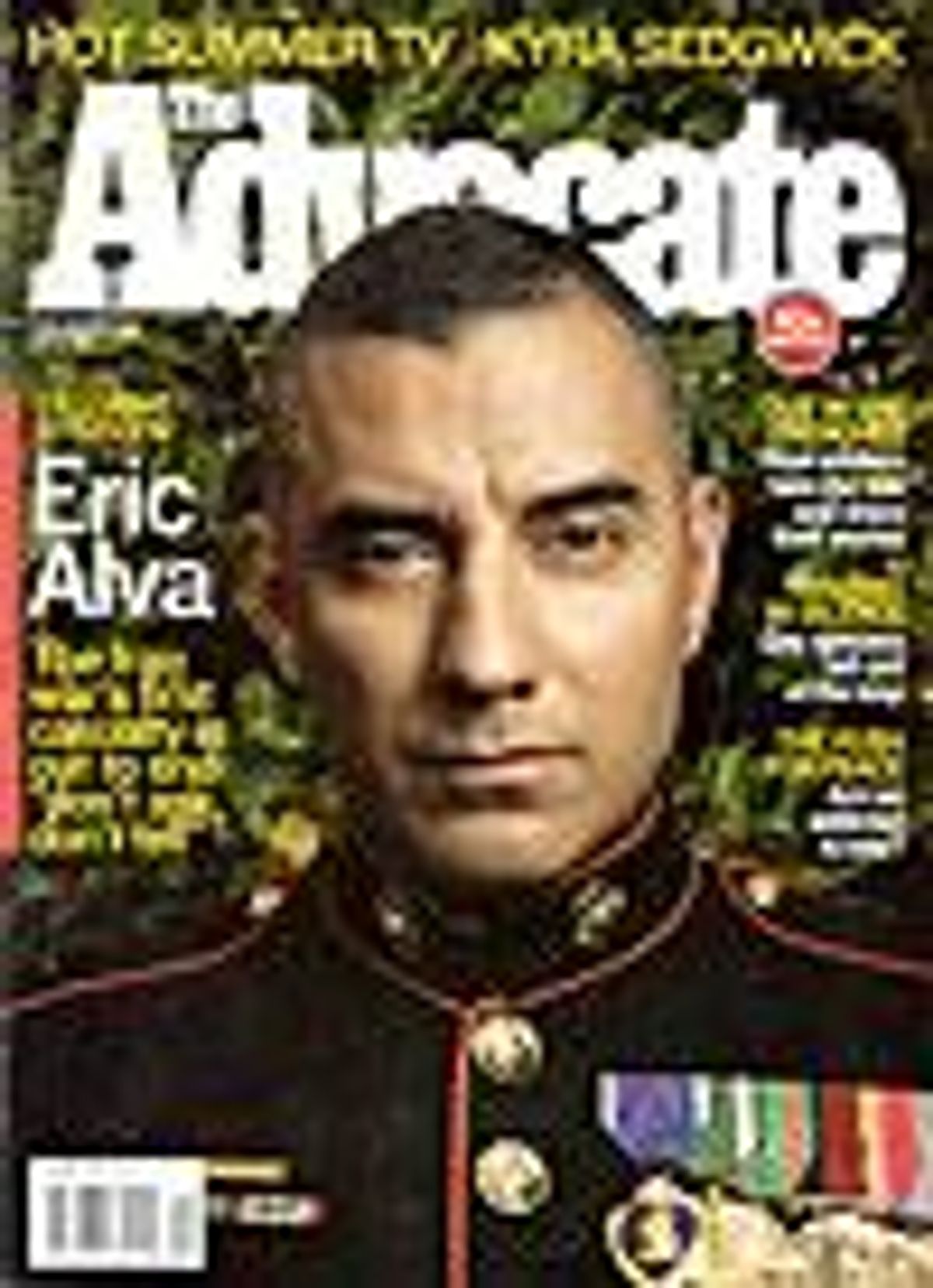

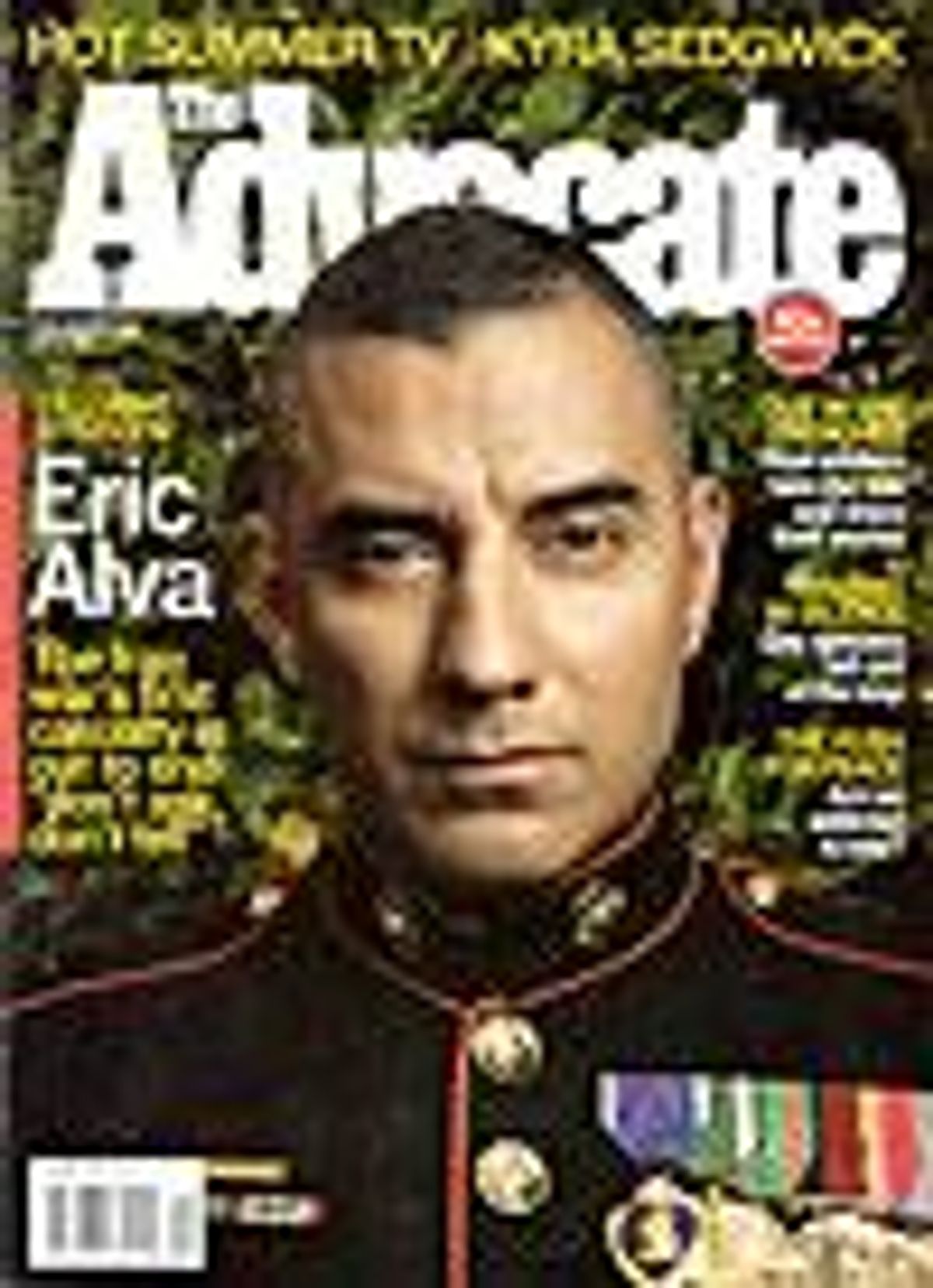

The gay marine staff sergeant lost a leg fighting one enemy. Now he's taking on another--the U.S. military's antigay policy.

June 15 2007 12:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The gay marine staff sergeant lost a leg fighting one enemy. Now he's taking on another--the U.S. military's antigay policy.

On the night of March 20, 2003, Lois Alva tossed fitfully in her sleep at home in San Antonio. In a dream, she saw her son Eric speeding across a vast expanse of sun-whitened desert in a Jeep.

"In the dream," she recalls, "his leg was sticking out the window of a vehicle." Lois woke with a start, profoundly chilled by the surreal image, particularly on this night. After months of bellicose chest-pounding from the White House about weapons of mass destruction, terrorism, and Iraqi freedom, the invasion of Baghdad was under way, and Eric's Marine battalion was part of the first wave.

The next day Staff Sgt. Eric Alva would step on a land mine that would shatter his right arm, rip his leg from his body, and make him the first casualty of the Iraq War.

"Welcome to Texas," says 36-year-old Eric Alva in the faintest drawl as I approach him in the San Antonio International Airport. He's fit, tan, and dressed in cargo shorts and a T-shirt. And within seconds he's in motion, enthusiastically taking my bags from my hands and wrangling my luggage into his car with as much dexterity as any man on two legs.

"Hey, Alva!" shouts the parking lot attendant through the glass partition. "I saw you on TV again. Keep up the good work, man. We're all proud of you." Blushing furiously, Alva graciously thanks the woman, then aims his beige Nissan Pathfinder into traffic, heading for the house he shares with his partner, Darrell Parsons.

Behind the wheel, Alva drives like a marine. He squints fiercely into the late-afternoon sunlight, his jaw set in a firm line. He may be retired, but military bearing is his default condition. "I grew up here and people know me," he says modestly in response to a question about the attendant. The consummate team player, Alva is always reluctant to be seen as more heroic than any other marine.

But Alva isn't like every other marine. In 2003, with the invasion still fresh in the minds of more optimistic Americans, the newly wounded marine was a symbol of everything noble and patriotic about the U.S. military. He was awarded the Purple Heart by Gen. William Nyland, the former assistant commandant of the Marine Corps. He was photographed with the president and first lady as well as Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sheryl Crow. Donald Rumsfeld dropped by his hospital room for a photo op. The picture shows the former secretary of Defense towering over the frail, stone-faced marine and grinning like a great white shark.

Four years later, Alva once again distinguished himself--by coming out on Good Morning America and speaking against the military's ruinous "don't ask, don't tell" policy.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered