Religion

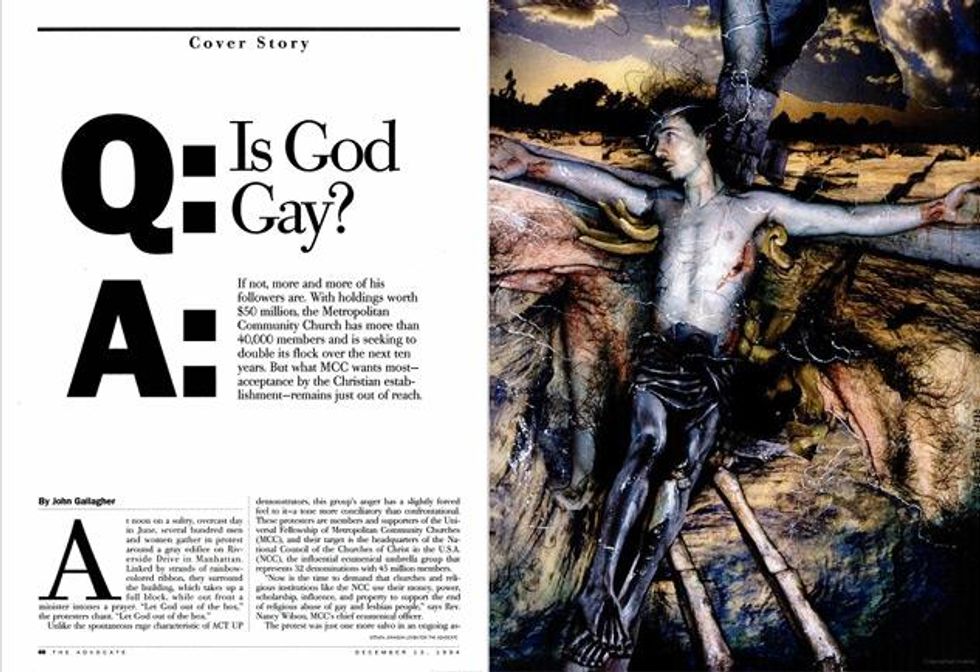

When The Advocate's 'God Is Gay' Cover Infuriated the World

When The Advocate's 'God Is Gay' Cover Infuriated the World

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

When The Advocate's 'God Is Gay' Cover Infuriated the World

When The Advocate's 'God Is Gay' Cover Infuriated the World

The Metropolitan Community Church has been shaking up religion since its founding in 1968 as a Christian denomination especially for LGBT people. The Advocate covered the transformative MCC in a December 1994 cover story, and the editor in chief at the time, Jeff Yarbrough, inspired by polemic issues of Time and Rolling Stone, branded the cover with a very provocative title: "Is God Gay?" Reaction was swift:

"Advertisers pulled out," Yarbrough recalls. "My publisher screamed at me and told me someone had called in a death threat. Readers and a lot of nonreaders sent us hate mail. The straight press said we'd stepped over some imaginary line. I could sit here and say, 'Oh, I was shocked' by the reaction, but we were in the business of shock journalism and drawing attention to our fight; outing people, getting straight celebrities to admit to gay and/or lesbian dalliances, and calling out homophobes and roasting them for their narrow-mindedness and stupidity. So the 'Is God Gay?' cover and story was just another way to point out how marginalized we were at the time. I think it did its job. And I don't think Jesus would have minded us using him to convey a message of tolerance."

With Easter just around the corner, and all this talk of discrimination guised as religious freedom, we thought it a perfect time to resurrect our most famous cover story, which in actuality is quite tame. See for yourself:

Q: Is God Gay?

A: If not, more and more of his followers are. With holdings worth $50 million, the Metropolitan Community Church has more than 40,000 members and is seeking to double its flock over the next ten years. But what MCC wants most -- acceptance by the Christian establishment -- remains just out of reach.

At noon on a sultry, overcast day in June, several hundred men and women gather in protest around a gray edifice on Riverside Drive in Manhattan. Linked by strands of rainbow-colored ribbon, they surrounded the building, which takes up a full block, while out front a minister intones a prayer. "Let god out of the box," the protesters chant. "Let god out of the box."

Unlike the spontaneous rage characteristic of ACT UP demonstrators, this group's anger has a slightly forced feel to it -- a tone more conciliatory than confrontational. These protestors are members and supporters of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC), and their target is the headquarters of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA (NCC), the influential ecumenical umbrella group that represents 32 denominations with 45 million members.

"Now is the time to demand that churches and religious institutions like the NCC use their money, power, scholarship, influence, and property to support the end of religious abuse of gay and lesbian people." Says Rev. Nancy Wilson, MCC's chief ecumenical officer.

The protest was just one more salvo in an ongoing assault in which MCC, a denomination in its own right, has forced mainstream protest denominations to deal with gay issues.

"MCC put those issues on the agenda," says R. Stephen Warner, a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. "And now they won't go away, because MCC won't go away."

So far, however, despite plenty of debate, the mainstream denominations are far from arriving at any pro-gay consensus. While these groups bicker and waffle over how to treat their gay members and clergy, MCC has been growing by leaps and bounds.

"If you were to pick the ten fastest-growing denominations in the country, MCC would clearly be one of them," says Rev. Lyle Schaller, a nationally known consultant who advises parishes on growth and planning issues. "They are growing, while mainstream denominations are shrinking."

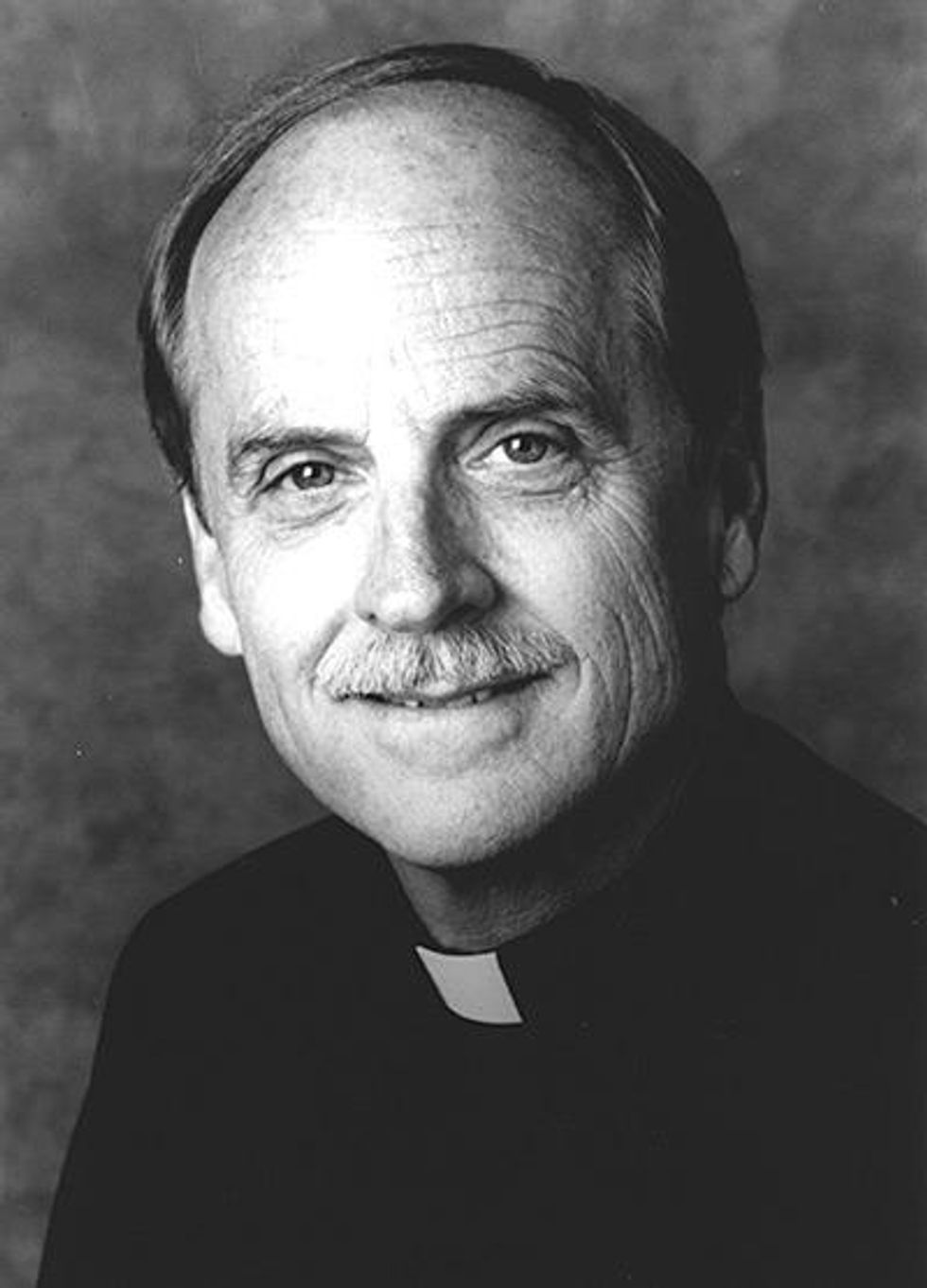

It has been 26 years since Rev. Troy Perry and 12 men and women celebrated their first MCC service in the minister's living room in Los Angeles, using a coffee table as an altar. In that time, the denomination has grown to 42,000 voting members and non-voting adherents in almost 300 churches in 16 countries. With contributions of $10 million annually and property holdings worth $50 million, MCC can claim to be the largest gay group in the United States, at least in financial terms.

