Chase Strangio, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, is "the face of the whole legal battle for trans rights in the U.S." At least, that's how a friend of mine recently described him. And from what I can tell, he never seems to sleep, never seems to stop. If he's not in some courtroom litigating against a new state law, he's on the news talking about it or posting a thread of resources and responsive actions for his nearly 160,000 combined social media followers to take. To paraphrase the title of a Sarah Jessica Parker movie I've never seen: I don't know how he does it.

Over the span of his career, Strangio has gone from an underpaid, overworked lawyer at an LGBTQ+ legal aid organization focused on direct services for queer and trans New Yorkers to a better-paid, still overworked lawyer working on cases that impact LGBTQ+ communities at large in the nation's highest courts. In tandem with the growth of his professional profile as a civil rights advocate, Strangio has leveraged his own celebrity along with the profiles of well-followed friends to shift public consciousness: appearing on the Emmys red carpet with Laverne Cox, raising $3 million in partnership with Ariana Grande, and hosting a series of Instagram lives. It's an all-angles, 24/7 defense of LGBTQ+ rights at a time when trans rights specifically are the ones most directly under attack.

Again, though, that's just how he's always appeared to me, whichever screen I saw him on. I don't actually know who Chase Strangio is, despite being briefly introduced through a mutual friend at a screening of Lizzie Borden's Working Girls that we all happened to be at a few years ago. I've technically spent hours on the phone talking to him, but always in the context of me being a journalist and him being an authoritative source on whatever I happened to be covering: an anti-trans sports bill here, an anti-trans order from the Trump administration there. But beyond those mutually transactional encounters, the man has always been a total mystery.

"One of my few criticisms of Chase is that he is so dedicated, he doesn't take breaks when he needs to," Chelsea Manning, the security consultant whom Strangio represented after she was incarcerated for leaking classified government documents, tells me. "He is so dedicated to the work that he does, and I think that's why his social life is so diminished."

