There's a new trailer out for the movie Stonewall, which tells a story about the 1969 riots in which queer people pushed back against police harassment, and if your Facebook page is like mine, it's awash in friends arguing about just how hard we should boycott the film.

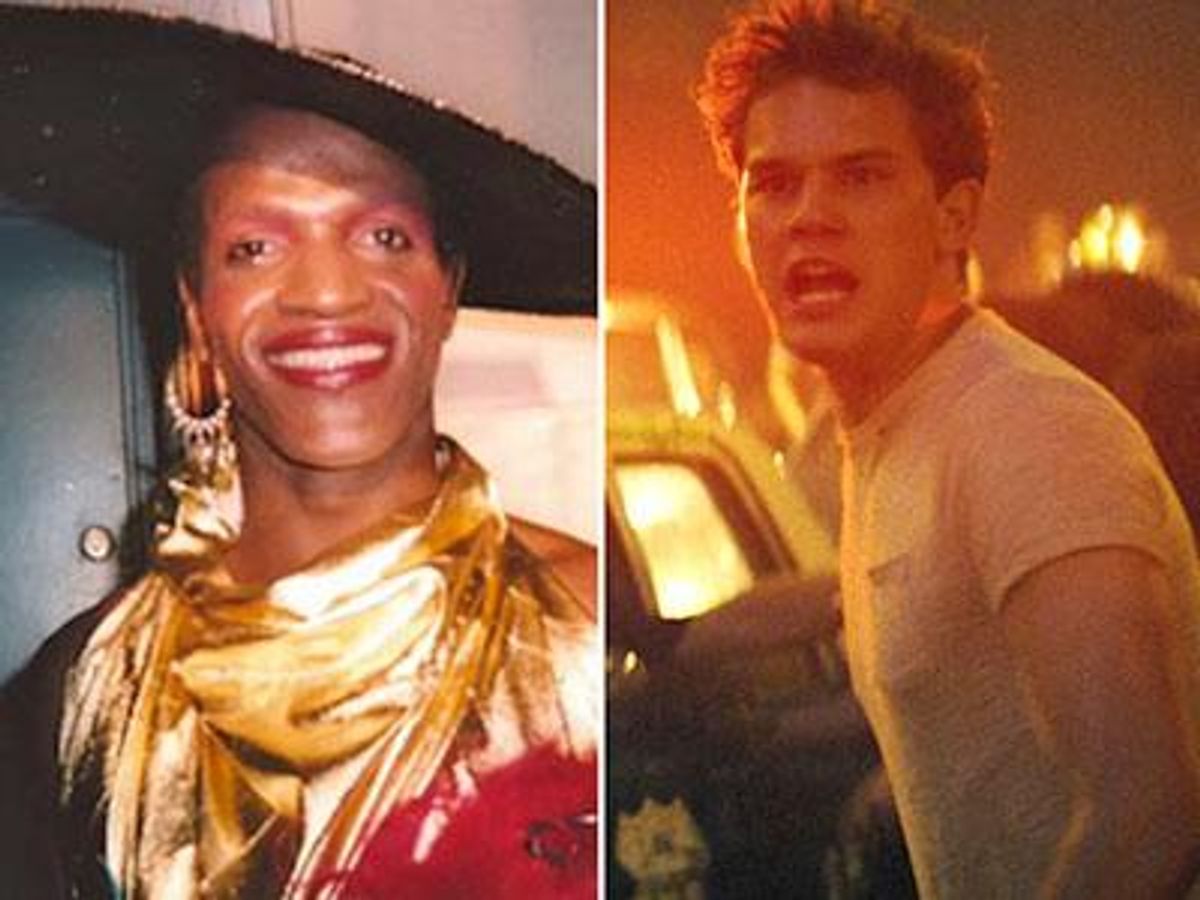

Here's the problem that a lot of people have noted: The trailer focuses on a cis white boy who moved to New York just in time to spark the riots. And that's hardly the full story of Stonewall, since participants included people of color, trans people, drag queens, and lesbians. In fact, I think it's the diversity of the riots that makes them as powerful as they were and still are.

Of course, this is just an ad for a movie, and we don't know how historically accurate Stonewall will actually be. Movies get history wrong all the time -- this is supposed to be entertainment, not a history book. Personally, I'm going to need to see the movie before I pass judgment on it (although I'm not exactly thrilled by the prospect of going to a film directed by the man responsible for the '90s Godzilla reboot).

But with everyone talking about Stonewall right now, it's a perfect opportunity to remember who was there and why they fought back.

Stonewall occupies an important place for queer people. When I was a closeted high school student in the mid-'90s, I wasn't brave enough yet to come out, so I did the next best thing: I volunteered for a history class presentation about the riots. It was only supposed to be 10 minutes long, but as I wrapped up my talk, I glanced at my watch and saw that I'd gotten so excited about LGBT liberation that I wound up talking about it for 45 minutes. After that display, coming out wasn't exactly necessary.

Greenwich Village was the place for queer New Yorkers to be in the 1960s. It's where much of the culture was emanating, and it was one of the safest places in the country to be out. I spoke to playwright Robert Patrick about what it was like back then, and he told me, "I hit New York and literally in my first hour in Manhattan, I wandered into the Caffe Cino, which was a bastion of experimental art, intellectual discovery, and homosexual revels. There was never a better time to be young than in New York in the 1960s."

But police raids on gay bars were near-constant. Remember, almost everything queer people did was illegal. You could be arrested for dressing in drag or serving a gay person a drink or touching another man or even just making eye contact for too long.

Early on June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn. The cops often left Stonewall alone, thanks to bribes from the mob owners. But this night, they swarmed the place and started arresting everyone. It was nothing too unusual, but for some reason, that night the crowd had enough. They started pushing back -- violently.

Accounts differ, so there's no way to know for sure who started things or who the ringleaders were, and there's no complete list of who was there. But participants included Marsha P. Johnson, a trans woman who's said to have smashed a police car. There was Storme DeLarverie, a butch lesbian who's said to have thrown the first punch. And many participants describe seeing Sylvia Rivera, a 17-year old nonbinary-gender drag queen who went on to be a leader for disenfranchised groups for decades.

And yes, there were white cis men there too. In fact, that's probably who most of the participants were. When I was 15 and studying the riots for my history class presentation, I was amazed to see photos of the patrons of the bar -- they looked like the kind of people I had a chance of growing up to be. But more importantly, I saw for the first time that people like me had fought alongside amazing people who didn't look like anyone that I, in my Connecticut suburb, had ever met. That's one of the reasons, I think, that Stonewall still resonates with us today; no matter your race or gender or expression, there was someone at the riot whose life was remarkably similar to your own. And all those different people were fighting together.

Why did they fight? In part because they just wanted to be left alone. These were marginalized people who were sick of being pushed around. The police wouldn't even give them the right gather in peace without being arrested, and finally that night they just snapped.

A story has it that the death of Judy Garland, a week earlier, triggered the riot. That seems a little too convenient to be true -- and as important a figure as she was, it's hard to imagine anyone getting so worked up about Judy that they ripped up parking meters and charged at police. But it's a bit of texture in what was one of the country's most chaotic years.

One thing they were almost certainly not fighting for: inclusion. Stonewall and the movement in general at that point were about rejecting the system, fighting back. It wasn't about fitting in. It was about being left alone and having the freedom to explore something outside of heterosexual society.

Although the trailer gives the impression that there's a line to be drawn from Stonewall to marriage equality, I can say with confidence that just the opposite was true. I've written extensively about the personal lives of the people affected by the marriage fight, both for my book Defining Marriage and for my podcast of the same name. In that work, I've uncovered a lot of hidden stories and previously unpublicized battles. But everyone I've spoken to about the 1970s has said emphatically that virtually nobody was thinking about marriage back then.

I spoke to Emily Rosenberg, an activist who was involved in lesbian and feminist groups in the 1970s. She told me, "The people I knew were getting out of marriage. Nobody had the least interest in marriage. ... It was unattractive. We'd all seen marriage and we all rejected it. ... We were a lot more radical than folks are today. We wanted to shake up the system, but we didn't want to be part of the system."

So is this movie harmful? Hard to say, but I think it offers a mix of optimism and whitewashing. It's great that people are talking about Stonewall. It gave me a lot of hope back when I didn't see a place for myself in the world. It also opened my eyes to just how diverse the queer community can be. And it showed me how strong we are when we stand together.

The movie comes out in September, and we'll know then just how accurate it is. But we don't need to wait until then to share the truth about the riots and hopefully bring hope to people just as the story did for me.

Stonewall wasn't the only time that queers rose up to demand the freedom to exist. It wasn't even the first time -- there were earlier riots in Los Angeles and San Francisco. But it was the one that got attention, and it marked the moment when Americans began noticing that queers exist, that we didn't want to hide, and that if we were abused, we were going to fight back.

I recently spoke to Cleve Jones about queer liberation. He's a longtime activist, was a friend of Harvey Milk, and is the creator of the AIDS quilt. He told me that he always says to activists, "You must demand everything immediately! Because only when enough of you demand everything immediately is there any hope of getting anything eventually."

Let's keep pushing for better depictions of the Stonewall riots. Hopefully, by demanding that the conversation include everyone immediately, we'll see fully inclusive stories eventually.

UPDATE:Director Roland Emmerich responds:

"I understand that following the release of our trailer there have been initial concerns about how this character's involvement is portrayed, but when this film -- which is truly a labor of love for me -- finally comes to theaters, audiences will see that it deeply honors the real-life activists who were there -- including Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Ray Castro -- and all the brave people who sparked the civil rights movement which continues to this day. We are all the same in our struggle for acceptance."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered