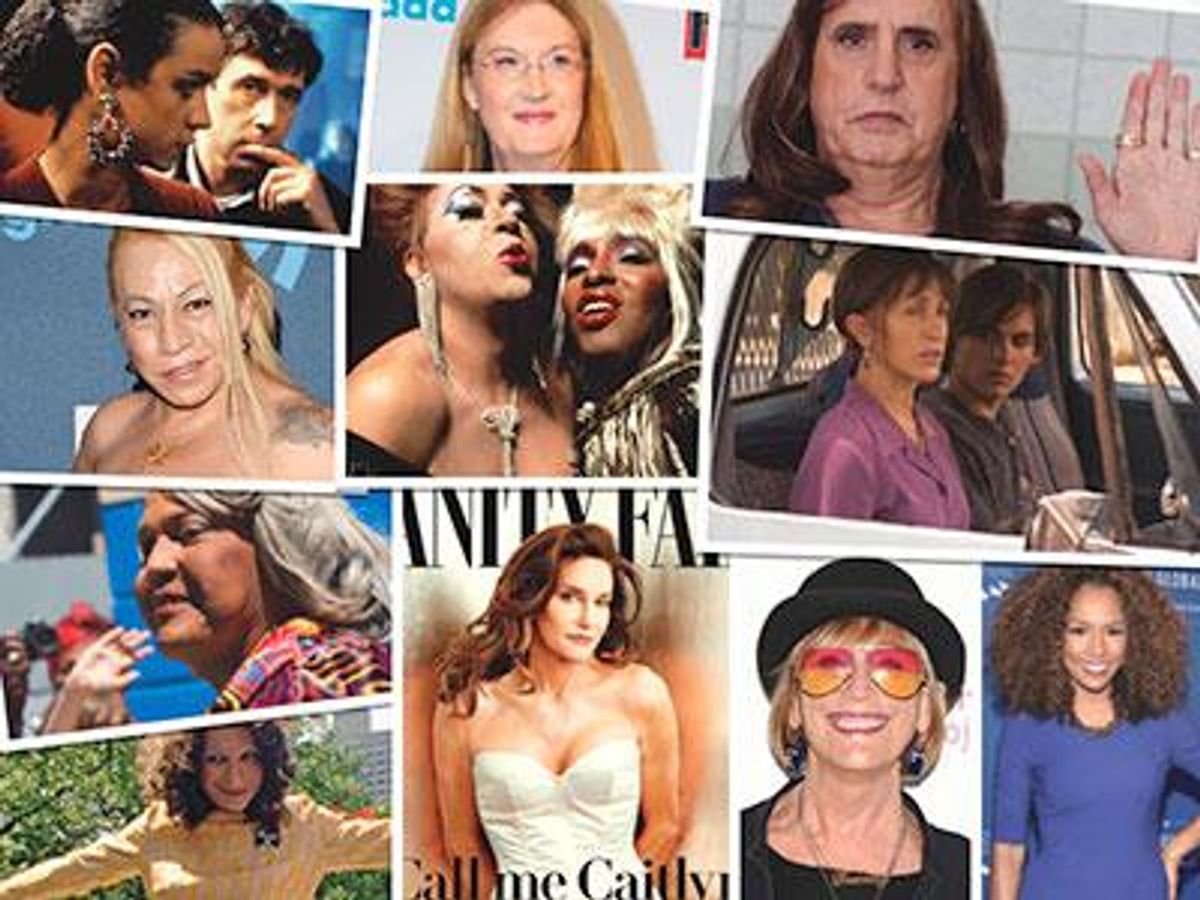

Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of

Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair

, Kate Bornstein, Dorian Corey and Pepper LaBeija in Paris Is Burning

The open secret of trans activists and organizers is that we spend as much time navigating horizontal harassment and internal politics as we do on our proper outward-facing efforts. What is a steady state of affairs for those of us on the inside occasionally rises to public awareness, such as with the "tranny wars," a fight over the use of a word that some claimed with affection and others saw as a vicious slur. Or the "no platforming" of feminists who are critical of trans people. Or the exclusion of trans women from the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival.

Anything done by or for trans people, or any issue that intersects with gender, is inevitably attacked. The battlefields are social media and op-ed sections, and the stakes are control of discourse and who gets to represent trans people.

Internal tensions are not unique to any group of people, but the feeling is more pitched among trans people than elsewhere, a feeling echoed privately by people in all corners of the social justice movement.

The vitriol is just as bad, if not worse, when aimed at fellow trans people. When 12 trans women were featured on the cover of Cndy magazine, other trans women published essays on the cisnormative beauty standards it perpetuated. When Our Lady J became the first trans woman hired as a writer on a high-profile show, Amazon's Transparent, another trans woman wrote that she was the worst possible choice because she's not a "real, everyday trans woman." When I started a website solely for sharing positive experiences, WeHappyTrans.com, one of the first comments I received was "Where is the site for those of us who aren't happy?" And when the first Trans 100 was published, a list of 100 out trans activists, most of the emails I got from trans people were about how terrible I was for not including them.

Those of us working with trans people have come to expect it; we're part of a traumatized and sensitive community. We often say "Hurt people hurt people" as explanation, but it increasingly feels like resignation. Most troubling of all, I know more and more people who are simply giving up, who no longer view trans-centered efforts as worth the inevitable attack. We are ceding space to the most destructive elements of our community just as trans visibility is reaching a crescendo, leaving an uninformed public to either accede to the reality being shouted at them by the loudest trans activists or simply cease engaging in these issues.

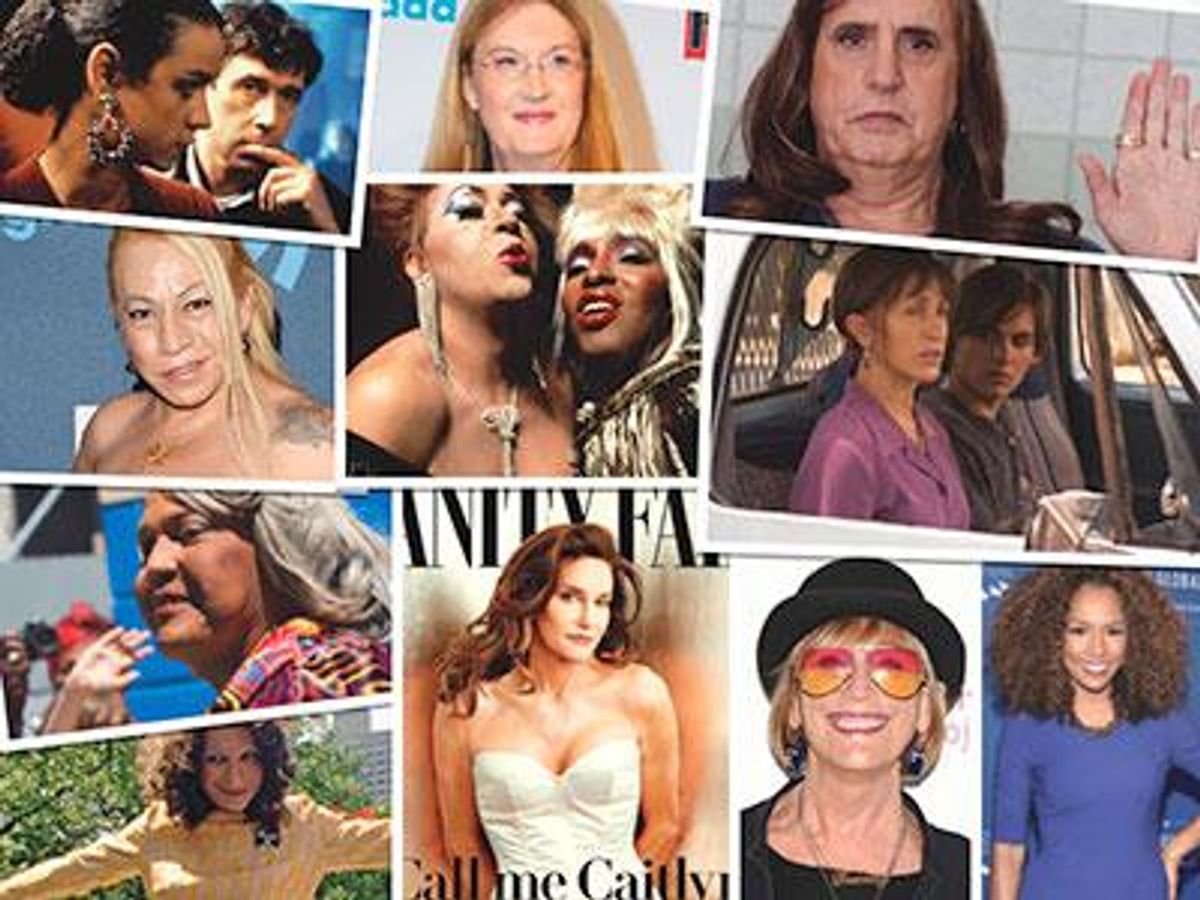

Janet Mock, and Sylvia Rivera

Janet Mock, and Sylvia RiveraIt is possible to look at the sum total of activities aimed at advancing rights, protections, and visibility for trans people and call it a movement. It is a convenient narrative that is at once timely and easy to grasp.

With the battle for gay and lesbian rights on a seemingly inevitable path to victory in the United States, both the media and LGBT organizations have been in search of what's next. And there are plenty of people to point out that no one has been treated less equally than trans people. To this day, hardly a conversation among LGBT organizers and trans people isn't informed, implicitly or explicitly, by the decision to eliminate "gender identity" from the Employment Non-Discrimination Act offered up in 2007 in hopes of giving it a better chance at passing into law without the encumbrance of trans equality (it didn't).

Year after year, anyone digging into the statistics regarding LGBT unemployment, HIV rates, lack of health care, police harassment, negative media portrayals, and violence would see that trans people are disproportionately represented in each and every category.

It was therefore only a matter of time before attention was turned to trans rights. Social media had allowed trans people to find one another like never before, build supportive communities, and become educated on their issues. In 2012, Janet Mock began using #girlslikeus on Twitter, and for the first time trans women were loving and supporting each other in a public space. The groundwork was laid, and the media seized on trans people, simply swapping out sexual orientation with gender identity. The number of trans people may be small, but the stories are nonetheless compelling.

Nearly 17 million people tuned in live to hear one such story, that of Caitlyn Jenner. Not since Christine Jorgensen stepped off an airplane in 1952, if ever, have so many been so interested in someone who does not identify as the gender the world had assumed them to be. The attention could not be attributed solely to celebrity and zeitgeist; Jenner's story was digestible. The public had been primed for it with years of talk shows, news specials, articles, movies, and TV shows. By the time it came out, the contours of Jenner's story were as familiar as the scale of attention was unprecedented. Hardly a year has passed when we haven't heard some variation on the themes of "born in the wrong body" and "living a lie." While none of these previous public performances had commanded as much interest, without them Jenner would have been too alien to comprehend. It was the steady, repeated articulation of a certain trans narrative over decades that allowed millions of people to listen to Jenner and feel empathy rather than bewilderment.

Jenny Boylan, Bamby Salcedo, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy

Jenny Boylan, Bamby Salcedo, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy

The media and their consumers have been particularly interested in one type of trans person, and one type of trans person has been best positioned to articulate their own stories and advocate for their own rights: those whom the world once treated as straight white men. It may have been the inner turmoil and shame of being trans that drove Jenner to such incredible Olympic distances and heights, but it was a culture that centers the experiences of straight white men that made her an icon.

While the details of Jenner's story make it extraordinary, it's the commonalities the story shares with other similar trans people that have shaped the dominant narrative to become a de facto standard. In turn, it's this standard that has shaped what the public thinks of the trans movement and its needs. And here lies the crisis of what appears to be a trans movement. Those who benefited from moving through the world as straight white men truly most need empathy and understanding. Our purported tipping point is predicated on the newfound availability of just such sentiments.

Other trans people, however -- those who did not benefit from such privilege -- are not only in need of much more, they are dying from a lack of it.

The trans movement isn't just a convenient narrative, it is a dangerous lie.

There isn't a trans movement, or a trans community, but rather multiple movements and communities, divided not only by race and class but also distinct histories, leaders, resources, and needs. There are of course some goals, challenges, and victories shared by all. And though there are many exceptions, the lived experiences of most trans people fall into broad camps.

The Jenner story, the one the public is most familiar with, is that of the apparent straight white man, often in a masculine career, married with children, who reveals herself as trans at a later age. Trans women like Jenner often have years of private cross-dressing, and they meet one another through local support groups or weekend-long conventions where they can be

en femme together without risking public exposure. Shared concerns include comportment, learning how to dress like women, makeup and hair, vocal training, the difficulty of finding or maintaining relationships with women, and surgeries. The ultimate goals for many of these women are "passing," being able to move in public space as an assumed female, and finding intimacy. Both are particularly difficult for people who begin the transition process late in life. These women are the source of one of the two tropes that writer Julia Serano discusses in her book

Whipping Girl: the pathetic trans woman.

The World According to Garp (John Lithgow),

Transamerica (Felicity Huffman), and

Normal (Tom Wilkinson) are popular portrayals of this type.

Felicity Huffman and Kevin Zegers in

Felicity Huffman and Kevin Zegers in Transamerica

Many trans women have carved out a space for themselves. Writer Jenny Boylan, founder of the National Center for

Transgender Equality Mara Keisling, surgeon Marci Bowers, artist Kate Bornstein, tennis star Renee Richards, computer scientist Lynn Conway, and countless others used the experiences and opportunities they enjoyed prior to transition to advocate for others. Perhaps due to the connective power of social media, or thanks to the visibility of these older women, many white, queer-identified trans women are transitioning at a younger age and becoming politically active online, many in opposition to the very women who preceded them.

While they vary widely in their particular stories and interests, all of these women share in the unique privilege of having occupied the intersection of identities most valued by contemporary Western society.

Another completely different set of experiences is shared by those who did not benefit from occupying such a privileged space. Black, Latina, and Asian Pacific Islander trans women, along with some white artists and performers who came from gay male communities, found one another on city streets, in nightclubs, and at underground balls. The clear lines between what we now distinguish as transsexuals and queens didn't exist. Total exclusion from mainstream society, reliance on sex work and underground economies, and the necessity of sharing limited resources put a greater emphasis on groups than on individuals.

Gender-nonconforming people were at the heart of spontaneous resistance and action against discrimination and police treatment at Cooper Donuts (Los Angeles, 1959), Dewey's (Philadelphia, 1965), Compton's Cafeteria (San Francisco, 1966), and Stonewall (New York City, 1969), but their individual names and stories are largely lost to history. It's only been through the conscious efforts of a small number of researchers, notably Reina Gossett in recent years, that the central role of trans women in the Stonewall Riots has become known. To the extent that Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, and Miss Major are now icons of the movement, it is thanks to other trans women of color who sought out and shared their stories.

These women often transition younger. As a friend told me when we were discussing the differences in age of transitions, "We had nothing to lose." Kicked out of their homes and churches and left unprotected in schools, they often ended up on the streets. Barriers to conventional employment and the burdensome additional expenses of hormones and surgeries drive many to sex work, where stigmatization of male desire for trans bodies fuels insatiable demand. Those same factors also collide in a judicial system that is at best indifferent to their plight, and often hostile. With their HIV rates exceeding those of every other demographic, including gay men, a whole generation of trans women was lost in the AIDS epidemic. The entire situation conspires to give weight to the oft quoted, if unproven, statistic that the average life span of a trans woman of color is 35 years.

Despite these horrifying facts, the most obvious and abundant qualities of these women are humor, resilience, and creativity. I'll never forget laughing uproariously with a group of trans women (none white apart from myself), until we got the news of yet another murder. There was a quick discussion of the facts, and the conversation returned to its bawdy humor. It's not indifference or numbness but a necessary coping skill. Losing a sister to addiction, HIV, or violence isn't an if among these women, but rather who and when.

It'd be hard to find a trend in popular culture that didn't likely have its original source in black trans women. One oft cited example is Madonna, whose fame is very much built on the styles she picked up from New York City's ball scene. The body modifications long done by trans women, often at great risk to their own lives and intended to increase their value as sex workers, have filtered out and become beauty standards for cisgender women celebrities. The gay men who intersect with the world of street and club girls become the stylists, artists, and tastemakers of an elite far removed from the root. The true source of the Kardashian aesthetic, from hair extensions to pumped lips and large butts, is black and Latina trans women's attempts at survival. One woman's armor becomes another's adornment, a dynamic that leaves the latter adored and the former no less vulnerable. Paris Is Burning may be the only true portrait of this community, and even it was made by someone from outside the community who exploited her subjects.

Straight culture's anxiety around sex is what turns these women into the other trope discussed by Serano: the deceptive transsexual.

The Crying Game is the most obvious example.

Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in

Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in The Crying Game

Judging from TV shows and movies, there is a rash of trans women tricking straight men into bed with them. This lie has gone so far that in 49 states, "trans panic" remains a legally admissible defense for murder. The claim, which still gets repeated in news reports today when a trans woman is killed, is that a straight man didn't know the woman with whom he was intimate was trans, and in a panic turned violent. Putting aside the morally repugnant notion that murder is justified under any circumstances, the truth trans women know is that these men seek us out. Transsexuals feature in one of the most popular forms of pornography, and they comprise anywhere from 15% to 25% of the female escorts in U.S. cities. But media's insistence that trans women are essentially men challenges the masculinity of the straight men who desire them, which is then reasserted through violence. Make no mistake: each time a man plays a trans woman on screen, the end result is very real violence against actual trans women.

These two broad groups of transgender women, the once privileged and the non-privileged, each have a historical precedent that is particularly illustrative -- the former, with Virginia Prince's Foundation for Personality Expression (FPE, later Tri-Ess); the latter, with Rivera and Johnson's Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). Trans historian Susan Stryker sums up the differences succinctly in her book Transgender History:

[On FPE] "... explicitly geared toward protecting the privileges of predominantly white, middle-class men who used their money and access to private property to create a space in which they could express a stigmatized aspect of themselves in a way that didn't jeopardize their jobs or social standing."

[On STAR] "Their primary goal was to help kids on the street find food, clothing, and a place to live. They opened STAR House, an overtly politicized version of the 'house' culture that already characterized black and Latino queer kinship networks, where dozens of transgender youth could count on a free and safe place to sleep. Rivera and Johnson, as 'house mothers,' would hustle to pay the rent, while their 'children' would scrounge for food. Their goal was to educate and protect the younger people who were coming into the kind of life they themselves led."

These dynamics persist in only slightly modified form to this day. My own vantage point is relatively unique in my having been in both of these two very different worlds. My experience before transition was that of an invisible default. The world saw me as a straight white man, well educated and able-bodied, deserving of all the privileges available in our society. I know firsthand what it's like to feel safe and valued wherever I go, to know that my opinion mattered and my voice would be heard. I could identify with every hero of literature, history, or film. Everything in school implicitly taught me that it was people like me who made the world great, and that any flaw I could have would only add to my depth, even be turned into great art. But I didn't consciously know any of this until I lost it, as if the air I had always breathed was suddenly siphoned from the room.

Going through transition, in middle age, while living in a city and taking public transportation daily, was a crash course in otherness. I had to suddenly become aware of my surroundings, tuned in to every look and mocking laugh, always on the lookout for the one who might turn violent. As my appearance changed, I learned that my talents and skills mattered less than my attractiveness to men. The world was no longer for me.

If I had stopped there, if I had made community with only other trans people who had experienced things similarly, I could perhaps have stewed in bitterness, resentment, and victimhood. I could have easily seen the world in terms of what it took away from me, and my indignation would have been righteous. Instead, I became friends with trans people of color and sex workers. My engagement in activism brought me into touch with survivors of violence, people living with HIV, addicts and young people turned away from their families and churches, kids bullied right out of school and onto the streets, and the elders working to help them. If my own early direct experiences cracked open the door to a different world, my new social circles blew it off its hinges.

I write this as a result of hundreds of conversations with hundreds of trans people over many years. Conversations with my elders, peers, and youth, people of every race and class, from across the United States and the globe.

Of course there are more than just these two comparatively visible movements of transgender people. Trans men share a rich history, with less extreme but analogous racial and class divisions. There is an emerging movement of people with a growing range of identities, including, but not limited to, genderqueer, nonbinary, bigender, and agender. Trans people who transition as children often have experiences nearly indistinguishable from their cisgender peers, and there are many people who live out their lives in a gender different than the sex they were assigned at birth without identifying as trans or engaging with advocacy efforts. All of these manifestations are equally legitimate and include both exceptions and overlapping aspects, and none are without some shared challenges. But their histories, their leaders, their needs, and their resources bear virtually no material similarity. Can anyone look at these contrasting realities and maintain the illusion that a single trans movement is possible, much less thriving?

This may sound cynical, but it's not intended to impugn the advance of trans rights; rather, it's to ensure them. There is usefulness in having the wider public presented with an accessible narrative, one that merely nudges them a step further rather than challenge them too aggressively. A sympathetic public will be less likely to oppose legislation, school policies, and cultural products that protect and center transgender people. Hearing Jenner tell her story, watching a news special on trans children, sympathizing with Maura Pfefferman (played by Jeffrey Tambor) on Amazon's Transparent -- these help secure a passive acceptance until more challenging demands can actively be made. Those demands, even the minimal ones desperately needed to protect the health and safety of those trans people most at risk, won't be met unless current progressive leaders, journalists, editors, producers, the leaders and staff of LGBT organizations, HR directors, legislators, etc., invest directly in trans people. They need to hire trans people, train, mentor, and support them. They need to contribute to their projects and center their voices. All of which first requires clarity and understanding. Above all else, they need to listen.

Jeffrey Tambor in

Jeffrey Tambor in Transparent

But listen to whom?

Again and again I've encountered the anxiety and frustration of people, cis and trans alike, who wish to make a positive impact but are unable to hear a clear voice among the clamor to heed. Or when they do undertake an effort, it is met with virulent opposition. Without a tuned ear, it's hard to know signal from noise. And right now, it's the loudest and most aggressive voices that get to be heard. While there is still a very real external struggle with people who fundamentally deny the legitimacy of trans rights, there is an equally important conversation to be had with those who want to help but don't know how.

Who are the loudest and most aggressive voices? Unsurprisingly, it's those who have been taught to believe their voices matter. In the case of trans people, that means queer white women. Not all of them, of course, nor them exclusively, but consistently enough to constitute a clear pattern.

Part of the impotence is that few trans leaders wish to be seen as working against other trans people, and part is that the argument so well developed for other situations fails here: Any opposition to the abusive behavior of another trans person is dismissed as some combination of transphobic, homophobic, lesbophobic, classist, ableist, or misogynistic. Trans activists, particularly queer white ones, have picked up the rhetorical tools developed by people of color active in social justice, particularly black women on Twitter, but wield them without the nuance, experience, or skill of their makers.

The norms of trans discourse have created an absurd situation where the actions of a straight white man can be heavily critiqued and objectively attributed to privileges stemming from multiple intersections of identity, but the moment they identify as a woman the exact same behavior is immune from such critique. Moreover, any implication that the behavior is related to maleness is considered transphobic. I've repeatedly seen queer white trans women trot out statistics about anti-trans discrimination and violence to prove that they are victims of hate and systemic oppression without ever mentioning that it is almost exclusively black and Latina trans women represented in those numbers.

The cost of this is paralysis, simmering resentment, alienation of peers, and a lack of unity. Too many people are increasingly distancing themselves from trans issues at exactly the time when they could have the greatest impact. They are doing so out of fear of and frustration with trans people -- not the trans people who would most benefit from the support being lost, but rather those least in need of it. In the simplest terms possible, the bullies are winning, and the cost of others losing is too high to abide.

I've repeatedly observed that the people who had suffered the most were also the most generous, kind, bawdy, and engaged, while those who were the most angry, self-centered, and despondent had often enjoyed the most privilege. Experiencing otherness prior to transition equipped many trans people of color, and poor white former fags and dykes, with resilience, humor, and insight into intersectional dynamics. However, it's just as true that experiencing privilege before transition often granted white trans people access to resources, education, leadership experience, and an informed awareness of what true equality should look like. If there is a hope in the divisions within the trans community, it's that the widely varying experiences have made for an equally diverse range of skills. In the rare times we do all come together, we're capable of true greatness.

There is no simple solution to these issues. Which isn't the point. Truly supporting trans people will require education and patience. It will require an effort to know us and our issues well enough to make informed decisions. I hope it's true that Jenner's story has opened a door to trans issues, but I know that few who walk through it with the aims of helping are really prepared for the chaos they find inside.

There is a crisis facing trans people, and the response will need to be as intersectional, sophisticated, and persistent as the causes. There doesn't need to be a singular trans movement to rise to that challenge.

Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair, Kate Bornstein, Dorian Corey and Pepper LaBeija in Paris Is Burning

Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair, Kate Bornstein, Dorian Corey and Pepper LaBeija in Paris Is Burning Janet Mock, and Sylvia Rivera

Janet Mock, and Sylvia Rivera Jenny Boylan, Bamby Salcedo, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy

Jenny Boylan, Bamby Salcedo, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy Felicity Huffman and Kevin Zegers in Transamerica

Felicity Huffman and Kevin Zegers in Transamerica Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in The Crying Game

Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in The Crying Game Jeffrey Tambor in Transparent

Jeffrey Tambor in Transparent