At the premiere of Starz's new drama Vida, it feels like the opening of a new city. Politicians issue proclamations at L.A. Live, designating the May 1 date as official Vida Day. There are cheers, nuanced speeches on the place of Latinx people, of women of color, of women who love other women.

That evening, there are few women as beloved as Tanya Saracho, the showrunner of the new series. A playwright turned executive producer, she's a Mexican-born queer woman, and in many ways the first of her kind. Her introduction at the premiere is met with a standing ovation and a few tearful eyes.

Perhaps the emotional response is to how, under her leadership, Vida has become a rogue, inclusive world of its own.

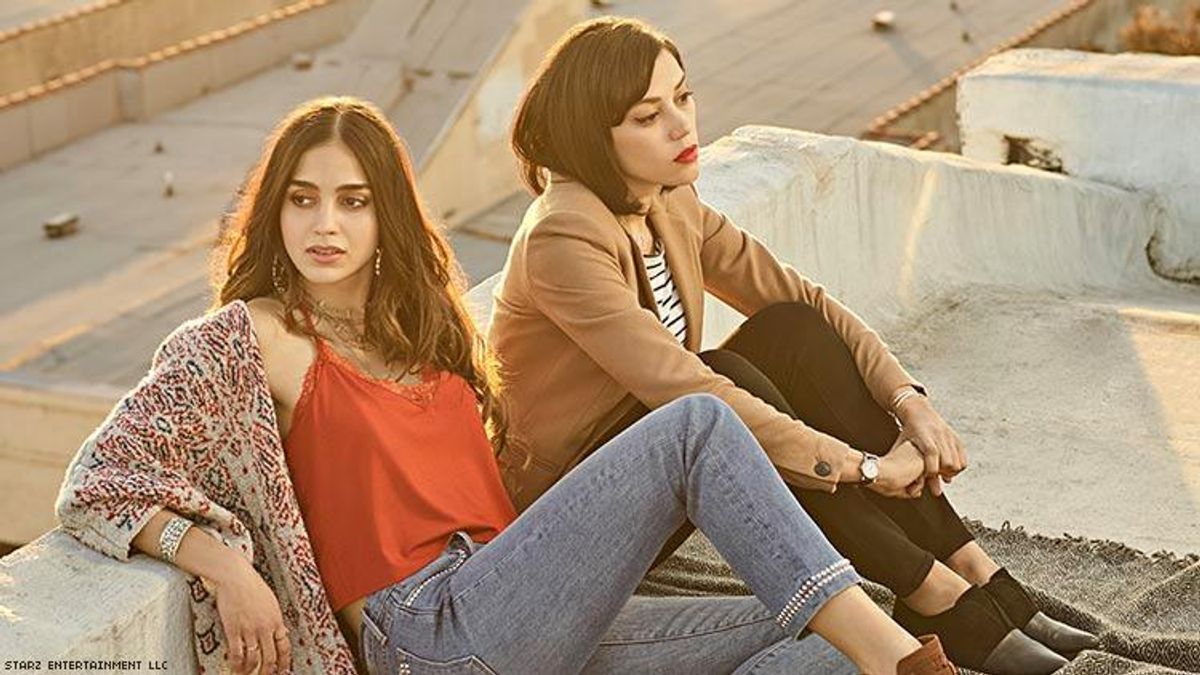

"This is a Latinx gaze show. This is a brown gaze show. The way we've been suffering through the white gaze for however many decades, sometimes the depictions of our people have not been fully realized," Saracho tells The Advocate. Her show, which explores the relationships of Latinx women in Los Angeles, particularly two sisters who come to claim the estate of their mother, Vida, and find a third of it has been left to her wife of two years, who they've never heard about. Faced with loss, gentrification, and the quiet violence of secrets, they try to make sense of the messes their Vida left behind, including their own lives.

"You're going to have very limited depictions, not fully fleshed-out depictions of the dominant culture, because it's not about the dominant culture," Saracho explains.

Although the show may feel niche, it's already making national headlines. It won the Episodic Audience Award at South by Southwest, outcompeting This Is Us, Tracy Morgan's The Last O.G., and Bill Hader's Barry. But the story of the writers' room has drawn nearly as much attention as the ones it's producing.

"My writers' room is all Latinx, and I'm very committed to all of them becoming showrunners, or running shows," Saracho announces with pride. "I know people seek me out to be their mentor, and I've chosen a few people I'm really invested in and nurturing their career and their aesthetic and just their person."

The entertainment industry has become increasingly about who you know and built for people who are born into relationships in the predominantly white agency and management world. Yes, you can further your career by working as an assistant and building bonds from the bottom up, but only if you can afford to live on minimum wage, which is industry standard. This has created an ecosystem where young creatives with well-connected, wealthy parents are the only ones who can break into the Hollywood machine. Not exactly ideal for Latinx storytellers, who face institutionalized discrimination from the start.

Yet Saracho has become a champion of her people, regardless of whether they have an agent, followers, or connections. "There's a woman named Nancy C. Mejia that I found from NALIP: The National Association of Latino Independent Producers; they gave me 13 scripts," she says. "They didn't have representation or anything like that, and I stashed one of the scripts, no agent, no phone number, I had to find her on Facebook, but I Googled her, and I was like, 'And she's a filmmaker? That's amazing!'"

Mejia is now represented by United Talent Agency, one of the most prestigious firms in Hollywood. "She is someone I guess I've really taken under my wing," Saracho says. "I don't want to sound patronizing, but like, she's so fantastic, she's also going to direct an episode next season, and she's in my writers' room. She's really important to me, and I helped her get an agent."

But for Saracho, changing one person's life is not nearly enough. "I get a lot of emails of scripts and pilots, and they want me to give feedback, and sometimes I can't because it's so many," she says. "And there's guilt in that, because it's like, ah! I'm trying to do my best to like, get us all into the castle called Hollywood, to keep the door open. But I try to do it in other ways too, because mentorship isn't just taking one person and following through."

For her, that's turning her script coordinator Jennifer Castillo into a staff writer. The reason? Merit alone. "She's been just amazing. I really like this symbiotic relationship we've developed." Meanwhile, Saracho is helping women on set, who rarely get the opportunities given to men. Female directors of photography are a rare breed; they make up only 2 percent of the working cinematographers in the industry.

"My cinematographer, she's an Afro-Latina who's amazing, from Colombia, an immigrant. She had never run a camera, a unit. She'd only been a second unit in Marcos, but she was never gonna get a first shot until somebody gave it to her, you know?" Saracho understands that opportunity goes hand-in-hand with being a guiding, forgiving force. "It's not just giving the first shot, because there's a lot of mistakes that happen and such, but it's also sitting with her and being like, 'OK, yes, that didn't go that well but don't worry, we're here for you' -- mentorship happens like that too."

When many marginalized people encounter executives who only leave space for a token, Saracho gets it, perhaps because she's had her own champions. "Marta Fernandez, who is my covering executive at Starz, it really matters that her name is Fernandez, you know? She gave me my first shot, so mentorship works in lots of ways, you know?"

But the new world order Saracho is creating is visible on-screen. She's previously worked on HBO's Girls, and with Vida, she offers the same acclaimed relationships between complicated women (plus raw, realistic sex), but these women are brown. They're queer. They're struggling with money, community, and culture.

They're also winning hearts.

"The media has embraced the terminology really well, like 'Latinx,'" Saracho says. "We have a nonbinary actor and we refer to them as they/them, and I love that they're using the term queer too. We obviously have that brown female queer gaze, which has not often been seen in the media. It's very specifically female, very specifically brown, very specifically Latinx."

Yet Vida offers immense nuance, particularly because vulnerable communities can be homophobic too. Vida was isolated and impoverished for being queer. The traditional culture that is so celebrated at points is the villain.

"I don't want this show to feel like it's a reaction to a traditional culture, because we do come from a traditional culture, and we ignore a lot of it for the first five episodes, then when you see the last episode, you see, 'Oh, wait, they're still in a patriarchal traditional culture where queer people can come under attack,'" Saracho explains. "We don't forget about it, especially because, we talk so much about how La Chinita is a safe space for queer women, but we remind ourselves that when we go out into the neighborhood, it's not so all the time."

For now, Tanya Saracho will keep building safe spaces of her own.

Vida premieres Sunday on Starz. Watch a trailer below.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered