Timothy Greenfield-Sanders brings us The Out List, an eloquent and moving meditation on LGBT identity. His timing couldn't be better.

June 28 2013 4:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders brings us The Out List, an eloquent and moving meditation on LGBT identity. His timing couldn't be better.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, whose new documentary, The Out List, has just premiered on HBO, likes to say that he has good timing. The photographer and filmmaker arrived in New York a sophisticated and eager 18-year-old from Florida just as Warhol's Superstars were at the height of their fame. That was in 1970. In his second week studying film at Columbia University, he called up a family friend, the underground singer and actress Tally Brown, and said, "I'm here and I have a car," to which Brown, who lived on 181st Street, replied, "Pick me up at 9 o'clock, we're going to some parties." Greenfield-Sanders didn't waste time. Brown, an occasional entertainer at the celebrated Continental Baths and a regular in Warhol's movies, was the young student's entree to a whole universe. "In the first two weeks of being in New York I met Candy, Holly, Joe, Andy," he says -- and if you have to ask, Candy who?, you are either too young or too square.

Brown died in 1989, but Greenfield-Sanders remembers her as "a very, very overweight blues singer who was absolutely brilliant and fabulous, and wore over-the-shoulder kaftans and eyelashes out to here, almost like a drag queen." She looked, in fact, a lot like her friend Divine. You can imagine the impression the parties must have made on a young man new to New York and hungry for experience. "My only regret is that I didn't take pictures," says Greenfield-Sanders. "They were all incredible extroverts, but I didn't have enough sense to shoot them."

He would not make that mistake again. If Greenfield-Sanders got his social education in the nightclubs of New York, he earned his professional stripes as a student at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, where he agreed to photograph visiting speakers for the school's archives. It was a job no one else seemed to want, but it turned into an unexpected education. The glamour days of Hollywood were over by 1974, but many of its brightest stars were still alive. Greenfield-Sanders got to photograph and learn from the best of them. Bette Davis reprimanded him for shooting her from below, then suggested he chauffeur her around town for a week as she tutored him on the work of such legendary photographers as George Hurrell; Hitchcock took issue with the position of his lights only to invite him back to his studio for tips from his own lighting crew.

When he returned to New York with his new wife, Karin, in 1979, the city was emerging from its bankrupt, white flight, "Ford to City: Drop Dead" era, and the couple settled in a converted church rectory in the East Village -- another timely decision -- where Greenfield-Sanders set up his studio. It's a wonderful space, standing aloof from the rest of the neighborhood and varnished by time, like something out of a child's storybook. Lucky visitors -- and I've been one -- are sometimes invited to join him for a casual lunch of bagels and lox from Russ & Daughters, the Lower East Side institution that has been selling smoked fish since 1914. Many of the walls are hung with art by his daughter, Isca Greenfield-Sanders, or by artist friends, whose portraits he's taken over the years. His father-in-law, Joop Sanders, was one of the founders of abstract expressionism, which is how he came to shoot William de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and, well, the list goes on. Greenfield-Sanders reckons he has shot over 5,000 people, which brings to mind Quentin Crisp's hopelessly romantic desire to meet everyone in the world at least once. But ask Greenfield-Sanders which of his many portraits he would take with him to a desert island, and he replies, "a self-portrait." Very diplomatic.

But back to his impeccable timing: New York during the Factory years; Los Angeles for the twilight of the studio gods; then back to New York to shoot artists just as the city's art scene exploded. In the '80s, like so many photographers, he was discovered by fashion -- shooting artists such as de Kooning (again) for Comme des Garcons. It was a sensation, soon imitated by the Gap, but Greenfield-Sanders was too canny to be seduced by the slick, fickle glamour of high fashion, aware that while art photographers can cross over into commercial work, the reverse maneuver is harder.

In 2003, inspired by the movie Boogie Nights, Greenfield-Sanders made another leap with Thinking XXX, a portrait series of 30 porn stars. He hadn't planned on shooting them nude, but when his first subject -- gay porn star Phil Notaro, a.k.a. Kyle Bradford, a.k.a. Chad Slater -- made the suggestion, he realized that was exactly how it had to be: each star dressed and undressed, the photos juxtaposed. Since then, of course, porn has become something of a bore -- we've all seen behind the curtain, we all know how it works -- but when Greenfield-Sanders shot XXX, porn was still intriguing enough for such simple, frank treatment to feel revelatory. A book, co-authored by Gore Vidal, sold tens of thousands of copies. There was a movie for HBO. Talk about the mainstreaming of porn!

For Greenfield-Sanders, XXX also marked the end of his low-key profile, when he was known primarily among a coterie of artists and art fans. At the same time, he recognized that photography was being devalued; the Internet and digital cameras were giving rise to a deluge of images, and it had become increasingly difficult for a picture to stand out from the crowd. The portrait sittings have continued, but in the last decade, Greenfield-Sanders has turned his attention to making documentaries, including The Black List (volumes 1-3), The Latino List, and now The Out List. Each focuses on a minority community in America, in a simple talking-heads style that reflects his approach to photography. And each has materialized at a moment of great serendipity. The Black List -- interviews with black Americans -- premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2008, just as Barack Obama was winning his first primary. Work began on The Latino List as Sonya Sotomayor was being nominated to the Supreme Court. As for The Out List, there could hardly be a more auspicious time for a documentary in which 16 prominent members of the LGBT community make the case for equality.

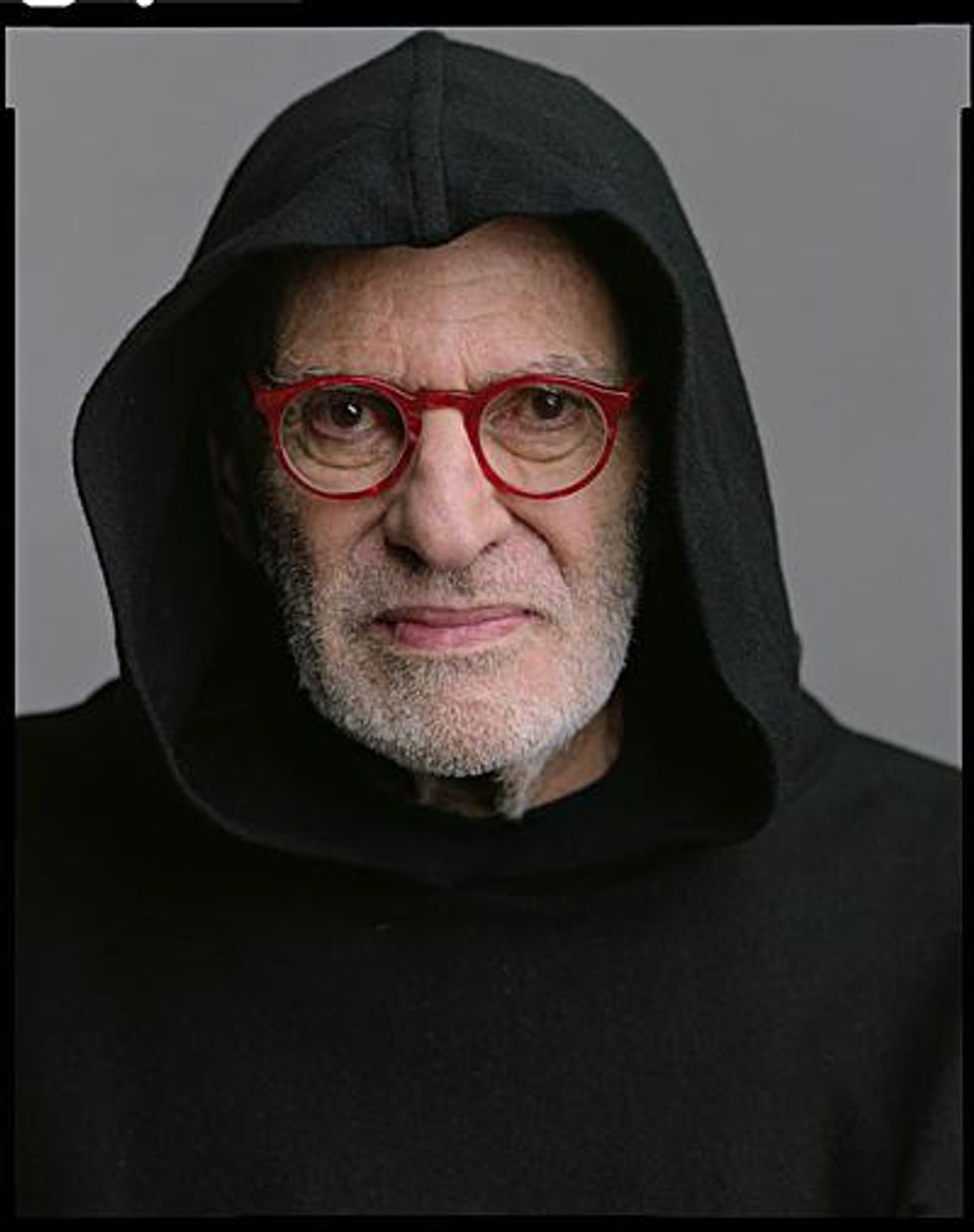

At left: Larry Kramer

At left: Larry KramerIn many ways, the documentary finds Greenfield-Sanders back in the world of Tally Brown, hanging out with the self-proclaimed freaks and outsiders forced by an often hostile society to fall back on their own resourcefulness. There's a wonderful moment when the famously volatile Larry Kramer recalls the life-and-death struggle in the 1980s to shake Americans out of their complacency to AIDS. "You do not get more with honey than with vinegar," he says. "Anger is a wonderful emotion, very creative -- if you know how to do it." For Greenfield-Sanders, who witnessed many friends die of AIDS in the '80s and '90s, Kramer's contribution is the most affecting "because at a certain point, people don't remember AIDS, even, and they don't understand."

Kramer is one of a cacophony of voices that remind us that the LGBT experience is more diffuse and less cohesive than, say, the experience of black Americans. For a start, some of us are black Americans, or -- like Janet Mock -- black transgender Americans. Put Mock alongside Lady Bunny and Suze Orman and Wade Davis and Neil Patrick Harris, as Greenfield-Sanders has, and you begin to see the challenge of talking about a collective LGBT experience. If there is one unifying theme running through the interviews in The Out List, it's that we all have the power to define who we are. That can hardly be truer than it is of Lupe Valdez, a Hispanic lesbian Democrat elected sheriff in the Republican district of Dallas County, Texas, in 2004. She recalls the sage advice of a state legislator not to allow the election to be defined around her sexuality, but to define it instead around her values. That is the tricky high-wire balancing act that all LGBT people are challenged with: embracing our sexuality or gender identity, while refusing to be reduced or boxed in by it.

For Dustin Lance Black, being known as a gay filmmaker and writer is not just a point of pride, but a responsibility. "I'm not going to run from that label," he says in the film. "I am a gay filmmaker. I'm not ashamed of that." At the same time, he wants to get to a point when the distinction is immaterial. "I want to be out of the business of civil rights fighting as soon as possible," he says shortly after recalling the bitter sense of defeat he felt on the morning of November 5, 2008. The same ballot box that had swept Barack Obama into the White House had revoked the rights of gay and lesbian Californians to marry, a result that Black believes cost lives.

But the very fact that The Out List includes people like Harris and Wanda Sykes -- entertainers who have come out of the closet fairly recently -- is a testament to a dramatic shift in the narrative. Change is coming, and faster than many predicted. It's left largely to Christine Quinn, speaker of the New York City Council and a candidate for mayor, to sound a note of triumph. "If you had asked people 10 years ago, 'Would, in 2011, New York State pass marriage equality?' -- if you told them Massachusetts, Connecticut, all these other states had it -- they would tell you you were nuts."

You might ask what qualifies Greenfield-Sanders to take his lens to communities that he is not intrinsically a part of. It takes a certain kind of audacity, after all, to map such emotional terrain, but the cool gaze of the outside observer also helps keep The Out List from being overwrought or didactic. In many ways, Greenfield-Sanders is doing exactly what he's always done with his photography: documenting human lives. Only once, at a screening in Houston of The Black List, has anyone questioned his motivation. "A black guy got up and said, 'How come you, this white guy, are doing this project?'" Greenfield-Sanders didn't beat around the bush or choke on his own justification. "'Cause it was my idea," he replied.

It always comes down to timing in the end.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes