these men floated along the route in 1989, the atmosphere surrounding the march was changing -- the word parade entered the equation -- along with increasing level of attendance and ally support. Pride was born of remembrance and protest, and while those elements remained, celebration and demonstration became a critical part of the experience. The public displays and celebration of the LGBTQ+ community, drawn from an ever-expanding and nuanced spectrum, show the world that this community not only exists but is thriving. The message of freedom is a critical expression of self-love and a show of support to anyone struggling with identity.

Photo: Walter Leporati/Getty Images

Pride continued to grow throughout the 1990s. The large number of participants and spectators helped create truly compelling visuals. During the 1991 edition, members of ACT UP staged a "die-in" in front of St Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. Their demands included increased funding for AIDS research, modifications in the CDC's approach to the disease, and changes to the Catholic Church's position on AIDS prevention and gay life.

Photo: Andrew Holbrooke/Corbis via Getty Images

Thanks to the efforts of Brenda Howard, a.k.a. the "Mother of Pride," every Pride since 1970 has featured a week of associated events in the days leading up to the march itself. One of the longest running is the Dyke March, held the Saturday before the main event. Similar lesbian-only events were held on and off in the '70s; the modern Dyke March was resurrected and formalized by the Lesbian Avengers in 1993 over concerns the main march was losing its political edge and becoming too commercial.

Photo: Evan Agostini/Liaison

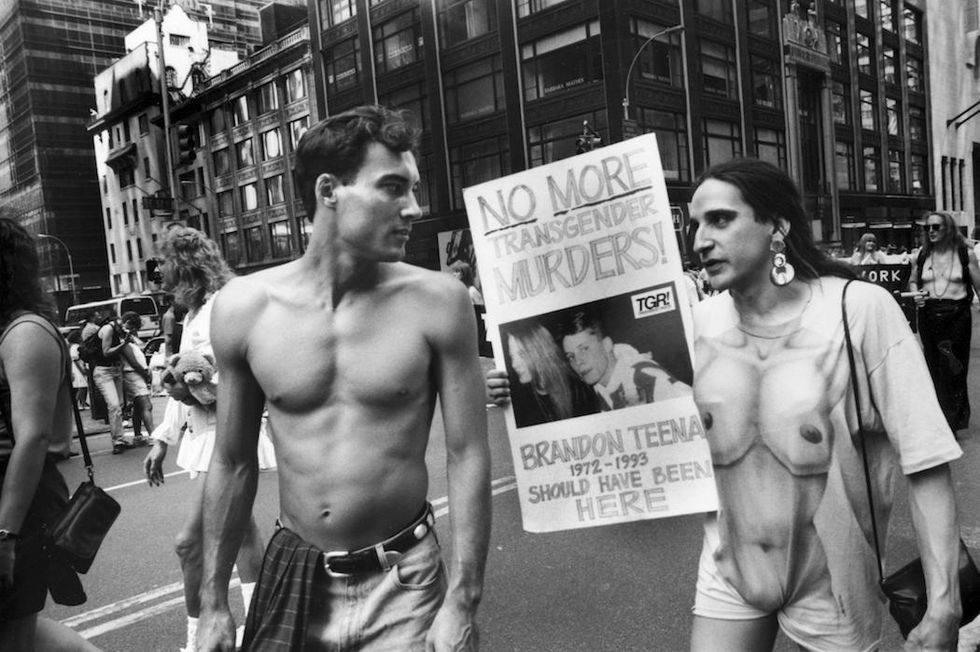

Protests in the 1990s frequently focused on the increasingly public issue of sexual violence and homicides of queer and trans people. Though attacks of this nature had been going on for decades, the murders of Brandon Teena in 1993 and Matthew Shepard in 1998 increased the public awareness of and against homophobic crime. This image from the 1995 Pride is also featured in the book The Gender Frontier by Mariette Pathy Allen, an artist who has been photographing the transgender community for more than three decades.

Photo: Mariette Pathy Allen/Getty Images

Marches throughout the 2000s focused on the long and contentious battle for marriage equality. By June 2004, 4,000 same-sex marriage licenses were issued in San Francisco under orders from its mayor, now California's governor, Gavin Newsom. The same licenses were voided by the California Supreme Court in August. Same-sex marriages were finally legalized across the state in 2013, after a long battle. 2004 also marked the beginning of legal same-sex marriages in Massachusetts, the first state to establish marriage equality.

Pride 2015 was the most celebratory yet, and for good reason. The month began with a presidential proclamation stating, "All people deserve to live with dignity and respect, free from fear and violence, and protected against discrimination, regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation."

On June 26, the U.S. Supreme Court's 5-4 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges legalized same-sex unions across the country and provided the perfect backdrop for New York Pride two days later.

Photo: Daniel Bendjy/iStock

Images of Pride marches mirror the post-Stonewall queer experience from protests born from police violence through the AIDS epidemic and the long road to marriage equality to today's fight for the rights of trans people. The marches have remained a source of strength, hope, and positivity in the face of adversity and demonstrated to the world the resilience of a community that has been making its voices heard for 50 years.

Photo: Kena Betancur/Getty Images