The U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Masterpiece Cakeshop, Lts., v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission focuses on the treatment Masterpiece owner Jack Phillips received at the commission, saying he encountered "a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs motivating his objection" to making a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

Because of that, "The Commission's actions in this case violated the Free Exercise Clause" applying to religious freedom in the U.S. Constitution, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the court majority. The ruling was 7-2, with Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor dissenting. The commission had found that Phillips violated Colorado's antidiscrimination law by refusing the cake to Charlie Crag and David Mullins, and Colorado courts had upheld that decision, paving the way for Phillips's appeal to the Supreme Court.

The high court's decision, issued today, was tailored narrowly, applying only to this case, but it sets the scene for more court clashes over the right to turn away LGBT customers and, whether or not the high court intended, gives some ammunition to those who would argue for this right. And some conservative justices thought the ruling did not go far enough. Kennedy wrote:

"The laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect gay persons and gay couples in the exercise of their civil rights, but religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression. ... While it is unexceptional that Colorado law can protect gay persons in acquiring products and services on the same terms and conditions as are offered to other members of the public, the law must be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion. To Phillips, his claim that using his artistic skills to make an expressive statement, a wedding endorsement in his own voice and of his own creation, has a significant First Amendment speech component and implicates his deep and sincere religious beliefs."

Phillips "was entitled to a neutral and respectful consideration of his claims in all the circumstances of the case," Kennedy wrote. He continued:

"That consideration was compromised, however, by the Commission's treatment of Phillips' case, which showed elements of a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs motivating his objection. As the record shows, some of the commissioners at the Commission's formal, public hearings endorsed the view that religious beliefs cannot legitimately be carried into the public sphere or commercial domain, disparaged Phillips' faith as despicable and characterized it as merely rhetorical, and compared his invocation of his sincerely held religious beliefs to defenses of slavery and the Holocaust. No commissioners objected to the comments. Nor were they mentioned in the later state-court ruling or disavowed in the briefs filed here. The comments thus cast doubt on the fairness and impartiality of the Commission's adjudication of Phillips' case. Another indication of hostility is the different treatment of Phillips' case and the cases of other bakers with objections to anti-gay messages who prevailed before the Commission. The Commission ruled against Phillips in part on the theory that any message on the requested wedding cake would be attributed to the customer, not to the baker. Yet the Division did not address this point in any of the cases involving requests for cakes depicting anti-gay marriage symbolism. The Division also considered that each bakery was willing to sell other products to the prospective customers, but the Commission found Phillips' willingness to do the same irrelevant. The State Court of Appeals' brief discussion of this disparity of treatment does not answer Phillips' concern that the State's practice was to disfavor the religious basis of his objection."

"For these reasons, the Commission's treatment of Phillips' case violated the State's duty under the First Amendment not to base laws or regulations on hostility to a religion or religious viewpoint," Kennedy went on, adding, "The State's interest could have been weighed against Phillips' sincere religious objections in a way consistent with the requisite religious neutrality that must be strictly observed. But the official expressions of hostility to religion in some of the commissioners' comments were inconsistent with that requirement, and the Commission's disparate consideration of Phillips' case compared to the cases of the other bakers suggests the same."

Kennedy, who has authored all the court's pro-LGBT rights decisions, cautioned that he was not ruling for a blanket license for business owners with anti-LGBT religious beliefs to discriminate against LGBT people. "The outcome of cases like this in other circumstances must await further elaboration in the courts, all in the context of recognizing that these disputes must be resolved with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market."

Justice Elena Kagan wrote a separate opinion concurring with Kennedy. The different treatment of Phillips and the bakers who refused to make cakes with antigay messages "could ... have been justified by a plain reading and neutral application of Colorado law--untainted by any bias against a religious belief,* she wrote. "I read the Court's opinion as fully consistent with that view." She continued:

"Colorado law, the Court says, 'can protect gay persons, just as it can protect other classes of individuals, in acquiring whatever products and services they choose on the same terms and conditions as are offered to other members of the public.' ... For that reason, Colorado can treat a baker who discriminates based on sexual orientation differently from a baker who does not discriminate on that or any other prohibited ground. But only, as the Court rightly says, if the State's decisions are not infected by religious hostility or bias. I accordingly concur."

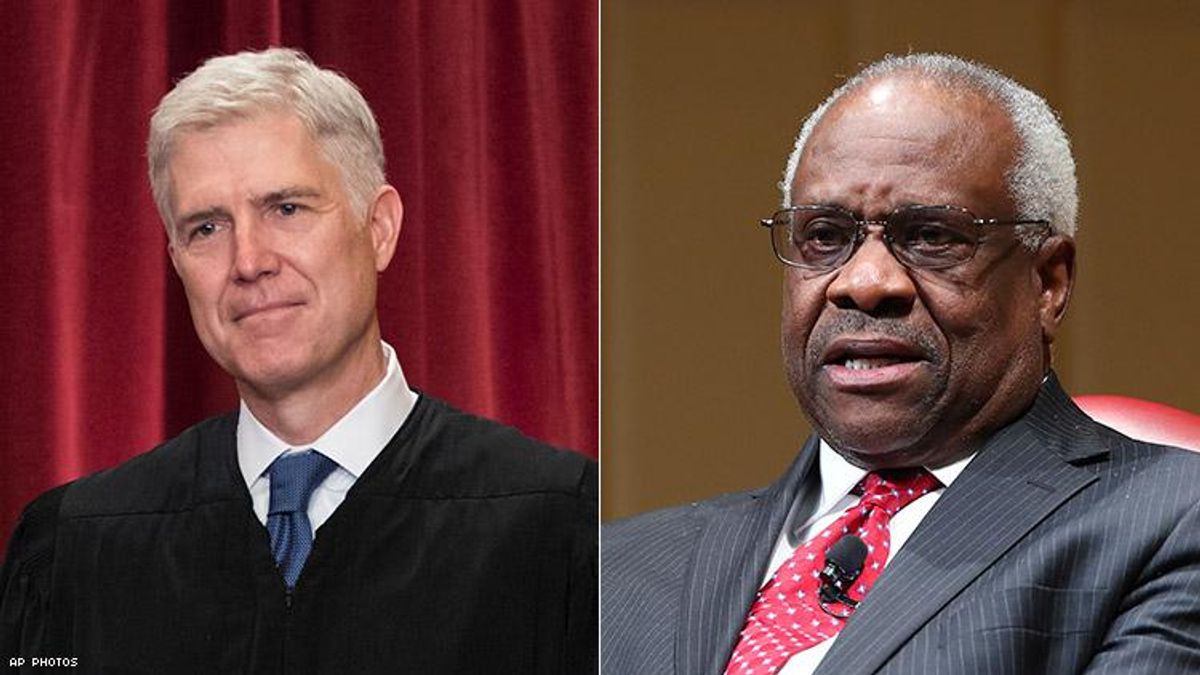

Neil Gorsuch, the court's newest justice, appointed last year by Donald Trump, also wrote a concurring opinion, but he took issue with some of the assertions in Kagan's concurrence and in Ginsburg's dissent:

"In the face of so much evidence suggesting hostility toward Mr. Phillips's sincerely held religious beliefs, two of our colleagues have written separately to suggest that the Commission acted neutrally toward his faith when it treated him differently from the other bakers--or that it could have easily done so consistent with the First Amendment .... But, respectfully, I do not see how we might rescue the Commission from its error."

The other bakers whose cases came before the commission had refused to sell cakes with antigay messages to a man named William Jack. They said they were not discriminating because they would not make those cakes for any customer. Phillips, regarding his refusal to create the wedding cake for Craig and Mullins, "testified without contradiction that he would have refused to create a cake celebrating a same-sex marriage for any customer, regardless of his or her sexual orientation," and indeed, refused such a request from Craig's mother, Gorsuch wrote. Because of this, "the facts show that the two cases share all legally salient features," he added.

In a footnote to her dissent, Kagan objected to Gorsuch's reasoning. "The cake requested was not a special 'cake celebrating same-sex marriage,'" she wrote. "It was simply a wedding cake--one that (like other standard wedding cakes) is suitable for use at same-sex and opposite-sex weddings alike."

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part, in which Gorsuch joined. Thomas said the court should not only have ruled for Phillips's free exercise of religion, but should have considered his freedom of speech, which Kennedy's ruling did not address because the court "has some uncertainties about the record." Thomas's opinion, in which Gorsuch joined, contended that Phillips's custom wedding cakes fall under the Constitution's free speech guarantee because they are "expressive conduct."

"Phillips is an active participant in the wedding celebration," Thomas wrote. "He sits down with each couple for a consultation before he creates their custom wedding cake. He discusses their preferences, their personalities, and the details of their wedding to ensure that each cake reflects the couple who ordered it. In addition to creating and delivering the cake--a focal point of the wedding celebration--Phillips sometimes stays and interacts with the guests at the wedding. And the guests often recognize his creations and seek his bakery out afterward. Phillips also sees the inherent symbolism in wedding cakes. To him, a wedding cake inherently communicates that 'a wedding has occurred, a marriage has begun, and the couple should be celebrated.'"

Of Phillips's statement to Craig and Mullins, "I just don't make cakes for same sex weddings,'" Thomas wrote, "It is hard to see how this statement stigmatizes gays and lesbians more than blocking them from marching in a city parade, dismissing them from the Boy Scouts, or subjecting them to signs that say 'God Hates Fags'--all of which this Court has deemed protected by the First Amendment. ... Moreover, it is also hard to see how Phillips' statement is worse than the racist, demeaning, and even threatening speech toward blacks that this Court has tolerated in previous decisions."

The court's marriage equality decision, Obergefell v. Hodges, does not diminish Phillips's right to oppose same-sex marriage, Thomas continued:

"In Obergefell, I warned that the Court's decision would "inevitabl[y] ... come into conflict' with religious liberty, 'as individuals ... are confronted with demands to participate in and endorse civil marriages between same-sex couples.' This case proves that the conflict has already emerged. Because the Court's decision vindicates Phillips' right to free exercise, it seems that religious liberty has lived to fight another day. But, in future cases, the freedom of speech could be essential to preventing Obergefell from being used to 'stamp out every vestige of dissent' and 'vilify Americans who are unwilling to assent to the new orthodoxy.'"

Finally, Ginsburg, writing the dissenting opinion for herself and Sotomayor, disagreed that the civil rights commission overall showed hostility to Phillips's religious beliefs. "The different outcomes the Court features [between his case and the William Jack case] do not evidence hostility to religion of the kind we have previously held to signal a free-exercise violation, nor do the comments by one or two members of one of the four decisionmaking entities considering this case justify reversing the judgment" against Phillips, she wrote. She added:

"The fact that Phillips might sell other cakes and cookies to gay and lesbian customers4 was irrelevant to the issue Craig and Mullins' case presented. What matters is that Phillips would not provide a good or service to a same-sex couple that he would provide to a heterosexual couple. In contrast, the other bakeries' sale of other goods to Christian customers was relevant: It shows that there were no goods the bakeries would sell to a non-Christian customer that they would refuse to sell to a Christian customer."

"Whatever one may think of the statements in historical context, I see no reason why the comments of one or two Commissioners should be taken to overcome Phillips' refusal to sell a wedding cake to Craig and Mullins," she added, concluding that she would have affirmed the Colorado court rulings upholding the commission's decision.

Read the full ruling, the concurrences, and the dissent here.