Society

Years After His Tragic Death, This Gay Adventurer Is Making History

Skydiver Donald Zarda's lawsuit against his employer could finally make antigay workplace discrimination illegal.

March 12 2018 5:06 AM EST

trudestress

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Skydiver Donald Zarda's lawsuit against his employer could finally make antigay workplace discrimination illegal.

Donald Zarda lived a life of adventure and accomplishment, excelling at electronics and technology, jumping out of planes and off cliffs, and teaching his skills to others. But his greatest accomplishment came in advancing LGBT rights, and it's one he didn't live to see.

Zarda was fired from his job as a skydiving instructor by Long Island-based Altitude Express in 2010 after telling a client he was gay. The company claimed there were other reasons for his dismissal, but he sued, saying his employer discriminated against him because of his sexual orientation. After he died in an accident in 2014 at age 44, his estate continued to pursue the case, and last month it resulted in a significant ruling from a federal appeals court that existing civil rights law against sex discrimination covers sexual orientation as well.

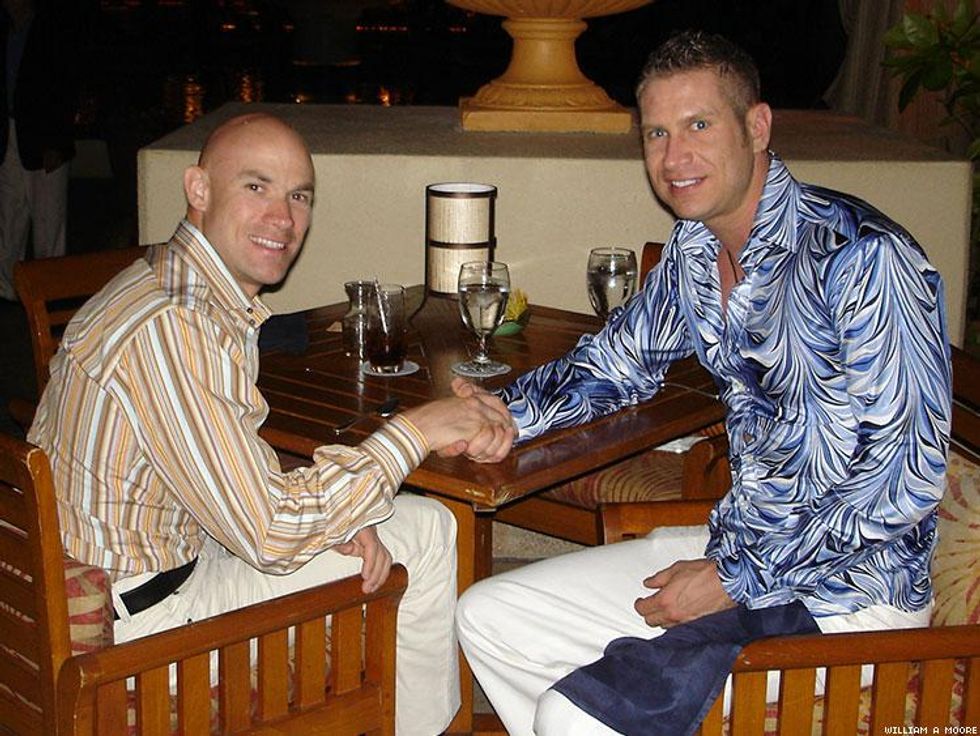

"He would be so proud that he had any input into something this large for our community," says William Allen Moore, Zarda's partner and coexecutor of his estate. "This is the most important thing he has done in his life.

"Don would be overjoyed," says Melissa Zarda, his sister and the other coexecutor. "This case was such a burden to him. I just wish he was here to see that it was all worth it."

There was never any hesitation that they would continue with the case. "I knew immediately that I would," says Moore. "I don't think for either of us there was any question."

Melissa Zarda corroborates that. "This case was very important to him, so I felt I owed it to him to pursue it in his honor," she says.

They're honoring a man they remember as adventurous, intelligent, funny, and determined. Donald Zarda grew up in Missouri, the third of four children, and his abilities were evident from an early age.

"He was incredibly gifted," Melissa Zarda rccalls. "He was always years ahead of other kids in his age group -- wiring stereo equipment or designing custom electronic gadgets. I believe it was in middle school that he rigged a stereo complete with a CB radio on his 10-speed bicycle, and when he turned 16, he designed electronic controls for special Knight Rider-style lights on his first car, a Datsun.

"Honestly, I'd say Don was a nerd -- and I mean that as a compliment! He had a knack for mapping out complex schematics and applying them to whatever custom project he'd be working on at the time. With the dawn of the computer age, it was only a natural progression that he would end up studying engineering and IT."

Another sister, Kimberly Zarda, shares similar memories (a third sister, Gara, died in 2008). "From a very early age he was interested in electronics, how things were wired, where does electricity come from, what makes a light bulb provide light or a radio make sound," Kimberly says. "And that inspired him to learn more, eventually becoming an electrical engineer. He always had a phenomenal stereo and speakers. As the internet age took off he became an expert in IT and networking. He could wire anything."

But he wasn't all work and no play. "Don's sense of humor really stands out" as a memory, says Melissa. "He'd say something funny and immediately launch into his trademark giggle."

But he was indeed good at anything he did, adds Moore, including not only electronics but performing laser hair removal at Moore's Dallas medical spa, where he often worked in the off-season for skydiving -- and, of course, skydiving.

He was introduced to skydiving while in military school and fell in love with it. "He excelled at almost everything he ever attempted, and skydiving was no exception," Kimberly recalls. "The motivation to become an instructor appeared when he realized that maybe he could actually make a living doing something that exciting and exhilarating."

He worked at various skydiving companies around the country, and in 2000, he was on his way from one in south Texas to see his family in Missouri when he stopped in Dallas. At a bar there, he met Moore, and soon afterward they began a relationship -- Zarda's only romantic relationship, Moore says.

Their meeting was the result of one of those small decisions that make all the difference in a person's life. Interstate 35 splits into eastern and western portions in the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area, and the two portions rejoin north of the cities. Zarda chose the eastern portion, which took him to Dallas.

The two men lived together in Dallas when it wasn't skydiving season, and they had many cats -- Zarda was an animal lover -- and were active in the local LGBT community, going to the Human Rights Campaign dinners in town and donating to LGBT and HIV organizations.

Zarda had long been out to his family, and his sisters say his sexual orientation was never controversial. His coming-out "was basically a nonevent," Melissa recalls. "He told me when he was back in town for a visit and he took my cousin and I out to lunch. He was in good spirits and let on that he had some huge news to share. He told me he was gay, and I was like 'Cool. So anyway, how long are you in town?' Looking back, I think he was probably hoping for at least a little more fanfare than that."

"I don't remember our family really having that big of a reaction when he came out," Kimberly adds. "He was my brother, a son, a nephew, and we loved him regardless. If anything, I felt compassion for any pain he may have suffered for feeling that he needed to keep that side of him concealed."

As a skydiving instructor, he generally told his women clients he was gay, to ease any discomfort they might feel about being strapped to him during a jump. But his honesty backfired in 2010, when one client complained -- and he was fired.

His company gave other reasons for the firing, at one point saying Zarda had touched a female client inappropriately, Moore says. He adds that Zarda, who prided himself on his professionalism, would never do such a thing. Zarda was extremely careful with clients and only had one accident throughout his skydiving career -- injuring himself -- but he never injured a client, says his lawyer, Gregory Antollino.

Losing his job, especially under those circumstances, was traumatic for Zarda, according to his partner and sisters. "He was a wreck," Moore recalls. He felt he couldn't get hired anywhere else, and he lost interest in pursuing his college degree, having interrupted his studies some years earlier.

"He was worried about his future, and he wanted his name cleared," Antollino adds.

Zarda also became more heavily involved in BASE jumping, an activity that's more dangerous than skydiving -- so dangerous, in fact, that it's illegal in the U.S. It involves jumping off a fixed structure with a parachute or in a wingsuit. "BASE" is an acronym for the four types of structures used -- building, antenna, span, and Earth, the last one extending to cliffs.

"He was an adrenaline junkie," Moore says of Zarda's attraction to both skydiving and BASE jumping. When Zarda went to Switzerland for what would be his final and fatal jump, Moore had a bad feeling. "I knew, when I dropped him off [at the airport], for some reason, that I wasn't going to see him again," Moore says. But he knows that Zarda "died doing what he loved," he adds.

The Second Circuit ruling isn't the final word on his case. The court ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, by banning sex discrimination, applies to sexual orientation discrimination as well, but it didn't rule on the merits of Zarda's case, that is, whether such discrimination actually occurred, Antollino explains. So the trial court could reconsider the case with that in mind, or there could be a settlement. Or Altitude Express could appeal the finding on Title VII to the U.S. Supreme Court.

A three-judge panel of the Second Circuit, based in New York City, had dismissed Zarda's appeal in April of last year, saying Title VII didn't apply. But the full court agreed to rehear the case after the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit became the first federal appeals court to rule that Title VII covers sexual orientation, and the second time around, a majority of Second Circuit judges agreed that it did. The Sixth Circuit recently ruled that Title VII covers discrimination based on gender identity.

Since it's just these courts that have ruled for a broader interpretation of Title VII, it's not the law of the land, although it sets a precedent for those circuits. The Obama administration and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal agency that has a degree of independence, interpreted it broadly as well. The Trump administration has embraced the opposite view, and the Justice Department even argued in Zarda's case that Title VII didn't apply.

But even though it hasn't changed the law nationwide, the Second Circuit ruling is a significant step forward for LGBT rights. The Supreme Court upholding this interpretation of Title VII would be a national victory, although it may wait to take a case on Title VII until more federal appeals courts have ruled, as it did with marriage equality.

In December it declined, without comment, to hear the appeal of a Georgia lesbian who brought a suit for discrimination under Title VII when she was fired from her job; an appeals court had ruled that Title VII didn't cover sexual orientation. When the Supreme Court declined to hear her case, Lambda Legal attorney Greg Nevins said the justices were simply "delaying the inevitable." A high court ruling may come more quickly than congressional action to ban anti-LGBT discrimination, especially with Republicans controlling Congress and the White House.

For now, Zarda's loved ones and his lawyer are glad he played a role in advancing LGBT rights, and they're hopeful about the future. "I want [his action] to be long-lasting for the LGBT community," says Moore.

"I was surprised" by the verdict, Melissa Zarda adds. "I was worried that with the current administration and in this political climate, we'd have a hard time pursuing an appeal. It has been explained to me how rare of a ruling of this nature really is and how it is a great victory. I hope that this case continues to challenge outdated precedents so that someday soon all LGBTQ citizens are federally protected in the workplace."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes