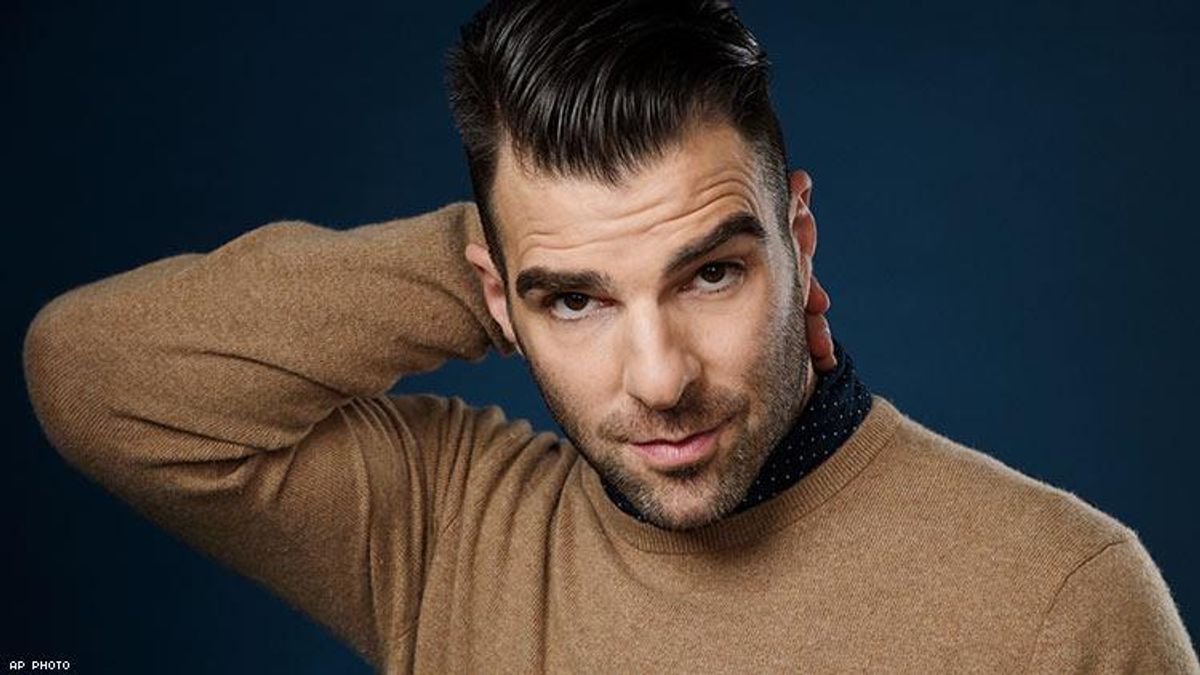

After helping make TV and film franchises like Heroes and Star Trek successful, out actor Zachary Quinto is stepping into a more down-to-earth role -- as an "ugly, pockmarked, Jew fairy" in the revival of Mart Crowley's 1968 play (and 1970 film), The Boys in the Band. In the Ryan Murphy-produced Broadway staging, Quinto portrays Harold, the cutting character whose birthday sets the Boys' drunken hysteria into motion. As Quinto prepped for the May 31 opening, he spoke with The Advocate about his political passions and why Boys touches such a nerve with queer men.

The Advocate: Hi, Zach. Tell us about your history with The Boys in the Band. Have you seen the film?

Quinto: No, I've actually never seen it.

What was your awareness of it when you heard about the revival?

I knew of its legacy. But I didn't have a very informed opinion of the play until I did our initial reading of it and had subsequent conversations with Joe Mantello, Ryan Murphy, and David Stone about the production of it. I feel like I have a much deeper, fuller understanding of the play now, and towards its resonance and power. It was sort of stigmatized when the movie came out. I feel like I was under the influence of some of that stigmatic thinking. So it's been really nice to get to know it with fresh eyes and from the experience of being inside of it, which is quite fun.

One of the themes of the play and movie is how gay men interact with each other. How do you think that's evolved in the 50 years since the play premiered?

Well, the play takes place in a time when the only place when gay men could be open and authentic with themselves was in private. There wasn't the freedom that we enjoy today, and I think that's probably the most significant evolution in the past 50 years, is the ways in which we as an LGBTQ community have become more integrated and more authentically ourselves.

But at the same time, there are still hallmarks of these archetypes within the LGBTQ community and in particular, the community of gay men, that's interesting to revisit through the prism of 2018. The evolution is people still say some of the things that are in the play -- "Oh, Mary!" and "Queen." [It's interesting] to view the evolution of the vernacular and the colloquial mode of communication, which I think in some ways evolved from a need to release a certain kind of pressure. I think some of that exists, it's just that it's more mainstream than it was 50 years ago.

The play does get ribbed for how cruel the characters were to each other. Did that feel off?

Look, we're working on it right now and we have a lot of conversations in rehearsal: "Wow, how are these people friends?" "Why would you be friends with anyone who speaks to you like that?" But you have to take into consideration, and what I think the play is really exploring, is this projection of self-loathing. These characters exist in a society which belittles them, berates them, attacks them, arrests them, persecutes them to a degree that reinforces such depths of self-loathing that I think we have evolved beyond. There's still a lot of backwards thinking and a lot of bigotry against LGBTQ people in this country -- without question -- especially under the auspices of the current administration.

But I do feel like we've moved beyond the place where the LGBTQ community is at the mercy of how they are perceived by mainstream, heteronormative society. So I think that's one way in which a contemporary revival of Boys in the Band can show audiences how far we've come. One of the ending theses of the play is that if we can only learn to not hate ourselves so much [we'd be happier]. In his despair and drunken stupor at the end of the night, what Michael is left with is this desire to not hate ourselves so much and then maybe we wouldn't be so brutal with one another. And I do think that's evolved. Though there are certainly undercurrents of catty shadiness. We throw shade. It's kind of a hallmark of the community. There is a kind of wit and repartee in which certain kinds of gay men still relish. That's part of what makes the community so colorful and dynamic in certain ways. But I also feel the characters in this play relish it as well; I just think it goes too far and it gets fueled by booze and drugs and all the extenuating circumstances in Michael's apartment.

Tell us about Harold. He comes across as one of the most in-control and self-aware of the characters.

I think that's true. Harold is incredibly self-aware, incredibly observant. He exists in his own kind of bubble of time and experience, and I think part of that is because he's in touch with his own self-loathing. His first line in the play, "I'm a 32-year-old, ugly, pockmarked, Jew fairy." He doesn't pull any punches with anyone, least of all himself. He knows himself well; he knows his shortcomings. He's aware of his strengths and his weaknesses. Michael is the closest match to him in this room of men, but I think he knows his ability to overpower anything that's thrown at him and he does it with an air of detachment and enjoyment that he derives from people trying to get a rise out of each other and him.

I got the sense that characters like Harold and Emory feel a certain sense of pity for the tortured protagonist Michael. Did you get that?

I think the character of Michael lacks a compass. He doesn't have a strong sense of self and he generates a sense of self by looking outside of his experience, whether it's in his religious convictions and beliefs or in the way he relates to other people. He looks for a sense of purpose and definition outside of himself. He doesn't generate it from within; I think the other characters know that. I don't think Harold has a particularly high tolerance for that; he expects more from his friends. He wants Michael to step up and step into himself, and part of that unleashing at the end from Harold to Michael is saying, "This is what you are, and if you stop trying to be something else, maybe you'll find some measure of peace."

The thing is, ultimately, is that these guys are all in it together. They're all up against the litany of social adversity that was just a hallmark of the early- to mid-1960s America and still exists in some vestige today. That's where the camaraderie comes from; they can eviscerate each other, they can call each other out, they can talk down to each other and say horrible things, but at the end of the day they're there for each other, they understand what each other is going through, and they've got each other's backs. That's the beauty of the play; it's the beauty of Harold saying to Michael, "I'll call you tomorrow" and mean it. Earlier in the play he says, "You're going to be a mess tomorrow, you're going to be embarrassed, you're being vicious." They know each other well enough to anticipate that. And I don't think any of it is worth any of them not being there for each other, and that's really the beauty and power of the play -- showing up for your brothers and being there for them in their moments of grace and moments of indignity, and understanding in a different world, maybe 50 years from now, we won't have to endure these same kinds of attacks and diminishments that fuel this kind of bitterness. And luckily, by and large, we can say that's true. We can't say that's true entirely or unqualified.

I noticed all the men share a common worldview that they're low on the totem pole of society. I thought that may be what also brings together; they're all very observant.

Yes, but none more than Harold!

Speaking of Harold, he wears sunglasses throughout the play, ostensibly because he's stoned. Are you going to wear sunglasses in the play?

I have some great glasses that I found and some rose-colored lenses put in. I'm really enjoying the opulence of the character. David Zinn, who's the incredible set and costume designer for the play, has hooked up a really great outfit. We're leaning into the characterization and having a good time doing it. Harold calls himself ugly; he doesn't think he's beautiful, but he knows how to put himself together and he leans into that. We're creating a character physically for Harold, which includes certain aesthetic choices; sunglasses is one thing, I don't have curly hair, so a curly hairpiece and a great outfit.

And pockmarks constructed via makeup.

Don't you know it, honey. We're going the full nine yards.

All the actors in this production are gay. How is it working in this environment and what does it bring to the table?

It's one of things that drew me into the production and ultimately made me want to do it, other than the fact that I'm really good friends with most of all of the cast members. I've known Matt Bomer for over 20 years -- we went to college together -- I've done a play with Brian Hutchison, I've done a movie with Charlie Carver, I've known Jim [Parsons] and Andrew [Rannells] socially for years. So there was a real sense of connection among all of us before, but the idea that this is an entirely openly gay cast, all of us successful in our own right, working and creating unique opportunities for ourselves. I think there's something remarkable about that -- gay director, gay producer, gay creative team. It's something that's very declarative in that kind of Ryan Murphy assertion of our collective power; there's something about that that sets this production apart and makes it even more resonant in this culture, where I do think that the fight for equality certainly includes the notion of gay actors being able to play straight characters, just the way straight actors are often cast in gay roles.

The idea of standing up and leaning into our authentic selves and identities and saying this is who we are unapologetically, we're going to celebrate that, not because it's the only thing we can do, but rather it's the thing that sets us apart and our talents range wide and our ambitions range wide and this is a declarative step towards pursuing many different types of opportunities. But every now and then in that pursuit we have to remind ourselves, and in many cases, the world at large, who we are and what we have fought for ourselves and what we've benefited from as a result of the fights of other people who came before us; many, many people who came before us and on who's shoulders we stand. This is a great moment, 50 years later, to say look where we are and look at who we are. Let's celebrate the work we've done and the work we're doing and the work we've yet to do.

Speaking of progress, do you have hope we'll be rid of this administration soon?

Here's the deal. In one way or another, we're stuck with one version or another of this administration until the next presidential election in 2020. What happens in November of this year is going to be a real bellwether for where we're headed.

I was just recently involved in the campaign of Conor Lamb, who won in a predominantly Republican district in Pennsylvania, in my hometown. He upset a congressional Republican opponent who existed in a place where Trump won by many points.

I believe the balance will shift. If we're talking about all these investigations and the undeniable corruption of this president and administration, I would love nothing more for them to be accountable for their egregious misrepresentation and attacks on equality of all kinds, not just in the LGBTQ community, but across the spectrum of disadvantaged, disenfranchised, impoverished people all over the country. These are people who have no one's interests at the center of their Machiavellian ambitions. I'd love to see them brought to some measure of justice. I have to be reminded, though, in the eight years when Obama was president, eight years where all us liberals and social progressives relished in the progress made, there was a whole swath of the country who felt exactly how we feel now. It is part of the political spectrum and political process.

The thing that concerns me more and possibly most is how divided we are. It feels like the 24-hour news cycle, social media, technology, and the infiltration of all lives by these devices that we carry around created echo chambers that don't allow for the kind of public discourse and respect that used to be the cornerstones of our democracy. So we follow who we want to follow, we hear what we want to hear. It's dwindled the lanes of thought down to a two-way highway; you're either going one way or another.

That's what concerns me most; the lack of interest in connecting with each other and hearing each other and respecting each other even if our points of view or beliefs don't line up. I have to think and believe and hope our country that we can do infinitely better than this sham of a president who's currently in office, but I don't know. And I've talked to a lot of people in the political world who think he's going to get reelected. That not only would we have to deal with this for another two years, but another four after that. That thought makes my blood curdle, and I just hope that people see through these egregious lies and misguiding of our country.

I just have to say this is our democracy. We elected him; we have to deal with it. At this point, all we can hope to do as long as we have to put up with him is stem the bleeding. There's no progress we're going to make under him. There are no legislative advancements for the transgender community in the military and in schools, where they're discriminated [against] and bullied in so many parts of the country. And the environment. Anything that anybody can do to back a midterm election in their city and their state -- that should be our number one priority right now. And looking at the way in which Republicans have built themselves up from the state level of government all the way to Congress, we have to figure out how to combat that. I think the House is teetering; the news that Paul Ryan is retiring. Good riddance. We have to take advantage that the GOP is clearly seeing the writing on the wall.

The youth movement that's coming out of the tragedy at Marjory Stoneman and the way those young people have stood up and said we will be counted; maybe not today but the second we turn 18 and have the right to vote, we will be counted. That's the future and that's what we have to get behind. We have to amplify those voices and weather this endless storm. The instability of this White House is so disconcerting. I hope we pull ourselves together, and anyone remotely interested in the future of the country recognizes we all have to participate and show up and do our part.

What frightens is me is the precedents we're setting by allowing Trump and his Cabinet to keep doing what they're doing. On top of how Trump communicates, without an editor and without decorum. There's no policy, no consistency. It's just so unchecked and so uninformed. That's what worries me, the destabilization of the office of the presidency. This buffoon of an entitled, lucky, rich businessman turned reality star is just repellent. The idea that that's the standard that we've set for the presidency of the United States. Where do we go from here?

In 2020, what is the future of the Democratic Party? Who does have the political acumen? Put Oprah aside. That's absolutely the wrong direction for us to be going in. We need to be identifying the future of political minds, not celebrity minds. That conflation and the way that we've lost the idea that celebrity used to mean you're good at something; it doesn't mean that anymore. The idea that Oprah, as good as she is at what she does, could be president is misguided. That's not her skill set, that's not her training or her experience. She's great at interviewing presidents and connecting powerful people and doing good in the world, but she's not a political mind. And she even identified that herself.

The thing that scares me too is if he does resign, Mike Pence is no better. Especially for the LGBTQ community, he's the worst avaricious opponent of our community that we could ever hope for. So it's not like what's waiting in the wings is a rainbow flag and a hug for our agenda. He creeps me out more than anyone in the administration. The lady doth protest too much. I feel like we just need to weather the storm and get through what we're in, whether it's in six months because he gets exposed for the fraud that he is or two years because hopefully America wises up and realizes we can do infinitely better. Then we get back to the real work, which is moving agendas forward that will help equalize the playing field for all different kinds of people in the country, which is the cornerstone of why the country was founded in the first place.