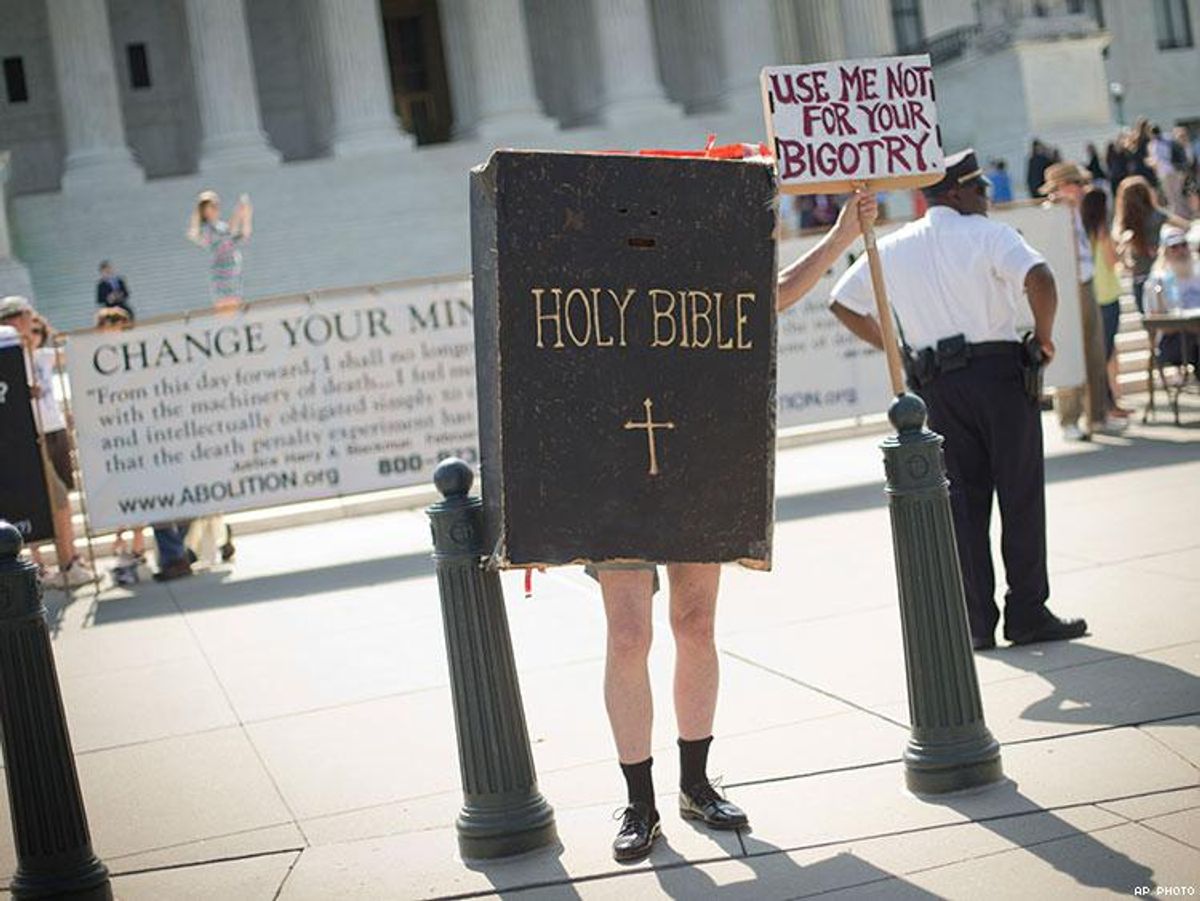

Religious freedom is all the rage these days. To hear it told by conservative activists, the constitutional promise of each citizen's free exercise of religion is under attack like no other time in U.S. history. Surely, such an urgent question is headed for the Supreme Court, right?

Maybe not so fast. Several out attorneys who have spent decades fighting for LGBT civil rights tell The Advocate that we may be settling in for another long, drawn-out battle that challenges discriminatory laws state by state, clause by clause.

"The question is, should religious freedom be used as a sword to create a license to discriminate, to undermine civil rights advances that have already been made?" That's how Evan Wolfson frames the decision judges will face. He's the founder of Freedom to Marry and a key architect of the legal and cultural strategy that won marriage equality.

It's no secret that the recent uptick in legislation aimed at protecting "religious freedom" is in part a backlash to the same-sex marriage victory and the other historic gains achieved in LGBT equality over the past few years. In some ways, the onslaught of discriminatory bills was predictable.

"The abuse of religious exemptions as a tactic for undermining civil rights advances is a classic pattern of civil rights progress in America," notes Wolfson. "In the '50s and the '60s and the '70s and the '80s, whether it was with racial minorities or women or other steps forward -- including now gay and transgender people -- when the opponents of civil rights progress fail to stop an advance, they then try to circumvent it."

In the case of LGBT equality, numerous state legislatures joined the circumvention effort, sending activists into action on the legal or lobbying fronts. Over the past two years, the right-wing's attacks have largely taken the form of so-called Religious Freedom Restoration Acts. These laws claim citizens deserve the freedom to cite their religious beliefs to deny service to those who don't agree with them, because otherwise those same individuals must suffocate their faith to abide by nondiscrimination laws.

The permutations of Religious Freedom Restoration Acts are numerous, but they do follow some basic trends. The federal RFRA, passed in 1993 under President Bill Clinton, was initially created to protect members of religious minorities. Congress created the law after the Supreme Court rejected a First Amendment complaint brought by two Native Americans who had been fired from their jobs and denied unemployment benefits because they used peyote, an illegal drug, in their religious ceremonies, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. When the federal RFRA was first enacted, it enjoyed the support of civil rights organizations such as the ACLU, and to this day, the federal law makes no reference to sexual orientation or gender identity. But last year, amid the nationwide controversy over Indiana's RFRA, the ACLU formally rescinded its support for the federal law, expressing concern over the increasing breadth with which it had been interpreted.

In Indiana last year, a Republican governor signed a sweeping version of the law during a secret ceremony, with detractors saying it gave Hoosiers a "right to discriminate" against LGBT people. It was met with such severe and widespread backlash that lawmakers scrambled to create a hasty "fix."

But if Indiana was outrageous, all the more insidious are a novel category of legislation that are like a mutant cousin of the federal RFRA. Broadly positioned as First Amendment Defense Acts, these laws prevent state and local governments from taking any punitive action against individuals, organizations, and businesses that espouse a particular set of beliefs. Although it's not always the case, these bills single out a select few parochial perspectives for special treatment.

That's clearly the case in Mississippi, where the latest FADA-style bill, signed into law by Republican Gov. Phil Bryant earlier this year, specifically lists three "sincerely held religious beliefs" that cannot be subjected to government intervention. Those beliefs, as stated in the text of the law, include that "marriage is or should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman; sexual relations are properly reserved to such a marriage, and; male (man) or female (woman) refer to an individual's immutable biological sex as objectively determined by anatomy and genetics at time of birth."

The Mississippi law, formally titled the Protecting Freedom of Conscience From Government Discrimination Act but better known as House Bill 1523, prohibits "discriminatory action" against religious organizations, individuals, or even employees of the state, including elected public officials like county clerks or registers of deeds, who are responsible for issuing marriage licenses. The law takes effect July 1.

Allowing public officials to refuse service to law-abiding citizens based on a particular religious belief is what attorney Roberta Kaplan calls one of the most "pernicious" sections of the law, though she's quick to note there are numerous legal issues the new law raises. That's why she and her legal team have asked a federal judge to reopen the case that Kaplan filed back in 2014 targeting the state's ban on same-sex marriage, before the Supreme Court declared all such laws unconstitutional in its Obergefell v. Hodges decision last June.

The Mississippi law, Kaplan says, "isolates out three particular religious beliefs, that it says somehow deserve preeminence or precedence over any other religious belief. ... Those are the only three religious beliefs privileged under the statute."

So even though the law purports to make accommodations for "sincerely held religious beliefs and moral convictions," it actually only makes those accommodations for a very particular set of beliefs and moral convictions.

"That's one of the things that, frankly, makes this statute so unconstitutional," Kaplan adds.

"It has to be all or nothing," Kaplan concludes. "It has to be equal. Saying that you're willing to marry straight people but not gay people is like saying black kids get to swim in the creek and the white kids get to swim in the town swimming pool."

Kaplan is no stranger to arguing for LGBT equality at the Supreme Court, as she represented lesbian widow Edie Windsor in her landmark 2013 case that effectively struck down the federal Defense of Marriage Act. Kaplan was also the lead attorney on the federal lawsuit that invalidated Mississippi's ban on same-sex couples adopting children. When that decision was handed down in March, Mississippi was the last state in the U.S. to still have that strain of antigay discrimination on the books.

But there is hope on the horizon. The sweeping nature of these FADA bills, which specifically elevate a particular set of religious beliefs, puts them on shaky constitutional ground, the attorneys interviewed for this piece agreed.

According to the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Romer v. Evans in 1996, laws that single out a particular group for discriminatory treatment must demonstrate that the exclusion somehow advances a "legitimate governmental interest." In that case, it was Colorado voters who had approved a constitutional amendment that sought to bar gay, lesbian, and bisexual residents from obtaining any nondiscrimination protections based on their sexual orientation.

"A bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest," Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the majority in the 5-4 decision in Romer. The decision itself was historic, as it was the first pro-LGBT ruling handed down by the nation's high court, and it signaled a turning point in the legal battle for basic LGBT rights.

Perhaps proving they've learned from Romer, though, anti-LGBT lawmakers these days are less explicit about which groups they're targeting. The trend in RFRA legislation is to never include any mention of the words "gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender," or even "sexual orientation or gender identity."

So while many of the FADAs come out and say it plainly, RFRAs are subtle. That can make a differnce in the courtroom and in politics. The pointed language expressly targeting LGBT people was a key factor in defeating Georgia's FADA, which was passed by the state's legislature earlier this year but then vetoed by Republican Gov. Nathan Deal, who said anti-LGBT discrimination was not a "Christian" value.

"We have very strong reasons to believe, including some legislators' very open comments [and] the timing of the bills ... that they are intended at least in part to be anti-LGBT," says Sara Warbelow, legal director at the Human Rights Campaign, of recently passed RFRAs. "But the FADAs make no bones about it. They just plainly say that if you believe that marriage is between one man and one woman and that sex needs to occur within that marriage, that the state can't take any action against you."

Characterizing the Mississippi law as "bizarrely broad and narrow simultaneously," Warbelow explains that HB 1523 is clear about who it intends to disenfranchise, and which beliefs it protects from "government discrimination." The text of the law goes to great lengths to define what kind of wedding-related services can be denied to same-sex couples if the business owner ascribes to one of the privileged beliefs about who should be able to marry, but it also opens the door to much more dire anti-LGBT discrimination.

"One of the things that I find particularly disturbing about the Mississippi [law] is that it allows foster and adoptive parents to go unsanctioned by the government if they treat their foster or adoptive children according to those beliefs," says Warbelow.

She posits a hypothetical where an LGBT youth in the foster care system -- like a disproportionate number of queer youth are -- is placed in an adoptive home or foster home where the family's religion says that LGBT people are sinful, or worse, can be changed. If those Mississippi parents subject a young person in their care to so-called conversion therapy -- which is not only wholly ineffective and discredited but often also inflicts real damage on LGBT people -- a social worker overseeing the case would have no legal right to remove the child from that home, provided the parents claimed they were acting in accordance with their sincerely held religious beliefs.

Ultimately, though, that terrifying provision could be what takes down Mississippi's latest attempt at state-sanctioned hate.

"If you pass a law that effectively could allow abuse toward a child, that's clearly a violation of the child's constitutional rights," Warbelow says. She goes on to explain that she believes the Mississippi law could also be challenged as "impermissible viewpoint discrimination, bare animus toward LGBT people, and unequal protection of the laws for LGBT youth."

But even if Warbelow and Kaplan's strategies are successful in dismantling Mississippi's latest attempt to legalize anti-LGBT discrimination, there remain an untold number of "religious liberty" bills waiting in the wings.

Some of the modern iterations of these religious freedom laws hew closely to the federal RFRA, which is comparatively narrow in scope, and therefore generally considered constitutional. But the new wave of bills claiming to protect religious freedom have a broader and, advocates say, more sinister motive.

"It's not just about LGBT people," Warbelow explain. "It's about so much more. That's an element of why these states are trying to pass [religious freedom laws], but it's also very much about birth control. It's very much about restrictions around abortion or even having to talk about abortion. It's about creating a system in which the religious majority gets to live out their faith regardless of whom it hurts."

The challenge, these attorneys agreed, is that litigation is designed to address one particular issue or constitutional question at a time. With laws that enable such widespread, multifaceted discrimination, each of those discriminatory provisions will have to be struck down individually, in every state where such a law exists. And even if this Herculean effort is successful, there's nothing stopping determined anti-LGBT lawmakers from reintroducing slightly amended versions of bills that may have already been struck down in court.

"I actually think the American people are fundamentally with us, on understanding how the effort to use religion as a sword needs to be rejected in this [election] cycle," says Wolfson. "It's a multiple set of engagements we need to do, but the big lesson of the marriage work is: Get ahead of it. Have an affirmative strategy. Don't just be reacting."

Warbelow agrees and stresses that the problem isn't with the concept of religious liberty.

"There's still a real need for protections for religious minorities," says Warbelow. "It's just that the [federal RFRA] law has been misused by the courts."

She points to the Do No Harm Act, a piece of legislation introduced by two Democrats last month in the U.S. House of Representatives that looks to revise the federal RFRA to clarify that it cannot be used to discriminate against members of any minority class, be they religious minorities, LGBT people, and/or women. The bill, Warbelow says, seeks to "restore RFRA to its original intent."

"We need to reenvision what it means to protect religious liberties," Warbelow says, "without creating a system in which it's a free-for-all for discrimination."