television

How Mister Rogers Saved François Clemmons's Life

Francois Clemmons opens up about his abusive childhood, Stonewall, and staying in the closet for Fred Rogers.

May 05 2020 2:17 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Francois Clemmons opens up about his abusive childhood, Stonewall, and staying in the closet for Fred Rogers.

This interview was conducted as part of the podcast, LGBTQ&A.

Francois Clemmons was getting his MFA at Carnegie Mellon when he first met Joanne Rogers. They were both members of the Third Presbyterian Church Choir in Pittsburgh and Joanne brought her husband, Fred Rogers, to hear Clemmons sing a few of his favorite spirituals -- "Were You There," "There Is a Balm in Gilead," "He Never Said a Mumblin' Word" -- for Good Friday in 1968. Fred Rogers was taken with Clemmons and his voice, and soon after invited him to be a part of his TV show, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.

The singular mission of Francois Clemmons' life was to be a professional singer. From 1968 to 1993 when he appeared as Officer Clemmons on what would go on to become one of the most influential shows in television history, this fact never changed. Throughout the filming of the show, he sang at the Lincoln Center with the Metropolitan Opera Studio, won a Grammy Award for a recording of "Porgy and Bess," and in 1986, he founded and directed the Harlem Spiritual Ensemble, a popular group that toured the world.

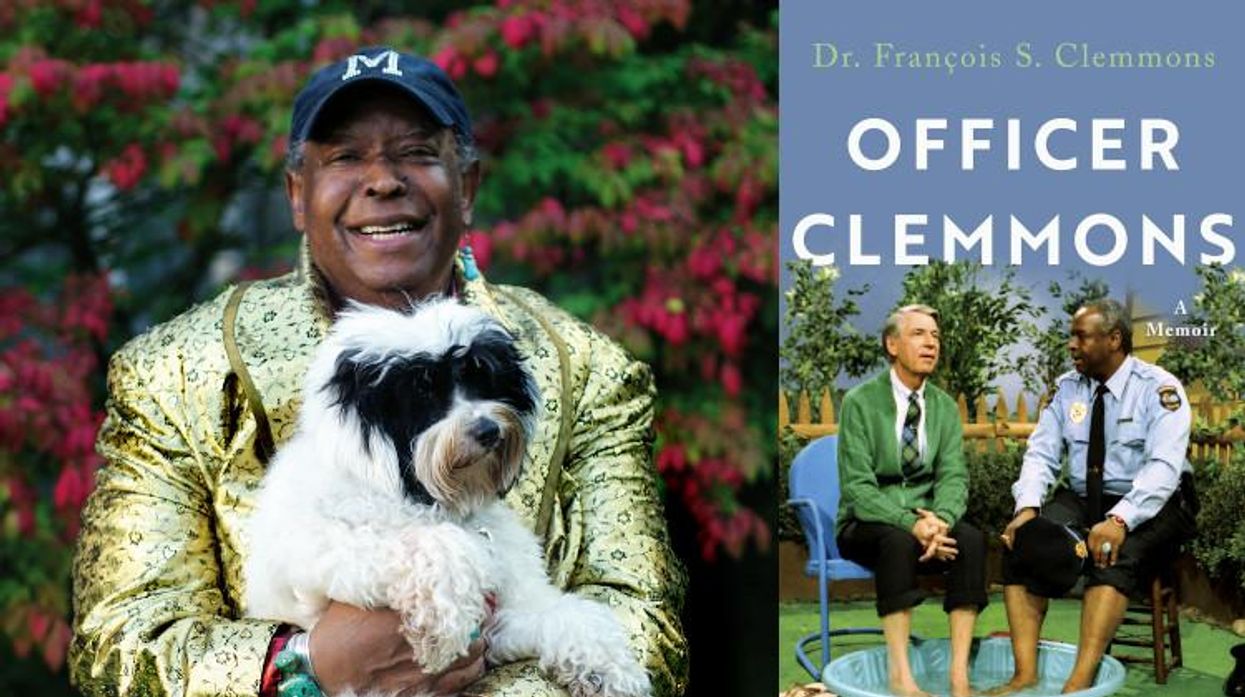

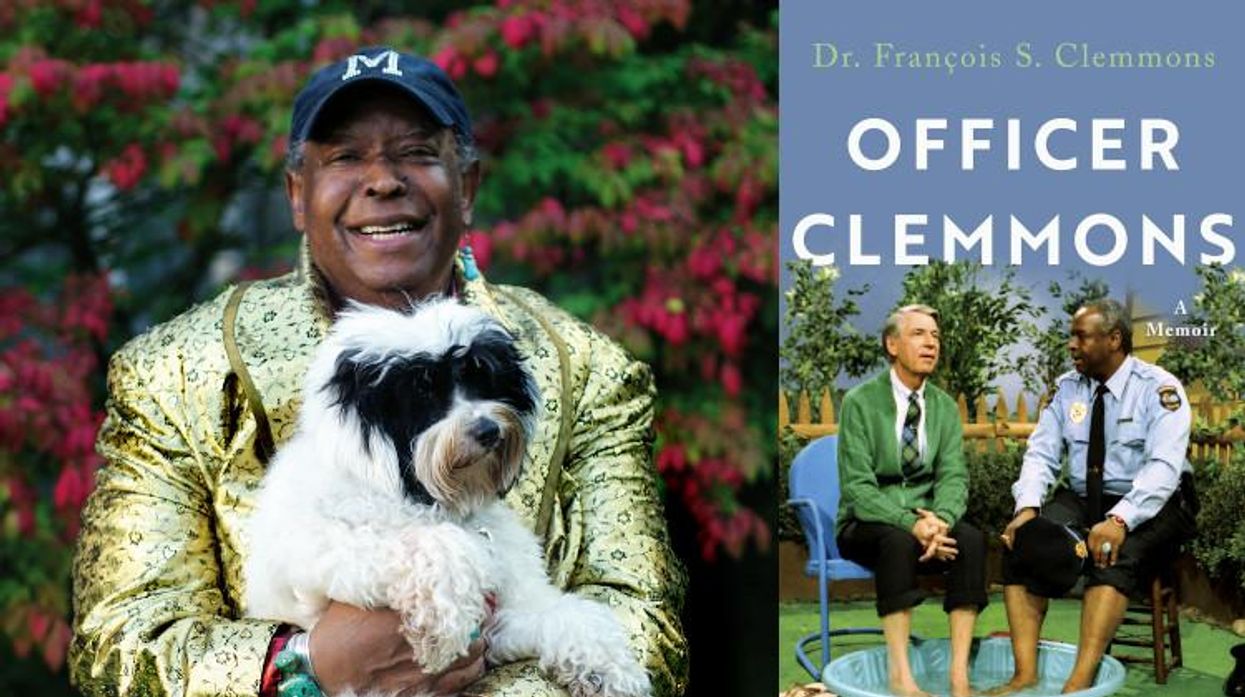

To celebrate the release of his new memoir, Officer Clemmons, I spoke with Clemmons on the LGBTQ&A podcast about his music career, overcoming a childhood of abuse, the Stonewall uprising, and making the "emotional, spiritual decision" to remain in the closet at the request of Fred Rogers.

Read highlights below and click here to listen to the full podcast interview.

The Advocate: A lot's been written about Mr. Rogers telling you that you couldn't be open about your sexuality if you wanted to be on the show. How did that affect how you presented and lived in your private life?

Francois Clemmons: Yes. I did give him my word that I wouldn't come out. He felt it would bring dishonor to the program because people disapproved, unfairly, but nevertheless they disapproved of openly gay people.

I felt an obligation not to be caught in compromising situations. There are places I wouldn't go and things that I couldn't do. The first time, someone told him I had gone to a club down in Pittsburgh called the Play Pen. I went there with a buddy of mine. We were dancing and sweating. And I went home. That was the extent of it. Evidently somebody took it upon themselves to tell him that I was seen there. I felt violated. I felt, "I'm an adult man. Who in the world is telling him what I'm doing? What I do when I'm not on the show is my business."

That was my first concern, that they were trying to control me.

Yet, you ultimately agreed to stay in the closet.

That was an emotional, spiritual decision. I began to feel that I was there for a reason, not just a happenstance...understanding that I had made an appointment with destiny, I thought about what would it be like if I didn't hold up my end of the bargain, if you don't sacrifice in a way that brings honor to the program, to you, to him, and to all black people, all brown people, all young people, and all gay people.

I really had this inner-sense of obligation and commitment and responsibility. Those words, they haunted me, because I couldn't be wild and crazy.

When you say "responsibility," who or what was that to?

The responsibility was to have a good face for white people who are watching the show. Black people were a little different in how they felt about my being on that show. White people would say, "That's terrible! Mr. Rogers was so kind to you. You are a gay person and if you were caught in an alley or the back of the truck somewhere, that's a disgrace." That's what I felt I could not allow to happen.

Were there any famous out gay black people at that time?

There weren't a lot out, no. You know who led the band? David Bowie. People like that were sexually fluid. They were open and honest about it. It was no mystery, and there were others. You're asking me specifically about black people though.

Because I wondered if you ever considered coming out and being one of the first.

I am a frontrunner. I've been blessed with strength and I will take care of myself. I didn't care what they thought, but I loved a man who did. Fred Rogers. It would have been very, very painful for him to have to go through that whole episode.

I hadn't had love from a father. It was so unconditional, so bountiful, that I said, "I can't give that up. I've never had it. Now I've got it, and I'm not going to throw it away. I'm not going to treat it lightly and casually. I love this man. He's treating me in a way that makes me feel whole, makes me feel like a person, that I'm wanted and needed and cherished." They became my family, all of them. Mr. McFeely was like a brother. Lady Aberlin was my big sister. Johnny Costa, the one at the piano, he adored me. He always took care of me vocally.

When Fred Rogers asked you to stay in the closet, he also suggested you get married. Would you have gotten married to your ex-wife had he not said to?

Yes, because he wasn't the only one who was advising me. I thought about it many times. She was my best friend, so we hung out all the time. All the time! An hour on the telephone was nothing for us. If there was a big dance or an act like The Temptations or Motown, coming to town, she would say, "I'll meet you there."

How did your gay friends react to you getting married?

They were surprised. They said, "What are you getting married for?" I said, "That's my destiny. Perhaps I can make this work. I do have a lot of affection for her. Maybe that'll turn into erotic attraction."

It never did. When I was making love to her, I was thinking about my boyfriend or somebody. It became apparent to me that I had made a serious mistake. I just couldn't make it work. I felt like a failure. That's what I had to say to myself: "You have made a mistake, but that doesn't deserve for you to be hung or killed. Hold your head up. Always apply yourself."

Did Fred Rogers ever meet any of the men you had relationships with?

Later on, later he did. I have to tell you, he didn't have anything against gay people. I didn't have very many relationships with people. I've never lived with anyone except my former wife. I've always lived alone. Not by choice. I think there were only two people that I had very quiet, demure relationships with. They lasted for 15 years each.

Were they quiet because you felt that you couldn't come out of the closet?

Yes. I began to understand that there were times when I didn't want that kind of public attention because it took away from the intimacy of a person I cared for a great deal.

When did you come out publicly?

Maybe about '88, '90. When I started The Harlem Spiritual Ensemble, I felt very strong. I was holding a big bundle of life. I decided, "I'm paying for myself. This is my group. I'm an adult. I'm not going to do anything to hurt anybody, but I'm coming out. I don't care who knows it. I'm not going to hide it."

From then on, if people asked, not very many, I told them yes.

What is it about black spirituals that made them your favorite style to sing?

First of all, I had been brutalized as a kid, so I carried a certain sad wound. The consolation was when I would sing, "Sometimes I feel like a motherless child." I meant that. "I feel like a motherless child. Sometimes I feel like a motherless child, a long way from home, a long way from home."

Something happens when I go there. I didn't know it then, but I know it now. I have access to the ancestors and I'm a different person. Fred said it to me, "Francois, I heard you sing at that concert. You're a very, very different person when you come off stage. When you're on stage, something else is going on. You have this almost effervescent personality, almost bubbly."

I'm not a bubble, but I have fun. When I put on my robes and my scepter and my crown, I'm a different person, and I know it. I didn't try to fight it anymore.

The way you talk about Fred, it seems like simply calling him a friend is not a big enough word to describe your relationship.

There are people who put a little nuance in there and say it was sexual. It was not sexual at all. It was spiritual. It was emotional. He supported me in a way that I had never had.

I came from the wrong side of the tracks. I was trying to struggle to get my way through grad school and thought I was going to sink. He came along. He offered me a job and I began to think, "He's telling the truth. I can trust this man." I let my guard down. I accepted the generous offer that had been given to me.

It wasn't just one way. I found myself sharing with him certain, very, very heavy experiences that I had had, that he didn't understand. He would say, "Francois, what does it feel like to go to bed hungry?" It's very difficult to put something like that into words. We talked about what it felt like to be beaten by your parents. He would say, "You had a very difficult life, Francois. Why aren't you acting wild and crazy and angry?"

I said to him, very honestly, "You're a part of it. You're one of the reasons I don't act crazy and go off the handle, but I am wounded and I know it." What I found is I carry that reservoir. Sometimes I open it up and I peak at it, but it doesn't control me anymore. When I go out to sing a spiritual, I dredge up the pain.

You moved to New York City in 1969, the year Stonewall took place. What did you remember hearing about it?

Lord have mercy! I moved in August. It had just happened a month or two before. I snuck down to the Village. I didn't tell my wife where I was going, or anybody. They had swept and cleaned it. It was almost pristine. You couldn't tell where the violence had gone on, but the spirit of that violence was down there.

I wasn't the only one. There were tourists who had come down to look and see this little club, this little nowhere, nobody, Stonewall club, and say, "This is where they were fighting the police, the gay people?" Sometimes you can tell that there were other gay people there. We started a casual conversation. "Where are you from? Why'd you come down here?" We all had come for the same reason.

I wanted to see if I could get a taste of gay life in America. They talked to me very freely, very warmly. I took courage and asked them some questions and stuff about it.

Even then, it was recognized as a massive deal.

It was a massive deal. I have to tell you. I was a boy who didn't want to be Officer Clemmons because the police were very brutal. They shot black boys in the back. They strung them up. Everybody was against you. I knew about police brutality. I couldn't imagine them fighting those policemen. I have so much, so much respect and admiration because they decided they had had enough.

I wasn't that old, but I've lived to see gay people standing up, standing tall, and saying, "You can not push me anymore. I've been pushed enough." I saw a change. Because of the Christian indoctrination that I received, I never imagined that gay people were going to stand up for themselves like that.

Francois Clemmons' memoir, Officer Clemmons, is avaible now.

You can listen to the full recording of our interview with Francois Clemmons on the LGBTQ&A podcast.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes