Voices

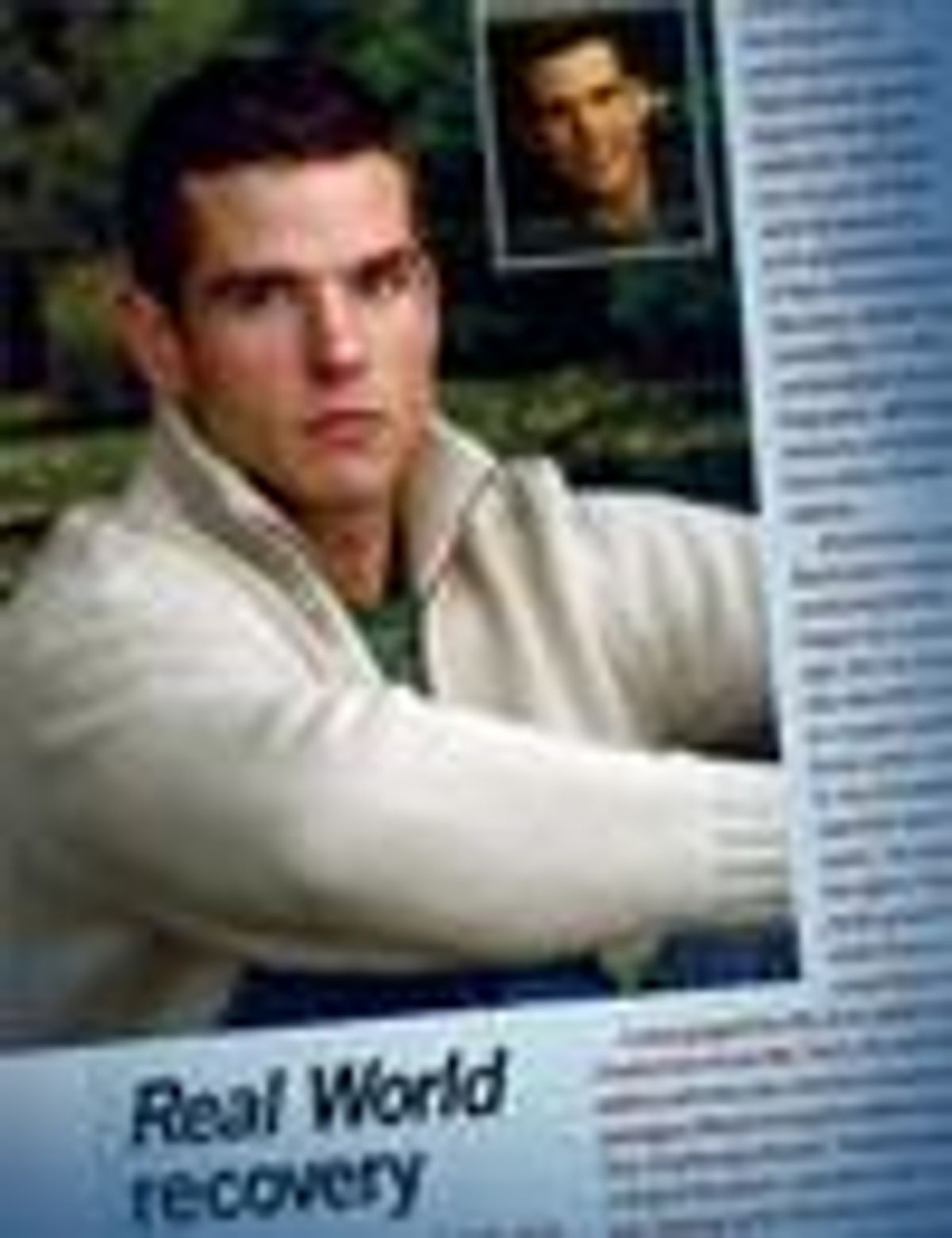

Real World recovery

Real World recovery

In a confessional new book, gay Real World alum Chris Beckman puts the spotlight on a new generation fighting addiction

Michael Giltz

September 12 2005 12:00 AM EST

November 15 2015 6:16 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Real World recovery

In a confessional new book, gay Real World alum Chris Beckman puts the spotlight on a new generation fighting addiction

"If I'd started using drugs like crystal meth in high school," says Chris Beckman, "I don't know if I would have graduated. Or lived."

Beckman had been in recovery from alcoholism and drug abuse for just a year when he joined the cast of MTV's The Real World in its 2002 Chicago season, thereby becoming most Americans' first real image of a young gay man overcoming addiction. He calls those months of fishbowl living his "halfway house": "Everything seemed to happen for a reason. Talking to people--it became my life."

Three years later he lives on New York's Long Island, focusing on his painting and touring high schools and colleges to talk about addiction and recovery. As part of that work he wrote the just-published Clean: A New Generation in Recovery Speaks Out (Hazelden, $12.95), a combination of autobiography, self-help, resource, and stories from other former addicts.

Alcoholism was Beckman's most enduring battle, begun at a young age, but he eventually also fell in thrall to crystal meth. "I know when I tried it, my immediate reaction was to get more," he says. "[I thought,] This is really great! For a while there, it really controlled my life."

It also gripped the life of an addict named Charlie from Knoxville, Tenn. He and other addicts tell their own stories in separate short passages offered throughout Beckman's narrative. Charlie says bluntly, "Methamphetamine is a drug of the devil--I wouldn't wish it on anyone. Staying up for 100-plus hours while having 'fun' eventually yields an addiction that will remain with you forever."

Beckman also writes of his own meth binges. He once stayed up for 36 hours straight to paint a friend's new apartment (finally collapsing facedown in an ashtray) and spent another two days creating canvas "masterpieces." All the work that looked brilliant while he was high turned out to be nothing but ugly messes once he crashed.

"I can laugh at those stories now," he says. "But it's insane behavior. To look at it with the clarity I have now, I can't help thinking, Did I do that? I'm lucky to be alive."

Beckman's story is sadly typical: Growing up in Massachusetts, he started using alcohol at age 11, quickly moved on to pot and mushrooms, and in college regularly used drugs like cocaine, Special K, and ecstasy. He first tried crystal meth at age 18, he says, and he was hooked. He also speaks frankly about being molested by a priest, and about his father, who Beckman says also struggles with addiction. In high school, Beckman says, he was so closeted that he gay-bashed another boy so no one would think he was queer, and he cozied up to a girl who had access to good pot.

He also admits to using his good looks to feed his addictions. "Being good-looking," he says, "was never a burden. It certainly got me into clubs before I was of age."

Beckman eventually came to his senses. Not after getting drunk and landing a rental car in a ditch, or after assaulting a police officer, or on hundreds of other occasions when he might have recognized his destructive behavior. In fact, he says, he used his battle with crystal to prolong his alcoholism. "I thought I was sober when I stopped using illegal drugs. I [still] needed to drink. I held on to it because it was what my friends were doing. I could be social. That lasted for a few months."

Then came his simple epiphany: While drunk, he brought a stranger home, and suddenly he realized his behavior was dangerous and stupid and wondered what he was doing with his life.

Beckman describes getting truly clean for the first time at 23 and feeling like he was emotionally much younger--not unlike some gay people who come out at 19 or 25 and feel they've been cheated of a typical adolescence: holding hands, taking a date they care about to the prom, enjoying a first kiss that doesn't lead inevitably to sex.

"It is almost the same," says Beckman. "It isn't fair. I've wondered, Why are some gay people so promiscuous? Why is that a problem? I think as time goes on there will be less of that. [Gay] adolescents will be able to experience those things."

Beckman tells his story without blaming his addiction on any of the experiences in his life that are so often linked to substance abuse: living in the closet, being sexually abused, coming from a family with a history of addiction, living in poor neighborhoods, and so forth. Nor does he credit his recovery to his blessings: good looks, artistic talent,

intelligence, and a network of supportive family members and friends who care for him. Rather, he takes personal responsibility for both his substance abuse and his recovery.

"The truth is, addiction can happen anywhere, anyplace, anytime," he says.

And so can recovery.