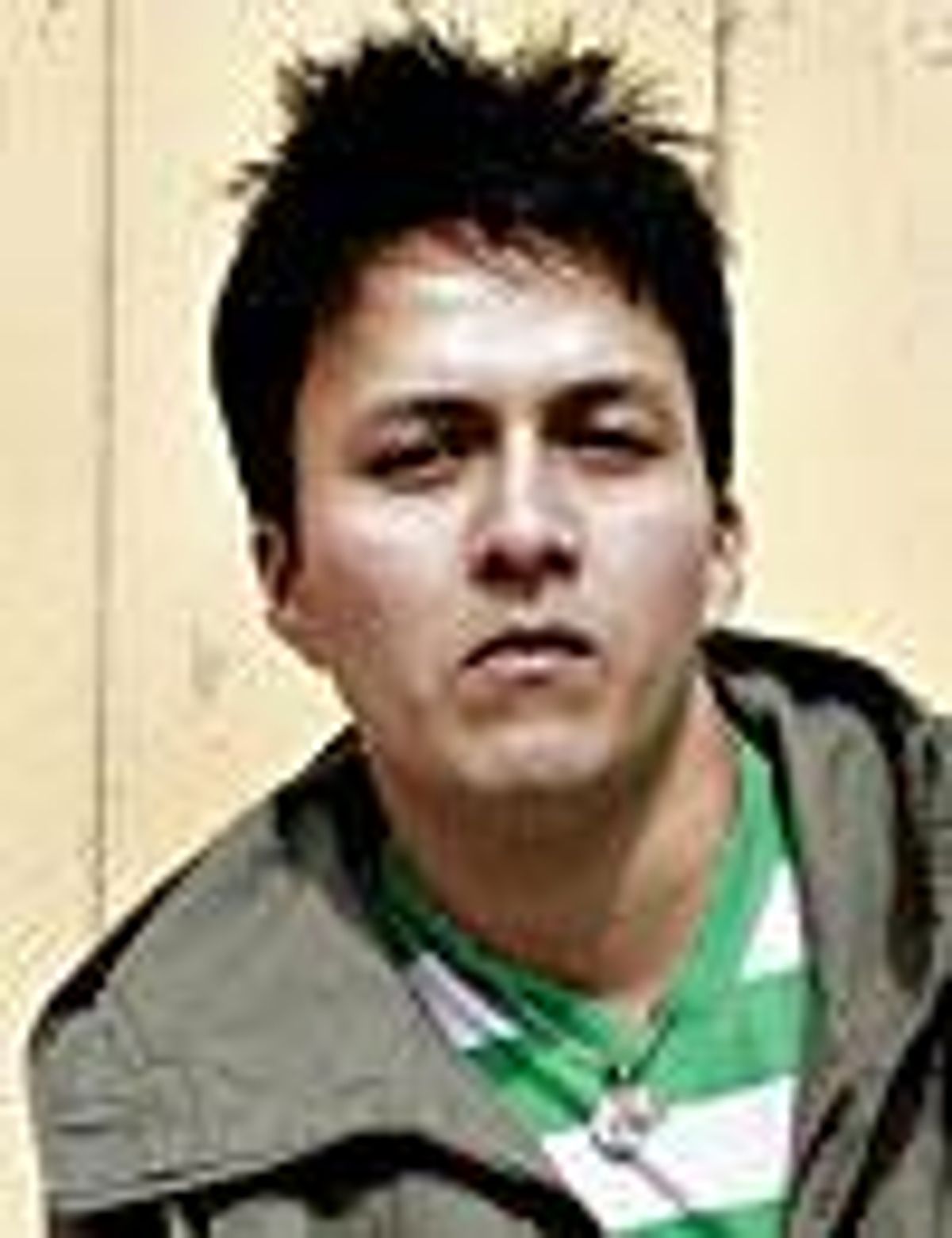

In a cramped

downtown Toronto office, Alvaro Orozco sits across from his

lawyer, El-Farouk Khaki. The doe-eyed Orozco, a native of

Nicaragua who at 21 could easily be mistaken for a

teenager, smiles as he shows off the medal he just

received for participating in the five-kilometer run at

April's North America OutGames in Calgary. Orozco has

also brought back a gift for Khaki, a piece of

amethyst crystal the young man says will bring

"good energy."

Without his own

remarkable energy, Orozco might not be in Canada--or

anywhere. Raised by an alcoholic father who beat him daily

for being gay, Orozco ran away from his home and

family in Managua, Nicaragua's capital, in

1998, just before he turned 13. He hitchhiked up the

Pan-American Highway through four countries and swam

the Rio Grande river into Texas. Once in the United

States, Orozco was held in detention centers in Texas

and then bounced from Dallas to Miami to Buffalo until he

reached Toronto in January 2005. There he filed for

asylum on the grounds that he would be persecuted for

being gay if he had to return to Nicaragua.

But in October

2005 a member of Canada's Immigration and Refugee

Board--an official of one of the most liberal

governments in the world--rejected

Orozco's asylum claim because she did not believe he

is gay. Such a denouement may seem implausible,

especially given the arduous life of Orozco, who was

20 at the time. But for countless gay and lesbian asylum

seekers worldwide, it's all too ordinary.

"I was

stunned by the decision," says Khaki, who did not

represent Orozco at the time but has since gotten his

deportation, originally scheduled for February 2007,

postponed until August while an appeal is prepared.

Many in the

Canadian media are echoing Khaki's questions about

the ruling and the reasoning behind it. There's

a precedent for granting asylum on the basis of sexual

orientation in Canada as well as in the United States

and other countries. However, in making her decision, the

immigration official, Deborah Lamont, cited the fact

that Orozco had not been sexually active with other

men--as if sexual activity were the only

"proof" of his gay orientation.

"If you

are straight and you don't have sex--are you

any less straight?" Khaki asks. "Some of

the questions he was asked during the refugee hearing

were just inappropriate. How can you ask a 20-year-old why

he hasn't been sexually active since the age of

12?"

Unfortunately,

Orozco's prior team of public defenders was not

equipped to argue his case before Lamont--who,

to make matters worse, conducted the hearing by

videoconference from her office in Calgary. It wasn't

until February 2007, when the young man was about to

be deported, that Khaki, a well-known gay Muslim

activist, came aboard. With his help, Orozco may just

manage to stop running at last.

Why can't

Orozco go back to Nicaragua? The answer reads like a

suspense novel. Born in 1985, Alvaro knew at 7 that he

was gay. His father--who regularly beat the

child's mother--realized it too. So he started

beating the boy in hopes of making him straight.

"If...any one of you is a f****t, I will

kill you with my own hands," Orozco recalls his

father telling him and his four brothers.

"On

TV," he adds, "I saw that it was illegal in my

country to be gay." In 1992, Nicaragua amended

its penal code to make homosexuality punishable by up

to four years in prison.

As Orozco goes

on, he begins to stutter. It happens every time he talks

about these things. "I was so scared," he

says. "I remember going to church--my

family is Catholic--and many times I heard the priest

say that gay people will go to hell. It was then I

knew I had to leave, that I couldn't grow up

here. I couldn't wait until I was 18."

He ran away, even

though his friends thought he was crazy to do so. "I

was in military school," he says, "and my

favorite subjects were history and geography. So I

took a few maps out of one of my geography books and

mapped out my trip."

He hitchhiked his

way through Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and

Mexico. At each stop he would go to the local church and

tell them the story of the violence he suffered at the

hands of his father. Members of the church would give

him shelter, feed him, and help him find odd jobs. He

never mentioned his sexual orientation for fear that the

good church people would turn their backs on him.

Orozco swam

across the Rio Grande and set foot on American soil in 2000

in Texas, where he was picked up by U.S. immigration

officials and thrown into a detention center for

illegal alien minors in Brownsville. He was 14 and

spoke no English.

Soon Orozco was

transferred to a facility for homeless and immigrant

minors in Houston run by Catholic Charities. Officials there

told him that the U.S. government did not want illegal

minors to become citizens. Orozco met with an

immigration officer who even threatened to sabotage

any asylum claim. So he escaped from the facility and landed

in Dallas, where he lived with a Nicaraguan family for

a year, working odd jobs in gardening and

construction, and at a lamp factory. He also joined a

church-affiliated Boy Scout troop.

It seemed as if

Orozco was finally starting a life of his own. But on

learning that authorities in Texas were aggressively going

after illegal immigrants--it was after 9/11 by

then--he decided he'd do better in a city

with a larger Latino population. While on a trip to Disney

World in Orlando, Fla., with his Scout troop, Orozco

slipped away and took a bus south to Miami.

During his five

years in the United States, he had tried without success

to get a lawyer to take his case. To make matters worse, he

was so used to hiding his sexual orientation, he never

told anyone he was gay. He didn't realize that

his case might have been stronger if he had mentioned

the violence he'd suffered because he was gay.

In the end, it

was Canada, not the United States, that captured

Orozco's imagination. On the Internet he found

information about Canada's immigration laws and

gay-friendly political environment. He took a bus from

Miami to Buffalo, N.Y. With the help of Buffalo-based Vive,

an interfaith group at the Canadian border that helps

refugees from around the world, and its shelter, La

Casa, he settled in Toronto.

In those

cosmopolitan environs, Orozco began living as an openly gay

man for the first time. He made gay friends; he joined

a gay church. He enjoyed freedom he could never have

imagined back in Nicaragua.

Then in October

2005 the refugee board rejected his asylum claim, and

everything changed again. "I found the claimant left

Nicaragua in order to secure a better future for

himself elsewhere and fabricated the sexual

orientation component to support a nonexistent claim for

protection in Canada after having already been

rejected in the United States of America for his past

dysfunctional family life," Lamont wrote in her

ruling.

"As a

result, I found the claimant could return to Managua, find a

place to live away from his abusive father, and that

there is no more than a mere possibility the claimant

would be persecuted there."

Orozco's

first reaction was visceral. "I was scared,"

he says, his stutter worsening. "I remember

what happened back home. It's not easy for me,

thinking about my father. I can't imagine going back

there. And I didn't understand why [Lamont]

didn't believe I am gay."

A February 2007

editorial in the Ottawa Citizen, the daily newspaper in

Canada's capital city, questioned the board's

conclusions. "The question to ask Alvaro Orozco

is not whether he's had romances with men," it

read. "The question is whether he'll face

persecution as a homosexual if he returns to

Nicaragua.... There may indeed be valid reasons for

Canada to turn down this application. But it is

unreasonable to demand proof of love life from young

people who ask for asylum based on sexual

orientation."

El-Farouk Khaki,

43, is not what one might expect. His practice is housed

in a dingy office building atop a pizza joint on the

outskirts of Toronto's gay neighborhood. On the

day of this interview, his purple-and-black plaid

jacket is paired with black leather pants. He wears

multiple rings and earrings--and a goth-looking

black-and-silver wristband.

Born in Tanzania,

Khaki was 7 when his family had to flee because his

father became a target of the dictatorial government. Their

displacement--first to London, then to Vancouver,

Canada, where he eventually went to law

school--makes him unusually sympathetic to a

clientele dominated by gay and lesbian asylum seekers.

"My own

journey was that of a person of color, an immigrant, and a

Muslim," Khaki says. "Then by coming out, I

became a minority within a minority." But, he

adds, "I'm still privileged in many ways, so

it is my responsibility to use that privilege to open

doors for others."

Orozco's

case, he says, is typical. "It is a common experience

of many of my clients, especially around

Alvaro's age. Not only do they suffer societal

violence but rampant violence in the home."

Khaki is

preparing three lines of appeal. On one front, he's

asking the board to reopen the case based on the

board's failure to recognize Orozco as a

vulnerable claimant. On another, he hopes to show that

Orozco has already established himself in Canada and

that removing him would cause undue hardship. Lastly,

a Pre-Removal Risk Assessment will be filed to show

the risk involved in sending Orozco back to Nicaragua.

"Hopefully," Khaki says, "one of these

will be successful" so that Orozco will be able

to stay in Canada.

According to The

[Toronto] Globe and Mail, of the 228 Nicaraguans who

sought refugee status in Canada from 2002 to 2006, 35 were

approved. It's not known how many of those

claims were based on sexual orientation, but the paper

notes at least two of those granted asylum--Managua

activist Yader Manzanares and his partner--are

gay.

"Canada

recognizes persecution based upon sexual orientation, so we

haven't seen many cases being refused on that

basis," says Gloria Nafziger, refugee

coordinator at Amnesty International Canada. She adds

that Nicaragua's law criminalizing

homosexuality--even if Amnesty doesn't

know of anyone charged under it--"creates a

climate that allows for the persecution of gays and

lesbians and makes it more difficult to seek help from

the police when you're in danger."

For now, Orozco

is attending counseling sessions mandated by the board.

("They fail to appreciate that the effects of

physical and emotional violence are not rectified in a

few months' time," Khaki says ruefully.)

Orozco continues to work, meet new people through community

organizations, and even date. Meanwhile, August 9, his

current deportation date, approaches.

The question that

looms in everyone's minds is what will happen to him

if he is sent back. After all, Khaki and Orozco note,

the Canadian media coverage of Orozco's case

has been translated and published back in Nicaragua, a

new element of risk that did not exist when he first filed

an asylum claim.

Walking down

Yonge Street, Toronto's main thoroughfare, Orozco

watches the crowds on a busy weekday afternoon.

"I love Toronto," he says. "It's

so diverse here. So many different people from different

places, and no one cares. There's so much

tolerance here, even compared to the United

States."