All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

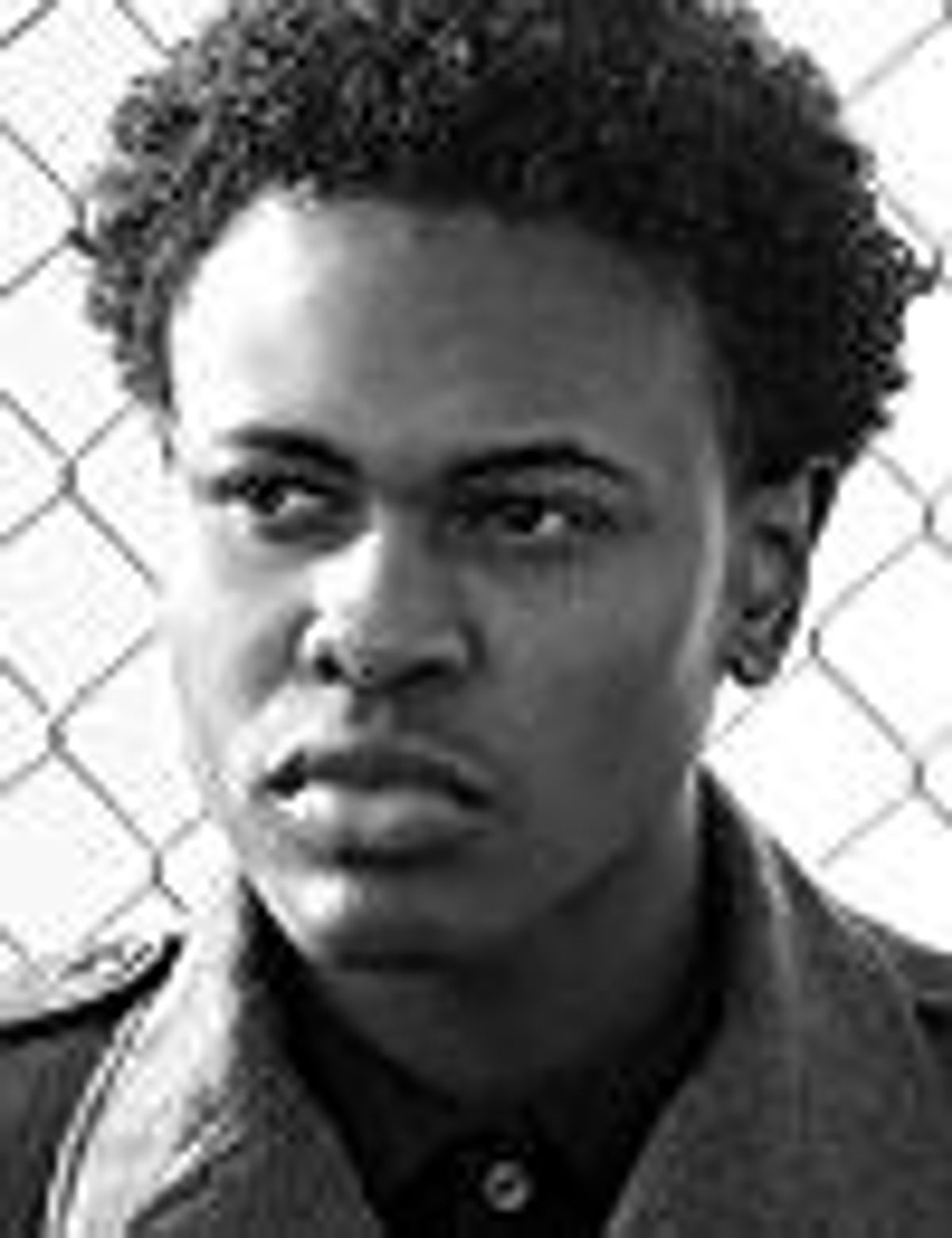

Iwas on the A train, heading uptown around 3 a.m. one night this past June when a New York Police Department officer grabbed my arm and forced me off the subway. Officer Nunez and his colleagues promptly interrogated me about where I was going and why was I out so late.

After answering their questions, I asked why I was removed from the train. I was told it was because I was asleep. But I wasn't sleeping, I replied--I was resting my head on my arm because I was tired and didn't feel well. Nunez didn't listen. Instead, he asked why my cell phone number didn't have a New York City area code, why I live in Washington Heights [an upper Manhattan neighborhood], and other questions that were irrelevant to the situation. Then he did a warrant check on me. As I stood waiting for the result, with my arms crossed and rolling my eyes, I noticed the other officers were laughing at me and making comments under their breath.

Finally, Nunez issued me a citation for occupying two seats--even though there had been only five other passengers on the train, some of whom had also occupied two seats. I wasn't preventing anyone from sitting, so I wasn't in violation of any transit regulations. Yet I still got a ticket.

Trending stories

The incident reminded me of my prior dealing with the NYPD, during the winter of 2005, when I was drugged, abducted, and sexually assaulted by a stranger at a club. After going to the hospital and taking medication to prevent HIV infection, I decided to press charges. The medicine made me feel ill, so telling my story to officers from a special victims unit in Harlem was tough. Unfortunately, the officers became rude and impatient when my memory faltered--my drink had been drugged, so the details of what happened were hazy, but they didn't seem to understand that.

I decided to investigate on my own. I returned to the club, where a bartender helped jog my memory. Then I retrieved a license plate number and eventually even located my assailant--but the police still took no action. At one point the officers actually accused me of wanting to get free medication, because the sex was unprotected and I was afraid of being infected with HIV. I was appalled by this discriminatory treatment, but I didn't report it. I was too embarrassed to come forward. The police made me feel like I was less than a man.

Today, I ask myself why the NYPD couldn't enforce sexual assault laws to the same degree that they enforce transit laws. In the subway I was accused of breaking a law that in reality I hadn't broken. The person who assaulted me, however, actually broke the law but hasn't ever been brought in for questioning. Based on the facts of both cases, I can't help but conclude that things turned out badly for me because I am a young black gay man.

Law enforcement officers need to realize that they are working to protect all people, not just a specific demographic. I never thought I would have to disclose the details of my life like this, but it needs to be done to stop the injustice that we as young black gay men face in New York City. It hurts me to think that preventing people from sleeping on the train is more important to the NYPD than bringing a rapist to justice.