Cover Stories

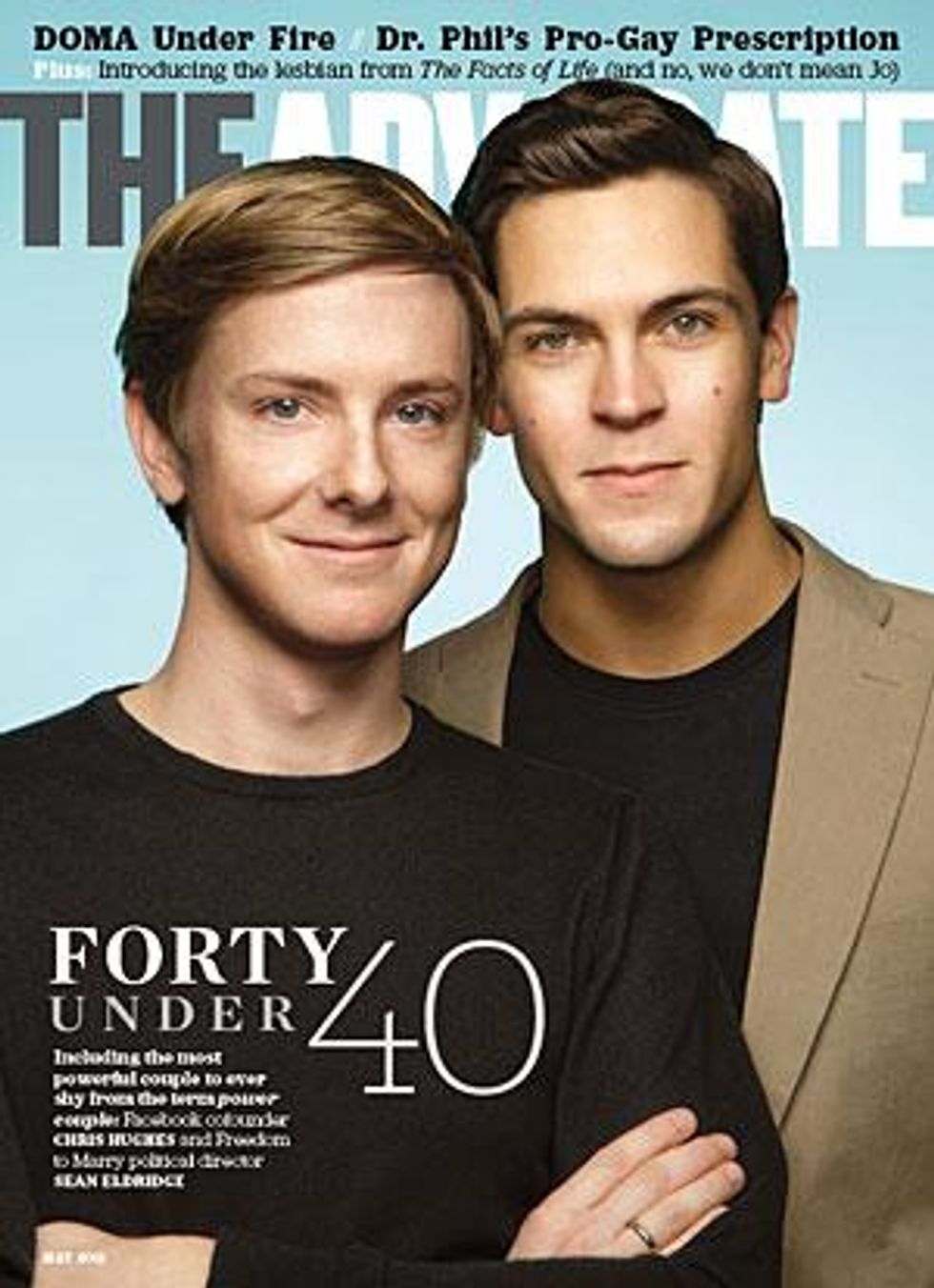

Forty Under 40:Chris Hughes and Sean Eldridge

Forty Under 40:Chris Hughes and Sean Eldridge

April 11 2011 4:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Forty Under 40:Chris Hughes and Sean Eldridge

Forty Under 40:Chris Hughes and Sean Eldridge

The praise isn't just puffery. When sitting down with them -- at their respective offices, and together one evening at their home -- it's clear that these loving partners are worthy role models for a future generation of entrepreneurs and philanthropists as well as gay people who dream of finding their perfect match and being able to legally wed. Individually, they're impressive; together, they're an even greater force. "We both want to have a serious impact on the world," Hughes declares.

The praise isn't just puffery. When sitting down with them -- at their respective offices, and together one evening at their home -- it's clear that these loving partners are worthy role models for a future generation of entrepreneurs and philanthropists as well as gay people who dream of finding their perfect match and being able to legally wed. Individually, they're impressive; together, they're an even greater force. "We both want to have a serious impact on the world," Hughes declares. Hughes had helped create a social networking site that changed the way everyday people interact worldwide, and he'd done his part to elect the leader of the free world. And with more than a 1% stake in Facebook, his net worth tracked at about $700 million, making the couple the wealthiest openly gay men in the world under 30.

Perhaps it's no wonder that Hughes wasn't sure what to do next. "When we started Facebook we were sophomores in college, so I never really went through that, 'Oh, shit, I'm an adult, what am I going to do with my life?' period," he explains. "But I feel like I'm constantly thinking about what impact I can have on the world. I don't think I'm that different than other people in their late 20s [who are] thinking about how to have a fulfilling life." So Hughes embarked on a sort of listening tour, talking to the heads of nonprofit groups, with two goals in mind: to figure out where their money will do the most good and to cook up his next project.

Hughes often heard the same question: Outside of setting up a Facebook page or a Twitter stream, what can we do to make our Web presence more dynamic and interactive? His answer is Jumo.com, a Web platform that intends to be to nonprofits -- everything from the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to Engineers Without Borders -- what Yelp is to restaurants and, frankly, what Facebook is to people. It standardizes the process of interacting with a cause. "We're trying to [make it] really easy for an organization to tell their stories and for people to get to know their work over time."

Like most new-media ventures, Jumo is a work in progress. "What we have out there now is very basic," Hughes explains as he sits in a glass-enclosed conference room, the only private space in the site's open-plan SoHo offices. "Our theory is build fast, release early, and don't wait for it to be perfect." So what you see today is not what the site will be in a few weeks or a few months. While Facebook users "like" things, Jumo users "care," a tag that suits Hughes's worldview about social media. Some commentators gripe that "slacktivism" is rampant online; take, for instance, masses of people changing their Facebook profile pictures to animated characters to fight child abuse. Hughes believes that such trends are more substantive than they seem. "So are they saying that if you tell a friend at lunch, 'Hey, I care about global child abuse right now,' that doesn't matter? These arguments assume that following something is the end, not the beginning." Change, Hughes asserts, begins with discourse. "People talk about what they care about, they share that with their friends, and when those movements are well-organized they can actually have real policy change." It's the legacy of Facebook in a nutshell.

Much as Jumo is a means for a host of nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations to connect to volunteers and donors, Freedom to Marry is a fulcrum for the various state fronts in the battle for marriage--as well as a catalyst for the federal fight. "There are a lot of great projects out there that educate the public," Eldridge says, "but we have to do a better job of connecting these different projects, different events, different marches to the strategy. These one-off moments aren't enough." Likewise, when nothing is happening on the issue in, say, Texas, Freedom to Marry is using social media to help interested Texans raise awareness and money for the coming battle in Maryland.

For the past year Eldridge has helped marriage-activism veteran Evan Wolfson transform the mostly behind-the-scenes organization into a cohesive, public-facing portal. Wolfson has been working on this issue since he argued for marriage equality in Hawaii in the 1990s, but he's been astounded by what Eldridge has brought to the cause. "Sean's youth and youthful sense of empowerment, which is an accomplishment of the gay rights movement, put him in place to believe he should have [marriage equality]," Wolfson says, "to not doubt that for a minute, to have the great confidence that we can make the case and win people over."

Eldridge found inspiration in working on the Obama campaign. "His election wasn't predetermined," Eldridge says. "I think, similarly, our work on marriage, in the gay rights world, on a lot of progressive issues, is not predetermined -- it depends on the work, the message, the people."

Eldridge speaks in eloquent, complete sentences, but when I ask if he intends to go into politics it's the only time in our couple of hours together that he falters a bit. "This is political work," he says. Right, but what about running for political office? "Yeah, uh, we'll see. I think these things are hard to predict."

He bounces back when questioning turns to the president and how he's handling the issue of marriage. "First of all, I think there's a lot of work that our movement still needs to do, including changing more hearts and minds and [pushing for a] DOMA repeal bill. It's not all on him; it's on us as well. I was lucky to be there to watch him sign the bill when he ended military discrimination. That was exciting.... He says he's on this journey, [but] I think he's not moving quickly enough. I know that in his heart of hearts he has respect for us, he has respect for gay people. But he doesn't get a free pass."

Eldridge and Hughes are pretty serious guys. When they're not hosting or going to fund-raisers, they spend most evenings at home reading an array of magazines (The New York Review of Books, The Economist) and books.

They're on the same page about a lot of things: politics ("We support all the same people," Hughes says), sex ("We're monogamous, committed, dare I use the word 'traditional,'" Eldridge says), children ("We'll take our time, but we'll get there," Eldridge says), even exercise (they're both runners). And both of them visibly wince at the term "power couple." But true to his potential as a future politician, Eldridge has a thoughtful response. "I don't think we've ever used that term for ourselves, but I must say having a partner who has similar intensity in his days, a passion for work in the same way, it makes a difference to come home at night and have an intellectual partner. If that's what a 'power couple' is, then great."

"Sean and I are in a really unique position," Hughes says. "We're young and we both want to have a serious impact on the world." They're modeling their giving on the work of Tim Gill and Jon Stryker, who, through their organizations -- the Gill Foundation and Arcus Foundation, respectively -- have fueled progressive causes with their philanthropy. Hughes and Eldridge aren't limiting themselves to marriage equality or gay issues. There's education, cultivating the humanities, international development, and, Hughes says, "creating a more economically just world. There's just so much stuff we care about that I hope we can make change on as many of them as possible. I know it might sound crazy, but we both feel the clock ticking. There's only so much time, and there's so much stuff to do."

But first, though, they have a wedding to plan.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes