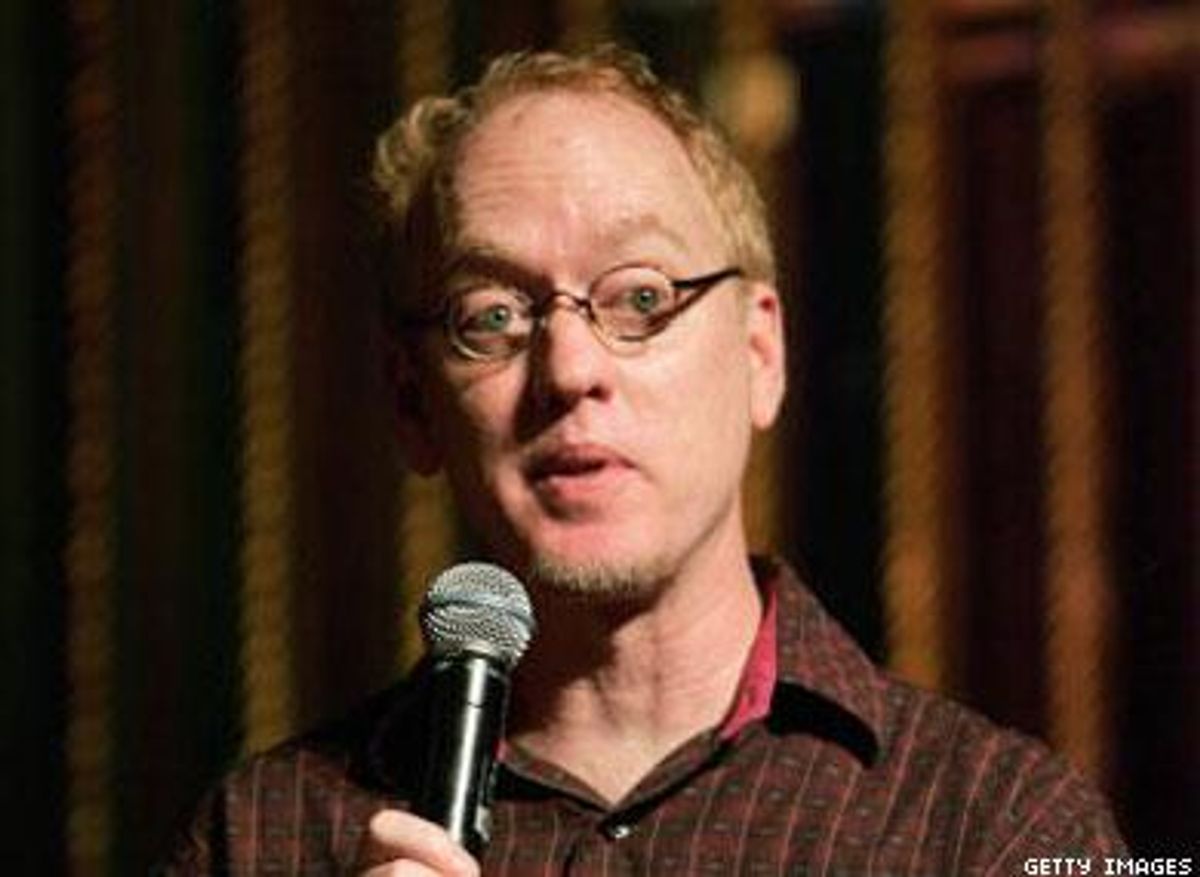

Andrew's Story

In the middle of my life, I am surprised to

discover that I am the bad guy. I have been selfish,

unfaithful, disloyal. I have hurt others, used

strangers, done shameful things to preserve my secrets.

I am 40 years

old. I have spent much of the past five years a slave to

crystal meth. It still calls out to me, despite the loathing

I now feel. Unlike the many others I have tried, this

drug has a distinct voice: the voice of thousands of

men, wanton and sinewy and accessible. The drug still

calls me to join their brotherhood, to be initiated all over

again into their cabal of wrongful oh-so-rightness.

I caused

monumental damage and hurt. My lovely partner, Patrick,

suffered the knowledge of my infidelities and

witnessed my mental, physical, and spiritual decay.

But I was unable to resist what crystal offered, that

beautiful, sensual comfort in my own skin. When the torch

hit the bowl and the hissing vapors were inhaled, all

fear, self-loathing, sorrow were suddenly eradicated.

My body, of which I am often severely critical, was

perfect.

As with most of

my addicted brothers, crystal, for me, was linked

inextricably with sex. It was terrifyingly easy to find

others like myself online. All you do is create a

profile that contains "party" or

"PNP," meaning "party and play."

These parties are

not the cake-and-candle variety. "Party" is

the euphemism for a cluster of speeding,

clenched-jawed, sweating men who have been reduced by

crystal meth to the status of rutting animals, each

aware only of his own distorted desires. But there was a

temporary illusion of closeness that felt strangely

comforting to a man like me, who grew up afraid to

show affection for male friends, because I was afraid

it would telegraph the secret of my orientation.

I had snorted

methamphetamine in various forms. It was extremely painful,

so I did it only rarely. Besides, my job as director of

global production for Steven Spielberg's Shoah

Foundation had required intense focus and global

travel. But I'd left that job and was experiencing my

first bout of extended unemployment when a friend

introduced me to the art of smoking the crystals

instead of crushing and snorting them. The incredible

high guaranteed that I would try this again, and I did. Day

in, day out. I began to disappear for hours . I started to

manufacture tapestries of lies to keep Patrick off

balance. He doesn't use drugs, so he was easily

deceived.

For a time, the

lies caused me pain. But lying became second nature, and

the chemicals effectively dealt with any guilt. I spent more

time orchestrating my next score than looking for

work. The fact that Patrick was now supporting us

barely registered in my now one-track mind. I began to

siphon money out of our accounts to fuel secret sex and drug

binges. As I sank deeper into the world of the

tweaker, Patrick grew suspicious, the money well began

to dry up, and I began to compromise myself in

increasingly demeaning ways to obtain the drug.

Why

couldn't I stop using? Was it a question of deficient

character, some flaw in the weave of my moral fiber? I

stopped caring what the answer might be. The molecules

of what had been Andy had gradually slipped out of my

lungs through the pipe stem and into the ether, replaced

with molecules of similar appearance but faulty

design.

At one point,

unable to procure the drug, I experienced a free fall back

into reality. I hit hard. In the throes of this depression I

finally told Patrick a tame version of the truth. He

insisted that I go to 12-step meetings, and I attended

about three before I scored and started my descent all

over again, exercising additional caution to cover my

tracks.

I was soon a

zombie, alternating between manic anxiety and euphoria,

sweating excessively, thinner than I was in high school. I

was cautious about undressing in front of Patrick

because my legs were covered with red speed bumps,

many of which I had hacked at, in the obsessive way of

the tweaker, until they refused to heal. When Patrick

confronted me one day, I denied using. Unfortunately,

he had found my stash: drugs, pipe, torch, and a

recent addition: a syringe.

Patrick,

understandably, asked me to leave to give him time to think.

What happened next is a disgraceful blur: a trip to my

dealer, a sleazy motel, stacks of pornography, and a

three-day crystal-and-GHB binge that I was hoping I

would not survive.

But survive I

did, and I emerged from that seedy, smelly room three days

later and checked myself into rehab. I'm not sure I

wanted to live; I simply knew I wasn't able to

die.

I made many

friends in rehab, even with sores on my arms and a

butane-lighter burn on my forehead. The comfort zone

abruptly shattered when Patrick attended a group

session and explained to all my new friends and their

families that I had stolen money, slept around, and was the

most selfish man to ever walk the face of this earth. I saw

jaws drop and eyes turn to stare. There was no hiding

from this stored pain and anger, which has since

become known as Andy's "truth enema."

I wish I could

say that that trip to rehab straightened me out. But a

year later I relapsed with a vengeance. I told myself it was

OK if I didn't engage in infidelities; instead,

I soaked up Internet porn like a sponge. Eventually,

psychosis set in. I heard voices in running water,

talked to people who lived in the trees behind our house. I

returned to rehab, but I was asked to leave for

swearing at the facility director.

I developed

meningitis, then peritonitis; my appendix began leaking but

I was too tweaked to notice. The appendix ruptured; I

almost died of toxic shock. It took six gallons of

fluid to clean out my innards. I was in the hospital

four weeks. On release I stayed clean for just a few months.

Even the ragged scar running the length of my belly

didn't make me question my loyalty to crystal.

And then,

miraculously, out of nowhere, deliverance. I finished a

binge, and I knew I was done. I threw away the pipe

and told an understandably skeptical Patrick that I

was now done with this chapter in my life. It took

months for him to even begin to think I might be telling the

truth. It was as if the underground current I'd

been surfing for years suddenly broke surface and

spilled me out into daylight.

I have no

explanation for this sudden renunciation of what had been

the strongest influence in my life. What I do know is

that I am blessed. That I have been allowed back

inside the circle of grace that Patrick represents

amazes me. That he can separate the Andy he fell in love

with from the Andy I became is incomprehensible. But

it's one of the reasons I respect him more than

any other man I know.

Crystal meth

targeted me because I lived self-consciously, self-absorbed

as only the truly insecure can be. So many of us carry the

remnants of shame and self-hatred that growing up gay

in an intolerant society creates. Crystal is so deadly

to us partly because the first hit can simulate a

well-being that would take years of therapy to create.

Sadly, it is an illusion.

Occasionally,

without warning, I remember the faces of other addicts I

crossed paths with--zombies wandering the halls and

stalls of a bathhouse, speed freaks slamming in a

porn-flickering bedroom. I sometimes cry when I think

of these men I touched but never knew. I see beyond the

glassy eyes and into the person trapped inside,

desperate, scared, holding on to what little is left,

knowing there will be less tomorrow. I want to help

them, and I realize suddenly that they are me.

For now, I am

saved.

Related LinksCrystal Meth AnonymousCrystalRecovery.comDanceSafe.orgLifeorMeth.comAlanon

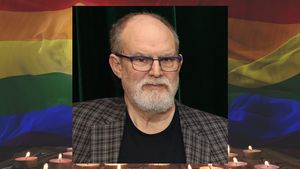

Patrick's Story

Andy had been unemployed for a few months after

the dot-com he produced for went belly-up. The

moodiness and frustration he'd been exhibiting

seemed explainable. Why he was taking it out on me, however,

was not clear. After a weekend in Oakland, Calif.,

with friends, he seemed tired, irritated, and at times

even mean. This wasn't the Andy I had known for

seven years.

I hadn't

really been exposed to drug addicts and their

behaviors--at least not to crystal meth addicts.

So Andy's nocturnal hours, mood swings, and

sometimes impulsive actions seemed more indicative of some

sort of mood disorder to me.

As I was

pondering the situation, the thought popped into my head: I

wonder if Andy's a drug addict? How naive I was,

in retrospect. Just an hour after that odd thought

crossed my mind, Andy told me that he was in fact a

drug addict and that he had binged in Oakland.

I was either

psychic or stupid.

He was feeling

sick. So was I. I took a deep breath and laid down the

law. I told him he had to start a 12-step program

immediately. I told him that he was risking losing me,

our home, our pets -- everything. He seemed to grasp

the gravity of the situation and vowed to do everything I

asked, or rather demanded, of him. I believed him.

He started going

to meetings the very next day. I watched carefully for

"signs," whatever they might be. I went to

Al-Anon meetings myself but failed to grasp the real

tenets of the program. I was angry, vindictive, and

controlling. I was going to make him stop this. I became

more of a parent and less of a partner. As you can

guess, it didn't help either of us.

It had been many

months since my mandate that Andy attend the program. He

had continued with it for a while but then found numerous

excuses to avoid going to meetings. Things seemed back

to normal to a degree. His mood was more stabilized,

and he was nicer. There were still

"all-nighters" on the computer and occasional

periods when I couldn't account for his

whereabouts -- but there was always an explanation, and

it was always feasible -- at least to me.

Then I found the

stash. He had put his lighter, butane refill cartridge,

crystal, and a razor blade under a drawer in our bathroom.

Just as the thought that he might be an addict came

out of the blue, so came the instinct to look under

the drawer. I wasn't in the habit of looking in

odd places, but something told me to do it. I was instantly

saddened and angry and embarrassed for being so stupid

as to have believed him.

I confronted Andy

about my findings. He claimed that it was an old hiding

place. I told him I'd seen the same lighter just two

weeks ago on a coffee table. He was busted. His

demeanor changed.

Instead of acting

like an innocent man wrongly charged, he was defiant

and calm. This was the "drug" personality. I

told him he had to leave the house for a week for me

to think. He told me that I should be the one to go. I

reminded him that my name was on the mortgage. He left. I

was shaking in disbelief. What had I done wrong? How

could he be doing this? It felt like there was a third

person in the relationship bent on destroying us. The

Jekyll-and-Hyde effect was in full swing.

The weekend after

I kicked Andy out, I was furious, depressed, raging,

crying, terrified, and confused. I pretended not to care if

he killed himself at that point. I didn't know

where he went, and I turned my thoughts to protecting

myself. I hid my family heirlooms at friends'

houses for fear he would come back and steal them. I worried

constantly that the police were going to call. I went

to Al-Anon meetings and vented my anger at him. Kind

faces with more experience merely smiled reassuringly

and neither judged nor condoned my fury.

I prayed for any

sign that life would return to normal. In a blessed

coincidence, I saw Andy driving one day, many miles from our

home. I knew he was alive. I told myself I was glad

only that the car was OK.

A day later he

called me to get our insurance information because he was

checking into rehab. I gave him the group number and wished

him luck. I was punishing him with coldness for

screwing up my life.

At almost the

hour he checked into rehab, I got a job on a film that

would be shooting the entire time he was in there. My

schedule would be six-day weeks of 14-hour

night-to-morning shoots. I was also left alone to

prepare our house for sale. There was very little of me left

at the end of each day.

This was when

Andy called to ask me to participate in the family meetings

at the rehab center. I was furious that after all I'd

been through, he was asking for more--and at a

time when I had little to nothing to offer. But I

went.

I attended the

first moderated family meeting, in which addict-patients

got to apologize or express their feelings to their

significant others. I sat stone-faced as Andy promised

to make it all up to me. We were allowed to respond

after the addict's profession of determination. I let

it rip. I had always been private and not one to air

the dirty laundry. But in that moment I told Andy that

I didn't trust him, that he'd been

unfaithful (news to his mother, who sat next to me), that I

thought he was manipulative and abusive and every

other word one can use to describe someone they hate.

I told him that he'd forced me to resort to dishonest

tactics just to get to the truth. When I said I'd

seen his lighter a week earlier on the coffee table, I

was lying. The sickness of this was not lost on me --

lying just to get to the truth.

Andy seemed to

also realize that this was a watershed moment in our

relationship. My polemic became known in his rehab clinic as

"the truth enema." I told him in front

of his peers and family that I did not want to live

with him -- that when our home sold, we'd be looking

for different places. He was stunned by my

"strength." Ironically, I was

intoxicated by it. A doormat no more. Something worse. I was

a dictator.

Once I realized

that I had been punishing Andy for being an addict, I

changed my entire approach. I had loved this man for a

decade. My initial, and perhaps necessary, overkill of

self-protection gave way to a more loving manner of

dealing with "our" problem.

It took many

months for this punishing approach to give way to a more

balanced one. Through my time spent at Al-Anon, I finally

heard some more of the subtle and loving messages that

had eluded me during my angriest months. Going against

the tacit yet clear (silence can convey so much)

advice of my program friends, I let Andy back into my life.

I would not

recommend this to anyone, just as I would not recommend my

previous approach. It's too personal. I knew one

thing: I could live by my decision and, if necessary,

extract myself from the situation again.

So I asked Andy

to live with me again. We recombined households. We set

boundaries; honestly, some have been maintained and others

eroded. It's not perfect in a clinical sense.

But as I watch straight couples divorce over seemingly

minor differences, I can't help but think that

commitment counts only when you need it--and

that's when it's the most difficult to

maintain.

We can't

profess our love in our church, but that doesn't

matter to me too much at the moment. In my heart I

married this man long ago. He may relapse again. In

fact, statistics say he will. But I no longer define

him by an addiction he has to grapple with. I take measures

to protect myself. I champion his daily triumphs of

not using. I demand no less of him than if he

hadn't had this problem. I have more tools to deal

with a relapse should it occur. I thank God I never

tried that evil little chemical that is destroying so

many lives in our community. I work daily to make our

story end better than the countless tragic ones I've

heard.

Related LinksCrystal Meth AnonymousCrystalRecovery.comDanceSafe.orgLifeorMeth.comAlanon

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4