112 seconds.

Ellen Trawick’s 32-year-old son, Kawaski, was killed by New York Police Department officers in less than two minutes on April 14, 2019. After more than a year and a half, the Bronx District Attorney investigated and cleared the officers of criminal charges. There was a hallway security camera and a body camera recording the event. However, yet another month would pass before the NYPD released the video.

Six months later, a civilian review board recommended firing officers involved in the shooting. Officer Brendan Thompson and his partner, Herbert Davis, entered Kawaski’s Bronx apartment improperly, the police oversight agency found. The fatal interaction between NYPD officers and the person they were supposed to protect unraveled within 112 seconds, but the disciplinary process has taken nearly two more years.

Finally, four years after her son’s death, Ellen may achieve what she desires: the termination of the police officers who killed her son. The police officers involved in her son’s death appeared before an administrative judge in April. Hearings continued this month and a decision should be announced soon.

Much of the information Ellen has received is based on the NYPD’s claim that her son was experiencing a mental health crisis. While Kawaski had mental health struggles, he had no history of mental health emergencies, and given the NYPD’s training in de-escalation, if the officers assumed Kawaski was in crisis, they should have treated him accordingly, she says.

Ellen knows what happened to her son, almost as if she was there. A video clip of the gay Georgia-raised fitness enthusiast who moved to New York City a year earlier to become a dancer is etched in her memory. As she talks about what happened, she’s brought back to that day. (The video of the Kawaski's killing, via ProPublica, can be viewed here — the clip is disturbing, viewer discretion is advised.)

Kawaski walked through the hallway of his Bronx supportive living apartment building in his underwear, a long sleeveless jacket, and cowboy boots. In his hands were a long walking stick and a serrated bread knife. As he reached the door, he checked his pockets for his keys. After failing to find them, he walked away.

Kawaski returned to his door 15 minutes later with four firefighters; he had called them to report a fire. Using a Halligan bar, firefighters pried open the door. After ensuring no fire — Kawaski left the stove on before getting locked out — the firefighters turned and left, and Kawaski waved to them.

There was no need for further involvement at this point.

In the lobby, two NYPD officers chatted with building staff before leisurely making their way to the fourth floor. They learned that Kawaski had been acting oddly and may be on drugs.

Brandon Thompson, a white police officer with three years of experience, and Herbert Davis, a Black veteran police officer with 16 years on the force, knocked on Kawaski’s door and pushed a small opening, revealing a slight gap. The officers put on gloves, dislodged the security chain, and opened the door.

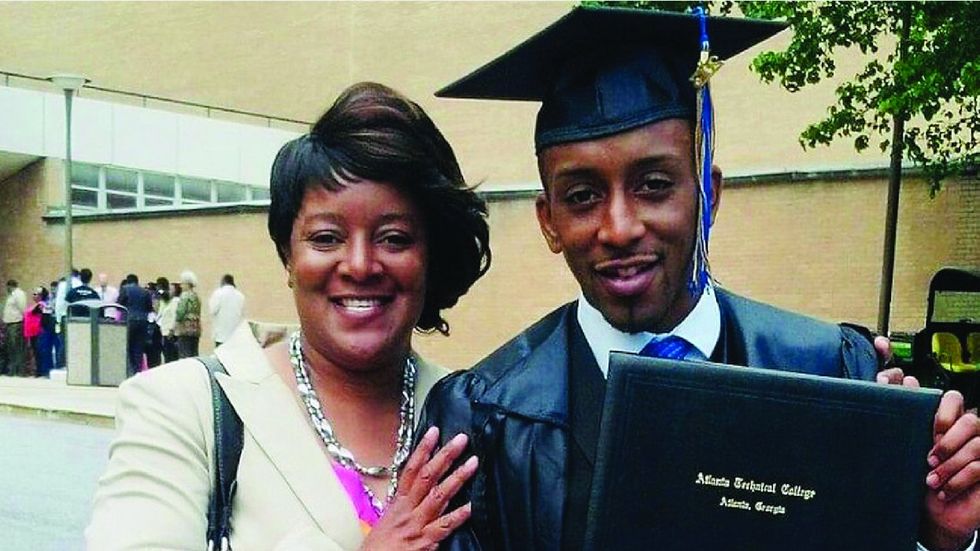

Courtesy Trawick family

Courtesy Trawick family

Startled, Kawaski, still cooking, was holding a bread knife and a stick in his hands.