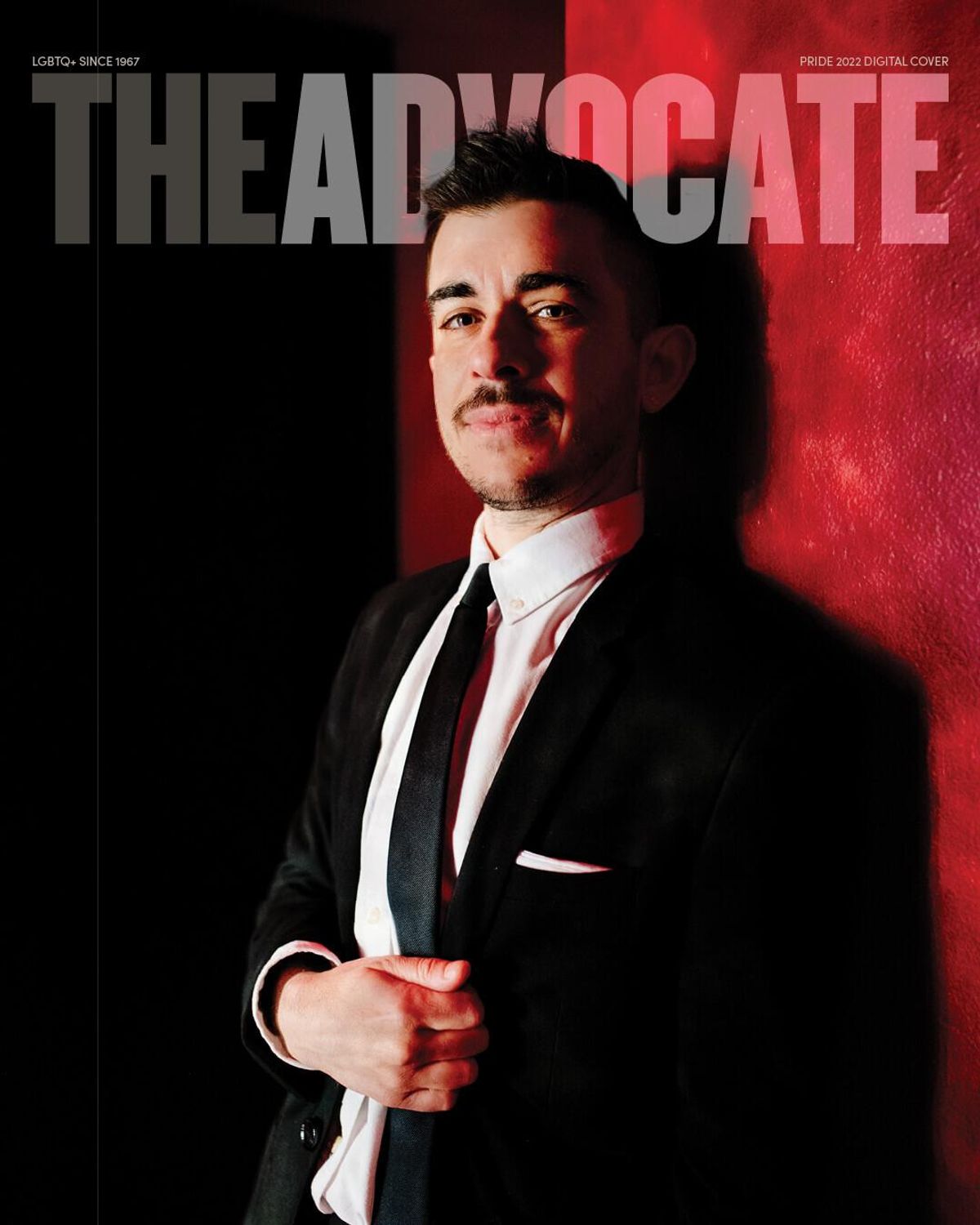

On a sunny Tuesday morning in early May, I arrived on set for Strangio's cover shoot, ready to meet the man behind all the advocacy. We were at New York City's Stonewall Inn--not just the site of the famed 1969 uprising against police brutality but a bar, the kind of place people might go to in order to kick back, have fun, and not check their work email for a few hours.

"Is this the first time in a while you've been in a bar?" I ask once the camera's initial clicks subsided. "I interviewed Chelsea Manning, and she said you're so dedicated to your job that you don't go out much."

"I'm not that dedicated!" he responds in mock outrage. "I mean, that's been hard during COVID. Everything feels different, but I still try to integrate some spaces into my life that are not about work. What's also hard in this moment is that whenever I go to places that are very queer, the likelihood of being recognized is much higher than if I went to some straight bar where no one knew who I was."

I sarcastically suggest that he could try going to straight bars.

"I guess there are options," he laughs. "But yeah, I don't know that I've done the best job over the last decade in creating systems of rest and relaxation for myself."

"But I have been to a bar."

*****

Hailing from Newton, Mass., Strangio began his legal career shortly after graduating from Northeastern University School of Law in 2010. He worked as a lawyer at New York City's Sylvia Rivera Law Project, where he had interned one year prior. Working under the legal aid organization's founder, Dean Spade, whose vision he very much admired, Strangio represented trans folks incarcerated in New York state prisons and jails. Another influential figure was the late community organizer Lorena Borjas, with whom he created a now-defunct cash bail fund. "Lorena was a very frequent guest and comrade who would come into the office and push us to do more for the trans Latina community in Queens," he says.

Burned out by what he felt were the limitations of working at a small nonprofit -- not to mention stressed over student loans and the cost of starting a family -- he took a job as a staff attorney at the ACLU in 2013. Though the world of impact litigation proved a steep learning curve, Strangio gradually established himself as a leading figure in the legal battle over LGBTQ+ civil rights. Even if you somehow haven't heard of him, you're definitely familiar with the cases he's argued. He represented Manning during her final three years in prison for disclosing military intel to WikiLeaks, sex work activist Monica Jones, and embattled trans student-turned-activist Gavin Grimm. As a litigator, he also on worked Obergefell v. Hodges, which produced the 2015 Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage across the United States; 2016's Carcano v. McCrory (later Carcano v. Cooper), which led to the repeal of North Carolina's infamous law restricting trans people's public bathroom access; and Aimee Stephen's case which was combined with two others in Bostock v. Clayton County, where the Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act protects LGBTQ+ workers from employment discrimination.

In the two years since Bostock, Strangio's legal work and advocacy have focused largely on the growing number of anti-trans laws pushed forth by state legislatures nationwide. Lawmakers filed a record number of anti-trans bills in 2020 only to break that record the following year, introducing 150 pieces of legislation that would make trans people's lives--and those of their accepting parents and medical providers--needlessly difficult, if not fully criminalized. We're not even halfway through 2022, and already we're on track to break that record again, with 140 bills filed by mid-May alone.

"This is the third year where we're seeing this incredibly intense attack against trans people, but particularly trans youth," says Cathryn Oakley, state legislative director and senior counsel at the Human Rights Campaign. "The folks pushing these bills are the same opponents of LGBTQ equality we've had for decades: the Heritage Foundation, the American Principles Project, the Alliance for Defending Freedom--same old, same old. Their goal is to stop LGBTQ equality at any cost. They tried with marriage, it didn't work. They tried with bathrooms, it didn't work. They'll try anything they can to get a foothold and start pulling back LGBTQ equality."

As deputy director for trans justice with the ACLU's LGBT & HIV Project, a position he has held since 2019, Strangio is currently involved in "a million cases," by his count. One of them involves an Arkansas state law passed in 2021 that would have prohibited trans youth from receiving gender-affirming health care of any kind. The ACLU challenged it, prompting a federal judge to issue a temporary injunction, thereby preventing an untold number of trans kids in the state from being medically detransitioned against their will. "We are preparing for a trial in October," Strangio says.

In Texas, he is involved with a case pertaining to Gov. Greg Abbott's directive issued earlier this year ordering the state's Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate the families of trans kids, cravenly calling the provision of lifesaving gender-affirming medical care "child abuse." The case is spurring New York Times push alerts, and in addition to being in hearings, Strangio can be often found making corrections or bringing context to headlines on Twitter. There's another case in Idaho, which passed a sports ban on trans students in the early months of the pandemic. And then there's Connecticut: in Soule et al v. Connecticut Associations of Schools et al, involving three white cis girls--represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom--who were so upset over having to compete alongside two Black trans girls, they sued their state, claiming that its trans-inclusive policy for publicly funded athletics violated their rights under Title IX. "The cis girls are fine, of course," Strangio says. "They went on to receive athletic scholarships, even though their whole argument was based on the claim that they couldn't because their opportunities were supposedly compromised."

"I was really hoping that this year was going to be different, and it's just the worst," he says.

Outside of the courtroom, Strangio works overtime in his attempts to get the public to understand the battle raging inside it, making appearances on Democracy Now! and The Rachel Maddow Show as well as utilizing Twitter and Instagram to shape the public narrative in trans people's favor.

"Chase is such a legal mastermind," says Raquel Willis, a writer and activist who launched the annual Trans Week of Visibility and Action with him last year. "Chase is one of the fiercest defenders of bodily autonomy and self-determination that we have on a national level. He can get such crucial and often inaccessible understandings of legislation to our community. He is also a powerful strategist who spends most of his days figuring out how to preserve, protect, and demand more on behalf of our people."

But it's not just at the macro level: Manning spoke with me about how Strangio helped care for her after she got out of prison. The two of them spent the first week immediately following her release at a safe house in an undisclosed location in upstate New York. "I have no idea where it was to this day," she explains. She'd always felt safe with him, always trusted him. Unlike the "white shoe" lawyers who came before him, he never made her feel like she had to explain herself to him or defend why she wanted the things that she did, like access to hormone replacement therapy while she was incarcerated. The week upstate was no exception. Thanks to Strangio's help, Manning was able to re-enter the outside world with no reporters, no phones, and no spotlight glaring down on her. "Just chill vibes only," she recalls. "There was a sound system. We'd just jam out to pop music," a lot of EDM, drum and bass, rave music, and Selena Gomez--her picks, not his. He later helped her get her first debit card in years, changing her name and updating her account information.

"It was this life-changing moment, being able to access my own money again," she says. "I didn't have to ask people for money to go to the store. It had been so long. [Even after my release and the week upstate,] I was basically trapped for about 10 days without access to my own money. He helped me solve that."

*****

Throughout my interviews, I thought about something Laverne Cox had told me over the phone. The Emmy-winning actress, who recently starred in Netflix's Inventing Anna, said that she often reaches out to Strangio before doing an interview. "Chase is truly the most important legal mind in the United States when it comes to trans issues," she told me, adding that he always knows exactly how to distill even the most complicated legal matter into digestible talking points that she can mention during interviews.

While my own conversations with Strangio had felt intimate, more like talking to a new friend than an interview subject at times, they were still opportunities to convey some sort of messaging to the public--but then, what?

A few days after the Stonewall photo shoot, I meet him at the two-bedroom apartment in Queens that he shares with his kid, when they're not with their other parent. It was sparsely decorated: Precious Brady-Davis's I Have Always Been Me and Shon Faye's The Transgender Issue faced outward on a built-in shelf, resting beside a draped Pride flag; magnetic poetry on the fridge arranged to spell out "LGBTQ" in big letters; the record sleeve for Janet Jackson's "Nasty" propped up on the air conditioner; very little of anything on the walls. The two of them have lived here for about a year and a half, but--surprise--he's been too busy to fully figure out the decor.

Something he has fully figured out might be alarming for some, especially from the one-man, never-sleeping, trans rights defender himself.

"We're not going to see any wins like we did with Obergefell or Bostock," he says. "The courts have changed significantly. We have to contend with reality." The same applies to federal legislation, he adds, like the seemingly doomed Equality Act. "We're not going to see that type of transformative structural change in the coming years. In fact, we're more likely to see further regression and backlash."

When Arizona introduced a bathroom bill way back in 2013, "there was a sense that it was beatable," he continues. "Beatable in the sense of using law as a tool." But there's been a domino effect ever since the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that same year. That decision in Shelby County v. Holder enabled rampant voter suppression and gerrymandering of districts, "which is impacting whether and how you can beat things in state legislatures," Strangio says. "If in a state like Arkansas you have three people in the whole legislature who are even mildly supportive of trans rights, it's really hard to stop anti-trans bills." Defending trans rights through the courts is equally daunting thanks to the 200-plus federal court judges appointed by former President. Donald Trump. Even if the ACLU, for example, were able to get a case involving trans rights before the conservative-majority Supreme Court, it'll likely fare no better than the fate Roe v. Wade appears headed for.

So why is he a lawyer if he doesn't believe that the law will ever truly save the community he spends all his time defending? "For me, it's the time," he explains. "I see it as a form of harm reduction--a delaying tool that gives people more time to mobilize, to build resources, and transform our living conditions in more meaningful ways than the law will ever allow."

Although he's not an optimist, he's no nihilist either. Strangio does believe that we should keep organizing and pushing lawmakers to cancel student loan debt, expand health care, and provide other basic necessities. He also believes that we should intervene wherever we encounter anti-trans antagonism, whether that's with friends and family or with our state and local governments. "Constituent contact is consistently the most effective way to kill a bill--I mean, other than being a corporation and buying off politicians," he says. "Even if you live in a state where these things aren't happening, you can organize and run call-in programs, calling voters to connect them to their lawmaker."

"We're going to be living in different times of extralegal care networks," he continues. "People should be prepared to think about how they're going to get access to medication, how they're going to get involved to get other people what they need whether that's Plan B, birth control, the abortion pill, hormones, puberty blockers. How are we collectivizing our access to care and redistributing it?"

As Strangio answered my questions on his expansive L-shaped couch, lounging cross-legged in a Boba Fett hoodie and Adidas cap, I realized how many things were competing for his attention: the notifications on his phone, which he frequently checked without pausing our interview; his black cat, Raven, who kept trying to drink out of our water glasses. About half an hour in, his apartment buzzer rang. The dinner he'd ordered for him and his kid had arrived. After giving his kid a plate in another room, he'd occasionally interrupt himself to check to see if they'd finished their salad, if they wanted another slice of pizza, before getting back to whichever of my questions he'd started answering.

"National efforts like passing the Equality Act or codifying Roe -- those are fine things, but Congress is not going to do it because federal legislation is a huge resource demand with low reward at this point, and it's just going to get challenged in court," he says. "I was at these two big LGBTQ organization events in the last 10 days--the GLAAD Media Awards and the Ali Forney Center gala. There's this drive for simple narratives at these events, so much talk about Disney and the 'don't say gay' bill in Florida -- which wasn't just about gay people -- and I'm like... this is how we got ourselves here! I get that people's capacity is so limited, but we just have to be able to hold more nuance. I'm also like--hey! Raven!"

His cat had started tearing up the side of the couch.

"I got you these scratching things!" he says, pointing to the nearest one. "Cats are so demonic, but, like, I chose to get him." He picked up his cat and cradled him, talking to Raven in the sing-songy, cutesy baby voice in which most pet owners are fluent. "And he's going to scratch fu-u-urnitu-u-ure, which is why I don't even have nice thi-i-ings, so it's fi-i-ine." Another problem dealt with--now onto the other 87.

All photography by Hunter Abrams for The Advocate at Stonewall Inn.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella