For openly gay former major leaguer Billy Bean, the decision to walk away from baseball was painful. But what he didn't know would be how long that pain would last. He didn't know how much the decision would affect his family. He didn't know how to grieve openly for the man he secretly loved, following his death. He just knew he couldn't be closeted in pro baseball anymore. So he just left.

"I played baseball for 23 consecutive years of my life up until that point," Bean says. "I thought if I just took myself out of that environment that I felt so isolated in, it would fix everything, but it really compounded that, and it was a harsh lesson to learn."

Bean's decision 20 years ago eventually pushed him to become an advocate for any openly gay player who would follow in his professional footsteps.

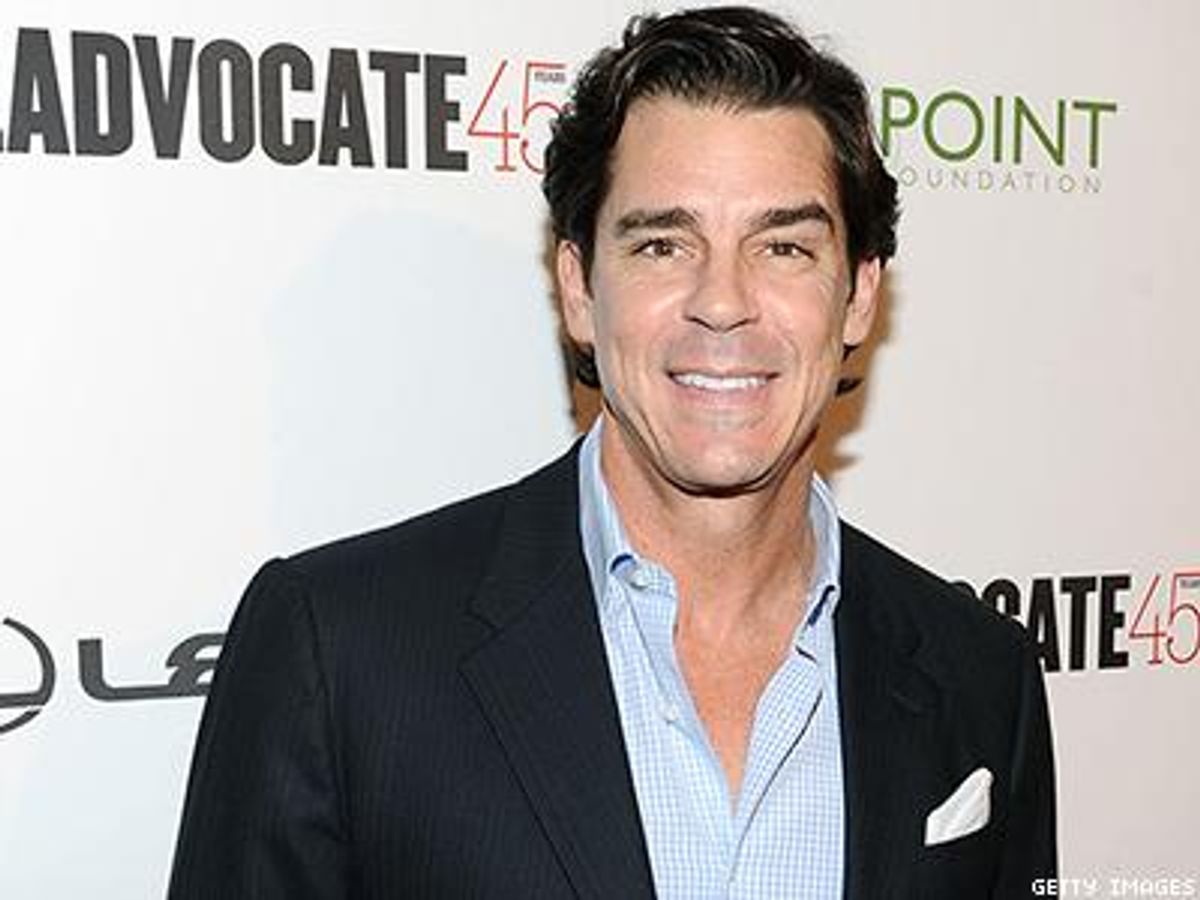

Now, he is back at work with the league -- this time in a suit. This summer at the MLB All-Star festival, Bean was named the Ambassador for Inclusion for major league baseball. His new position will require him to work with the 30 clubhouses across the country, and each of those teams' seven minor league teams, to usher in a more welcoming environment for players and executives in terms of gender, race, and sexual orientation.

When commissioner Bud Selig announced Bean's appointment this summer at a press conference during the All-Star festival, Bean says he had been "preparing for this for the last 15 years." The day Bean had learned that his partner died due to complications with HIV in 1995, there was no time to grieve. No one knew he even had a male partner. He had to play baseball that night. But quickly thereafter, he quit the game. Bean says the pain of leaving the sport he was so dedicated to, and losing his partner was like experiencing death twice. It was the type of pain he says no one should ever have to endure.

"I lost my partner, and then I left baseball," he says. "The two things that were so dominant in my life were both gone."

When did Bean, who played from 1987-1995 for the Detroit Tigers, Los Angeles Dodgers, and San Diego Padres, realize he may have made a mistake in leaving? He says 10 minutes after watching the first spring training baseball game he didn't get to play in. But since then he's come out, written extensively about his time in the major leagues, and has become an advocate for LGBT athletes, from hockey to swimming. He says it's been helping him heal, and so is his new job.

The fascinating part is how much the league has changed since his days in the clubhouse. In his near decade in the major leagues, Bean says he was never been actively discriminated against by teammates because he was closeted. That didn't stop the homophobic remarks being thrown around the locker room.

"It's because that was allowed," he says. "Nobody ever thought there were any gay [players around them], I guess, at the time. But I heard many stories from my teammates, especially coming up in the middle 80s, [about] discrimination in the south against African-American players, Latino players hearing, 'speak English or get out,' you know."

These days, however, the league's offices look different. "Now, you have female trainers, and LGBT reporters, and all kinds of executives," he says. So far, he's been working closely with Wendy Lewis, the SVP of Diversity and Strategic Alliances for Major League Baseball, and an African-American woman.

"Sexism is wrapped in every homophobic remark," he says. "Women in Major League Baseball were pioneers in pushing the envelope to be part of a world that they firmly were not made to feel welcome. I know that whenever a woman shares her story then she's teaching other women that this is possible. When an African-American woman shares her story, she's speaking to two groups."

Which is why Bean sees his role in the MLB as being so crucial to showing any gay players in the majors, the minors, or even in high school and college or overseas, that baseball has room for out players, executives, trainers, and managers. Bean is not only willing to share his story about his struggle to come out, but eager.

"I'm fearless now," he says. "I'll take that first stressful experience if it buffers it for the next guy. If there's someone in the clubhouse who is holding onto their secret, and they walk out onto the field a little bit stronger, a little more confident for that next game, and that gets him to next year and he's ready to come out, then that means I'm doing my job."