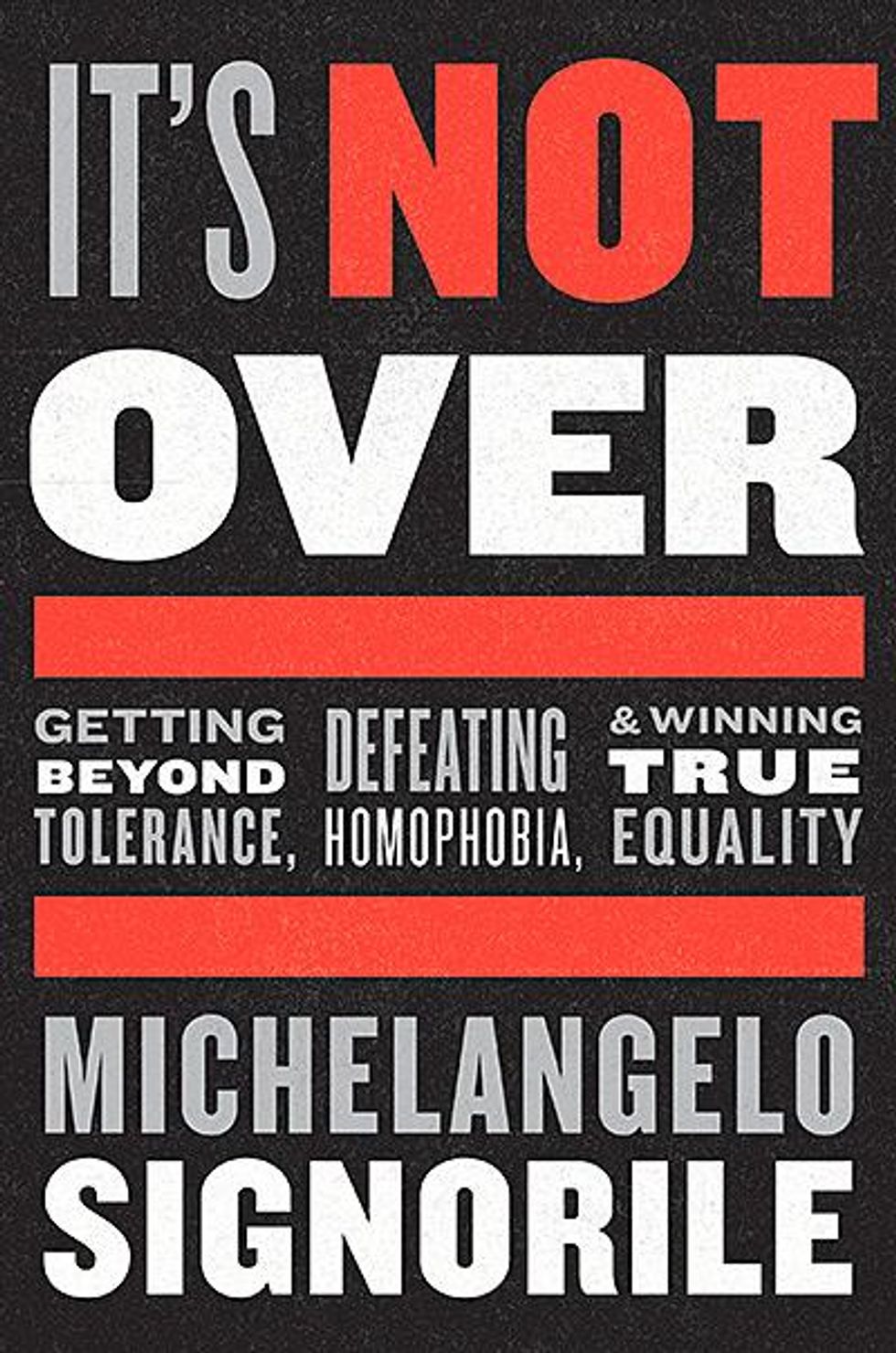

Ever the rabble-rouser, Michelangelo Signorile, author of the new book It's Not Over, offers sobering lessons for the future of LGBT rights.

April 07 2015 4:30 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

deliciousdiane

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Ever the rabble-rouser, Michelangelo Signorile, author of the new book It's Not Over, offers sobering lessons for the future of LGBT rights.

I'm from a small town in rural Idaho and when I was 12, I started hanging around the office of the local weekly newspaper, the Independent Enterprise. (Or as my aunt Luanne still lovingly calls it, the "Spitwad.") Soon the editor gave me a school beat column, and a few years later, I became editor of our high school newspaper, which we produced at the office of the Enterprise's bigger sister paper, The Daily Argus, published across the river in Oregon.

In high school, I'd attend my English and journalism classes in the morning, and then I'd often skip the rest of the day and go work on newspaper stuff. Most of the time, my teachers excused me. We didn't have computer, Google, or even the Internet. I learned to type on a manual typewriter (not even an electric one) and I produced the newspaper on something popular in the 1980s called a video display terminal.

Things moved so swimmingly for me in the publishing world then -- at 18, I was already the Argus's lifestyle editor pro tem -- that I fancied myself the next Ben Bradlee meets Jessica Savitch meets Helen Gurley Brown. By the time I left New York for Los Angeles at 20, after hopping around jobs at magazine, book, and multimedia publishers, a confluence of factors changed the course of my career -- and my life -- and none were more pivotal than Michelangelo Signorile.

I learned of Signorile, author of the new book It's Not Over: Getting Beyond Tolerance, Defeating Homophobia, and Winning True Equality (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), when he too was a young queer radical. Eight years older than me, he was a pivotal part of ACT UP in New York as I was a member in Los Angeles; he cofounded the original direct-action group, Queer Nation, while I later participated in Los Angeles and opened up a chapter in Boise, Idaho.

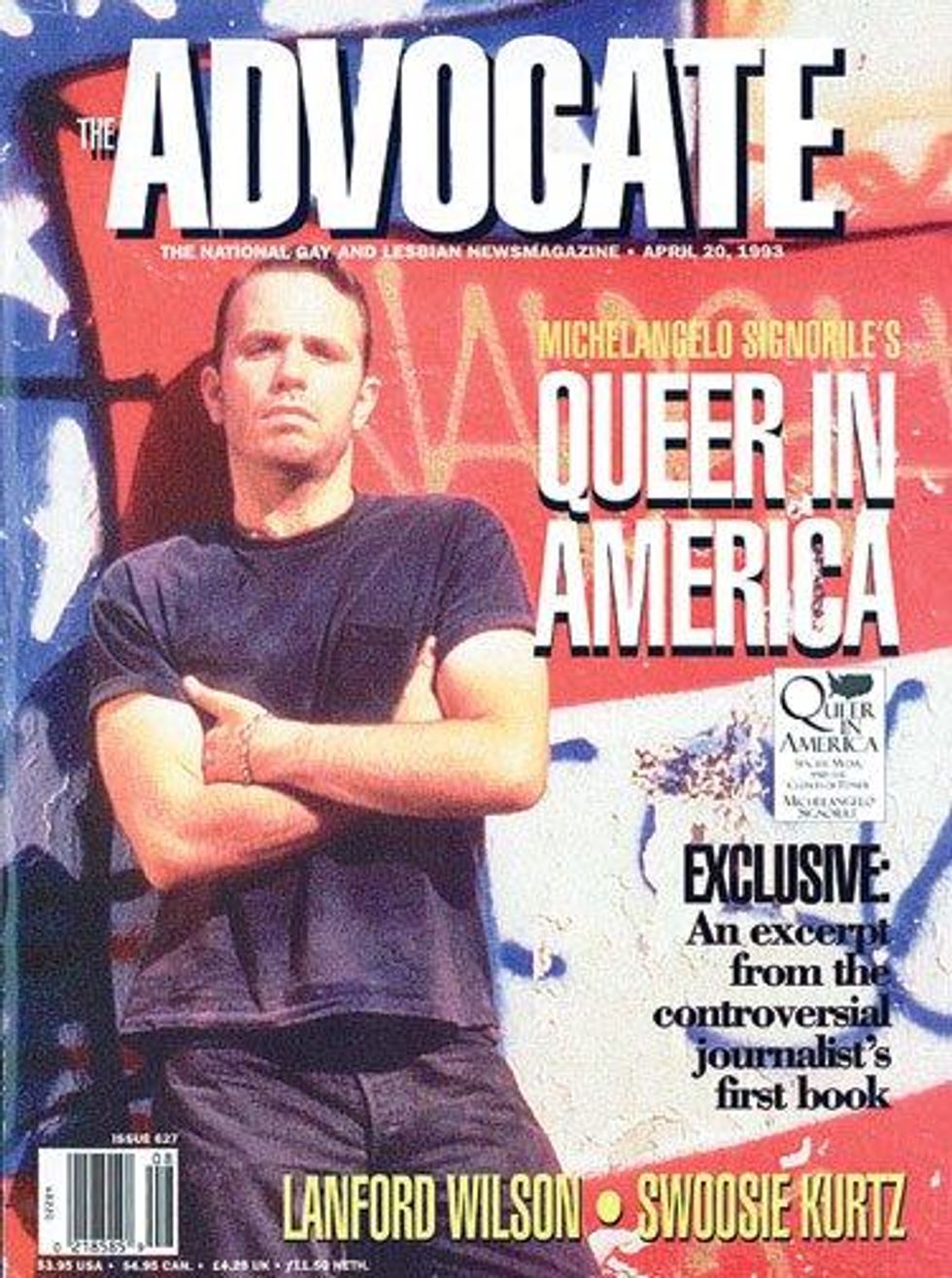

OutWeek was a bold lesson in advocacy journalism long before there was acceptance of the phrase. It was confrontational and raw and smartly aggressive; and the thing that Signorile did well, besides eviscerating the Establishment and closeted antigay politicians, was demand equalization in reporting on both straight and LGB celebrities, refusing to closet people who seemed to be living openly gay (or bi or lesbian) lives, even though mainstream media had always done so.

It was a rule in Hollywood at one point that people like Rosie O'Donnell, Ellen DeGeneres, David Geffen, and Jodie Foster could live out gay lives among their friends, family, and industry insiders, but they didn't need to admit it to the rest of America. The media all knew who was or wasn't queer. (Though gay cross-dressers were sometimes "outed" in LGBT media then, trans people were rarely reported on unless they were actively anti-LGBT; their "outing" has largely been frowned upon since.) (Though OutWeek closed after only two years, it had significant impact on LGBT media, pioneering a new queer journalism, and forcing The Advocate to rebrand as a "gay and lesbian" magazine with more focus on politics and the AIDS crisis.

Like OutWeek, Signorile has never tried to make queer or trans people look presentable, the "model gays" so many of us felt compelled to be in order to make our families, schools, and churches comfortable with us. The "we're just like you, let's blend in" ethos was actually described first by author Kenji Yoshino, who authored the aptly titled book Covering. Signorile tells me why he references the ahead-of-its-time book frequently in It's Not Over: because Yoshino "makes the case for why, trying to give the public some space, pulling back, fitting in, after we've made a few wins, is a trap. It contains us and allows for the backlash. We need instead to continue to focus on our difference, our uniqueness, and make people accept who are, as we are, rather than trying to 'cover' and fit in. I do think there's this impulse among gay leaders to do that, because it can lead to short-term wins -- and help fund-raise -- but in the long-term it's self-defeating." (Yoshino, it should be noted, has his own shrewd new book out this year: Speak Now: Marriage Equality on Trial.)

Signorile calls this "victory blindness." He's worried that people are "being consumed by victories and not seeing the treacherous path ahead. Too many people have succumbed to it, and it's happened to other groups in history fighting for their rights. People need to realize that the fight will probably not be won in any of our lifetimes and the setbacks will be many. We need, urgently, to zoom out of this moment and see that we live within a culture that has very deep beliefs -- many but not all of them religion-based -- about race, gender, and sexual orientation."

We have made great strides for some parts of the LGBT community. At the same time, all around us other movements have seen gains "rolled back in ways that would have seemed unimaginable 40 years ago," he writes.

"The great part is that we also live in a democratic system in which people can organize and fight hard and change things and pass laws and go to court -- and we have," Signorile tells me. "But that doesn't change the culture as much as we like to think. We see that African Americans, all these years later, are seeing both setbacks, the Voting Rights Act stripped, affirmative action attacked, and continued racist incidents, including police violence. People say, well it's different -- and yes, all these groups and movements are very different -- because LGBT are within every family, unlike the issue for racial groups. But women are also in every family, and they have another big advantage: They happen to be the majority. And still, we've seen the setbacks" on issues like contraception, abortion, and economic equality.

(BOOK EXCERPT: The 'Inappropriate Behavior' Double Standard)

I'm with Signorile. I always have been. If there was a cult of Mike, I'd be there, old copies of OutWeek and Girlfriends -- the queer women's magazine I cofounded the year his seminal book came out -- in one hand, my laptop in the other. The thing is, he's pretty prescient about this stuff and has been for decades now. In 1993 he tackled the hypocrisy of not allowing gays in the military (after the Pentagon's Pete Williams was outed by The Advocate) and the media's culpability in the covering that goes on in Hollywood. He wrote, "There is no 'right' to the closet. If you are in it, it is not by your choice. You were forced into it as a child, and you are being held captive by a hypocritical, homophobic society. Now is the time to plan your escape."

The author, who today hosts SiriusXM Radio's The Michelangelo Signorile Show and serves as editor at large for The Huffington Post's Gay Voices vertical, has always understood that culture is enormously powerful, that "we have no idea how things will shift in three years, five years, 10 years, or 40 years. This country has experienced enormous religious revivals that attempted to curb rights in the name of religion at various points over the past 225 years. Then they wane, often with the help of rights activists who fight back, only to revive again. What happened in the '80s -- the Christian evangelical revival, a backlash to the '60s and the sexual revolution and women's liberation -- was nothing unique."

He argues that there's always an opportunity to foment the backlash because the vast majority of people are basically always resistant to change. "So when you get things done -- like get full marriage equality -- that's actually the most dangerous time," he says. "The public, even as it supports one particular stride forward, is vulnerable to the messaging from the other side that things are changing too much, too fast. The enemies of equality know they can take advantage of that and find an issue that many in the public are uncomfortable about," like so-called partial-birth abortion, affirmative action, or, now, bakeries being forced to create wedding cakes for same-sex couples; and then, he says, they exploit it.

Our only choice, as far as Mike sees (and I agree), is going full force, "full throttle rather than pulling back and thinking we've won and being 'magnanimous,' which there is an impulse for many to do.... Even among our own, there's that same resistance to change and there's often even a sympathizing with the public on the pressure to change." While we've pushed the American public to make this change, pushing for LGBT rights, many queers will think this is a "lot" for their friends and family to go through, thinking, he says, "maybe we need to pull back. This is the essence of victory blindness -- it gives ammunition to the enemies."

Signorile insists that we stop compromising on incremental change, demand big advances, stop covering for ourselves and others, stop letting the media control the message, and demand nothing less than full equality.

Now the main question is, are LGBT groups like HRC ready to hear this? Are you? Or come 2016 will we have a lot of people too busy picking out wedding china to recognize that the fight has only just begun?