"MCC is meeting the needs of a group that other denominations aren't meeting," Warner says of MCC's growth, though he adds that the explosion in its membership raises uncomfortable questions. "Is MCC siphoning off energies that might go into the Presbyterians or the Methodists? Does it serve as a safety valve to keep pressure down in those churches? In a sense MCC is doing a favor for protestant denominations in churching people others won't deal with. Somebody in those denominations can say, 'You've got your own church.'"

"We are not letting them off the hook," he says. Instead, he argues, MCC gives gay members of other denominations the support they need to "go back into their churches and push them to make a difference." But its role as a gadfly in no way compromises MCC's own bright future. "We're poised for growth," says Perry. "Our vision is to double in size in the next ten years."

One way to do that is to spend less time fretting over the issue of entry into NCC, as MCC has been doing since it first applied for membership in 1979. Two years ago NCC's general board voted 90 to 81 not to act on MCC's application for observer status, a position enjoyed by several Jewish and Muslim groups. The vote effectively squelched the issue. Though present at the annual convention of NCC's general board -- held in New Orleans in November -- MCC was not actively seeking membership or observer status.

"We were expending a lot of energy there," says Perry. "We have other ways of dealing with churches. We don't have to go through NCC."

Indeed, MCC belongs to National Interfaith Impact, a religious lobbying group in Washington, D.C., as well as the AIDS National Interfaith Network. Neither group, however, is as influential as NCC, membership in which symbolizes respect and acceptance from mainline sects.

And the group's inability to come to terms with MCC still rankles some MCC members.

"It seems that their organization is unable to deal with their homophobia," says Rev. Kittredge Cherry, MCC's field director for Ecumenical Witness and Ministry. "It's gridlocked in terms of MCC status."

NCC denies charges of homophobia, and indeed many of its staffers and officials are clearly sympathetic to MCC. Rev. Dr. Joan Brown Campbell, NCC's general secretary, went so far as to participate in the protest in June. Says Cherry: "Having a protest against them is kind of a bizarre experience -- they're so schizophrenic, they join in the protest against themselves." NCC also provided electricity for the June protest as well as access to its cafeteria and bathrooms. And it has accommodated other MCC requests: For the November convention, for instance, NCC agreed to send its board members flyers announcing MCC's forum on the religious right that was held in conjunction with the meeting.

NCC is also undergoing, in ecclesiastical jargon, "a process of discernment," which is another in a series of dialogues about the status of MCC. In New Orleans, council members met with MCC representatives and with members of gay and lesbian caucuses from various denominations.

Nonetheless, there is unlikely to be any official movement soon.

"There is no pending application for anything on behalf of MCC," notes Rev. Eileen Linder, associate for ecumenical relations at NCC.

Two years ago, at the time of the NCC debate on MCC status -which Linder calls "protracted and rancorous" -- NCC officials said that while some member churches sided with MCC, including the United Church of Christ, the United Methodist Church, and the Swedenborgian Chruch, several others indicated that they would pull out of the group if MCC's request were granted, particularly orthodox and predominantly black denominations. Elias Farajaje-Jones, a professor of divinity at Howard University, says many black denominations "have a history of being traditionally homophobic. From their point of view, to allow MCC in is apostasy, the end of the world." He adds, however, that "there are plenty of people in those churches who would object to that stand.

Gay issues have, in fact, created divisions within the member denominations as well as between them. An interim report on MCC noted that "these issues run through the churches, not between them, like a seismic fault," says Sarah Vilankulu, NCC's director of interpretative resources. "It wasn't the Greek Orthodox Church against the United Church of Christ. It was something all the member churches were dealing with in one way or another."

Indeed, with many of the denominations in NCC in virtual meltdown over issues of sexual ethics, particular homosexuality, "it is impossible for NCC to come to a decision unless its members can do so individually," says Linder.

Although sexual ethics is the overriding factor, other considerations will also determine whether MCC ever succeeds in joining NCC. For one, by the lengthy standards of Christianity, MCC is still in swaddling clothes. As Linder notes: "MCC began online in 1986. That makes it younger by 100 years than most of our members and by 250 years for many others."

More crucial are doctrinal matters.

"I am interested in how the MCC brings together people from very disparate doctrinal backgrounds and makes them into a cadre of clergy in a single denomination," says Linder. "Is this truly a national church, or is it a cluster of congregations that has no doctrinal similarity but is just huddled together on the issue of homosexuality?"

The answer lies in MCC's short history, which has shaped its doctrinal character. Perry began his career as an ordained Pentecostal minister, married and the father of two sons. Unable to deny his orientation, however, he resigned from the Church of God of Prophecy and ended his marriage by the time he was 24. After a stint in the Amry, he returned to Los Angeles and gay life, where an unhappy love affair led him to attempt suicide. Finally, Perry became convinced that his mission was to start a new church for the gay community.

Individual MCC churches are still subject to a range of threats and harassment. Vandals shot at King of Peace MCC in St. Petersburg, Fla. in September. Huntsville, Ala., residents protested the opening of an MCC in their town this fall, while the Boise, Ida., MCC floated around for weeks earlier in the year because no one was willing to house it. And in August the government of Argentina denied MCC legal recognition for its Buenos Aires chapter because of "an affinity for public demonstration, including marches and methods of defense promoting not only homosexuals, but homosexuality as a whole."

Thus, while MCC congregations vary in character, they are united by a three-pronged doctrine emphasizing salvation, community, and social action, says Perry. The social action component grows out of the church's experience of persecution, especially in the early days when it faced police raids during services. Inextricably linked with the struggle for gay liberation, Perry and his followers often found themselves in the forefront at demonstrations, butting heads with police. Perry himself conducted numerous fasts and prayer vigils.

"Christian social action means I can't sit around," Perry says. "I don't accept oppression; I live out freedom. I have to get off my butt."

MCC member churches generally have active AIDS ministries, and some have lesbian health and prison ministries as well. The New York City church passes out 1,500 bags of groceries to families every week and has six beds for the homeless.

But in other ways social action may be the hardest part of the doctrine to sell to the congregation, at least in political terms. Last year MCC passed out hundreds of thousands of cards to its members to send to Congress and the president, demanding a repeal of the Pentagon ban on gays in the military. How many were mailed is another matter; members of congress reported that letters opposing the policy were swamped by those supporting it.

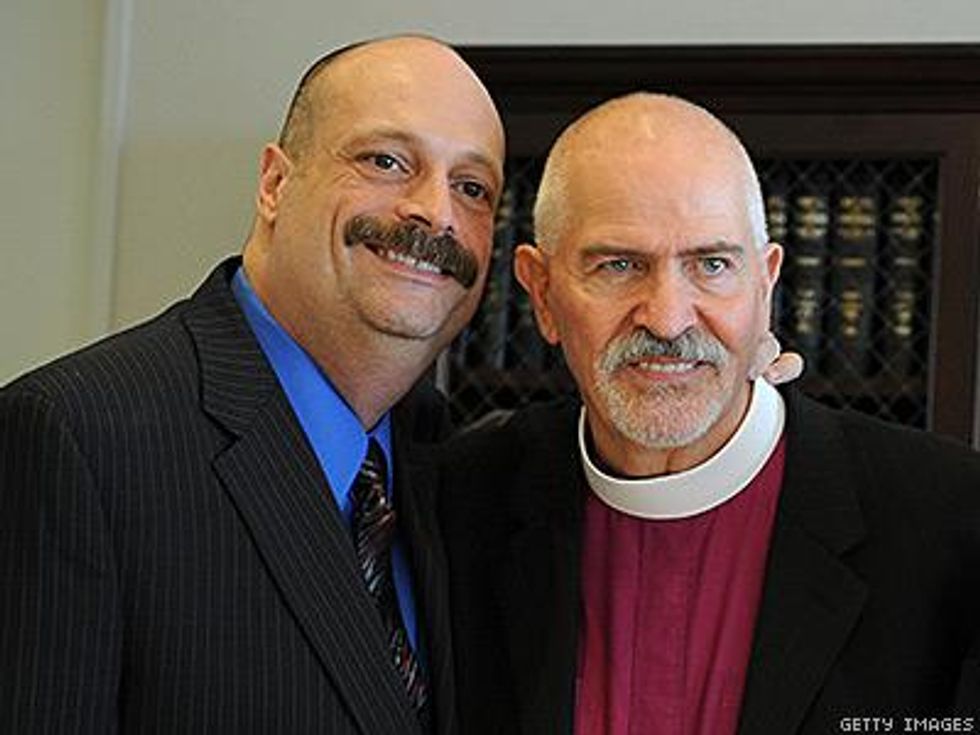

Soon to embark on a stint as MCC's minister of justice, a newly created position, Mel White sees MCC as increasing such efforts.

"MCC represents the new activism," says White, a former ghostwriter for right-wing televangelists Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson. "Those dear guys and women from ACT UP and Queer Nation have risked their lives and are now exhausted. The traditional activist has paid the price to open the door and raise the questions that need to be considered." Now, says White, it is up to MCC members to carry the baton.

Perry's background as a Pentecostal minister is another influence on MCC's overall theological bent, which is clearly evangelical -- providing an ironic link with some of its worst enemies, the evangelical churches.

"Many MCC congregations can't be clearly distinguished from evangelicals," says Schaller. Warner agrees: "A lot of Evangelicals would be aghast at that comparison, but I would make it myself. Evangelicals think evangelicalism means you are heterosexual and have two kids, but it's broader than that. You can go into an MCC congregation and think you're in a typical evangelical church until you see that the couples going to communion are of the same sex."

Newcomers may be put off by the evangelical character of many MCC services. White remembers entering his first MCC church, in North Hollywood, Calif., with his partner after driving around it for several months before finally going in. given their high-liturgical backgrounds, what they found surprised them.

"It was a dumpy little American Legion hall with a cheap cross, plastic flowers, and a whole bunch of blue-collar folks clapping hands and singing," he recalls. "We look back on it now as just plain culture shock."

But for White, as for many other individuals coming out, MCC was a lifeline to the gay community.

"It was literally the beginning of life for me because it was the first time I heard God speaking through a queer," he says. "It won me over."

For gay men and lesbians, he argues, it was "the only game in town. If it was different from what I was used to, so be it. These are my brothers and sisters, and they're on the front line. Where else am I going to go? I have to be there."

Today, MCC churches cover the spectrum, notes White.

"Each congregation reflects the pastor," he says. "Some are warm and enthusiastic and evangelical, and others are far more theological and liturgical and liberal. MCC is not one thing -- it is the sum of many things."

Nonetheless, the church's beginnings are rooted I a conservative theology -- which may be one of its strengths.

"Whereas most of the mainline denominations are organized around religious law, MCC is clearly organized around God's grace," says Schaller. "In today's world, that's a winner. The legalisms of the mainline denominations aren't selling well anymore."

Such an explanation might also explain why MCC's two largest churches are in the Bible Belt. The Cathedral of Hope in Dallas has 1,300 members, while the Sunshine Cathedral in Fort Lauderdale has 750 people show up for its four services each Sunday. The $3.5 million Dallas cathedral, which opened in 1992, is especially grand, with stained glass windows capturing such gay symbols as the lambda and the pink triangle.

"Until you see 1,300 gay and lesbian people worshipping, you have no idea what that does," says Rev. Michael Piazza, the senior pastor at the Cathedral of Hope. "Part of the reason we built such a large building was to create synergy for brining people together in a positive way." The church has also opened a columbarium as well as separate buildings for conducting meetings and counseling.

MCC may have to scramble to keep up with its growth, though.

"One third of our churches are pastored by our laity," says Perry, and that's a particular problem because the churches that thrive are those with full-time pastors. Of MCC's ordained clergy, half are transfers from other denominations; the other half are members who felt called to ministry. The church is also trying to establish ties to the Chicago Theological Institute to train its clergy.

Given the rate of expansion, the usually affable Perry is frustrated that MCC is, in his words, "the best kept secret in the gay and lesbian community." Many of the national gay political organizations "produce, I'm sorry to say, often just a lot of press releases. We live it every day."

MCC's growth is likely to continue as long as other churches fail to address issues of concern to gays and lesbians. The best that most denominations have been able to achieve, says Warner, is a patchwork of compromises, which individual churches can choose not to follow.

And even if the mainline denominations do reach some accommodation with gays and lesbians, says Warner, it may be too little to satisfy them: "What the church really means in about 90% of our society is a social institution based on a heterosexual nuclear family.

"Liberal churches are not going to reconstruct themselves at that most basic level," he continues. "That's why even a church that claims it wants to be open and affirming to gay people may not feel any different from those that are not. It's sort of like a white liberal church that says it welcomes black people, but you don't find a single black person there because the service is so white and middle-class."

"I used to say in the early days that we were working to put ourselves out of business," says Perry. "But that's not going to happen. There are thousands of people in MCC who are very comfortable. They like the way we do business."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes