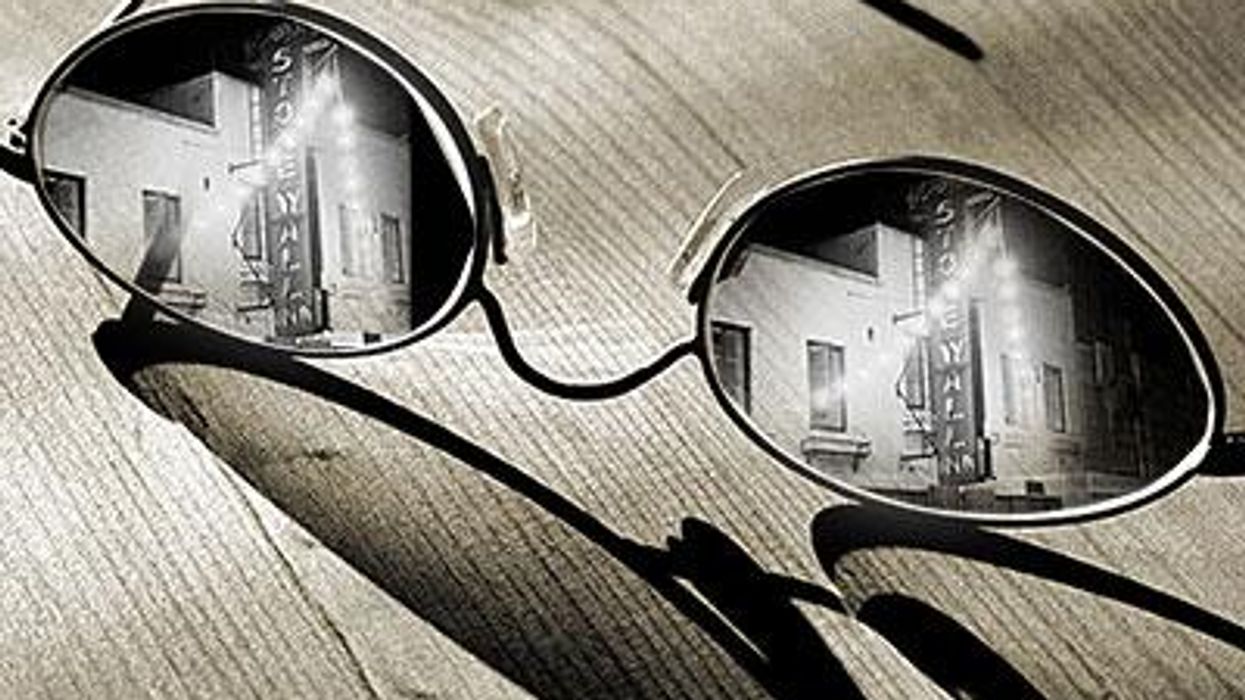

With today marking the anniversary of Stonewall, we take a look at some of the people who participated in the riots and how Stonewall shaped their lives.

June 28 2015 4:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

With today marking the anniversary of Stonewall, we take a look at some of the people who participated in the riots and how Stonewall shaped their lives.

The riots at the Stonewall Inn, which began in reaction to a police raid in the early morning of June 28, 1969, are generally credited with launching the modern LGBT rights movement and paving the way for momentous strides in equality, like this week's Supreme Court ruling legalizing marriage equality. Although it was actually one of several important uprisings, it was a very significant one, and it's one we commemorate with Pride celebrations this weekend. Those celebrations, of course, will be all the sweeter because of Friday's Supreme Court rulling for marriage equality. "For those of us who were there, we never dreamed that this day would come," said Stonewall veteran and Philadelphia Gay News publisher Mark Segal in an email Friday. "We welcome it with a sense of pride and joy." Here we look at a few of the others who were there for the uprising at the bar in New York City's Greenwich Village, their perspectives, and what they've done since. Some are still with us, some not.

Transgender woman Sylvia Rivera was dancing in the Stonewall Inn the night of the raid. "We were led out of the bar and they cattled us all up against the police vans," she recalled to Leslie Feinberg in a 1998 interview for Workers World. "The cops pushed us up against the grates and the fences. People started throwing pennies, nickels, and quarters at the cops. And then the bottles started. And then we finally had the morals squad barricaded in the Stonewall building, because they were actually afraid of us at that time. They didn't know we were going to react that way. We were not taking any more of this shit. We had done so much for other movements. It was time." Rivera continued for many years to be "a loud and persistent voice for the rights of people of color and low-income queers and trans people," notes a biography on the website for the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, named in honor of Rivera, who died in 2002. The group "works to guarantee that all people are free to self-determine their gender identity and expression, regardless of income or race, and without facing harassment, discrimination, or violence." Its namesake recognized that Stonewall was a key event in the stuggle. "I am proud of myself as being there that night," she told Feinberg. "If I had lost that moment, I would have been kind of hurt because that's when I saw the world change for me and my people. Of course, we still got a long way ahead of us."

After Martin Boyce participated in the Stonewall riots, he went back to Hunter College in New York City for his junior year. The riots gave him the courage to do something he never thought he would. "I decided that all of my term papers would be gay," he recalled in the documentary Stonewall Uprising. "I can say now that that was a courageous thing to do because nobody would hand in a paper in 1969 that had those explicit themes. It just wasn't accepted." Boyce sees Stonewall as a pivotal moment in his life. "I was able to live my life, which I would have done anyway, but without Stonewall I would have had more opposition," he said in the film. "So it turns out the times were on my side, which left me with a basically happy life." He eventually trained as a chef and ran a restaurant in New York's East Village. "It was called Everybody's Restaurant and it was a meeting place for artists -- I had a gay business partner who was a painter. Our slogan for brunch, which was completely gay, was 'We treat our customers like kings because the owners are a bunch of queens.' The restaurant brought everyone together; it was totally integrated." Just this week Boyce, now 67, testified before the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in favor of making the Stonewall Inn a city landmark, a status the commission voted unanimously to grant. "Let's give our youths something," he told the commission, noting that there are few LGBT-related sites designated as historic landmarks, London's Guardian reported. Of the riots, he said, "It was brutal, but necessary. I'm glad I lived to see this. This is what we fought for, and we won our battle."

On the night of June 27, 1969, Raymond Castro was at Stonewall when the police arrived. While he was released by police shortly after being led out, he stood outside waiting for the others to be released. He saw a friend of his inside who did not have an ID, and he quickly got his hands on a fake ID and attempted to hand it to his friend, only to be pushed back into the bar by police officers and was held as if in "a hostage situation," he recalled in Stonewall Uprising. Later, while handcuffed and being led to a police van, Castro knocked down two officers. "I resisted arrest," he noted in the film. Castro said he "never ever gave it a thought of [Stonewall] being a turning point. All I know is enough was enough. You had to fight for your rights. And I'm happy to say whatever happened that night, I was part of it. Because [at a moment like that] you don't think, you just act." Castro died in 2010 at age 68; he had long lived in Florida and worked as a cake designer and baker for Publix supermarkets. He was survived by his partner of 31 years, Frank Sturniolo.

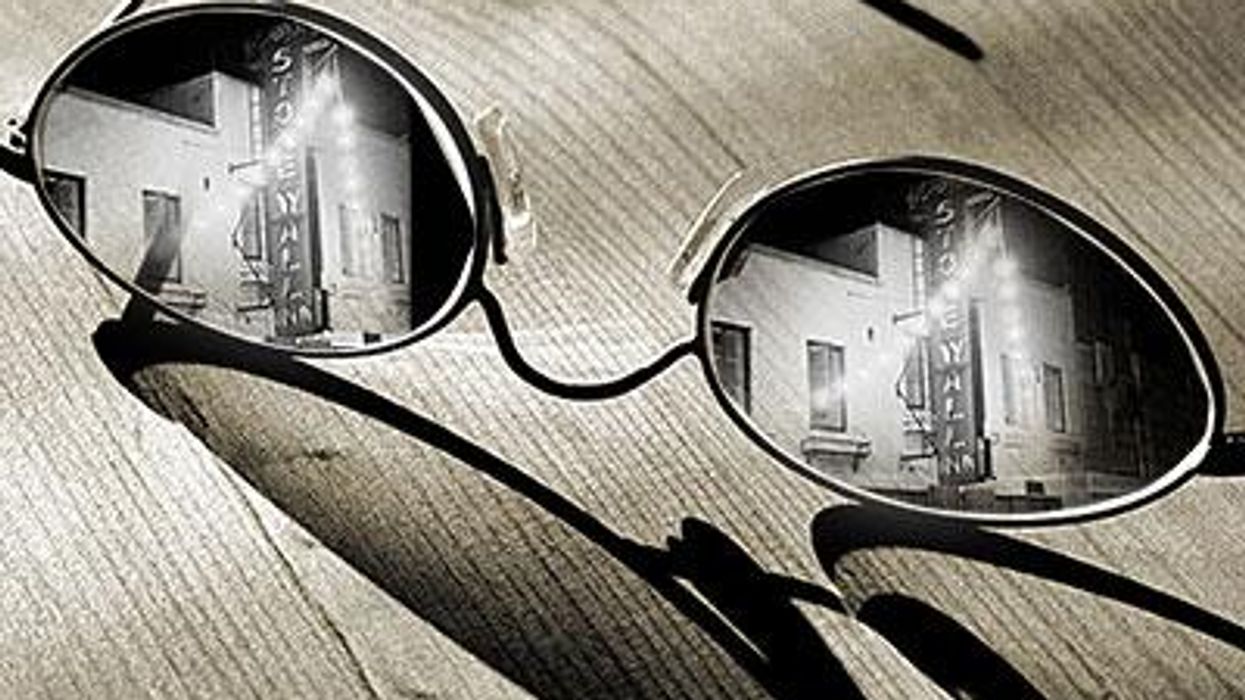

Danny Gavin was a 20-year-old hippie living in a gay commune in Greenwich Village in the summer of 1969. Of the Stonewall riots, he recalled to PBS, "You don't forget seeing Molotov cocktails being thrown and kids with blood coming down their faces," but the event didn't stand out to him until years later. "Bars were still raided after Stonewall," he noted. He was not in the club when the police raided it, but he was walking toward the bar with a friend when he saw the crowd gathered outside. "Danny was outraged by the gross injustice he was witnessing, but as a pacifist hippie, he did not participate in any violence," David Carter, author of Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution, wrote in a 2015 essay. "But he did join the crowds of protesters resisting police efforts to clear the streets so that they could bring the uprising to an end." Garvin's memories, Carter noted, were crucial to the book and the Stonewall Uprising documentary film. Garvin, who worked as a recreational therapist, became an AIDS activist in the 1980s and eventually also became involved in the recovery movement. He founded the Sober Together contingent for the New York Pride parade, which was one of the parade's largest. He died in December of last year.

Jerry Hoose

Jerry Hoose

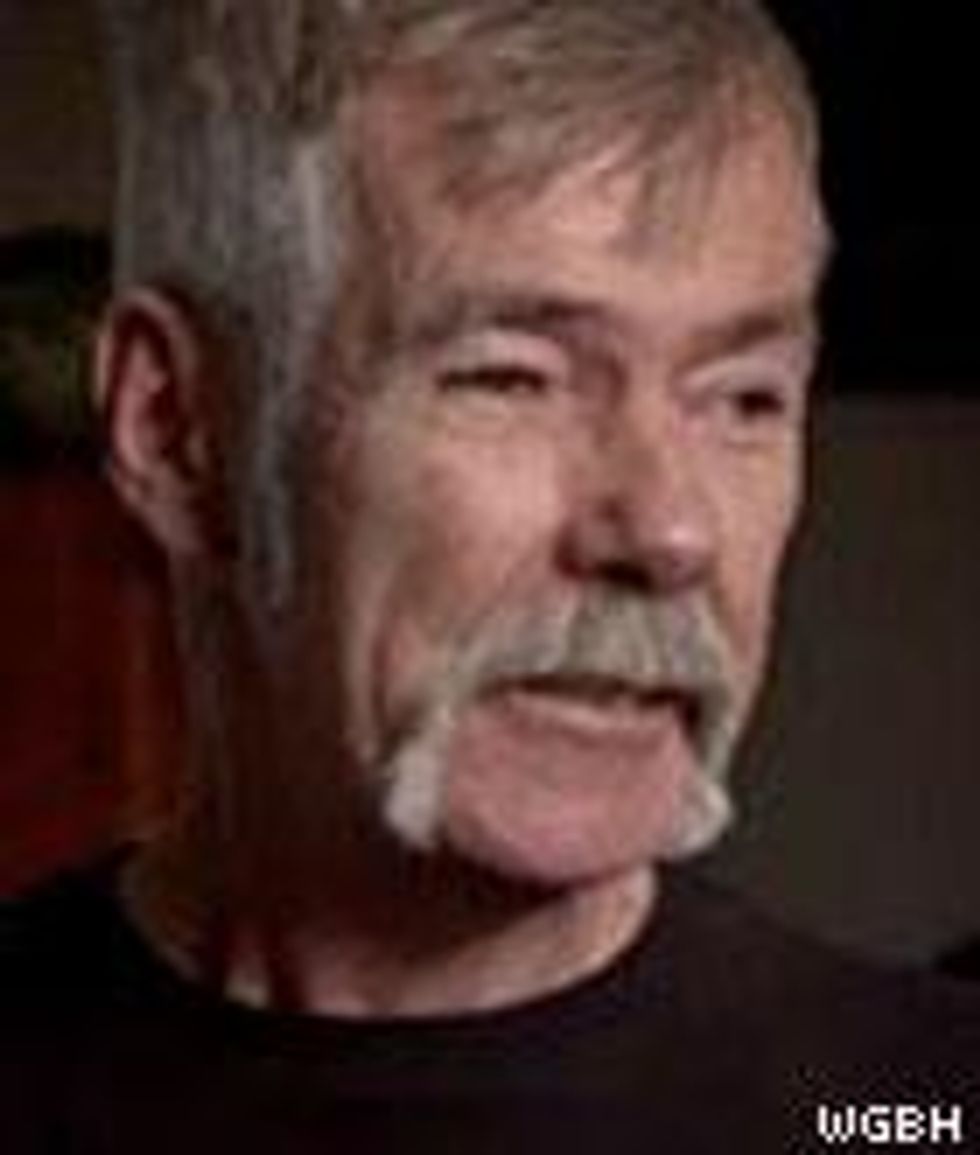

Marsha P. Johnson, known as "the saint of Christopher Street," may have actually started the Stonewall riots. In an interview for the 2012 documentary Pay It No Mind: Marsha P. Johnson, author David Carter recalled witnesses telling him "that Marsha Johnson said, 'I got my civil rights!' and then Marsha threw a shot glass into a mirror. And that's what started all the riots." He added, "When you look at the mythology, with the few known facts that withstand scrutiny, I do not think that there is any doubt that she was there the first night. And I think if we had to conclude, in all probability, that she was probably among the first to resist the police in a physical way." Johnson became an advocate for trans people, founding Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries with Sylvia Rivera -- the group often helped trans people find safe housing -- and was active in the Gay Liberation Front. She also was a model for paintings and photos by Andy Warhol. Johnson died in 1992.

Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt was a runaway from New Jersey who moved to the Village at age 17. After a year of living with other gay runaways, he decided to continue his studies at Cooper-Union and chose to write his entrance paper on being gay. He was denied acceptance and reported the incident to the American Civil Liberties Union. "I went to the civil liberties union and told them what happened," Lanigan-Schmidt said in Stonewall Uprising. "and they told me to see a psychiatrist. I had a breakdown over this. It was very traumatic." He found a gay community at the Stonewall, where he was a frequent patron and a participant in the riots. "The Stonewall was totally different because you could slow-dance together," he said in the film. "Holding on to another person without that fear that someone is going to bash you over the head is totally centering. So going to the Stonewall grounded me and then the Stonewall riots just brought that feeling out into the real world." Lanigan-Schmidt became an acclaimed artist and a professor at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he is still on the faculty. In a 2013 interview for the school's website, he described an essay he wrote on being a youth at Stonewall as "my greatest work of art, even though it's a written piece. It met with a wider audience and is about such a unique situation."

As the executive director of the Mattachine Society of New York, a gay organization, Dick Leitsch was familiar with riots and police raids. He covered the Stonewall rioting for the Mattachine newsletter. "I was the first gay person to write about Stonewall and I said it was the best thing that could have happened," he said in Stonewall Uprising. I felt like Lenin at the revolution, but it turned out that for Mattachine it was the beginning of the end. ... a week after Stonewall there were a thousand groups and each had its own agenda. Some people thought Mattachine should be more militant and others felt the people at Stonewall were just a bunch of dirty hippies and that nice boys didn't riot. It was hell." He left New York for a while, then returned to work as a freelance writer for a gay newspaper, but eventually left the movement, uncomfortable with how some things were being handled. But he recognizes that Stonewall and the gay movement created progress. "Every once in a while I'll walk into a gay bar and look around and see people being openly gay and being free to do what they want to do and I think to myself, 'I had a big hand in this,'" he noted in the documentary. "And I feel good about that."

Prior to Stonewall, John O'Brien was already an experienced activist, having joined the NAACP at age 13 and a peace group at 15. His experience at Stonewall and as a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, however, were transformative, he recalled in Stonewall Uprising. "What had been a small isolated gay rights movement that had little support outside its small membership ranks, in a short period of time became a major political force in the United States that created change around the world. ... Growing support for GLBT rights today can be traced directly to those participants in the Stonewall uprising who challenged power and authority and demanded respect and rights. The many people inspired by Stonewall who then became involved in the GLBT movement directly changed the horrible conditions and status of gay and lesbians, replacing fear with pride." He has expressed pride at having been among those who called for the first anniversary march, and has been heavily involved in collecting and preserving artifacts of gay history.

It was supposed to be the night Yvonne Ritter celebrated her 18th birthday as she headed to Stonewall the night of June 27, 1969. She lied to her parents about where she would be and put on a dress she borrowed from her mother's closet. Once the police raid started, Ritter was put in a police van with some of the other patrons, but when the door opened to put more people in, Ritter and others jumped out and ran. Ritter, who had been assigned male at birth but identified as female, although not to her parents, was afraid they would find out where she had been, but they didn't, and the following week she graduated from high school without incident. As an adult, Ritter completed her gender transition and became a nurse, doing much work with HIV patients. "I feel that a lot of those with HIV and AIDS may not have been given as good care if we hadn't gone through a change as far as it goes with our attitudes with gay and straight people," she told the blog Sang Bleu in 2014. "I think the people who were at Stonewall that night had great impact on really putting people in better perspective." She has also volunteered at the New York LGBT Center as a peer counselor for transgender individuals. In the same interview, she recalled the major role played by trans people at Stonewall: "These queens were the ones who were kicking it up. Actually at the front of the bar [they] were screaming 'We are the Stonewall girls, we wear our hair in curls, we wear our dungarees above our knobbly knees.' Truth be told the trans community were the loudest there."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes