CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Last year 106.5 million people gathered around the television to watch the New Orleans Saints beat the Indianapolis Colts 31-17 in the Super Bowl. While most are there for the game and some wings, catching the high-priced Super Bowl ads is inescapable. No other event celebrates American capitalism so effectively: The top companies in the country, if not the world, fork over an average of $3 million (on top of production costs) to air a 30-second ad, hoping to capture the attention of one third of the U.S. population. While this is a chance for advertisers to show their best work, should it be at the expense of making gay people a punch line?

"Sometimes advertisers present images that cast LGBT people -- and in the case of Super Bowl ads, usually gay men -- in an unfair light," says Jarrett Barrios, president of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. "Usually those images are rooted in tired stereotypes that perpetuate misconceptions about our community and in some cases have even promoted violence against LGBT or LGBT-perceived people."

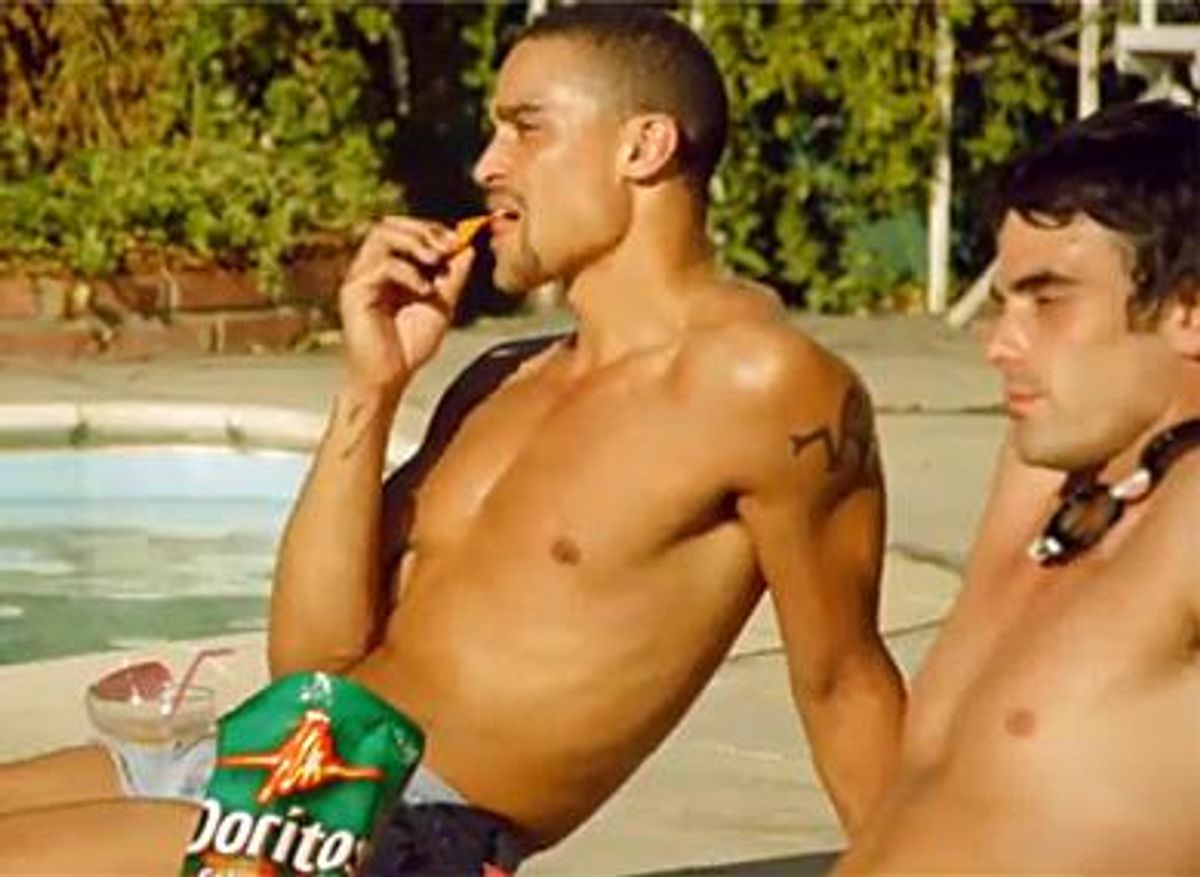

Take, for instance, two user-generated spots pitched by fans for Doritos' "Crash the Super Bowl" contest that made the rounds on the Internet last month. After varied public reaction (some people found the overtly gay characters and messages a bit too stereotypical; others said they were simply funny), Frito-Lay director of public relations Chris Kuechenmeister said the ads weren't in the running to air on television. While the spots used stereotypical gay characters or the old "sex-starved in the sauna" scenario, it seems as though they were meant to be a wink and a nod toward gay people, but it didn't quite work out.

Mike Wilke, an advertising consultant and founder of the Commercial Closet Association (which has since been absorbed by GLAAD), says male-driven advertising has shown evidence of a slight change in attitudes among ad directors in recent years.

"I think there isn't as much evolution across the board as there could be as far as a changing audience," he says. "But it does seem that there is an appreciation for the fact that homophobia exists."

While Ikea ads of two dads picking out a crib for their baby likely won't be airing during the big game, Wilke did recall a Pepsi spot that featured an attractive man strutting down the street, unabashedly catching the attention of every man and woman he passed.

On the contrary, Wilke also remembers an ad for Bridgestone tires that showed a driver trying to run down flamboyant fitness icon Richard Simmons (who is not openly gay).

"Things are still a mixed bag," he says of the ad. "What was a surprise to me was that the director of advertising at Bridgestone had spent years attracting gay media, including advertising for years in The Advocate. In this case, it seems like it wasn't a matter of intentional homophobia, but a matter of accident, and a mixed review within the gay community of whether it was an acceptable message."

It may be a mixed bag because of where we are as a society. When it comes to gay rights, America has a patchwork of accomplishments: some states have legalized same-sex marriage, domestic partnerships, or civil unions, while others attempt to prevent any recognition of gay couples. The repeal of "don't ask, don't tell" is a major victory, but civilian LGBT workers in many states can still lose their jobs because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. And as some states -- and the federal government -- attempt to enact laws to keep gay youths safe in schools, the messages young people see in the media may be what influence them the most.

"Several television shows not only feature LGBT characters, but also feature images that reflect the rich diversity of our community, including representations of gay men who fall on what is traditionally considered the more 'masculine' end of the gender spectrum," says Barrios. "From the CW's 90210 to Calvin, the young African-American gay frat brother on ABC Family's Greek, the entertainment industry is presenting images that break the mold and help Americans understand that LGBT people are just like them. Advertisers are falling well below that curve and missing an opportunity to demonstrate their support for full equality and fully engage LGBT consumers."

But still, those influences are mainly missing when the Super Bowl comes around. If anything, says Stony Brook University sociology professor Michael Kimmel, advertisers right now are targeting the downtrodden, down-on-his-luck, white American male. In commercials like last year's Dodge Charger ad, an announcer lists the day-to-day sacrifices he makes (carrying his wife or girlfriend's lip balm, listening to her friends talk about why they don't like his friends, and taking out the recycling), all of which compromise his masculinity, therefore allowing him to choose the car he drives.

"What's interesting about this ad is the assumption that they're married," Kimmel says. "Is carrying her lip balm so humiliating? Is that the worst we can feel?"

As gay people have become more accepted in mainstream society thanks to new laws, changing attitudes, and a more perceptive group of media professionals, advertising is still catching up. As Barrios points out, some of the top television shows, including Glee, Modern Family, and True Blood, feature gay characters who add dimension to the shows, without compromising ratings or critical acclaim. Meanwhile, in between plays, a Super Bowl viewer will see a Snickers ad where the punch line is two men being completely grossed out because they accidentally kissed, or another Dodge commercial where a butch guy calls a male pixie a "silly little fairy." Tinker Bell retaliates by turning him into a sweater-clad metrosexual.

Wilke says, "I think the everyday straight male image is constantly evolving. We're in a place where advertising tries to reflect society, though it's much slower than TV and film than being anything close to reality -- not that advertising tries to be real. In regards to showing greater diversity in types of character, we're starting to see more sensitive guys, even while still seeing the classic macho guy."

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

31 Period Films of Lesbians and Bi Women in Love That Will Take You Back

December 09 2024 1:00 PM

18 of the most batsh*t things N.C. Republican governor candidate Mark Robinson has said

October 30 2024 11:06 AM

True

After 20 years, and after tonight, Obama will no longer be the Democrats' top star

August 20 2024 12:28 PM

Trump ally Laura Loomer goes after Lindsey Graham: ‘We all know you’re gay’

September 13 2024 2:28 PM

Melania Trump cashed six-figure check to speak to gay Republicans at Mar-a-Lago

August 16 2024 5:57 PM

Latest Stories

Gay arts and entertainment journalist Gil Kaan has died at 72

December 23 2024 6:19 PM

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signs new law protecting LGBTQ+ students from being outed

December 23 2024 5:14 PM

Get ready for Aspen Gay Ski Week 2025

December 23 2024 4:24 PM

Donald Trump promises transphobic policies that will target youth and service members on 'day one'

December 23 2024 12:28 PM

Matt Gaetz allegedly paid tens of thousands of dollars for sex and drugs: House Ethics report

December 23 2024 10:41 AM

Freemasons, gay men, and corrupt elites in Cameroon — inside a conspiracy theory

December 21 2024 12:51 PM

Kathy Hochul vetos financial protection bill introduced after murders of gay men

December 21 2024 12:29 PM

35 pics of celebs uniting at David Barton & Susanne Bartsch Toy Drive 2024

December 20 2024 5:01 PM

From Saturnalia to Santa, is Christmas just drag in disguise?

December 20 2024 4:44 PM

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered