It still pains Pearl Ricks to think about how they almost made history.

The gender non-conforming, intersex community organizer ran to represent Louisiana’s House District 23 last fall. If elected, they would have been the state’s first out LGBTQ+ legislator to hold office.

Ricks, a progressive, tried to appeal to the district’s majority-minority, liberal swath of New Orleans residents with a tagline of “speaking truth to power” and a platform built on expanding abortion and gender-affirming healthcare access. But when primaries happened in October, Ricks came in third by 400 votes and didn’t qualify for the general election.

“It hurt to get so close,” Ricks said.

They aren’t alone. LGBTQ+ candidates have campaigned for seats in Louisiana’s state legislature for decades. And despite a growing number of out candidates winning office nationwide, the state’s residents have never elected one.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

As lawmakers prepare to gavel into regular session in Baton Rouge on March 11, they remain the only legislative body of all 50 states to have never had an out queer person in office. It earned the distinction late last year, after the only other state without a queer legislator, Mississippi, elected an out gay man to its House of Representatives.

Louisiana’s vacuum of queer legislators comes amid a nationwide surge in anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Republican-majority legislatures have introduced the bulk of bills, which target everything from transgender adults’ rights to access public restrooms to bans on gender-affirming healthcare for minors. National rights organizations have declared states of emergency amid the rise.

Louisiana lawmakers passed their own ban on care for transgender minors last year. Advocates fear 2024 could bring more extreme legislation. Republican lawmakers have already preliminarily filed several anti-LGBTQ bills ahead of the start of the legislative session. One proposal would bar public school teachers from discussing sexual orientation or gender identity in class. A separate bill would require parent permission for students to change their name or pronouns at school.

A third law seeks to narrowly define the terms male and female in state law based on “biologically based definitions of sex.” Republicans in other states, including Utah, have passed similar laws, which in effect ban transgender people from using public restrooms.

Louisiana’s new far-right governor, Jeff Landry, is expected to sign the legislation. Landry has called gender affirming care for minors “sexual abuse” and advocated for state investigations into residents who seek care — even in states where it’s legal.

The dearth of LGBTQ+ lawmakers has left queer Louisianans, which make up 3.9 percent of the population, vulnerable to losing more rights, said Stephen Handwerk, a political consultant and former head of the state’s Democratic Party.

“We don't have anybody in the room where all of the decisions are getting made about our lives, about our livelihood, about our families,” said Handwerk, a gay man who recently fled the state because he felt unsafe in his hometown of Lafayette, La.

Candidates for the legislature, Handwerk said, face a number of headwinds when trying to break through, including anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment among a large percentage of Louisiana voters, under-investment in LGBTQ+ candidates, long term limits and old guard party politics.

As a political newcomer, Ricks said they struggled to get support from the Louisiana Democratic Party, which endorsed their opponent. National organizations such as the Human Rights Campaign, which work to elect out candidates, were also slow to donate and publicly endorse them, Ricks said. (Neither the Democratic Party nor HRC responded to a request for comment for this story).

Ricks wasn’t able to afford a campaign manager. Instead, they took out over $10,000 in personal loans to employ a finance manager and a fundraiser. They relied on friends and volunteers to help knock on doors.

Courtesy Pearl Ricks

Courtesy Pearl Ricks

Despite their scrappy operation, Ricks managed to win more than 21 percent of the vote in a primary race with three other Democrats. But it wasn’t enough to make it on the ballot in November.

“I still feel as though I was the best candidate in my race,” Ricks said. “But I was nowhere near the best resourced.”

Other former LGBTQ+ candidates and political analysts in Louisiana point to a weak state Democratic Party as a major barrier to electing an out state legislator. The party spent a fraction of what its Republican counterpart did in supporting legislative candidates in 2023, according to campaign finance records.

More than 90 percent of LGBTQ+ candidates nationwide are Democrats, according to the LGBTQ+ Victory Institute, which tracks and endorses out public officials. That puts a lot of power in the hands of the state’s current Democratic Party leadership, said Sean Meloy, the Victory Institute’s vice president of political programs.

“There’s a lot of machine politics in Louisiana,” Meloy said. “It’s possible to break through that, and I think that in a lot of places around the country our candidates have, but in Louisiana we just haven't been able to get there.”

Despite its distinction of never having an out state legislator, some Louisiana candidates and public officials see opportunities to improve representation. A grassroots campaign called Blue Reboot is working to get more than 100 Democrats elected to local party administrative seats, which vote on statewide party leadership roles.

A “large percentage” of candidates are openly queer and hope to run for state office one day, said Mel Manuel, a Blue Reboot member and current Democratic candidate for Louisiana’s 1st Congressional District.

“I think we need to reform the party before we can talk about getting an openly queer person elected to the legislature,” Manuel said.

For some LGBTQ+ candidates, fear of acceptance among the state’s conservative, religious voters is another major barrier to running for office. Conservative Catholic and Baptist voters make up a large share of Louisiana’s population. That stopped Brittany Gondolfi from talking about her queer identity on the campaign trail when she ran for state Senate District 12 last fall.

Gondolfi, a children’s book author and recent law school graduate, ran on an abortion rights platform against her Republican opponent. Her stance on that issue alone drew death threats. One voter from her rural district commented “baby killer” on one of her Instagram posts.

“I wish I had more courage to talk about my queer identity, but the abortion thing literally took it all out of me,” she said.

Gondolfi, too, struggled to get support from the state Democratic Party or its local chapter, she said. While speaking publicly about her progressive policy ideas, she felt isolated from conservative family members and friends.

“For queer candidates in the South, you are not just coming out to the world. You're coming out to everyone you know,” she said. “And a significant portion of the population believes that God condemns gay people to hell.”

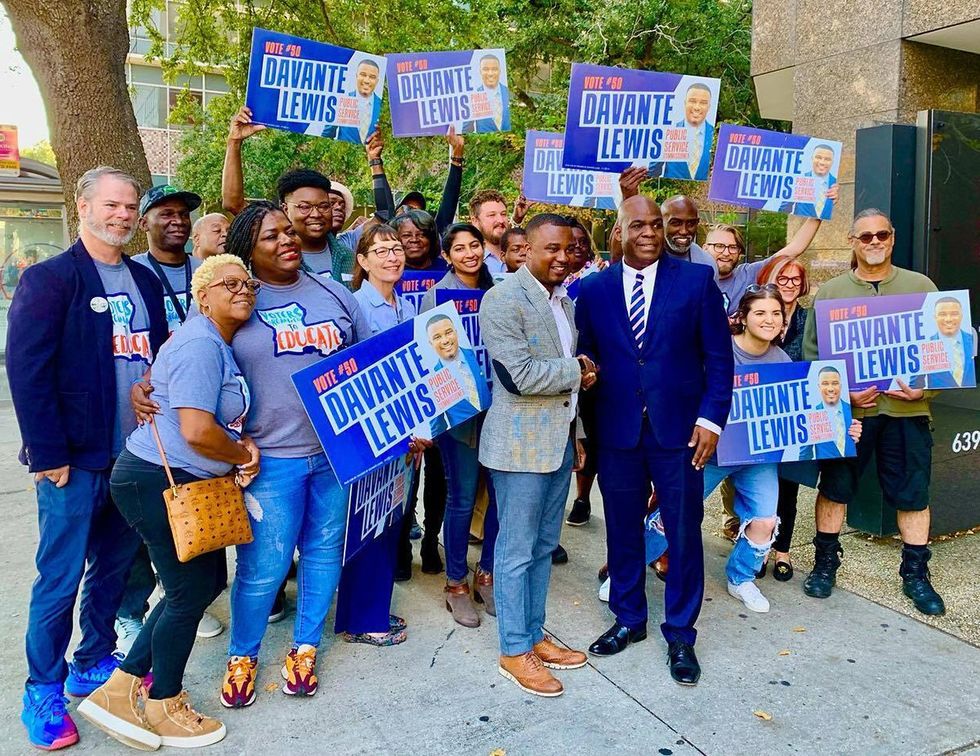

Courtesy Davante Lewis

Courtesy Davante Lewis

Louisianans have supported out LGBTQ+ candidates to state offices outside the legislature, though. In December 2022, voters elected Davante Lewis to the Louisiana Public Service Commision, the state’s utilities regulator.

Lewis, a gay man, is now serving as the first out, elected LGBTQ+ state official. He described his campaign platform as “monolithic,” and focused on keeping residents’ energy bills as low as possible.

“Everybody wants their power to come on,” Lewis said. “There’s no gay or straight way to have a cheap utility bill.”

Still, his success is a lesson for other LGBTQ+ candidates hoping to win elections in Louisiana office, he said.

“You can run out and open and honestly, but then also focus on what people care about,” he said. “You can break through the noise.”

Shutterstock

Shutterstock Courtesy Pearl Ricks

Courtesy Pearl Ricks Courtesy Davante Lewis

Courtesy Davante Lewis

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes