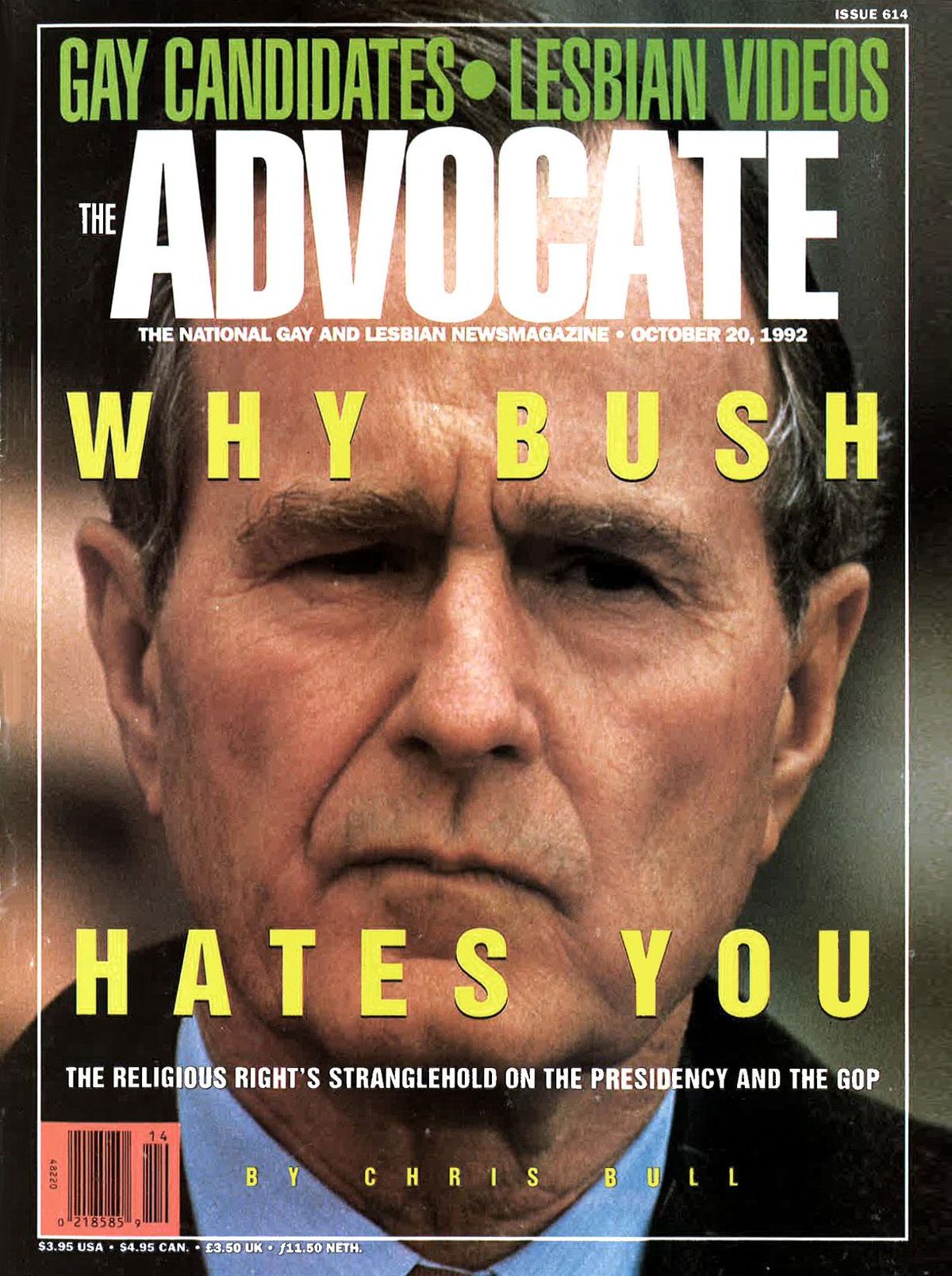

DURING HIS renomination acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, President Bush receives wild cheers from delegates when he blasts the Democratic Party's platform for omitting "three simple letters -- G-o-d."

Initiatives that would forbid legislators to outlaw antigay discrimination are placed on state ballots in Colorado and Oregon.

The California Board of Education rejects a school textbook because it calls for respect for gay and lesbian parents.

These developments, all of which occurred during the past year, and dozens of others like them across the country can all be traced to the growing political power of the religious right. Once regarded as a band of harmless crackpots, the religious right has managed to propel social issues -- especially gay rights and abortion -- to a key position on the national political agenda by sparking a fierce debate on "family values."

"These people are diehards," says Ann Stone, chairwoman of the abortion rights group Republicans for Choice. "They are very well-organized, and all they do is fight. We have to get the people to understand that unless they want a church state, they are going to have to get out there and fight back. Forget about gay rights and abortion rights in the kind of society these people have in mind."

Adds Jerry Sloan, cochairman of Project Tocsin, a Sacramento, Calif., group that monitors the right wing: "Gays and lesbians have come to terms with the fact that the religious right has effectively stalled gay and lesbian political advances in some parts of the country and actually threatens to turn back the clock in others." As a result, gay groups across the nation that would prefer to be working for positive change instead find themselves on the defensive, fighting off brush fires started by fundamentalists.

The religious right achieved its power gradually through a multifaceted strategy that targets all levels of politics -- national, state, and local. The strategy's basic components include running little-known candidates for local offices, preparing antigay ballot initiatives, organizing voter-registration campaigns, and filing legal challenges to gay rights legislation.

A key to the religious right's success has been its use of aggressive lobbying to compel the Republican Party to adopt a conservative social agenda at the expense of moderate Republicans.

"The Right has disproportionate power, not so much because it has the numbers but because it is very singleminded in its approach to politics," says David Keene, chairman of the American Conservative Union, a political group.

One need look only to the Republican National Convention in Houston last August for evidence of Keene's assertion. At the convention, Massachusetts governor William Weld, a Republican who is one of the nations most staunchly pro-gay governors, was asked by the Republican National Committee not to address gay rights in his speech to the delegates.

But there was no similar prohibition on antigay rhetoric: Gays and lesbians repeatedly were targets of attack from the podium. In a nationally televised speech, failed presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan decreed that enactment of antibias protection for gays and lesbians is "not the kind of change we can tolerate in a nation that we still call God's country." And Vice President Dan Quayle told the convention that it is wrong to treat "alternative life-styles [as] morally equivalent" to traditional ones.

Quayle acts as the Bush administration's unofficial liaison to conservatives. But on this point, he was merely parroting a position embraced two months previously by President Bush, who told The New York Times that he does not consider homosexuality to be normal. Previously, Bush had long been considered a moderate on social issues.

However, Bush and Quayle have not been entirely consistent in toeing the religious right's antigay line. In an interview broadcast on ABC television in July, Bush said his administration had "no litmus test" that automatically excludes gays and lesbians from staff positions, and in an interview in August, he said that if he learned one of his grandchildren were gay, he would embrace him but discourage him from becoming a gay rights activist.

Throughout September, Quayle appeared to back off the antigay rhetoric voiced at the convention weeks earlier. During a campaign stop in Los Angeles, for instance, he conceded that his party has a "conservative voice and a conservative philosophy" but said he does not support the exclusion of gays and lesbians from it.

The backpedaling did not sit well with the religious right. After Bush's July ABC interview was broadcast, Richard Land, executive director of the Southern Baptist Convention Christian Life Commission, fired off an angry letter to the president expressing "outrage and a sense of betrayal" regarding his no-litmus-test answer.

The religious right's take-no-prisoners attitude toward homosexuality has painted the president and vice president into a corner, says Washington Post political reporter E.J. Dionne, author of Why Americans Hate Politics. Surveys consistently indicate that most voters oppose antigay discrimination, but the religious right -- one of the Republican Party's most powerful constituencies -- demands strict adherence to its antigay position, he says.

"The religious right controlled many of the Republican slates at the convention and Bush tried to mollify the Right," Dionne says. "But I think the Republicans went further than they had ever intended. They have spent the weeks after the convention trying to look like unbelievable moderates on gay rights. In Los Angeles, Quayle even used the politically correct terminology -- gay and lesbian rather than homosexual."

As a campaign theme, the family-values issue has had little impact according to a Sept. 16 New York Times/CBS News poll. Only about 1% of the respondents to the survey said the issue was their primary concern, while nearly 50% said the economy was the most important campaign issue. In fact, the Republicans' use of the theme risks alienating mainstream voters, says political analyst Kevin Phillips, author of The Politics of Rich and Poor. Not only does the theme offer no solution to pressing problems like lack of affordable healthcare and rising unemployment, but its use makes Bush appear to shirk responsibility for the weak economy, he says.

In addition, Phillips says, use of the theme draws public attention to the Republican Party's close relationship with the archconservatives like televangelist Pat Roberston, Liberty University president Rev. Jerry Falwell, and Eagle Forum president Phyllis Schlafly. "These people are not high on America's list," Phillips says. "It undercuts the whole idea of family values to identify family values with the religious right. Most Americans think that Robertsons' rantings are off-the-wall."

University of Southern California law professor Susan Estrich, who managed Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis's unsuccessful 1988 campaign says that Bush's lack of a domestic policy agenda created a vacuum in the Republican Party that the religious right is eager to fill. "George Bush stands for nothing," she says. "What the convention demonstrated more than anything is that he will say or do anything to get votes."

Despite its gains in the presidential campaign, the religious right's influence is not confined to national politics. Some of its most far-reaching advantages have been on the state and local levels. "The religious right knows that the real battle over social issues is at the local level," says Mike Hudson, legal counsel for the liberal political group People for the American Way. "The 90s will be a great battle for grass-roots control."

Both the Oregon and Colorado initiatives have been well-funded, and each has a good chance of receiving voter approval. In September, Robertson donated $20,000 to the Oregon Citizens Alliance, the group that is backing the Oregon initiative, and announced that he would start setting up field operations in the state.

On the same day that the Oregon and Colorado initiatives will go to the voters, residents of Portland, Me., will consider a ballot referendum that would repeal a citywide ban on antigay discrimination that was approved by the city council in May. The referendum was prepared by the Christian Civic League of Maine, an antigay group that said in a public statement that opposition to gay civil rights protection is "probably the most significant moral issue facing Maine in the history of our state." In September a fundamentalist group in Kansas City, Mo., announced that it would seek to place a similar referendum on the ballot there.

Last spring, antigay activity directly related to the religious rights growing clout flared in Florida, where the American Family Association, an antigay group headed by conservative activist Donald Wildmon, successfully lobbied the Gainesville city commission to approve a resolution condemning gay rights guarantees. At the same time, a ban on antigay discrimination enacted in Tampa suffered a setback when a circuit court judge ruled that a referendum on it must appear on the November general-election ballot.

In the neighboring Alabama, meanwhile, the state legislature enacted an Eagle Forum-backed bill that requires sex education curricula in public schools to stress that same-sex intercourse is a crime under the state's sodomy law. Legislators also passed a bill that forbids state funds to be allocated to gay student groups.

Frequently, the religious right works to influence politics from within by dominating county Republican Party organizations. When Citizens for Liberty, an antigay group that supports establishment of a militia and elimination of the Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Reserve System, gained control of the Republican central committee of Santa Clara County Calif., the California Republican Leauge, a moderate group, was so alarmed that it warned the country's rank-and-file Republicans that the group's agenda includes "a call for the death penalty for abortion, adultery, and unrepentant homosexuality."

In Harris County, Tex., this year's Republican platform alleges that homosexuality "leads to the breakdown of the family and the spread of deadly disease" and calls on the federal and state government to enforce "all laws prohibiting homosexual conduct."

Building on its gains in county Republican organizations, the religious right has targeted state parties as well. Harriet Stinson, director of the California chapter of Republicans for Choice, says the religious right "has literally taken over" the California Republican Party by purging moderate Republicans from county central committees, running religious candidates for local and statewide seats, and harassing moderate party officials until they take extreme positions.

The religious right's gains in California have been so great that Gov. Pete Wilson, who was considered a moderate when he was elected in 1990, has been "virtually shut out of his own party," Hudson says. "The Right has made Wilson its lapdog on social issues," he adds, attributing Wilson's veto last year to the governor's efforts to appease the religious right. When running for governor less than a year earlier, Wilson had indicated that he supported the ban.

In primary elections for the California state assembly in June, 12 of 16 candidates endorsed by the Conservative Coalition, a network of religious right groups, won their races, a better track record than that compiled by Republican candidates who had Wilson's endorsement. The coalition donated to its candidates nearly $700,000, more than any other political action committee in the state, according to Common Cause, a nonpartisan public-interest group.

The coalition is funded by a small group of businessmen in conservative Orange County. One of them is Howard Ahmanson, whose net worth is estimated to be more than $100 million. In 1985 Ahmanson told the Orange County Register that his goal is the "total integration of biblical law into our lives."

The religious right touts the 1990 San Diego municipal election as a model it hopes to replicate nationwide. In the election, the religious right ran a slate of 90 little-known candidates for city council and for boards overseeing schools, hospitals, and public utilities. After playing down their affiliation with the religious right, 56 of the candidates were elected.

The religious right "takes advantage of voter apathy and the anti-incumbency mood in the country," says Kathy Frasca, a founder of the Mainstream Voter Project, a San Diego group that monitors the religious right. In San Diego the right-wing candidates' bids for office would have failed if voters had been better informed about the candidates' ties to fundamentalists, she says.

The religious right has made inroads in state parties outside California as well. Last May, Washington State's Republican Party adopted a platform that calls for gays and lesbians to be barred from jobs as teachers or health care workers. The platform also advocates corporal punishment for students and denounces the practices of witchcraft and yoga in public schools. Adoption of the platform infuriated several longtime moderate Republican activists. King County Republican platform committee chairman Brett Bader called it "the most seriously off-base reckless, and damaging platform I have ever seen."

In Iowa the state Republican Party adopted a platform this summer that calls for strict enforcement of sodomy laws, mandatory reporting of the names of people who test positive for antibodies to HIV, the virus believed to lead to AIDS, and the obligatory teaching of creation science in place of evolutionary theory.

And in a face-off last year that underscored the animosity between the Republican Party's moderate and conservative wings, delegates to a Minnesota state Republican Party convention in St. Cloud walked out of a speech by Gov. Arne Carlson, a Republican, to protest Carlson's decision to allow himself to be named an honorary sponser of a Minneapolis fundraiser conducted by the Human Rights Campaign Fund, a gay political group.

The religious right's strategy has been developed and implemented by a network of organizations and leaders who are largely unknown to the public but familiar to Republican power brokers. Many of the religious right's leaders-- including the Southern Baptists Convention's Land; Gary Bauer, executive director of the Family Research Council; Beverly LaHaye, president of Concerned Women for America; and Bob Jones III, president of Bob Jones University -- met with President Bush in the White House in April. After meeting, the fundamentalists told reporters that President Bush had convinced them he shares their belief that gays and lesbians pose the greatest modern threat to traditional American values.

Along with Morris Chapman, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, a 15-million-member denomination that is the nation's largest Protestant sect, Land has been instrumental in mobilizing support for conservative causes. Under the leadership of Chapman and Land, the Southern Baptist Convention this summer expelled two North Carolina congregation -- Pullen Memorial Baptist Church and Binkley Memorial Baptist Church -- for blessing the union of two gay men and licensing a gay minister.

Still, Robertson remains the religious right's most influencial and well-known leader. Although Robertsons' 1988 bid for the Republican presidential nomination failed, the Washington Post's Dionne says the attempt brought national prominence to the Christian Coalition, Roberston's political organization, which has more than 2 million members nationwide.

Robertson's clout is further increased by his 60% ownership of International Family Entertainment Inc. (IFE), which operates the Christian Broadcasting System cable television network and is the world's largest religious programmer. A recent public stock offering conducted by the company raised more than $150 million for Robertson and his son Timothy.

Shortly after completing the stock offering, Robertson made a $6-million bid for United Press International (UPI), a new service that declared bankruptcy earlier this year. The deal eventually collapsed, but had it been consummated, it would have provided an inroad into the mainstream media that Robertson has long sought.

At the time he made his offer for UPI, Robertson noted that "in the '70s, we began praying for all aspects of life -- religious life, governmental life, education, the media, arts, and entertainment -- and all of these facets are part of what God wants to touch. He wants to touch it with his truth and his love. This is one little chance for that to happen." On Sept. 21, Robertson took another step into the mainstream media, announcing that IFE had agreed to in principle to purchase MTM Entertainment Inc., a Studio City, Calif., firm that produces the television series Evening Shade for $68.5 million.

Such influence seemed unthinkable in the '70s, when the religious right was largely unorganized and split along ideological lines. Its ranks included relative moderates like Bauer, who advocate repeal of gay civil liberties protections, and extremists like R.J. Rushdooney, who advocate establishment of a Bible-based legal system under which gays and lesbians would be subject to the death penalty.

Ronald Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign was the pivotal event that spurred the religious right to organize, and fear of gay political advances have helped keep the coalition together since then, says Fred Clarkson, a journalist who has written extensively about the religious right. "Getting the Right to overlook its differences and work together was a real accomplishment," he says.

Seeing a well-organized bloc of votes, the Republican Party actively courted the religious right during the late '70s and the '80s. The effort paid off: Hudson of People for the American Way says that the religious right was instrumental in electing Republican presidents in the 1980, 1984, and 1988 elections.

However, the courtship also narrowed the party's appeal to mainstream voters. "I really don't believe that the majority of voters goes for the hatred and extremism exemplified by the religious right," Estrich says. "I hope that Bush keeps sucking up to the Right. It makes the Democrats that much better off."

Even within the Republican Party, the power wielded by the religious right has been a cause for concern, creating a bitter rift between social conservatives like Robertson and Quayle and libertarians like Weld and the Department of Housing and Urban Development head of Jack Kemp. While the social conservatives concern themselves primarily with moral issues, the libertarians concentrate largely on economic matters.

The rift was illustrated dramatically in July, when former Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, a staunch right-winger who was the Republican Party's presidential candidate in 1964, shocked political insiders by throwing his support behind a proposed ban on antigay bias in Phoenix. In announcing his position on the ban, Goldwater scolded the Republican Party, saying it allowed the religious right to lead it away from discussion of our substantive issues.

"Under our constitution, we literally have the right to do anything we may want to do as long as the performing of those acts does not cause any damage or hurt to anybody else," Goldwater said. "I can't see any way in the world that being gay can cause damage to somebody else."

The schism within the Republican Party has been exacerbated by the recession, Dionne says "In good economic times, social conservatives could vote on fairly social issues, and upscale Republicans, who tend to be fairly liberal on social issues, could vote their pocketbooks," he says. "Once the economic lubricant disappeared, the frictions heat up."

The national debate over abortion has also widened the rift within the Republican Party. This year, national Republican officials adopted the toughest, antiabortion platform plank in history, forbidding abortion even for pregnancies that result from incest or rape. Adoption of the plank caused Republican abortion rights proponents to step up their efforts to neutralize the religious right's influence within the party.

Rep. Tom Campbell (R-Calif.), a moderate Republican known for his support for gay and abortion rights, contended during his unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination for a Senate seat in June that because conservatives have long opposed government intervention in private matters, a truly conservative position would be one supporting abortion rights and gay rights guaranteed.

"It's actually a conservative position to oppose discrimination," Campbell says. "There is no reason that groups that make bigotry a priority couldn't feel at home in the Democratic Party. There's nothing particularly Republican about imposing one's values on others."

But few other moderate Republicans are willing to link gay rights and abortion. Stone of Republicans for Choice says that even gay and lesbian Republicans "understand that it's best to keep the two issues seperate. It remains to be seen if there is any way to work together. The likelihood of gay rights will ever be specifically addressed by the party is not great."

As a result, the battle lines will continue to be drawn for years to come. Both gays and lesbians and the religious right "feel that they have been dumped on," Dionne says. "The religious right feels it lost its culture in the '60s. It feels that it has been ridiculed by the media and by society in general. A lot of it's anger is being expressed through attacks on gays and lesbians."

Both sides agree that there is no middle ground. "This is the beginning of a sophisticated, well-financed backlash against gay and lesbian inroads into the media and culture that's fueled by the religious right," says Robert Bray, a spokesman for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, a lobbying group. Adds Steve Sheldon, a spokesman for the Traditional Values Coalition, a Southern California antigay group: "It's a holy war that can only have one winner."