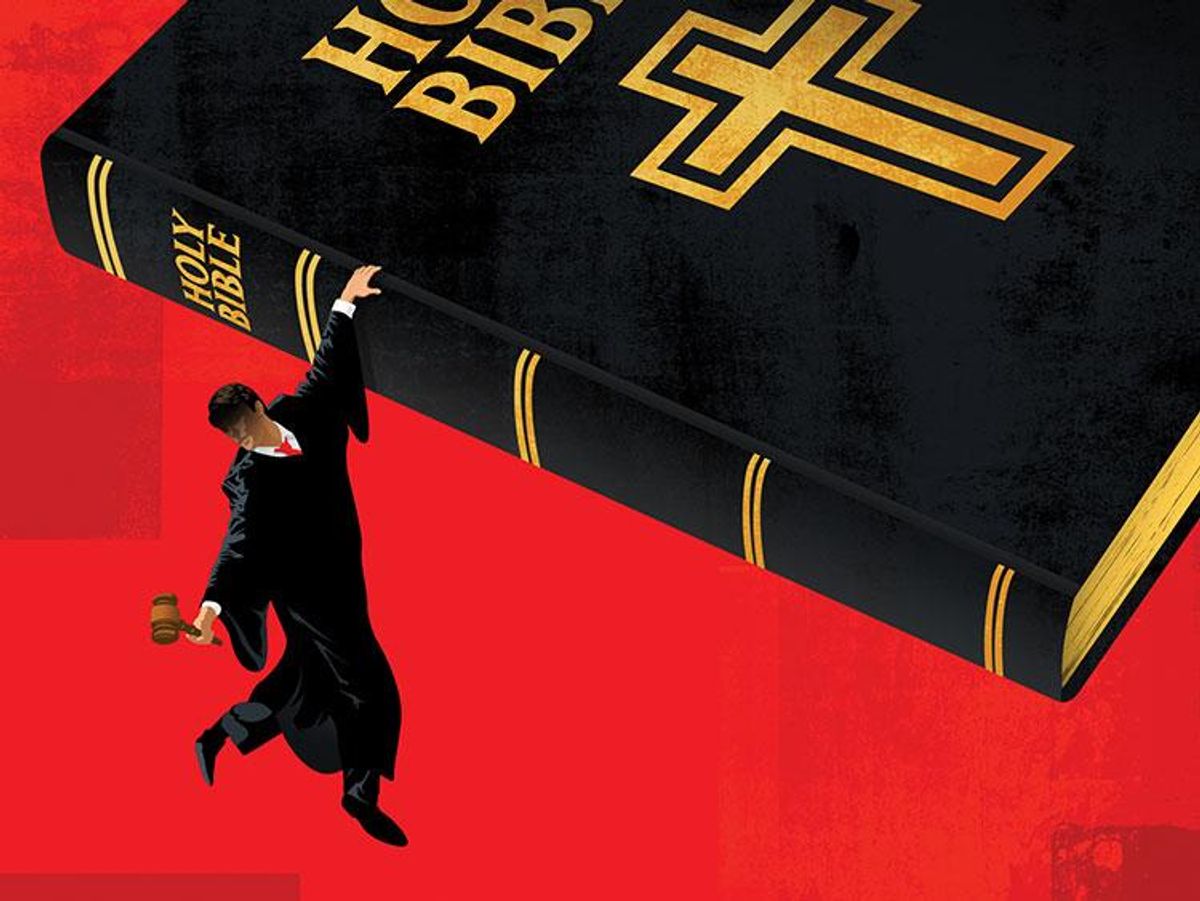

Illustration by Taylor Callery.

When the Supreme Court affirmed same-sex couples' constitutional right to marry in June 2015 in Obergefell v. Hodges, Justice Samuel Alito warned darkly that the decision would diminish "the rule of law." That phrase -- "the rule of law" -- gets thrown around a lot in civil rights litigation, mostly by judges implying that their colleagues are power-mad tyrants. But Alito's deployment of the line was especially notable, because in the following months, Southern state court judges would cite his ominous premonition as a justification to ignore the law -- in favor of good old-fashioned biblical authority.

In one sense, the legal battle for marriage equality was always a battle to define the rule of law. On one side sat gay people and their allies, who argued that the intertwined constitutional commands of "liberty" and "equal protection" required states to let same-sex couples wed. That theory is secular, rooted in a long line of Supreme Court precedents respecting individual autonomy and equal dignity. At bottom, it held that, when citizens use the law to deprive minorities of basic rights, courts must step in to protect liberty -- sometimes at the cost of democratic self-governance. That trade-off is foundational to Brown v. Board of Education, the cornerstone of equality jurisprudence.

On the other side of the debate sat the Alitos of the world: devoutly antigay culture warriors whose religious beliefs convinced them that the Constitution's protections of fundamental liberties should never extend to gay people. Until recently, these men and women were able to present their case against marriage equality in starkly religious terms, citing their faith's opposition to same-sex intimacy. After the Supreme Court invalidated sodomy bans -- on the grounds that mere moral opprobrium can't constitute a legitimate state interest -- the culture warriors switched tacks, ranting instead about the sanctity of marriage as one man, one woman. The religious animus remained, always lingering just beneath the pretext.

Understood in this context, the campaign for constitutional marriage equality was a dispute about which law -- and which vision of the law -- should govern American life. Should we allow religious activists to enshrine their religiously motivated antigay beliefs in statutes and state constitutions? Or should we demand equal justice for gays, even when a huge portion of the American populace opposes it?

A majority of the Supreme Court, of course, chose the latter vision. In response, the conservative wing accused the court of undermining the rule of law through an "unprincipled," "freewheeling," "extravagant," "pretentious," "super-legislative" "judicial Putsch."

As the antigay justices surely understood, this kind of language has consequences: You can't say a ruling has "no basis in the Constitution," as Chief Justice John Roberts said of Obergefell, and still expect every judge to follow it.

It was no surprise, then, that Southern state court judges began to rebel against Obergefell, primarily in the deep South. Four members of the Mississippi supreme court voted to reject its validity, a clear violation of the Constitution's Supremacy Clause. One wrote that the Obergefell court had itself "acted unconstitutionally" and warned incomprehensibly about nationwide gun confiscation and forced labor camps for certain ethnic groups. Another suggested that simply recognizing Obergefell's legitimacy would violate his oath of office.

These dissents, however, were the picture of civility in comparison to the convulsions that rocked the Louisiana supreme court after Obergefell. Justice Jeannette Knoll -- a Democrat! -- wrote separately to express her views "concerning the horrific impact these five lawyers have made on the democratic rights of the American people to define marriage and the rights stemming by operation of law therefrom. It is a complete and unnecessary insult to the people of Louisiana who voted on this very issue." Not to be outdone, Justice Jefferson Hughes wrote that "the most troubling prospect of same sex marriage is the adoption by same sex partners of a young child of the same sex" -- strongly implying that same-sex couples pose a heightened risk of molesting their children. Like those four members of the Mississippi supreme court, Hughes refused to apply Obergefell because doing so would force him to "surrender" his "honest convictions."

But these polemics were really just a warm-up act for the main event: the sprawling, rambling, borderline unintelligible opinion by Roy Moore, chief justice of the Alabama supreme court. Moore rocketed to infamy in 2003 after commissioning a two-ton granite monument to the Ten Commandments for the state supreme court building. After Moore disobeyed a federal court order to remove the Decalogue, the state's judicial ethics commission removed him from office. But voters returned him to office in 2012. And after Obergefell came down, Moore happily used his position to subvert marriage equality, illegally ordering state judges to continue denying marriage licenses to same-sex couples. (Moore had previously described homosexual intimacy as "a crime against nature, an inherent evil, and an act so heinous that it defies one's ability to describe it.")

Obviously, the chief justice of the Alabama supreme court cannot overrule the Supreme Court of the United States. And for his refusal to comply with federal law, Moore has been suspended from the court and may soon be removed altogether once again. But Moore isn't backing down. In a 94-page opinion handed down last March, Moore sounds more like a Puritan preacher than a judge, peppering his sermon with biblical references and Christian theology. The Obergefell court's "redefinition" of marriage, Moore writes -- citing Genesis -- "rejects the natural order God has created." Things only get darker from there:

The Obergefell majority's false definition of marriage arises, in great part, from its false definition of liberty. Separating man from his Creator, the majority plunges the human soul into a wasteland of meaninglessness where every man defines his own anarchic reality. In that godless world nothing has meaning or consequence except as the human being desires.

Moore also accuses the Supreme Court of "elevating the 'crime against nature' into the equivalent of holy matrimony." For support, he explains that "the Bible likens marriage to the relationship between Christ and the church" (citing Ephesians) and that "the Obergefell majority creates an unnatural form of marriage whose participants delight in 'vile affections'" (citing Romans). Moore concludes that:

The great irony of the Supreme Court's embrace of the homosexual campaign to redefine marriage is that the homosexual movement has embraced marriage only for the purpose of destroying it. The ultimate goal of that movement is to drive the nation into a wasteland of sexual anarchy that consumes all moral values.

This homily may or may not be a useful theological document, but it is surely not a legal opinion in any sense of the phrase. Moore not only refuses to follow the law; he boasts that his judicial views are rooted in religion. In that sense, his outrageous invective is the inevitable result of decades' worth of thinly veiled Bible-thumping -- and an unintentional retort to Alito's grim prophecy about the rule of law. After Obergefell, the law demands equality, regardless of one's sexual identity. Judges can either follow that law or quit -- or, in Moore's case, get ousted by the grown-ups in the room. What we see in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama is the pathetic anticlimax of a hateful movement running out of steam. These judges are unable to uphold the rule of law. And whether they know it or not, they are already living in the past.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered