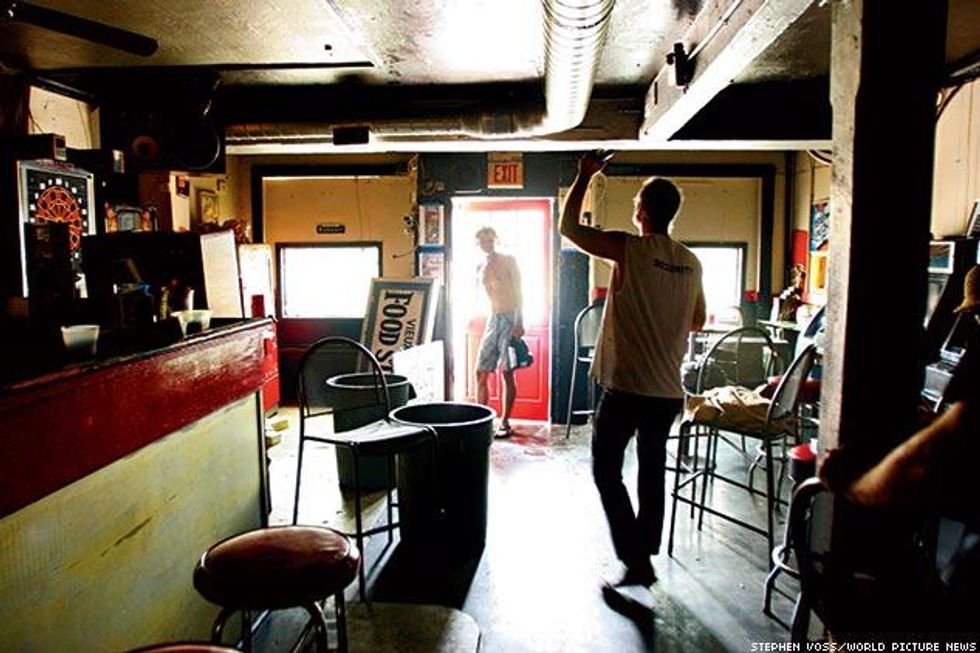

Above: C.W. Stambaugh (in T-shirt) kept his gay bar open before and after Katrina. The Starlight by the Park provided victims with shelter and memories of life before Katrina's devastation.

Above: C.W. Stambaugh (in T-shirt) kept his gay bar open before and after Katrina. The Starlight by the Park provided victims with shelter and memories of life before Katrina's devastation.

Someone forgot to tell C.W. Stambaugh the party was over: The owner of the New Orleans gay bar Starlight by the Park kept his doors open as Hurricane Katrina thrashed the Crescent City. Stambaugh stayed put after the levees broke and the city flooded.

Despite the deplorable conditions, he and a group of about 40 others held their own gay parade, featuring outlandish costumes, on September 4. The party flowed around the corner from the French Quarter bar to Stambaugh's home. "We had Southern Decadence, and it felt good," he says, referring to the city's traditional gay Labor Day bash, founded in 1972, that usually attracts more than 100,000 revelers. "It seemed to lift the spirits of a lot of people," Stambaugh was eventually forced to evacuate, but once the city is again inhabitable he will return. "We will rebuild the city better than it's ever been before," he vows. "We'll be back."

Thousands of other gay men and lesbians say they owe it to the city to return. It's not an easy choice. Many New Orleans residents, especially those in lower income brackets, will likely never come back. During the past weeks some evacuees have found new jobs and new lives in other cities, including Baton Rouge, La.; Houston; and more distant locales. Gay men and lesbians were also displaced to neighboring states -- their lives, careers, education, real estate deals, and health care interrupted. They face the daunting task of rebuilding. But most say they will.

For more than a century this has been their town. Since the early 1800s New Orleans welcomed those with same-sex attractions into a sea of fabulous architecture, boozy decadent affairs, outrageous parades, fabulous costumes, and gender-bending. The city inspired gay poet Walt Whitman to write that Louisiana's "rude, unbending, lusty" live oak trees made him "think of manly love."

Years later a husky man named Miss Big Nelly ran a brothel and boardinghouse for gays, a hotbed of same-sex interracial parties that lasted into the night, according to historians. Then the famed writers came, including Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote. In the 1940s and 1950s the city even had a transvestite bar called My-O-My near the lakefront.

"I will be seeking a way to help the city come back," says novelist Martin Pousson, 39. Before the deluge he had been setting up his new office as writer in residence at Loyola University New Orleans. He knows he is one of the lucky ones: Not only was he able to escape the city for the comfort of his parents' home in Lafayette, La., but Columbia University offered him a position while Loyola is closed. Pousson, a graduate of Loyola, turned down the Ivy League offer. "I want to take part in New Orleans's resurgence," he says. "Ultimately the city will open its doors, and it will need all the hands and minds it can get."

Pousson says New Orleans may seem vulnerable and weak at the moment, but he compares it to a phoenix rising from the ashes -- again and again: "It's a 300-year-old city. It's been burned to the ground and has survived numerous plagues, floods, and hurricanes. It's a crazy quilt of architecture built up over centuries with different styles at different moments. This will be yet another troubled, complicated, but ultimately beautiful layer of the city."

Above: In Baton Rouge, Douglas Froeba (far left) and Tim Youngfill packages to be sent to hurricane evacuees. Some 400 personal supply kits were distributed to HIV clinics and case management agencies.

Above: In Baton Rouge, Douglas Froeba (far left) and Tim Youngfill packages to be sent to hurricane evacuees. Some 400 personal supply kits were distributed to HIV clinics and case management agencies. Ron Marlow, a member of the New Orleans Gay Men's Chorus, is already planning the group's Christmas show. This year it will be held in Baton Rouge, but the chorus will return to its roots. "The gay community has flourished because it is a close gay community," says Marlow, who has lived in New Orleans for eight years with his partner, Michael Knight. "The younger gay men take care of the older gay men. You can carry drinks from bar to bar. The gay community is one of the friendliest gay communities I've ever lived in."

Marlow and Knight were able to escape the city unscathed. They headed to Houston, where Knight's company secured them corporate housing. The couple believe their third-floor condominium in the warehouse district is intact. "Every gay person I've talked to will go home," says Marlow, 44. "Everyone is ready to go back. It's an incredible level of friendship, walking around a community where everyone knows you and has been your friend for a long time. It will be just as good as it was."

Jean Burke and her girlfriend, university professor J.E. Cowden, are also trying to look ahead after absorbing the shock of Katrina. "It's been absolutely awful in some ways -- the idea that this has happened to the city I grew up in -- but we feel very blessed in other ways," says Burke. Cowden's house is for sale, and escrow was supposed to have closed on September 20. She had planned to move into a townhome in a part of the city severely damaged by the hurricane. Burke's house also sustained damage. A hospital social worker, she is on paid administrative leave from her job until September 30 and is waiting to take her next step. "There's a part of me that says, I'm taking early retirement and moving somewhere else," Burke admits. "But it's an accepting city where my friends and my support system are."

Above: Jean Burke (left) and partner J.E. Cowden sit with their dog, Chelsea. All three fled the city of New Orleans prior to the storm and are staying with a friend in Baton Rouge.

Above: Jean Burke (left) and partner J.E. Cowden sit with their dog, Chelsea. All three fled the city of New Orleans prior to the storm and are staying with a friend in Baton Rouge.Even before the hurricane, 49-year-old Robyn Brown -- a leader of the predominantly gay Metropolitan Community Church of Greater New Orleans -- was embroiled in controversy that attracted national headlines. The MCC was being kicked out of its new home at a Catholic HIV/AIDS facility because the Catholic archdiocese did not want to give the impression that it supported same-sex marriage, according to news reports. "That was some of what we were going through, and now we have this on top of it," says Brown, living temporarily in Baton Rouge. "It gives you perspective on what is really important. We moved to New Orleans two years ago from St. Louis, and we did so by choice. There are some people saying they will never go back, but we will definitely go back and rebuild."

Jamie Temple was starting a new chapter in his life when Katrina changed everything. He had just sold his popular leather bar near the French Quarter after 23 years in business and was in the process of buying a bed-and-breakfast on North Rampart Street. Temple is now staying with a friend in Florida. He is one of the lucky ones who can afford to return to New Orleans, but he is now worried about his former longtime employees. "I don't know how they will get jobs in other cities," he says. "In New Orleans, when you get a job in a gay bar, you can have it for 20 or 25 years." A New Jersey native, Temple says New Orleans has been good to him. He arrived while with the U.S. Coast Guard, and he stayed. "In almost 30 years that I've lived there -- I'm 48 years old -- I've maybe been called 'f****t' once," he says. "The Phoenix was a leather bar, and it was perfectly accepted in our neighborhood." Temple became an active volunteer, leading tours of the French Quarter for the Louisiana State Museum. "It has always had a 'live and let live' feel to it," he says. "We had three opera houses before the Revolutionary War. It was thriving city in the 1700s, and I believe it will thrive again."

In the week after the tragedy, as evacuees fought to feel the city from their rooftops, the convention center, and the Superdome, LGBT survivors had their own specific concerns. For one, how would those with HIV or AIDS get their medications when all they had left were the shirts on their backs? "I think people need to think about the images they've seen on television, about the rampant poverty that existed in New Orleans and was often unseen behind the facade of a good time," says HIV Alliance for Region Two executive director Tim Young. The Baton Rouge group was providing medicine and housing to LGBT survivors. "The HIV problem is very similar," Young says. "It exists to a large degree in our community. We know it's a critical problem, and just as we have looked at the potential for levee breaches, this storm has brought the HIV/AIDS population to our community in a similar way. The flood has come in, and we are ill equipped to deal with it."

More than 15,000 people were known to be living with HIV or AIDS in Louisiana at the end of 2003, the most recent year for which CDC statistics are available. An estimated 3,500 of those live in and around Baton Rouge, and a still greater number live in New Orleans. "When you combine the two cities, you probably have the largest HIV/AIDS population in the country, percentage-wise," Young says. And resources were particularly strained in Baton Rouge because the city does not receive Ryan White Act funding. "We're tremendously underequipped. Now we are challenged with attempting to meet those needs for half or more of the AIDS population of New Orleans. They have faced death before, and they faced it again here."

In addition to arranging for medications and counseling, groups rushed to provide HIV/AIDS patients with such personal items as toiletry kits. Walmart gift cards, and food gift certificates. "The gay community is responding quickly. They are on alert and organizing themselves into volunteer networks," Young says.

Above: Despite the devastation, about 40 revelers went ahead and held the annual Decadence Parade in the French Quarter. The Southern Decadence gay fete usually attracts about 100,000 LGBT celebrants.

Above: Despite the devastation, about 40 revelers went ahead and held the annual Decadence Parade in the French Quarter. The Southern Decadence gay fete usually attracts about 100,000 LGBT celebrants.Less than a week after the devastation, the Montrose Counseling Center in Houston was working to get LGBT people -- especially those who felt they might be subject to gay bashing -- out of shelters. After housing was secured for them, case management teams were assigned to evacuees, and support groups were formed. "Initially we are dealing with shock and denials," says spokeswoman Sally Huffer. "Two, three, four months down the line we will still be there for them. Around the holidays is when a lot of stuff is probably going to hit them."

In July, 24-year-old gay man Matthew Cardinale returned to New Orleans after earning a master's degree in sociology from the University of California, Irvine. He had big plans in the Big Easy -- working with homeless youths and starting an alternative newspaper. The problem of teen homelessness was close to his heart: He left home when he was only 14 to escape an "intolerable" situation, and he became a legally emancipated minor at 16. "New Orleans was calling me," he says. "Southern hospitality is a real thing. They know how to treat people warmly." As the storm raged, Cardinale, a Point Foundation scholar, stayed behind in the uptown two-story home of friends to care for his three cats, Beebosh, Annie, and Daphne. But neighborhood fires forced him to leave. He endured a harrowing journey, wading through polluted water to be picked up by the U.S. Coast Guard and then dropped off in the dark in a crime-ridden neighborhood. He waited hours for a bus that never came. "I've become a tough cookie over the years through a lot of crisis situations, but this was really out of my league," he says. He finally made it to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where he's staying with the man who helped him achieve his independence as a teen. But Cardinale won't turn his back on New Orleans. He'll return, ready to help homeless youths and publish his newspaper. "The second they allow people to go back into the city, I'm going to be there," he says. "I want to go back home."

Stay tuned for more stories on New Orleans, including updates on some of the people featured in this story.

Above: C.W. Stambaugh (in T-shirt) kept his gay bar open before and after Katrina. The Starlight by the Park provided victims with shelter and memories of life before Katrina's devastation.

Above: C.W. Stambaugh (in T-shirt) kept his gay bar open before and after Katrina. The Starlight by the Park provided victims with shelter and memories of life before Katrina's devastation. Above: In Baton Rouge, Douglas Froeba (far left) and Tim Youngfill packages to be sent to hurricane evacuees. Some 400 personal supply kits were distributed to HIV clinics and case management agencies.

Above: In Baton Rouge, Douglas Froeba (far left) and Tim Youngfill packages to be sent to hurricane evacuees. Some 400 personal supply kits were distributed to HIV clinics and case management agencies.  Above: Jean Burke (left) and partner J.E. Cowden sit with their dog, Chelsea. All three fled the city of New Orleans prior to the storm and are staying with a friend in Baton Rouge.

Above: Jean Burke (left) and partner J.E. Cowden sit with their dog, Chelsea. All three fled the city of New Orleans prior to the storm and are staying with a friend in Baton Rouge. Above: Despite the devastation, about 40 revelers went ahead and held the annual Decadence Parade in the French Quarter. The Southern Decadence gay fete usually attracts about 100,000 LGBT celebrants.

Above: Despite the devastation, about 40 revelers went ahead and held the annual Decadence Parade in the French Quarter. The Southern Decadence gay fete usually attracts about 100,000 LGBT celebrants.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes