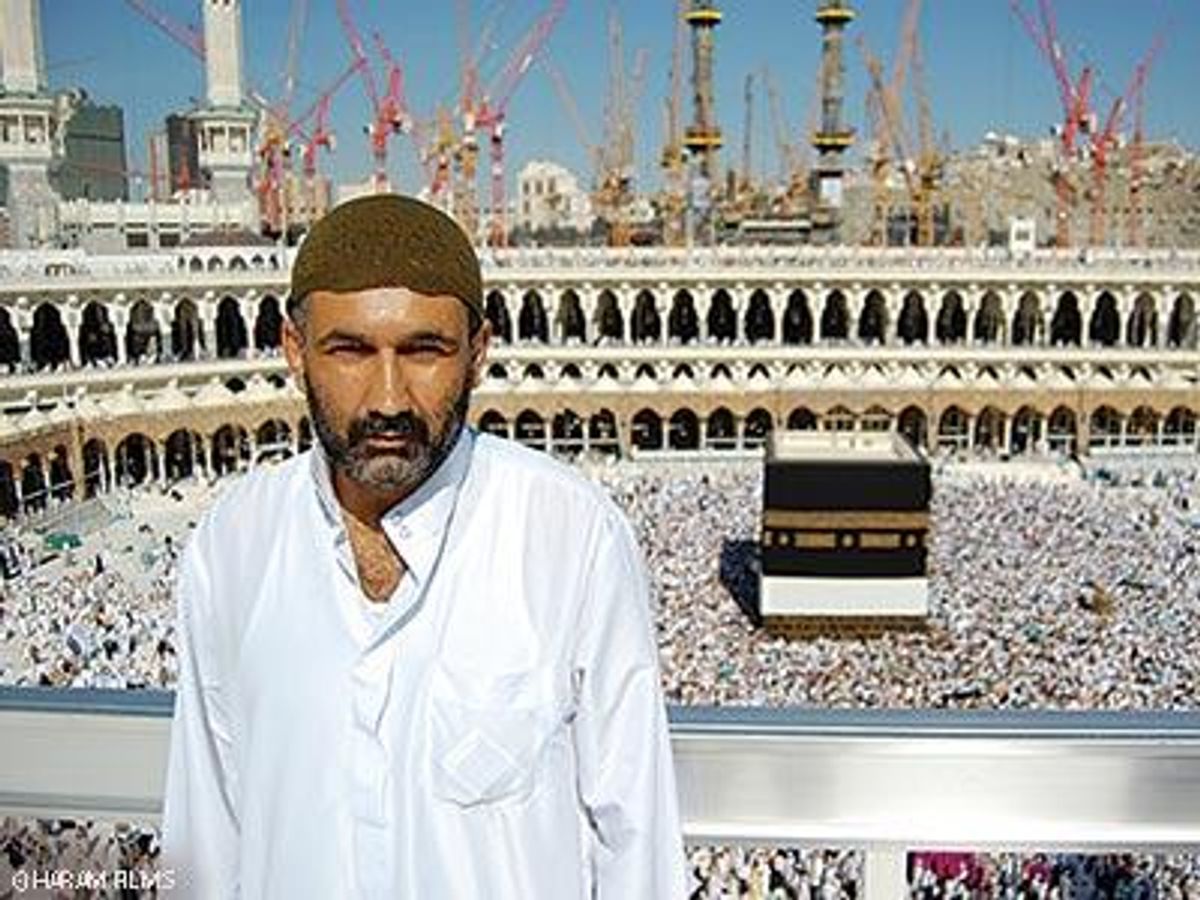

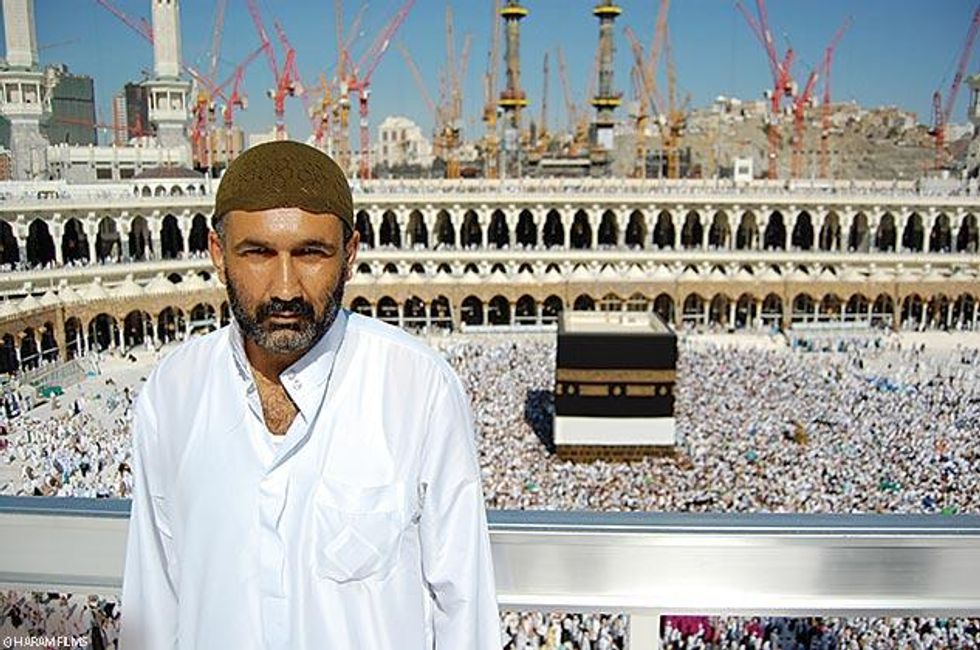

Parvez Sharma overlooking the Kaaba in Mecca

Parvez Sharma overlooking the Kaaba in Mecca

A Sinner in Mecca

In an act of potentially deadly defiance, a gay filmmaker questions and reclaims his faith while exposing Saudi Arabia's violent conservatism.

For many, Mecca is a city in Saudi Arabia shrouded in mystery: impenetrable, unknowable. But for devout Muslims, the hajj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, one of Islam's holiest sites, is a journey one must make in their time on earth.

Photographing or videotaping the hajj is strictly forbidden, so to see the swirling masses at the Kaaba, the sacred cuboid building in the middle of Mecca, as seen in Parvez Sharma's intensely personal documentary, A Sinner in Mecca, gives audiences a voyeuristic thrill. We feel the claustrophobia, the danger, the violence as the camera -- strapped secretly to Sharma's neck -- approaches the sacred object.

Many fundamentalist Muslims already revile Sharma, a proud gay man whose 2007 film, A Jihad for Love, questioned Islam's treatment of LGBT people. Though homosexuality is punishable by death in Saudi Arabia, Sharma decided to go back in the closet -- both as gay and as a filmmaker -- to get the visa and permissions to make the hajj. Like a carefully constructed thriller, the film shows the tension that exists as Sharma makes his way toward the Kaaba; as irrational as it is, we wonder if he will be struck down for his impertinence to defile this hallowed object. He finally touches it, and the world doesn't end. He feels relief, but he's not out of danger yet. Sharma is ultimately traumatized by the experience.

The film is more than his struggle with reconciling his faith with his sexuality: it's an open challenge to Wahhabism, the ultraconservative movement within Sunni Islam practiced by the majority of Muslims in Saudi Arabia. And it's this political examination and challenge that has prompted death threats and hate speech directed at Sharma, and required extra airport-style security at many of the screenings in North America and Britain.

"Conservative Muslims are organizing themselves and coming with only one

purpose in mind: to publicly attack and shame the film," Sharma says. "At a U.K. screening, it was a group of Saudi women who condemned the film in public. I tried to defend it. I have experienced hostility face to face, but this time was different. I crumbled.

They followed me out of the theater. It was an awful experience."

During the Q&A session at the film's first screening at HotDocs in Toronto, a young gay Muslim man was inspired to come out, thanking Sharma for making the film for all other gay Muslims who may never be able to make the hajj -- but that experience was followed by hostile questions. When Sinner screened at Outfest in Los Angeles this summer, where it was awarded the Best Documentary Feature, a group of Iranians arrived to attack Sharma's motivations for making the film.

"They said I was fooling people because I dared to film the experience, and filming and prayer don't go together, so I shouldn't claim any sense of religiosity," he says. "But being a filmmaker and a religious Muslim, I can divide my brain into halves, and it's my natural instincts to film. No way I wasn't going to document the most important journey in my life."

Eager to reach as many viewers as possible, Sharma hands out DVDs to people who ask so they can organize screenings in Muslim world capitals. The film will be released in New York on September 4 and in Los Angeles on September 11, which will make it eligible for awards consideration, and Sharma says Netflix will stream the film. He hopes to reach a wide Muslim audience so that they can help change the religion that "has no resemblance to Islam as it was originally intended."

"People are reacting very strongly. But most are reacting to a film they haven't even seen." --Jerry Portwood

A Gay Girl in Damascus

A Gay Girl in Damascus

While on the cusp of revolution, Syrians searched for Amina, a young lesbian abducted by her govenment. But Amina wasn't real.

When Amina Abdallah Arraf al Omari, a gay Syrian-American blogger and activist, was reportedly abducted by government forces in Syria in 2011, the international community took keen, almost obsessive, notice. Spurred on by the tireless efforts of her Canadian girlfriend, Sandra Bagaria, to secure media coverage, Amina's was the perfect human-interest story. An openly gay Muslim woman in the Middle East whose blog, "A Gay Girl in Damascus," documented the early stages of the revolution in Syria, she became the progressive face of what the Arab Spring was trying to accomplish.

But there was a problem: Amina didn't exist. Her online persona was, in fact, created by a middle-aged, straight white American man from Georgia.

In the documentary A Gay Girl in Damascus: The Amina Profile, filmmaker Sophie Deraspe teams up with Bagaria to unravel the twisted series of events in this strange saga. "This is a film, and we're at about the 20-minute mark," Deraspe recalls telling Bagaria in 2011. "More has to come." At the time of the conversation, however, Bagaria was far from ready to get involved. She had just been the subject of one of the most widely reported cases of "catfishing," and the public reveal of Amina's true identity had left her deeply humiliated. Her early pleas for help found answers in the State Department, NPR, The Guardian, Amnesty International, and a number of individual activists, many of whom diverted their attention from the real atrocities being committed in the country. Duped herself, Bagaria had unwittingly dragged many along with her.

The film, now available via the Sundance Now Doc Club (DocClub.com), serves as a warning in this Internet age, but it is also a powerful tribute to the people fighting for liberty in Syria. "I knew it was going to be a lot about the contemporary world," Deraspe says, "about sexual identity, the media, how we connect with each other romantically and across cultures, but I didn't expect to learn the impact it had on Syrian people. I didn't know that actual Syrian people had been looking for Amina, that they had exposed themselves, revealed themselves to the authorities by actively trying to help a woman they thought was in danger. The Amina affair, it hurt a lot of people." --James McDonald

Khader Abu-Seif and Naeem Jiryes in Oriented

Khader Abu-Seif and Naeem Jiryes in Oriented

Oriented

Caught between worlds, gay Palestinians search for a fulfilling sense of identity.

For 15 months, filmmaker Jake Witzenfeld, a straight British Jew, followed three gay Palestinians -- Khader Abu-Seif, Fadi Daeem, and Naeem Jiryes -- as they lived their lives in Tel Aviv. Israel's 1.7 million Arab citizens account for 20% of the country's population, but as members of this large minority, Abu-Seif, Daeem, and Jiryes are caught between worlds, straddling rigid divides. They feel themselves to be less Palestinian than those in the Occupied Territories, and though they hold Israeli passports, their ethnic identity resists the label "Israeli." They live in Tel Aviv, a haven for gay life in the Middle East, but that link to their fellow LGBT Israelis is tenuous.

Witzenfeld initially sought to explore the confused space occupied by gay Arab-Israelis, to learn how young, progressive Palestinians orient themselves within their society. For them, even the simplest decisions -- whether to go out to an Arab or Jewish club, whether a guy is too Zionist to date, whether to pre-drink to Hebrew or Arabic music -- carry undue weight.

But then, war. Captured on film, the devastating Gaza conflict of the summer of 2014 laid bare the precarious position of Palestinians generally in Israel. "At night, lots of right-wing radicals would run past our apartment screaming, 'Death to the Arabs!' And you understand why people [Israeli Jews] are so irritated," Abu-Seif says. "They don't want to live their lives afraid" of rockets from Gaza, of kidnappings, he explains. "But from the other side, they aren't aware that they are terrorizing me, that they terrorize Arabs living inside Israel." The war also proved to Abu-Seif that his sexual and national identities are ultimately inseparable. "To define myself just on my sexuality would be great, but I cannot. Every time there is a war, every time something happens politically, automatically, all I am is an Arab. The enemy."

Oriented (go to OrientedFilm.com for screening schedule) doesn't offer answers. It aims to unsettle and confuse, to shake off preconceived beliefs and inspire conversation. "I want Oriented to be the kick in the knees that gets people talking," Witzenfeld says, "because we need it." --J.M.

Parvez Sharma overlooking the Kaaba in Mecca

Parvez Sharma overlooking the Kaaba in Mecca A Gay Girl in Damascus

A Gay Girl in Damascus Khader Abu-Seif and Naeem Jiryes in Oriented

Khader Abu-Seif and Naeem Jiryes in Oriented