As Americans celebrated the Sunday institution that is pro football, unknown to all but a few is a hidden history of gay allies, players, and increasingly, out gay fans.

The advent of marriage equality, however, has not yet scored any significant victories, with zero additions of out players to National Football League team rosters, coaching staff and management since June. However, even the acknowledgement that gays can and should play -- as the New York Giants did in a groundbreaking video last year -- is a step forward for the NFL.

Because the truth is gays have, and most likely, do play pro football, while closeted.

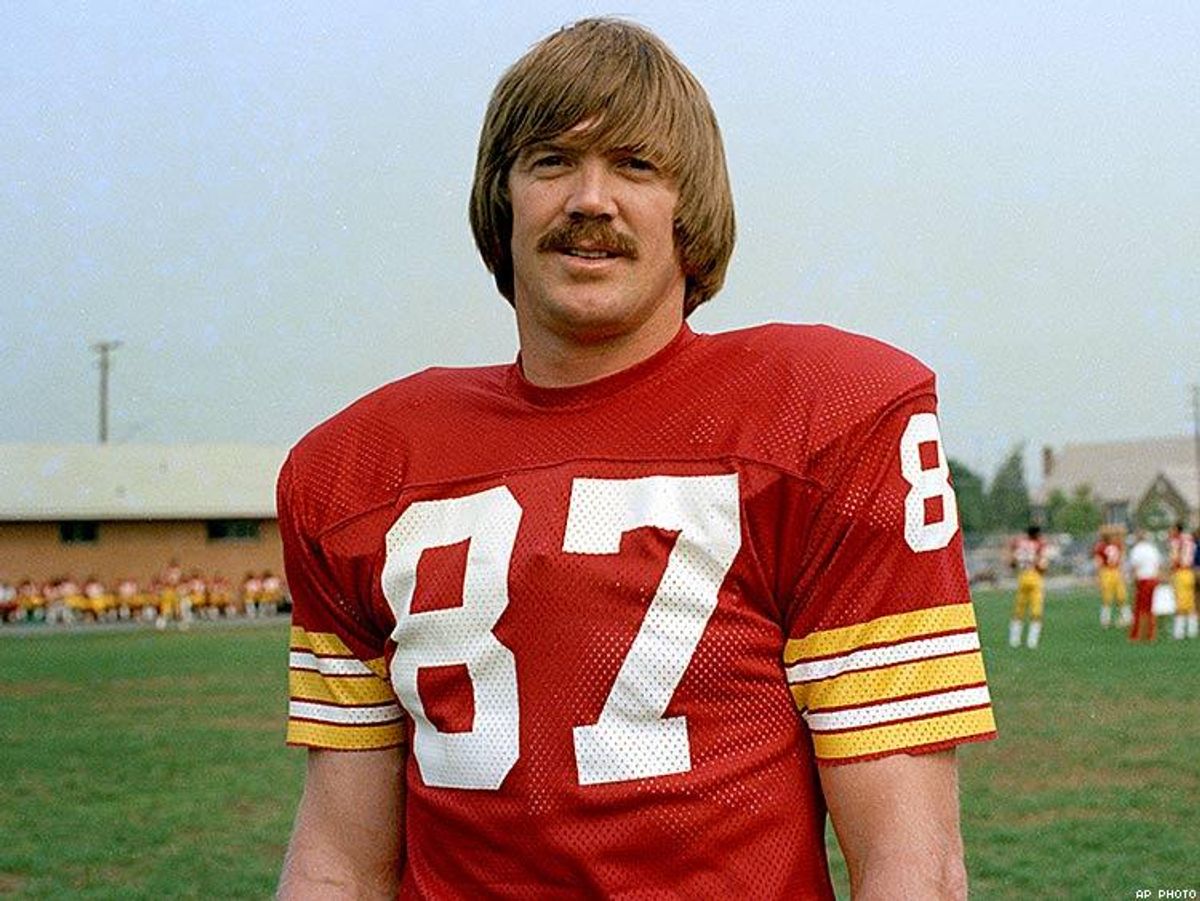

NFL fans are currently voting on the football heroes who will be named to the Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Not listed among the nominees to be chosen, yet again, is Jerry Smith. The two-time Pro Bowl tight end played for the Washington Redskins from 1965 to 1977, retired with 60 touchdown receptions, which established a record that stood for 27 years. He came out in 1986, a truly bold step for its time. He had contracted AIDS, and told the Washington Post he revealed his disease and his sexuality in hopes of making a difference.

"I want people to know what I've been through and how terrible this disease is. Maybe it will help people understand. Maybe it will help with development in research. Maybe something positive will come out of this."

Smith died three months later, and for years, fans and friends have campaigned for his contribution, courage and pioneering spirit to be recognized. He has been eligible since 1983 but has never made the finalists list, and according to Fox Sports, was named to the preliminary list only twice, in 1983 and 1987. Even in the seniors division, Smith has been nominated only one time.

"This guy was a tremendous football player. Tough as nails, great hands - just so dependable," said Bobby Mitchell in Jerry Smith: A Football Life, which debuted on the NFL Network two years ago next week.

Smith was a proven star who had 421 catches for 5,496 yards; that's more receptions than three tight ends now in the Hall of Fame, and only six fewer than Mike Ditka caught. Smith also surpassed three inductees in receiving yards. As GLAAD wrote in 2014 to herald that documentary about Smith, "Off the field, Smith lived with a personal secret he did not publicly share with his teammates."

It wasn't until long after his time on the gridiron that Smith acknowledged being in a relationship with Dave Kopay, who made history as the first professional team sport athlete to come out as gay. That was in 1975, three years after his retirement from a nine-year career as an NFL running back for San Francisco, Detroit, Washington, New Orleans and Green Bay.

Although Kopay attempted to transition to a coaching career, once he was out, no team would touch him. In 1998, he spoke to ESPN's Outside the Lines:

"It seems like the biggest fag-haters I've known are the people who are most confused about their sexuality. I know, because I was one of them."

"There are definitely gays in the front offices, and on the teams in the NFL. Gays have always been a part of society at every level; of course, in some areas they excel in greater than others."

"I think there's just not enough love, period, in the world. I can't understand why people get so upset with that expression -- unless, again, they are fighting their own fears."

And that was 1998.

You have to fast forward to 2014 to find another out player, Michael Sam, who was the first out player ever drafted by a pro team, the St. Louis Rams. But the Rams cut him, and after a short stint with the Dallas Cowboys practice squad, he was cut once more and never played in a single NFL game. Sam briefly joined a Canadian team, the Montreal Alouettes, but quit abruptly last year and announced he was retiring for fear of suffering mental health problems, a real danger highlighted by the new Will Smith film, Concussion.

But the other danger LGBT advocates and sports journalists say has kept pro players in the closet is the fear that they will lose support not only from teammates but from antigay fans who will in turn spurn their team.

"It always come back to fear," Outsports editor and co-founder Cyd Zeigler tells The Advocate. "Fear of the unknown. Fear of retaliation he might receive. The world of football revolves around this very macho image of what it means to be a man that we all learned as children, that being gay is the antithesis of what it means to be a man.

"I think consciously people understand every gay man is not a broadway show queen," says Zeigler. "But we still use 'straight' to say 'I'm good' and 'gay' to mean something is bad. 'That's so gay.' There is a subconscious understanding that goes back to messages we received in high school."

Zeigler predicts the next generation won't be the same, "It will only be the kids who are in peewee leagues today who will grow up without that. No child will ever be born into a culture where Michael Sam didn't exist, where (retired San Francisco 49ers offensive tackle) Kwame Harris didn't exist, where (retired offensive tackle) Esera Tuaolo didn't exist." Coming out didn't happen until after retirement for Harris and for Tuaolo, who played for the Carolina Panthers, Atlanta Falcons, Jacksonville Jaguars, Minnesota Vikings and Green Bay Packers during his nine year career.

Zeigler says it haunts him that a pioneer like Jerry Smith is not in the Hall of Fame.

"Last year at the Super Bowl, I spoke to a few voters for the senior committee of the Hall of Fame about Jerry Smith," Zeigler tells The Advocate. "The tight end is more valued today than it was then. He has a tough go of it," despite setting that record that stood more than two decades. "And the guy who broke his record is in the Hall of Fame," says Zeigler, referring to Shannon Sharpe.

"There is such a distinct difference in how coming out is accepted between men and women's professional sports," Zeigler says. "In women's soccer, we had at least 18 come out. In the WNBA, over a dozen players and coaches have come out. But on the men's side just Robbie Rogers," who plays for the L.A. Galaxy soccer team.

And of course, there's also the fear of losing all that money. The average salary in the NFL is $2 million, according to Forbes, and star players can make a million or more in endorsements.

"I imagine that might be a fear among some people," says Zeigler, "but it's an irrational fear. Michael Sam, all of those who have come out in pro sports, there are endorsement deals, even being out. In fact, coming out is seen as a positive. Corporations want to be associated with the values of coming out: courage, bravery, truth."

Perhaps pro football leaders, players and fans should look to the man who was the Moses of modern sportsmanship and a hero to generations: Vince Lombardi, whose brother, Harold, was gay, according to Yahoo! Sports, and believed strongly that discrimination against gay people was wrong, "just as he was angered when he saw mistreatment of his black players, or discrimination against his fellow Italian-Americans. "

Several players told NBC Sports Profootballtalk blog in 2013 that the legendary former Packers and Redskins coach knew some of his players were gay. "Not only did he not have a problem with it," wrote Michael David Smith, "but he went out of his way to make sure no one else on his team would make it a problem."

According to Kopay, Lombardi may even have known he and Smith were in a romantic relationship. "Lombardi protected and loved Jerry," Kopay told ESPNNewYork.

"If a coach who was considered old-fashioned even by the standards of the 1960s accepted gay players in his locker room," wrote Michael David Smith, "the idea that gay players couldn't be accepted in an NFL locker room in 2013 is both silly and sad."

And in 2016, Jerry Smith is still not going to the Hall of Fame, no out players are competing for the Super Bowl, and LGBT football fans will have to wait for the next hero like them.