CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Secretly, Kalup Linzy wanted to totally queen out the second he spotted Criminal Minds star Shemar Moore on the red carpet at the Daytime Emmys. If the performance artist turned soap star had his druthers, he would have jumped up and down and squealed with joy.

Instead, he held back. "At that moment, I thought, Don't get too gay, chile!" drawls Linzy, hyper-aware that E!--which was broadcasting live--could catch him in the background drooling over the hunky actor better known for his role on The Young and the Restless. "I had to take it down a notch. I thought I was going to have an anxiety attack."

Linzy should have worked it. As the night wore on, he saw how the broadcast is produced for the audience at home rather than those attending in person. "Everyone knows each other," he marvels. Realizing that suddenly made the vast daytime TV universe, which the rural Florida native had grown up watching religiously, come down in size.

"I was like, Oh, this is the art world. These worlds are so small," he explains. "But when they get amplified in the media, they get really blown up. I should have just taken all the fucking pictures I wanted to take."

But he'll be back. Those tiny spheres of art and soap operas, different as they are from each other, have at least one thing in common: They've taken a shine to Kalup Linzy (his first name is pronounced KAY-lip). The art school-trained performance artist got his start making underground videos inspired by his passion for soaps, a love of the works of Andy Warhol and John Waters, and a burning desire to explore theories of race, class, gender, and sexuality. "A star is born," declared The New York Times in 2005.

His breakthrough piece was All My Churen, a semi-autobiographical series of videos that send up soaps and Southern black culture, in which he played all the roles, including women named LaQuavia and Labisha. Linzy's conceptual bent caught the eye of James Franco, the only young Hollywood A-lister to boldly toy with sexual identity as well as the bounds of art and commerce. Franco's stardom, his connections, and his own offbeat performance art persona -- the aptly named Franco -- helped catapult Linzy from gallery darling to General Hospital guest star, playing his alter ego, Kalup Ishmael. In one of his episodes, Ishmael sang "Route 66" onstage at a nightclub to an audience of Port Charles's youngest and hottest, which left the television outsider starstruck and unnerved.

"I blanked out a couple times, and you don't get that many takes," he says. "A lot of [the actors] have been on other soap operas, so I was like, This is insane."

With work in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum as well as a Guggenheim fellowship, a Jerome Foundation fellowship, and a Creative Capital grant to his credit, perhaps it's time for the one-of-a-kind artist's self-esteem to catch up with his success. "I'm always trying to figure out how to love myself more," Linzy admits.

He and his unlikely pal Franco have been collaborating on an amorphous set of projects, culminating, for now, in a much-heralded new EP of songs, titled Turn It Up. "I was surprised that so many people responded...the way they did," Linzy says. "I thought it was going to be this underground thing, and I was seeing [it announced] across the bottom of the TV screen. I wanted to shoot myself."

The end result isn't at all what the two had envisioned. Conceived as a full-length album on which Franco would sing extensively on songs written by the duo, the record instead features the Hollywood actor's spoken-word recitations and some snippets of his singing, which Linzy snuck in from samples Franco sent him. The star's busy schedule made for a piecemeal collaboration, but he shot video to accompany a few of the songs, including the playfully trippy "Rising (Both Sides Now)," the first release from Kalup and Franco.

"He contributed more than he thinks he contributed to it," says Linzy. "It's a full-on role, but since it was done over a long period of time, and in many pieces, in his mind it's probably like..." Linzy's words trail off, but his facial expressions say the rest -- that Franco would dismiss his own role in the project as minimal.

For a conceptual artist, Linzy doesn't always seem adept at articulating his own concepts; he frequently leaves his sentences unfinished. Sitting with the 34-year-old in a cafe in Brooklyn's Crown Heights, the recently gentrified area where he lives, you get the sense that Linzy's brain waves fire too quickly for him to form complete sentences. Halting phrases are dotted with expressions such as "like" and "you know" as well as leaps to entirely different thoughts. But when he talks about freedom, Linzy becomes downright eloquent.

"I want to explore and work in a space and do stuff that will inspire freedom. Not just freedom in terms of laws, but freedom, I guess, within myself," he says. "Freedom is an interesting thing, like, freedom to be alone, freedom to be in the types of relationships you want to be in, freedom to express yourself, freedom from fear. I don't always like being gay, and I don't always like other gay people. People might not want to hear that, but it's my truth. There are things I've been taught to hate. Do you find freedom in being more flamboyant? Do you find freedom in not communicating, going off into your own hole, and not being bothered?"

These are the thoughts that drove him to become an artist, but Linzy didn't know what being an artist meant while growing up in Stuckey, Fla. He was raised by his grandmother after his parents split up. He spent weekends and summers with his father, a farmer who was often off with migrant workers, picking apples up north. When Linzy was 12, his father had a stroke that left him paralyzed on one side of his body. Linzy's mother, he says, suffers from mental health problems and drug abuse, and she has been in and out of treatment facilities. Though his mother wasn't always in his life, an insurance agent came to his door when he was preparing to graduate high school to inform him that his mother had taken out a life insurance policy when he was a young boy. When his mother became incapacitated, Linzy qualified to receive $1,000, which helped him foot the bill for University of South Florida. "I knew she wanted me to go to college," he says. It also proved to him that she cared.

Once Linzy was away at school, becoming a performance artist was a natural evolution. He would lip-synch Erykah Badu songs for his friends at parties, often with a towel on his head. His audience said he reminded them of RuPaul, and they complimented his legs. "I wasn't paying that much attention to my legs until they said [that]," he says. "They planted some of those seeds. My career was not so much by accident but by interest and response."

Which is pretty much how it has progressed. The performance artist met Franco when the actor and perpetual grad student crashed a Linzy speech at Columbia University. "I was giving a talk there about soap operas," Linzy says, switching into a grande dame voice, "about my undying love of soap operas!" Franco was about to do General Hospital, and he pitched Linzy to the producers.

Not everyone gets Linzy's work. "My family liked All My Churen," he says, "but the more perverse I got, the less they like it in the art way"--that is, with the depth of interpretation that someone schooled in art might bring to it. "I don't always know if mainstream gays appreciate the work. If I feel like people don't relate, I don't force them to. I just don't share it."

But the General Hospital writers understood Linzy's strange appeal, though "they knew that only so much of it could work on TV," he says, laughing.

Not only was it a glam experience ("I had my own dressing room!" Linzy says), it brought his oeuvre to a level that would have impressed his father, who passed away without seeing any of Linzy's work.

"He was older; he didn't have a computer," Linzy says. "All he knew was that I played the piano in church and I grew up singing on his porch."

Linzy and his grandmother were longtime CBS soap watchers, but he was informed about the goings-on in Port Charles because his father was a lifelong General Hospital fan.

"Men watched soap operas because women did, whenever they were home," Linzy says.

Landing on that soap was therefore particularly meaningful, Linzy says: "I thought he must have been looking out." And the Daytime Emmys were the capper because this year's ceremony, in Las Vegas, took place on Father's Day.

"I kind of kept missing him..." Linzy says. "I was like, I'm going to the Daytime Emmys. I wish I could just go see my father, but I'll just go be starstruck."

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

31 Period Films of Lesbians and Bi Women in Love That Will Take You Back

December 09 2024 1:00 PM

18 of the most batsh*t things N.C. Republican governor candidate Mark Robinson has said

October 30 2024 11:06 AM

True

After 20 years, and after tonight, Obama will no longer be the Democrats' top star

August 20 2024 12:28 PM

Trump ally Laura Loomer goes after Lindsey Graham: ‘We all know you’re gay’

September 13 2024 2:28 PM

Melania Trump cashed six-figure check to speak to gay Republicans at Mar-a-Lago

August 16 2024 5:57 PM

Latest Stories

Sin City sinners: Jonathan Van Ness says 'Queer Eye' cast gets spicy in season 9

December 18 2024 5:48 PM

Bragging Trump gets ignored at his own golf club, and the internet roasts him

December 18 2024 5:30 PM

Chick-fil-A is working with an LGBTQ+ charity as it attempts to launch in the UK yet again

December 18 2024 4:20 PM

Senate passes defense bill with anti-trans language; now goes to Biden

December 18 2024 2:57 PM

Here are the world's most visited cities and where they stand on LGBTQ+ rights

December 18 2024 1:54 PM

Sarah McBride gives moving farewell speech to Delaware Senate as she heads to D.C.

December 18 2024 1:31 PM

Why Laverne Cox says she won't debate transgender rights

December 18 2024 12:21 PM

Johnny Sibilly pulls back the sheets on dating OnlyFans star Phillip Davis

December 18 2024 11:32 AM

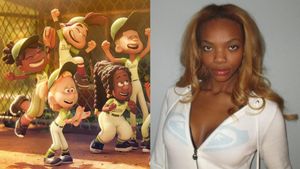

Chanel Stewart reacts to Disney cutting trans storyline from 'Win or Lose'

December 18 2024 11:17 AM

Scissoring secrets: Queer adult content creator Electra Rayne tells all

December 18 2024 10:00 AM

Gayest moments in Sabrina Carpenter's 'A Nonsense Christmas' special

December 17 2024 9:18 PM

Tammy Baldwin, 20 other senators try to strike anti-trans provision from defense bill

December 17 2024 6:46 PM