Blockbuster director Roland Emmerich brings the landmark riots to the big screen.

August 31 2015 4:00 AM EST

May 26 2023 2:57 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Blockbuster director Roland Emmerich brings the landmark riots to the big screen.

As I enter the set of the film Stonewall, a sense of surrealism immediately sets in. The cast and crew are standing on a Montreal soundstage in an industrial warehouse on a hot, muggy night in July of last year. They're here to recreate a crucial bit of gay history. I have to look up as a reminder that what I am seeing is not real. The surrounding set is a meticulously reconstructed Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, circa 1969. The offices of the original alt-weekly newspaper the Village Voice are here, as are a number of local businesses. At the center of it all is the Stonewall Inn, the drinking hole now widely regarded as ground zero for the contemporary LGBT civil rights movement.

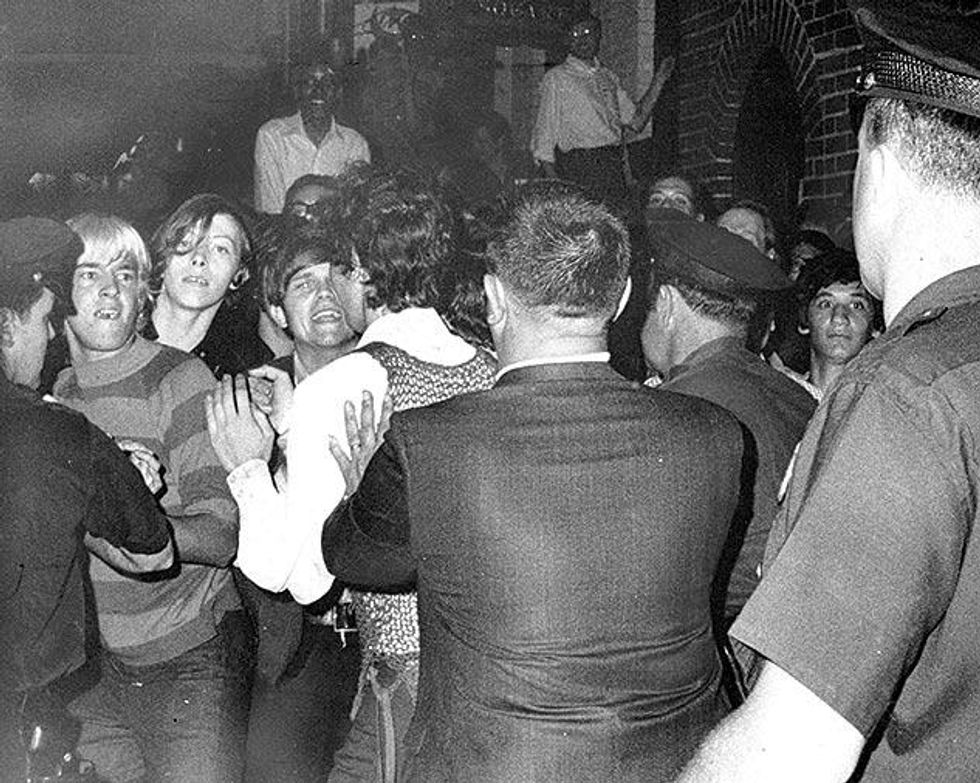

And this, as it turns out, is an especially fortuitous night to be on set. The actors are replicating the wee hours of June 28, 1969, when some LGBT patrons of the Stonewall Inn lost their patience with ongoing police harassment. Some have suggested that the death of Judy Garland, whose funeral had been held that very day in 1969, played a part in that night's events. Whatever it was, something snapped, quite collectively, and after an especially nasty interrogation by police, patrons of the Stonewall Inn began to pick up anything they could -- bricks, stones, coins -- and hurl it at the police outside the bar. That spark led to five nights of rioting that marked a shift in American civil rights -- an event seen as so significant that President Obama cited it in his re-election speech.

Above: From left: Vladimir Alexis (with head scarf), Jonny Beauchamp, Jeremy Irvine, and the cast of Stonewall. (Phillipe Bosse)

Above: From left: Vladimir Alexis (with head scarf), Jonny Beauchamp, Jeremy Irvine, and the cast of Stonewall. (Phillipe Bosse)Fog machines are putting a mist in the air, helping to recreate that hot, muggy night. And the pyrotechnics crew is lighting a few fires; the rioters are being depicted forcing police into the Stonewall Inn and then setting it alight. It's striking how real everything feels. I could almost be there on that fraught night, when tempers flared so badly, so epically, that they ushered in a new era.

Lording over this elaborate recreation is director Roland Emmerich, the gay German filmmaker best known for blockbusters Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow and 2012. "This is very personal for me," says Emmerich, in between takes. "I wanted to do it now, as I'm very active in the marriage equality movement. I thought now is the time to do this." Though Emmerich couldn't have known it then, the timing does turn out to be remarkable: One year after Stonewall was shot, the U.S. Supreme Court would rule that same-sex marriage is a constitutional right.

For Emmerich fans, the move to make a relatively low-budget ($20 million) film like Stonewall might seem a surprise. Famous for bombastic CGI-soaked disaster films, Emmerich has been called the "Master of Disaster," a title once held by '70s icon Irwin Allen, director of The Poseidon Adventure. "I like the idea of going from a bigger film to one that's more personal, like this one," Emmerich says. "I liked the beauty of these characters. I know people know me as making huge films with big budgets. I like the idea of alternating between a film like that and a film like this one."

While the story of Stonewall has become legend, Emmerich and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz (Brothers and Sisters, The Slap) decided the landmark moment should be told through the very personal lens of one character as he journeys to New York from the American countryside in search of his gay identity. British actor Jeremy Irvine (War Horse) plays Danny, a young man desperately searching for love in the bars and streets of Manhattan. Though Emmerich was eager to illuminate this step toward liberation, he also wanted to remind people of just how different things were for queer people in 1969: Sodomy was still a criminal offense in many states; and even in cosmopolitan, worldly New York, wearing drag could land you in the slammer. If being bashed was the problem, you couldn't go to the police, who were often every bit as homophobic as the bashers.

Above left: Otoja Abit as Marsha P. Johnson in Stonewall. Above right: Marsha P. Johnson and Kady Vandeurs at a New York City demonstration in support of the gay rights bill "Intro 475" in 1973. One of New York City's best known drag queens, Johnson fought in the Stonewall riots and went on to co-found the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Sylvia Rivera.

Above left: Otoja Abit as Marsha P. Johnson in Stonewall. Above right: Marsha P. Johnson and Kady Vandeurs at a New York City demonstration in support of the gay rights bill "Intro 475" in 1973. One of New York City's best known drag queens, Johnson fought in the Stonewall riots and went on to co-found the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Sylvia Rivera.Danny is a lost young man, longing to find other people like himself. His character is fictional, but Emmerich felt having a fictional character guide the audience through true historical events was the best way to proceed. Emmerich is especially proud of the cast, which also includes Jonathan Rhys Meyers (who plays Danny's older love interest), Ron Perlman (as Ed Murphy, based on the actual crooked manager of the Stonewall Inn), and Jonny Beauchamp (as Ray Castro, as a streetwise and effeminate young man, who was also an actual participant in the riots).

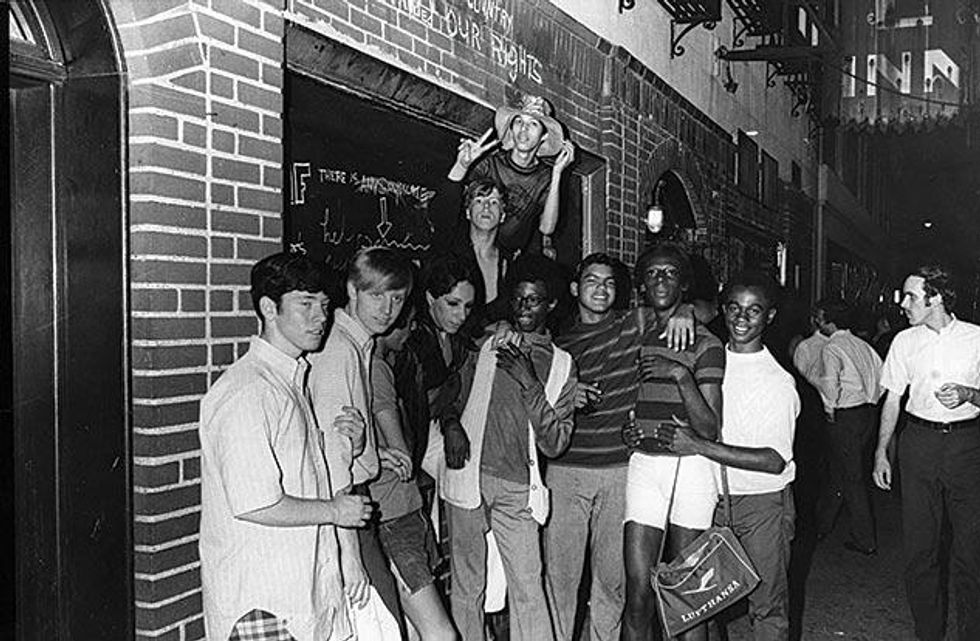

"When I look back at what these kids did," Emmerich says of the young rioters at Stonewall, "I'm in awe of them. They had nothing to lose. Now being gay is not such an issue, of course. And that's progress. There were so many people who were just bystanders. There is this famous quote from a Black Panther who went down and saw what was happening, and he said, 'The fem boys were the ones who were fighting the hardest.' That quote stuck in my mind. Because traditionally, we as a gay people tend to look down on the fem guys. I wanted to make them -- the fem guys, the loudest guys -- the heroes."

Emmerich's awakenings as a filmmaker happened much earlier than his self-identification as gay and his political awakenings. He still recalls the first film he ever saw in a cinema, David Lean's 1965 historical epic Doctor Zhivago. "My older brother took me to 2001: A Space Odyssey, and I'll never forget that. When I went to America when I was 13, I went to a drive-in and saw Planet of the Apes. I saw it several more times. People were like, 'How many times can you see this film?' I also liked The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno. In fact, The Towering Inferno was a bit of a model for Independence Day."

By his own admission, he came out rather late. "When I was a young director in Germany, I didn't want the word 'gay' in front of my name, because the gay directors in Germany made such different films than the ones I was making. I thought I'd leave that to them. But when I came to Hollywood I realized a lot of the big directors were gay -- that anyone could be gay and direct anything."

Emmerich befriended a number of famous directors, including Joel Schumacher and Bryan Singer. "I realized you didn't have to be limited in any form to do what you want to do. Look at Joel, he made Batman movies. And Bryan made a Superman movie."

That realization came after Emmerich had come out to his friends and family. "I came out in phases. First I told my friends. I was an American, in my 30s," says the filmmaker, who still effects a boyish charm at age 59.

Abpve: Jonny Beauchamp as Ray Castro and cast on the Stonewall set. (Phillipe Bosse)

Abpve: Jonny Beauchamp as Ray Castro and cast on the Stonewall set. (Phillipe Bosse)The first gay-themed film that had an impact on Emmerich is telling: The Boys in the Band, William Friedkin's adaptation of the Mart Crowley play (released in 1970, just one year after the Stonewall riots). "I first saw it in Germany. I wasn't really even aware people made films like that." The Boys in the Band set the standard for the debate over negative-versus-positive images of gay characters on the big screen. (The film's release predated the common use of the word "queer" in academic and activist circles.) And this debate is something Emmerich was keenly aware of as he was deciding on a tone for Stonewall: How to make a film about this moment of liberation, one he wanted to be uplifting?

"I looked at all the gay films that were made and that had done well -- Philadelphia, Brokeback Mountain, Milk. Always someone dies in those films. There has to be some sort of somber attitude. There are some somber moments in our film, but ours is more of a celebration of being gay and coming out into the open. This is about street kids who don't care if they're being called gay. They just hate that they get beaten up, that society really is against them, and that their favorite clubs are being raided. They just want the simple freedom to be themselves."

Though many of the movies Emmerich references are populated by straight actors playing gay, he notes that many of the actors who played gay in The Boys in the Band were in fact gay themselves. He says casting should be blind to sexual orientation. "Some of our actors are gay, some aren't," Emmerich says, matter-of-factly. "That's progress."

After shooting an especially exhausting riot scene, Irvine explains his reasons for wanting to play Danny. "There are a lot of remakes being done right now. When I read this script I could see how original it all was. I wanted it so badly. I actually cried when reading it. When I was auditioning I was working with Colin Firth [on The Railway Man], who is in A Single Man, which is one of my favorite films. He said he had no qualms about playing a gay character. We're actors, and at the end of the day it's all make-believe."

The historical weight at the heart of Stonewall's script was intensely meaningful for the outrageously handsome Irvine. Tonight's scene calls for him to throw a brick and then scream, "Gay power!" at the top of his lungs.

After Emmerich yells cut, the scene is done. It took a few takes. Irvine looks up. He's in tears.

"I think I can be forgiven for crying after filming that scene," he says. "I think you can relate to anything through film. There were a few nights in 1969 when gays owned this street. That's what this movie is about."

In early August 2015, more than a year after visiting the Stonewall set in Montreal, the first trailer for the film was released. In short order, online publications and commenters accused Roland Emmerich of "whitewashing" the Stonewall story.

Emmerich responded on his Facebook page: "I understand that following the release of our trailer there have been initial concerns about how this character's involvement is portrayed, but when this film -- which is truly a labor of love for me -- finally comes to theaters, audiences will see that it deeply honors the real-life activists who were there -- including Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Ray Castro -- and all the brave people who sparked the civil rights movement which continues to this day. We are all the same in our struggle for acceptance."

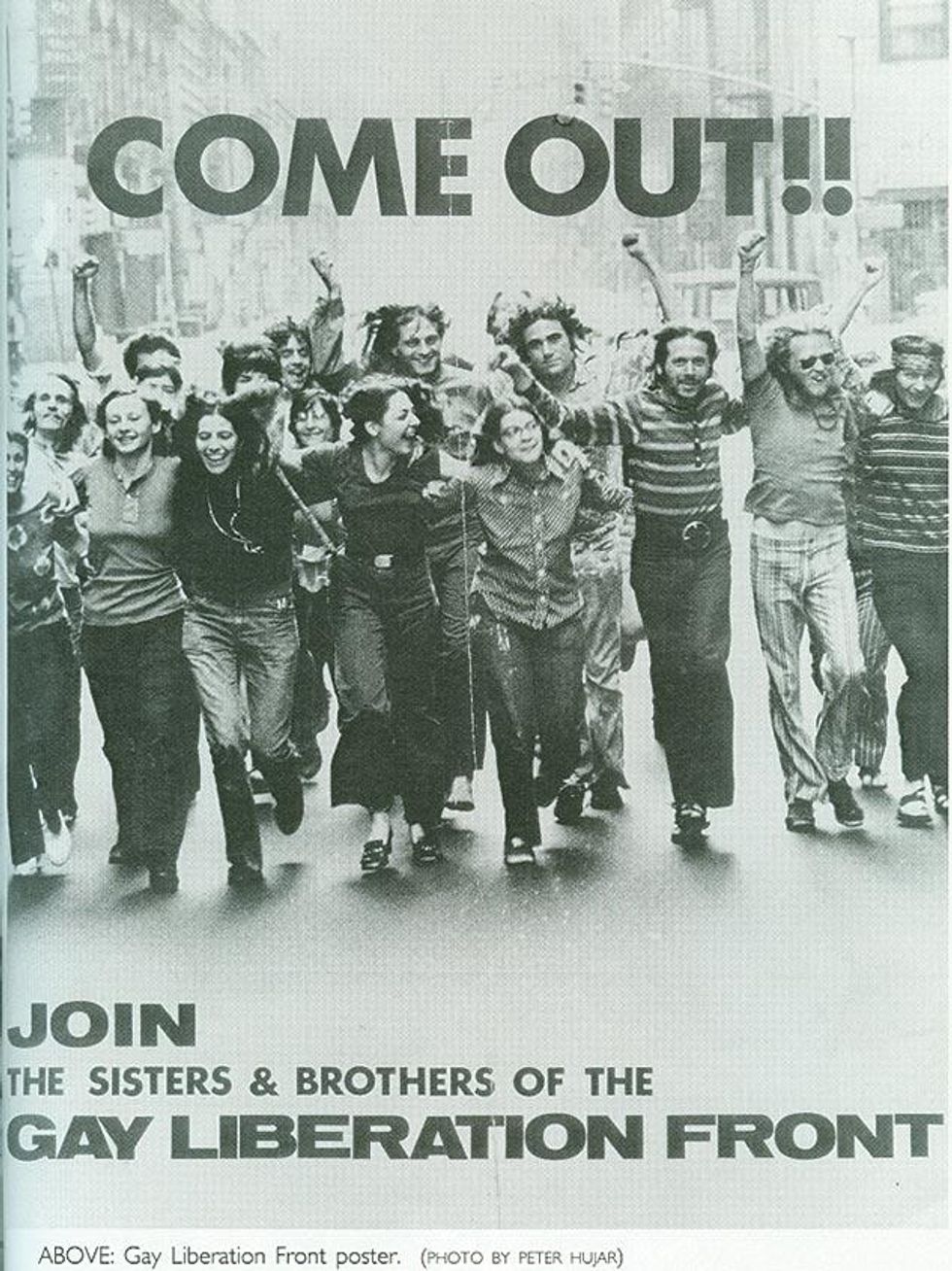

Peter Hujar is a photographer best known for his portraits, including the often-reproduced image of Candy Darling on her hospital deathbed.

But it was to mark the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising that Hujar shot this iconic image, which the Gay Liberation Front employed as a poster to recruit participants in the first Pride march in June 1970. Though he hoped to gather hundreds of subjects, only a handful were courageous enough to attend the early morning shoot in the Flatiron neighborhood of Manhattan. Undaunted, Hujar mounted the pedestal of a lamppost and directed his subjects to charge at the camera, and in the resulting image--which was papered on buildings throughout Greenwich Village and which read, "Come out! Join the sisters and brothers of the Gay Liberation Front" -- those 18 people have the might of an army.

Fran Winant, one of the participants, told The Gay & Lesbian Review, "As a measure of our success, no one now can know the fear we felt then at being in this photo and the poster made from it. Each year millions celebrate gay liberation with us. I imagine them filling the empty space in the photograph behind us."

While very few photos of the Stonewall riots exist, Hujar's iconic image resonates with the uncompromising spirit, rage, and hope of a burgeoning civil rights movement. --Matthew Breen