Hear them roar. Many of today's queer female bands are grappling with their riot grrrl legacy.

May 23 2012 4:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

When people hear the Shondes for the first time, they're often struck by the Brooklyn-based punk band's driving, Pat Benatar-reminiscent sound, and the violin, expertly wielded by one of the gender-tweaking foursome.

And then there's the name: the Shondes. Shonde rhymes with Rhonda, and it's a Yiddish term meaning disgrace.

That can leave some music fans scratching their heads. "People mispronounce the name and ask us what it means, but that's par for the course," says drummer Temim Fruchter. "We chose a name that's in a language very few people speak."

Their name might require some translation, but their hooks need no such interpretation. All four band members--bassist Louisa Rachel Solomon, violinist and trans man Elijah Oberman, Fruchter, and guitarist Fureigh--are Jewish, each with a different degree of religious observance. (Fruchter grew up Orthodox.) They're all queer to varying degrees too. Fruchter explains, "We're all queer-identified, but we're certainly not a lesbian band," she says. "I don't know what a 'pansexual band' is," she says, citing the label often applied to the Shondes. "But you don't have control over what people perceive about you."

So Fruchter and her band mates take the adoration they've gotten from regional LGBT press across the country for what it is: "Wonderful."

(RELATED: Six LGBT Acts You Need to Know About Now)

"It's a good way for people in all parts of the queer community to connect to us," she explains of the inevitability of being labeled that comes with media coverage. "It's just a fine dance between being pigeonholed and misidentified and getting [celebrated by] niche outlets. Our identities are a part of what we all bring to the table. It's there, but it's not the point."

Fruchter's sentiment seems to capture the feeling of many musicians in the current surge of--excuse the blanket term--lesbian bands. Perhaps a bit more musically diverse than lesbian bands that came before such as, most recently, Tegan and Sara, Gossip, and Sleater-Kinney, they each have a deep ambivalence about being called "lesbian musicians."

And yet they'd all have it no other way.

Alva, who with Phanie Diaz makes up those two thirds (Diaz's sister and third band mate Nina is straight), is happy to be lumped together with other lesbian bands like Gossip. "As long as it's not crappy pop music," she snaps.

If anything, the trio's cross to bear is, as with the Shondes, their name. "It's something that we did a long time ago," she says of the moniker, which references "Girlfriend in a Coma," a 1987 song by the Smiths. "I don't necessarily think we'd ever take it back because we still love the Smiths and Morrissey so much, but I don't know," she trails off, sighing. "Some people think we're a tribute band."

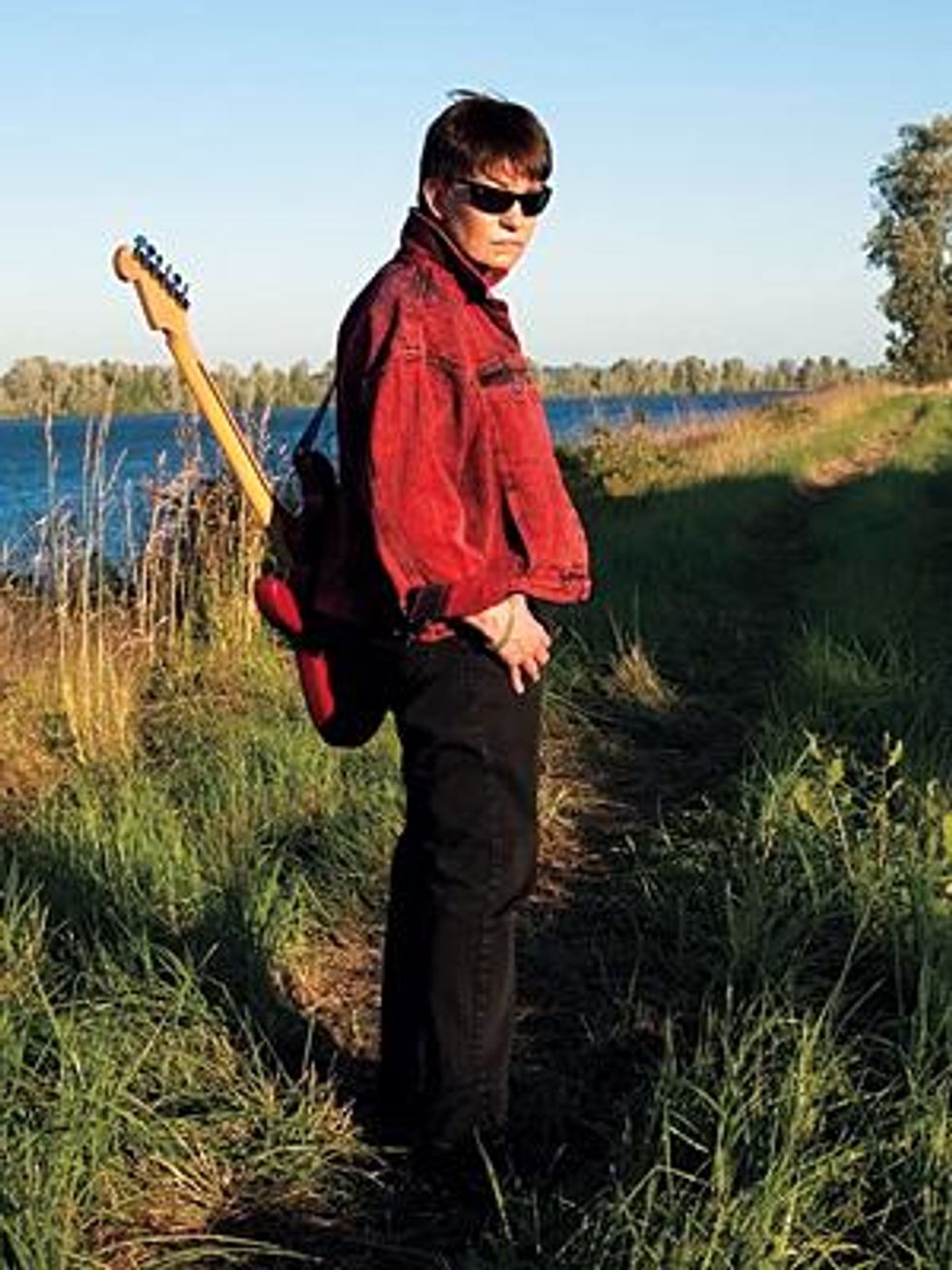

Susan SurfTone might suffer a similar fate, but if so, she doesn't see it as a negative. The surf musician adopted the name to reflect her unusual identity: "I'm a guitar player who doesn't sing."

While growing up in landlocked upstate New York in the 1960s (SurfTone is 57), she was taken with surf music at an early age, thanks to one-hit wonders like the Chantays, whose "Pipeline" hit number 4 on the Billboard charts in 1963, and the Pyramids, who hit it big the following year with "Penetration," considered the last great instrumental surf music hit. "I just gravitated towards that sound," says SurfTone.

A female lead guitarist who makes surf music is rare, but it was rarer still in 1993, when she formed Susan and the SurfTones. She began playing guitar as a child, but as her music evolved from a hobby to a livelihood there were many detours. "I was the first person in my family to go to law school," she notes, and from there she landed a job as an investigator at the FBI. "I never went deep undercover," she says.

Still, she was under a cover of sorts all those years. "I was one of those ones that I think was born gay," she explains. "It was a lifelong struggle."

Not that she had such a hard time accepting herself, but her mother, with whom she was always close, did. "My mother and I struggled with the fact that I was gay," SurfTone recalls. "As long as she was alive I couldn't go fully public with it. Like, if I got any press, you know I would have to fight with her about it. She was not someone that wanted it to be public, because she viewed it as a reflection on her."

SurfTone lived her life openly, but she shied away from public pronouncements. In fact, she had very little public attention until after her mother passed away, in 2009, leaving her daughter with enough money to finance the recording of her album Shore. It also freed her to be publicly, unabashedly lesbian.

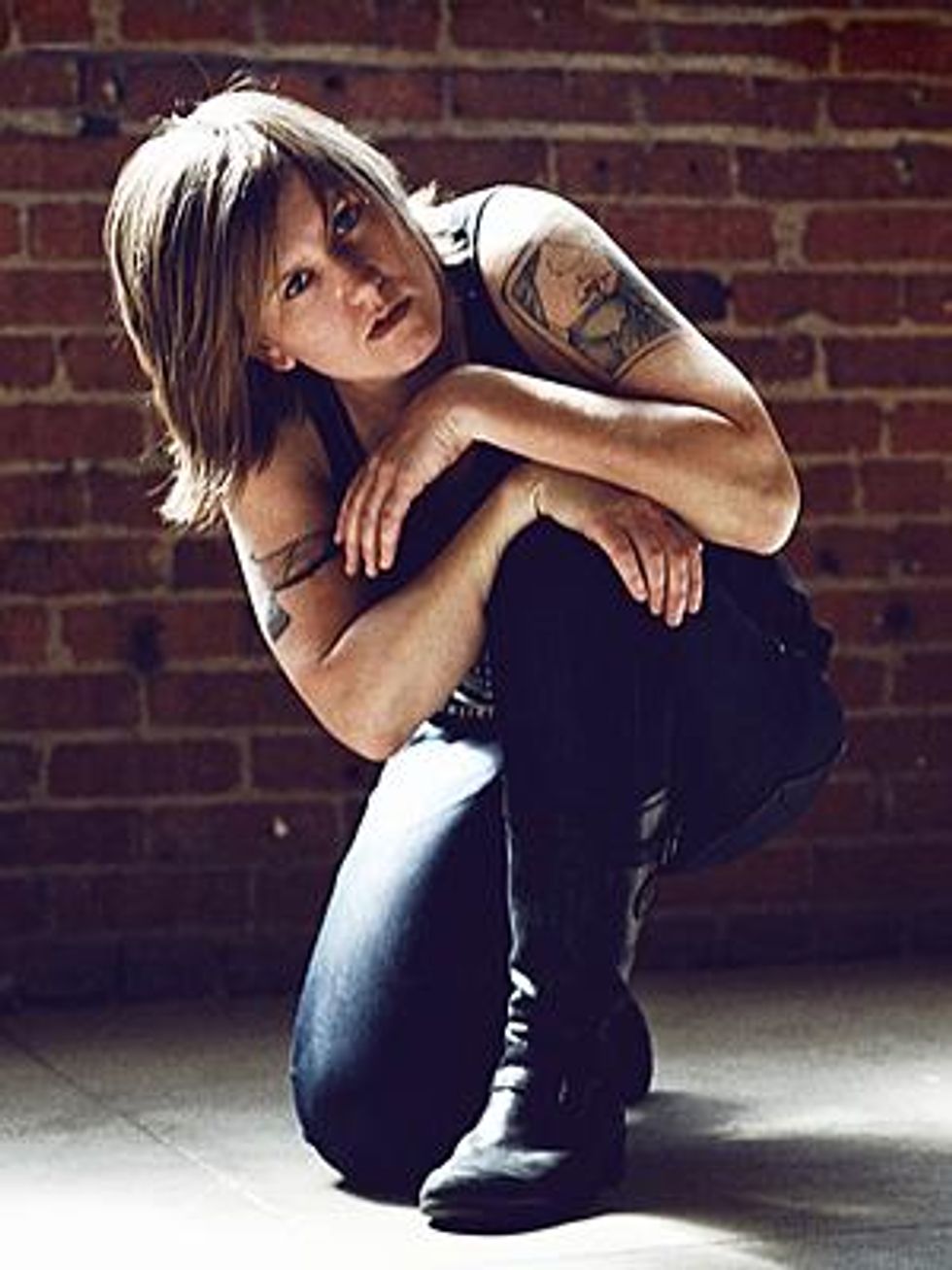

It makes sense, then, that when she had the opportunity to come out on a grand stage a few years later, Starr was wary. "I think when I first got signed I was so worried, I was so terrified to talk about [being gay] because it had only made things worse."

That reticence suited her record label just fine. "When I got to Geffen, they were like, 'We can't have you look like one of the Indigo Girls.' That was a direct quote, by the way." It was the mid 1990s, and Starr had turned drumming in a local band into a major label deal of her own. "I started out kind of being thrust onto the scene and there were a lot of expectations from other people on me. It was like, 'Oh, yeah, this song is going to be a hit. She's going to be a star.' " Her major-label debut, Eighteen Over Me, yielded the hit single "Superhero," which is probably her best-known song to date. "I started out with all of these opportunities, and I have sort of meandered around from then until now trying to find my place in the world."

She never got to do a follow-up album for Geffen. The upheaval of a music industry coming to grips with the digital age meant label mergers and slashed artist rosters. "I was so young," she says. "I got really depressed for a couple of years because I thought it would be easier to run out and get another record deal. I thought it would be easier to run out and get another manager. I just thought because of the fact that my first record was so hyped from Geffen that it would just be easy to run out and make something else great happen."

Starr, now 36 and living in Los Angeles, has formed various bands and recorded several albums. She's toured with such acts as Melissa Etheridge and Mary Chapin Carpenter and her songs have been played on the TV shows The Hills, Life Unexpected, and Pretty Little Liars. She figured out that she has to treat her career like a business, and she has to take responsibility for that business herself: "I am the president and CEO of this company."

Along the way, she came out -- her way. "Inside Out" was a hidden track on her 2004 album Airstreams & Satellites, which Starr considered her best so far, until the most recent one, Amateur, which just came out. The reason the track is hidden, she says, "is because even at that point I was afraid to really put that out there...it's been a really long process for me to come to terms with my sexuality and just being OK with who I am and what God looks like to me and whether or not I go to church."

As DJs, songwriters, and producers, Creep are in a different category than the other musicians here. They're part of the trip-hop, house, and dance tradition, and are musical descendants of Moby and Morcheeba. Though '70s-era lesbian collective Olivia Records broke the barriers for women working behind the scenes in recording, even a scant five years ago sound engineering and other jobs in recording studios didn't offer a female-friendly environment. But as technology has advanced, some of the barriers to entry for women and indie artists have fallen away. What was once cost-prohibitive is now completely accessible with a laptop and Garage Band.

"For the past 10 years, all of us women have literally been producing in our bedroom," says Flax. "We can do this on our own. Record label? What record label?"

The two Laurens met, appropriately enough, on the now-defunct social networking site Friendster. Together they've DJ'ed for the Fischerspooner tour. They aspire to create multimedia theatrical experiences that combine photography, prerecorded sound, and an orchestra and don't fit any definition that has traditionally been thought of as "lesbian band." Nonetheless, they feel a kinship with other queer musicians, such as Trust and Telepathe. And they love the idea of being role models to women of all stripes.

While being queer defines many of these musicians, being women seems to define them even more so.

The Shondes are on Exotic Fever Records, which Fruchter lovingly describes as a "cool, feminist DIY label" that in turn instills an ethic of teamwork in her band mates. "Everyone there works on promotion and business stuff, and we all have great relationships with our fans."

Alva and the Diaz sisters, of Girl in a Coma, are in it for the long haul. "I think we're a good female group," says Alva. "We're all kind of growing right now. I mean, I don't drink anymore, and I take it a lot more seriously."

For her part, Starr has found real contentment in taking direct control of her brand. Her music has deepened, become more emotional. "I was an essential and an integral part of developing the record from the ground up, and I think that was really empowering for me. It felt really, really good," she says.

SurfTone, meanwhile, is reveling in her hard-won public identity as a lesbian musician. "I hope I'm becoming a part of it," she says of the queer music community. "I've wanted to be a part of it for a long time."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered