I first encountered Alan Chambers when I was 15. I stumbled upon his story on the website of Exodus International, the largest "ex-gay" organization at that time, when I was researching how to address my sexuality. I had just come out, naively so, to my religious community. As swiftly as I came out, I was dismissed. I saw so-called reparative therapy as a solution to my problem. I believed reparative therapy would allow me back into the folds of my religious community when it "healed" me of my bisexuality.

That was all a lie.

Reparative therapy is fabricated on the idea that being queer is innately disordered. That somehow we, as queer children of God, are less than our heterosexual siblings simply due to who we are. Chambers used his story of being married to a woman to perpetuate this lie. For that, I hated him before even meeting him.

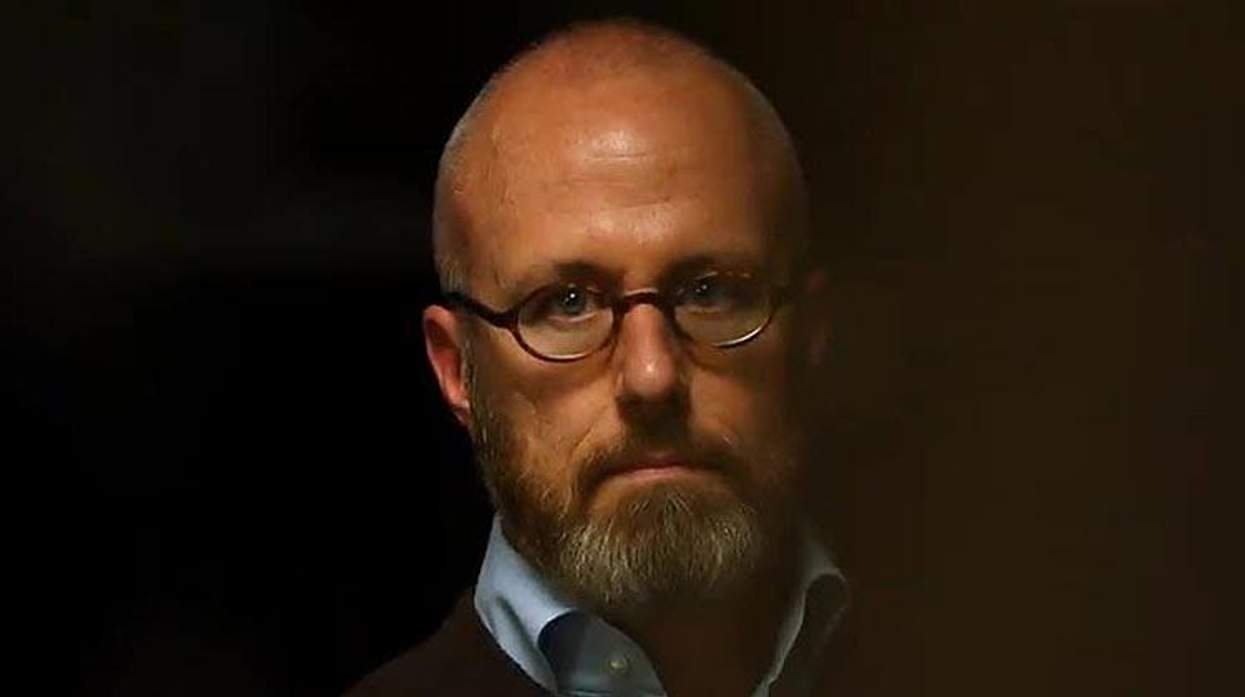

Years later, Chambers apologized for the damage he caused. I reached out to him to thank him for apologizing and we became online friends. I've emailed and chatted with Chambers numerous times since his apology, discussing the remnants of the reparative therapy movement.

That's why, when Chambers announced his book My Exodus: From Fear to Grace, I wasn't so quick to condemn it. While many LGBT people just wanted him to go away, I wanted him to fight against the ripple effect of his work. I saw this book as an opportunity to make amends. This was his chance to discuss all the ways he was wrong and to dedicate himself to expunging the fringe groups who still use his work against LGBT people.

Disappointingly, My Exodus did not do any of that. My Exodus failed in paying reparations to the LGBT community.

It's clear Chambers is still evolving. In my interview with him, he told me he believes same-sex relationships can be holy. A lot of his perspectives have changed in just the two years since Exodus has closed. I'm certain more will change as time passes.

In his book, Chambers discusses his journey at length. None of it is particularly new to those who already know his story. He's given his testimony hundreds of times during his time at Exodus International. Chambers began his journey as a young Christian teenager fighting his homosexuality and found his way to Exodus, through an Exodus affiliate known as Eleutheros.

He married his wife, Leslie, after falling in love with her -- the only woman he says he had any attraction to. The two used their story as a model for thousands of queer Christians looking for a solution to their sexuality. After two decades involved with Exodus International, Chambers infamously said that reparative therapy doesn't work for 99.9 percent of people. It was with those words that he closed the doors of the largest ex-gay organization in the world.

In My Exodus, Chambers describes his role in the promotion of reparative therapy as if he had no choice. Chambers seems to have gotten on a reparative therapy train that he simply couldn't get off. He describes himself as almost an innocent bystander in reparative therapy's promotion. Yet Chambers was not only on that train, he was its conductor as the president of the largest ex-gay group in the world.

This recounting of his story depicts Chambers in a favorable light. Many still see Chambers as a villain, intentionally out to destroy the lives of LGBT youth. Anyone who meets Chambers knows that's not at all the case. However, intent doesn't matter. While Chambers may not have been purposefully out to drive LGBT people to self-shame and eventually suicide, that is exactly what his work did.

This self-shame was around being gay -- something that Chambers still won't call himself. In the chapter "My True Self," Chambers discusses his sexuality. Or, rather, he doesn't discuss his sexuality. Although he believes everyone has a sexuality, he will not label himself, opting to say his orientation is geared toward his wife, Leslie.

It's evident that Chambers is wrestling with labeling his sexuality. In his book, he goes back and forth from calling himself a gay man to saying he does not want to identify himself as such. His refusal to label himself as gay -- or bisexual -- is a politically motivated choice. Chambers still needs to honestly address his sexuality. More than likely, he is a gay or bisexual man. His choice to remain ambiguous appeases a religious conservative audience.

Indeed, the majority of his book serves more as an explanation to a religious conservative audience. Chambers's book prioritizes addressing religious conservatives rather than the concerns of LGBT people. To address those concerns, Chambers should have labeled his sexuality, dedicated himself to outlawing reparative therapy, promised to respond to the religious communities that still use his work, unquestionably admitted his role in the promotion of reparative therapy. Additionally, he should dedicate a portion of his book proceeds to LGBT organizations.

Those are just a few of the many ways that Chambers could have paid restitution to the LGBT community.

I candidly told Chambers about my disappointment with his book. I told him the book did not achieve what I wanted it to achieve. He told me that those concerns could perhaps be addressed in "the next book." I did not wait 10 years for Chambers to apologize only to have to wait for these concerns to be explicitly addressed in the next book. My Exodus, while impactful for conservative Christians, does nothing for the LGBT people Chambers spent decades hurting.

ELIEL CRUZ is a contributor to The Advocate on bisexuality. He interviewed Alan Chambers for his column on faith and sexuality at Religion News Service. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

ELIEL CRUZ is a contributor to The Advocate on bisexuality. He interviewed Alan Chambers for his column on faith and sexuality at Religion News Service. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

ELIEL CRUZ is a contributor to The Advocate on bisexuality. He interviewed Alan Chambers for his column on faith and sexuality at Religion News Service. Follow him on

ELIEL CRUZ is a contributor to The Advocate on bisexuality. He interviewed Alan Chambers for his column on faith and sexuality at Religion News Service. Follow him on

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes