Above: Lesbians and gays march up Fifth Avenue in 1993

New York City Mayor David Dinkins passed on an offer to lead the St. Patrick's Day Parade in 1991, deciding rather to march with LGBT Irish people, who had initially been denied entry into the parade until Dinkins intervened. Nonetheless, that group was booed for the entire 40 blocks. People on the sidelines hurled epithets and even beer cans at them, which Dinkins dodged with an umbrella. Two men were later arrested for throwing the cans.

"Every time I hear someone boo, it strengthens my resolve that it was the right thing to do," Dinkins told the Associated Press.

New York's Cardinal John O'Connor, who was known for being antigay, said he asked Catholics not to be violent during the march.

"That's not what we're about," he said, according toThe New York Times. "We don't return disrespect with disrespect."

Meanwhile, Gov. Mario Cuomo also opted not to march at the front of the line, instead joining a group of children in wheelchairs who were initially denied space to march.

The following year, Dinkins, Cuomo, and other political colleagues boycotted the 1992 parade because of the antigay exclusion. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, the "oldest and largest Roman Catholic organization in the United States," argued in federal court that it had the right to bar LGBT participants from the parade. The argument held up in court, after months of legal debate.

As a result, about 400 protesters lined the streets to counter the 150,000-strong throngs of Irish marchers. One protester held a sign reading, "My Irish eyes are bright and gay, but they are not smiling." Another sign read, "Gay, Irish and Proud," according to the Los Angeles Times.

Video from that parade:

St Patrick's Day Parade, NYC 1991-1992 from Lisa Guido on Vimeo.

Above: New York City Police carry a protester to a police truck after she was arrested during the 1997 parade

In his last years as mayor, Dinkins attempted to rescind power from the Ancient Order of Hibernians, but was unsuccessful in doing so. When Republican mayoral contender Rudy Giuliani ran for office in 1993, he decided to march in the parade, and 228 LGBT protesters were arrested. When Giuliani took office in 1994, he continued the tradition of the mayor participating in the parade, despite the gay ban.

The Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization made continuous legal challenges to the ban, even reaching the U.S. Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled in 1995 that parade organizers had a right to the freedom of speech, since parades are a form of expression.

As LGBT people continued to be shut out of the parade, protests only became nearly as predictable as the parade itself. In 1997 about three dozen demonstrators with ILGO were arrested as the parade held a moment of silence to memorialize the millions who died in Ireland due to the potato famine 150 years prior.

The following year, even the New York Gay Officers Action League, a police group, was excluded from the parade.

In 2000, outgoing first lady and New York challenger for the U.S. Senate Hillary Clinton participated in the parade after months of debate. The following year, however, Senator Clinton marched in the Syracuse St. Patrick's Day Parade, where LGBT participants were welcome.

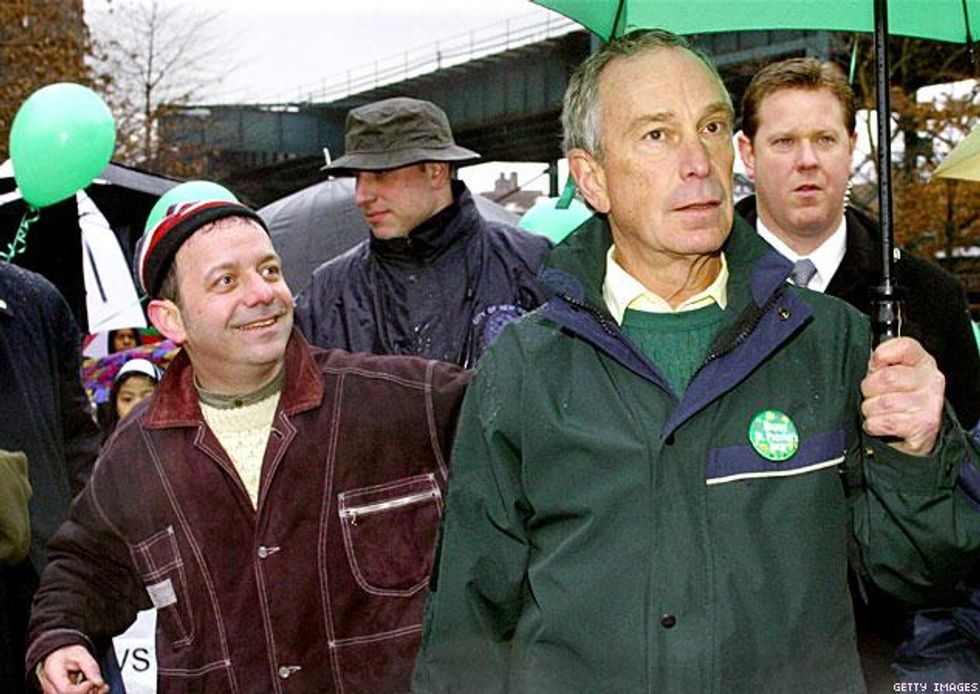

Above: Brendan Fay (left) walks with Mayor Bloomberg in the LGBT-inclusive parade March 2, 2003 in Queens.

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg took office in 2003, he typically participated both in the St. Patrick's for All Parade, held in Queens, in early March, as well as the big parade held on Fifth Avenue. Bloomberg, however, has been on the record saying the gay ban was a "misguided policy" that he tried to urge organizers to change. The parade in Queens, launched in 1999 by Brendan Fay, continues to this day.

Meanwhile, Boston, which has its own traditional parade, has excluded LGBT marchers since 1992, as it is also organized by a private organization, the Allied War Veterans Council. In addition to serving its large Irish community, Boston's St. Patrick's Day Parade also commemorates the day the British were run out of the city in 1776. The parade focuses largely on veterans, which made it even more difficult for LGBT people to participate in the parade, due to the military's ban on openly gay service members. The Supreme Court ruled in 1995, in Hurley v. Irish American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, that gays could be excluded by organizers because it is a private event, and parades are a form of expression.

Because of this, the city also has alternative festivities, known as the St. Patrick's Peace Parade, organized by the pro-LGBT Veterans for Peace, which was specifically created to "end the last vestige of institutionalized exclusion, prejudice, bigotry, and homophobia and make this parade inclusive and welcoming to all and bring the message of peace to South Boston on St. Patrick's Day," Autostraddle reports.

Video from this year's St. Patrick's for All Parade:

This year in Boston, talks between the organizers of the St. Patrick's Day Parade in South Boston and MassEquality broke down over whether the parade would include openly LGBT veterans. Organizers for the parade initially said LGBT veterans would be allowed to march in the annual tradition, after years of LGBT participants being shut out due to a "no sexual orientation rule." However, the question of whether participants could display signs or shirts that identified them as LGBT was a major sticking point.

Then, days later, officials with the South Boston Allied War Veterans Council, which organizes the parade, said they were misled by LGBT Veterans of Equality, which is a subgroup of MassEquality. Parade organizers claimed that MassEquality misrepresented the number of actual LGBT veterans participating, so they could not take part in the event.

Kara Coredini of MassEquality said her organization had in fact worked with numerous veterans to end the military's ban on openly gay service members, "and those same veterans would have been proud to represent the end of the parade's 'don't ask, don't tell' policy."

"We know from experience that change comes through conversation and dialogue," Coredini said. "We were encouraged to have an historic opportunity to meet face-to-face with parade organizers to discuss a contingent involving LGBT veterans, and we did so with open hearts and open minds."

New York might have the largest St. Patrick's Day Parade in the world, but in Dublin, Ireland, the parade actually has been quite inclusive to LGBT participants. Richard Conway, an Irish transplant to New York, wrote in 2012 that his new city practiced "outmoded" bigotry. Modern Ireland, he says, is accepting of LGBT people, and most Irish people -- as in, people who live Ireland -- agree that same-sex marriage should be legal. Because of that, Dublin's parade has regularly included gay-themed floats while organizers of New York's parade say there's a "don't ask, don't tell" policy; gays can participate as long as they don't signal their sexual orientation to onlookers.

So, years later, the protests in New York continue. And to continue the tradition of Democratic mayors who don't support the antigay policies of the parade, new mayor Bill de Blasio said he would not participate in the parade, a practice he has followed, even as a public advocate for the city.

This Monday, Irish Queers has plans for a demonstration, as it is becoming tradition. According to the group, "Numerous elected officials from Ireland and New York are refusing to march in the parade because it is such an embarrassment. But thousands of uniformed NYPD cops and firefighters still march in their uniforms which sends the wrong message to GLBTQ New Yorkers, especially those who are already at risk of being targeted for harassment by the police."