“Why are you in my home?” he asked.

Since the officers entered his home without permission and didn’t explain their presence, he was agitated. Although presented with an opportunity to sympathize with Kawaski, the officers aggressively pointed a Taser at him, with a red dot moving around his body. When Kawaski asked them why they were at his door, they ignored him.

Davis warned his less-experienced partner against using force. Then, putting his Taser away, Davis said, “We ain’t gonna tase him.” When asked by the officers why he had a knife, Kawaski explained that he’s been cooking, but he didn’t put it down after being asked several times. But with his home breached and weapons drawn at him, Kawaski was clearly confused, angry, and frightened.

With the Taser light finally off of Kawaski, Thompson switched to a gun, which he pointed at the distressed man.

Less than a minute passed as Kawaski conversed with the officers. “I just called the Fire Department because I was locked out of my home,” he told them. “Why did you just kick in my door?” he asked. Davis told Kawaski he knocked on the door and that it was open (in reality, the chain was secured and Davis reached inside and unhooked it).

Officers continued to insist he drop the knife. When Davis realized he had forgotten his body cam, he said, “I don’t have my camera on, so be careful.”

Thompson repeatedly commanded, “Drop. The. Knife.”

With the Taser in his left hand and the gun in his right, Thompson aimed at Kawaski. In response, Kawaski began rambling incoherently and Thompson squeezed the trigger, sending tens of thousands of volts of electricity through his body; Kawaski screamed and fell to the ground.

Once Thompson dropped his Taser on the ground, Davis and Thompson fully entered the apartment.

Before the officers could handcuff Kawaski, he rose and yelled, “Get away!” Then, holding the knife, he leaped backward away from the officers, screaming, “Get out, bitch!”

As Thompson pointed his gun at Kawaski, Davis tried to stop him a third time. He briefly pushed the gun down and said to Thompson, “No, no — don’t, don’t, don’t, don’t, don’t.”

Kawaski yelled, “I’m gonna kill you all! Get out!”

“Brandon Thompson shot him,” Ellen says. “And I can hear him asking, crying, saying, ‘Why did you shoot me? Why did you shoot me?’ And then I saw Herbert Davis close the door.”

Kawaski had fallen to the ground, killed nearly instantly after being shot through the heart, according to a report from the Bronx district attorney.

People experiencing crisis can present unpredictable and dangerous situations to police, “as the NYPD has long known,” says Loyda Colon, executive director of the Justice Committee, which holds law enforcement officials accountable. “Officers who arrived at Trawick’s door that night had both completed the latest departmental training for dealing with such situations. But clearly, as we saw in Kawaski’s case, [crisis intervention] training does not make them experts at handling these situations.”

At a minimum, much more extensive mental health education is needed—years of it—for officers, Colon says, rather than just the few hours of training currently required. Ideally, when someone is in crisis, trained professionals should respond, Colon adds. New York police have killed at least 18 people suffering mental health crises since their current de-escalation procedures went into effect in 2015.

“It’s absurd to continue to have the NYPD playing this role and for Mayor Eric Adams to try to expand it,” they add.

According to Ellen, if her son was indeed in distress, officers failed to take responsibility for his well-being.

“My family and I want these two officers to be fired,” Ellen says. “They should not be able to receive any benefits or anything that comes with their work. They should be fired. They should not be allowed to continue to work as police officers anywhere.”

Colon criticizes what they call “delays and cover-ups” in investigating Kawaski’s killing by Thompson and Davis and the “obstructionist behavior of the NYPD under New York City Mayor Eric Adams.”

Colon and Ellen are urging Adams to intervene and pressure NYPD Commissioner Keechant L. Sewell to hold the officers accountable for their actions.

“There’s very little visibility nationally of the impact of police violence on queer and trans people,” Colon says. “But it’s been part of our community’s history forever. And in spite of cosmetic reforms, NYPD still targets queer and trans people of color with baseless arrests and violence. Yet, Mayor Adams continues to act like an LGBTQ champion in the national press while locally in New York City, he’s appointed people with long histories of homophobia and anti-abortion stances into the top posts of his administration.”

A spokesperson for the mayor says that he is committed to the well-being of all New York City residents.

Courtesy Trawick family

Courtesy Trawick family

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella