"Donde es la fiesta?" Patricio asked the cabbie at the corner. "Where's the party?" We'd been in Havana for five days, and now it was time to find the gay party. Stationed at the top of La Rampa, people crowded the intersection, stopping traffic. The tropical foliage surrounding the Coppelia ice cream parlor across the street overflowed with voluptuous female bodies wrapped in skirts and animal prints, balancing on platform heels. Shirtless men emerged barefoot from shadows. Others dressed in warm colors open to their waists. They all packed sidewalks in front of the Cine Yara. The restaurant advertised pizza in neon, but its true window displays were the beautiful muscled boys radiant with the day's tan.

"Mariposas!" a driver hurled from his window as he zipped away. And I understood it, not as an epithet for the queers but rather as the best description possible for the scene. It looked like we were in a field of exotic butterflies flittering at that corner in Havana on a Friday night. I tried to imagine what this place used to conjure before the revolution: suits and dresses, flash and smile, money and sex. Now the scene is a faded facsimile of a once-rich tableau, but still vibrant and packed with life.

My partner, Patricio, a college architecture professor, and I last traveled to Cuba (his family's homeland) in 2005 with a group of Spanish students from our temporary home in Barcelona. It was our second trip to the island together, and I remained shy in my beginner's Spanish. It was three days before a massive hurricane would strike the island and thousands would be left without electricity and running water. But not us, the treasured foreign tourists -- we wouldn't lose water or power, nor would we really notice that the island's inhabitants were limping along. But that was not on our minds tonight. Tonight was a party.

Patricio's friend Mariluz had invited us to her home for the birthday party of her gay brother, Eric. We brought fancy bottles of rum, and they mixed it with Coca-Cola. We picked avocados from the backyard tree to make guacamole, and they cranked up a radio that blared American pop music (Madonna, naturally) until they wanted to get out of the house and go dancing. Since gay bars weren't allowed to exist in Cuba at the time, we trekked to the spot near Cine Yara, where the locals knew to ask the taxi drivers for the party that evening. They would transport us to that weekend's secret spot, an ever-moving party to keep the government from finding out.

With the recent easing of travel restrictions, and the hope that the embargo between the United States and Cuba will be lifted completely, this is the same sexy scenario Americans are hungry for -- a chance to visit the island just 90 miles south of Key West, with all its exotic allure. But the common misconception that the country has been stuck in time, with no progress or evolution of thought, remains lodged in our imaginations.

Although gay sexual activity has been legal since 1979, a mere 10 years ago, during my last visit, people could still be jailed in Cuba for public displays of homosexuality. Gay clubs were nonexistent, and people had to meet in clandestine spots for fear of abuse. Now, regular gay pride parades (or congas, in Spanish) take place even in smaller towns and villages.

In 2014, a travel press trip was organized for gay media, organized by the government-owned and -controlled Havana Tours in cooperation with Pride World Travel. Although the itinerary is tightly overseen -- writers weren't allowed to prowl much on their own in search of an authentic experience -- Pride World Travel plans to begin LGBT-focused tours of Cuba this year. It may seem like the latest round of "pinkwashing," since Cuba still ranks high in human rights abuses, but it seems the revolution, which began in the late 1950s and promised equality to all, is finally trying to make amends for its macho maneuvers that persecuted countless men and women for over 50 years.

None of this progress would be possible without the activism of a straight woman with direct ties to the center of Cuban power: Mariela Castro.

Pride parade in Ciego De Avila

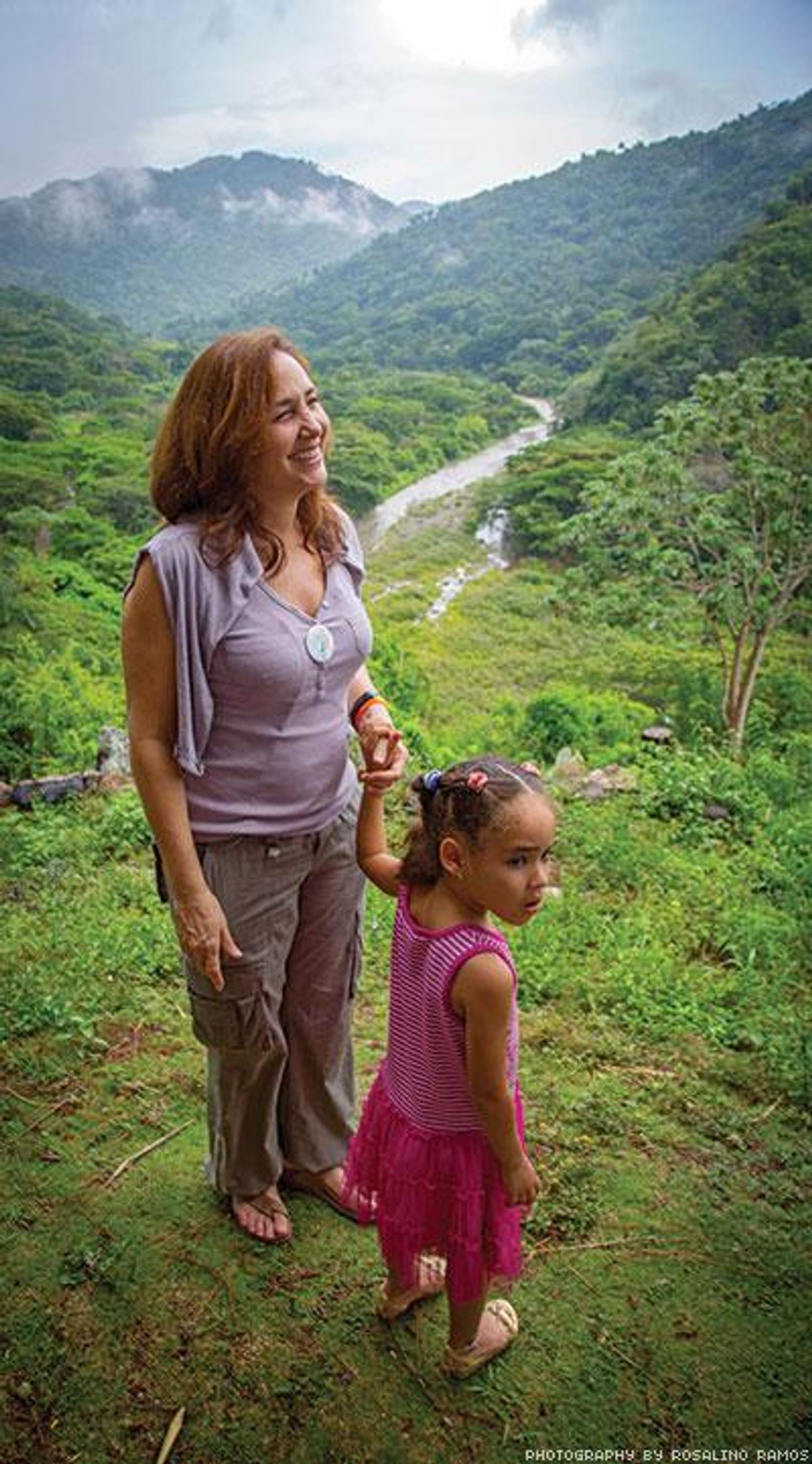

Pride parade in Ciego De AvilaThe director of the Cuban National Center for Sex Education, known as CENESEX, Castro is the daughter of the current Cuban president, Raul Castro, and the niece of the man who led the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro. In 2005, she advocated for allowing

transgender people to have gender reassignment surgery and change their legal gender. Over the past decade she's campaigned against homophobia, with remarkable results. She marches in the front of those Pride parades. She drives to remote mountain towns searching out trans people, lesbians, and gay men who may need her assistance. She's become a queer icon on the island, a single-named saint, the name invoked whenever anyone needs help. "Are you being bullied or abused? Call Mariela."

"I was born into a homophobic society," Mariela Castro told the American filmmaker Jon Alpert in a documentary tentatively titled

Cuba's Sexual Revolution. "I laughed at gays, made fun of them." She explained that one day as a child, a friend said she hurt his feelings, and her ideas about LGBT people began to change. "I was ashamed. From that moment I started to observe, to question, and to investigate. But curing prejudice takes time and work. At every level of society."

Alpert, who has been filming in Cuba for five decades, has made numerous films about the country and traveled there hundreds of times. For this film, which will air on HBO later this year, he captured some of those remarkable LGBT stories: lesbian pig farmers in a remote village, an LGBT baseball game in a tiny mountain town, a trans woman blind in one eye from acid thrown in her face, a new play that features the first same-sex love scenes on stage in 50 years, and a woman in her 70s coming out publicly for the first time.

"I admire the people in this film, their courage and creativity," said Alpert, 66, who is straight. "I like who they are. And every couple of months we call in to check to see if there's been any progress." How ever, he's still unsure what motivates Castro. She remains a savvy political agent, never revealing too much.

"One of the things Mariela did say that was really striking to me," Alpert said, "is that there are many forms of discrimination in Cuba -- against women, against people of color, and she said: 'I'm working on this type of discrimination. When I challenge this and people realize you're wrong, it makes you question all the types of discrimination that you do.' "

At one point, Castro told the camera: "Sometimes my father is ashamed to support me. It hurts, but that's the way it is."

Six of us squeezed into the car. Niko sat up front with a boy on his lap. Eric was the last to get in, and I was sandwiched between him and the others. "Don't talk," he instructed. "Duck down when we see one of them. We don't want to get caught." I did as I was told, trying to hide my face from the police who passed by the car. This taxi was for locals, not tourists. Somehow we'd crossed to the other side. Anxious, I felt someone grope my inner thigh, not Patricio, and I yelped.

"Muy bien, guapo," Eric whispered close to my ear. He then maneuvered a clothes hanger into a small black hole in the car frame and twisted, rolling down the window so their arms could spill out and they could get air. From my crouched position, I noticed duct tape patching a spot in the roof where rust had gnawed through.

Jon and Rosalino filming in Havana with Marta, Reynaldo, and Hector

Jon and Rosalino filming in Havana with Marta, Reynaldo, and Hector

La Gruta nightclub in Havana

La Gruta nightclub in HavanaWe left the lights of La Rampa behind and passed through the fallen buildings of Vedado. No streetlights, just the glow of the headlights bouncing along the pockmarked road. Soon, any semblance of the city was behind us. The car pulled alongside the gravel where other taxis had ferried their passengers from the shambles of the city to the party. Patricio paid for the cab, and the driver told him: "Look for me. Jose. Call my name when ready. Remember. Jose. OK?" Not able to stop myself, I asked in broken Spanish what year the car was. The driver and the rest of our Cuban posse all turned and proclaimed in English: "'56 Chevy." Of course; I should have known.

Draped on trees, strings of white lights illuminated the vacant lot. A swirl of bodies huddled together, populating the backyard (of some farm?) with laughs and wild gesticulations of conversation. Through their heads, I saw another structure across a field with a bare light bulb and a turntable. "A DJ! Way the hell out here," I stage whispered to Patricio, poking him in the rib to see what I saw. "How do they even have electricity?"

We approached the bar, bought a bottle of rum, and paid extra for the plastic cups and chips of ice from a huge block that was slowly melting on the sandy ground. The field slowly became a party. The cabs transported their crews of boys and men dressed in tanks and sleeveless tees across the expanse of roads to their only space of communion.

I thought about how, only too recently, we could all be locked up like the writer Reinaldo Arenas at the Morro Castle, a fort-turned-prison at the mouth of the bay. I had seen the movie

Before Night Falls and thought it would still be like that here: People died to escape Cuba for America. Especially the gay men, who weren't a part of the official party line and were known to be taken to work camps, or to disappear altogether.

"It's never a vacation for me when I visit Cuba," Patricio told me, explaining how his mother and father had fled after the revolution. Every time he came back, I noticed the sadness that seeped into his face. "I could have been born here, stuck here," he'd admitted one time, a rare confession. I nodded as if I understood, but it was something I could only try to empathize with, never having to feel perpetually exiled and guilty. But tonight we smiled ,laughed, and danced with everyone -- designer Italians, black and white Cubans, the few gringo Americans like me, Swiss, Spanish entrepreneurs building all the fancy new hotels. Everyone disregarded the risk for a surreptitious night designed to take advantage of the moment, to forget and enjoy, no questions asked. They left their tiny rooms carved from colonial mansions, their flats shared with grandmothers, mothers, uncles, lovers. They arrived to forget. They arrived to party.

In a snippet of archival footage from 1963, Fidel Castro denounced the young people who strutted around in their "tight pants" for "taking too much liberty," claiming that their "effeminate displays" were destroying society. "A socialist society cannot permit this degenerate behavior." It was this macho attitude that began the persecution of countless LGBT people in Cuba that continued for generations. But that has changed.

Trans pioneer Juani Santos and his brother, Fernando

Trans pioneer Juani Santos and his brother, Fernando

Marta Yonfolk

Marta YonfolkIn 2014, state TV finally aired the annual Gala Against Homophobia that takes place in the heart of Havana at the Karl Marx Theater. Exuberant dancers in feathered and glittery costumes recalled the joyful parties that the revolution had tried to quash.

Flamboyant singing and dancing also takes place openly on beaches around the island. "We would be in jail," one anonymous gay man replied when asked what it was like 10 years ago. "But we have a right to be here."

Mariela Castro now organizes town meetings where people "testify" about stories of homophobia and transphobia. These sorts of events are common to Cubans, since the Communist Party used them for years to reinforce its ideology in the community and ferret out insurrectionists. "It's part college seminar, part pep rally, and part

Jerry Springer," Alpert said, explaining that it's how Castro spreads her message against prejudice, hijacking the political apparatus for her own agenda.

In the film, there is also a panel of six people, including a trans woman who shared her story of hardship living in a small town. When the young woman's mother appeared from the crowd to hug her daughter, Castro facilitated the moment, which feels eerily similar to an evangelical Christian conversion, saying, "Please talk to other mothers to overcome prejudices and to support their children." It's hard not to be moved by such a moment of reconciliation.

It was at one of these meetings that an older man started to explain to Castro how he had been sent to forced labor camps for being gay. Luis Perez demanded that the state give him and others who had been persecuted and abused, some of them tortured and killed, an apology. Alpert's camera followed him into his humble apartment, where he was listening to a Verdi opera on a portable radio. As he ate a plate of rice, he explained how he had been disillusioned and nearly died.

"The revolution had an idea of a new man, and he couldn't be gay," Perez said. He was sent to one of the concentration camps for two years of forced labor. While there he saw a friend nearly blinded after he was punished by being forced to sit in a chair in the middle of the camp and stare at the sun for the entire day. When he confronted Castro about the atrocities committed by her father and uncle in the name of the revolution, she didn't blanch.

"We will remember it, so it will never happen again," she said. "I'm very sorry."

This conflict between the horrors committed in the recent past and a move toward a more inclusive and equitable future remains at the heart of today's Cuba. Travelers to the island may want to visit the Cuba of their imaginations, a place that has been untouched by progress -- with its old Chevys and crumbling colonial mansions preserved in amber. But they must be reminded that such a place is a myth. Even now as Cuba opens up, there are stories that remain untold, and the futures of LGBT people are rapidly being written.

Pride parade in Ciego De Avila

Pride parade in Ciego De Avila Jon and Rosalino filming in Havana with Marta, Reynaldo, and Hector

Jon and Rosalino filming in Havana with Marta, Reynaldo, and Hector La Gruta nightclub in Havana

La Gruta nightclub in Havana Trans pioneer Juani Santos and his brother, Fernando

Trans pioneer Juani Santos and his brother, Fernando Marta Yonfolk

Marta Yonfolk