Theater

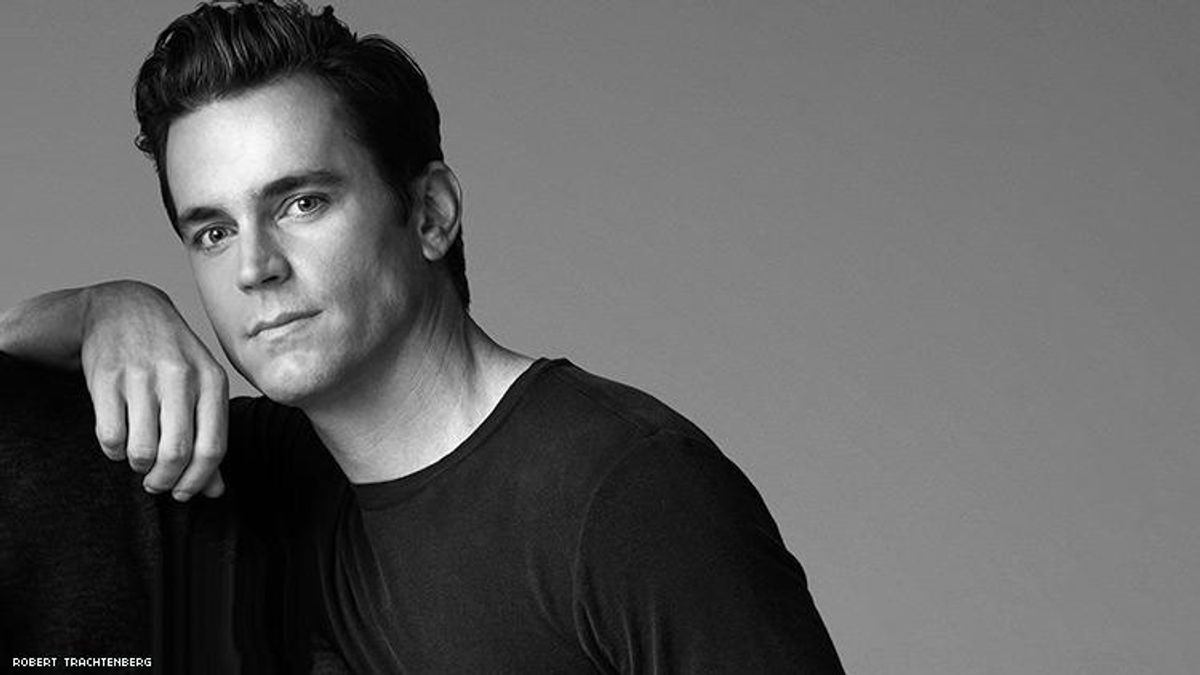

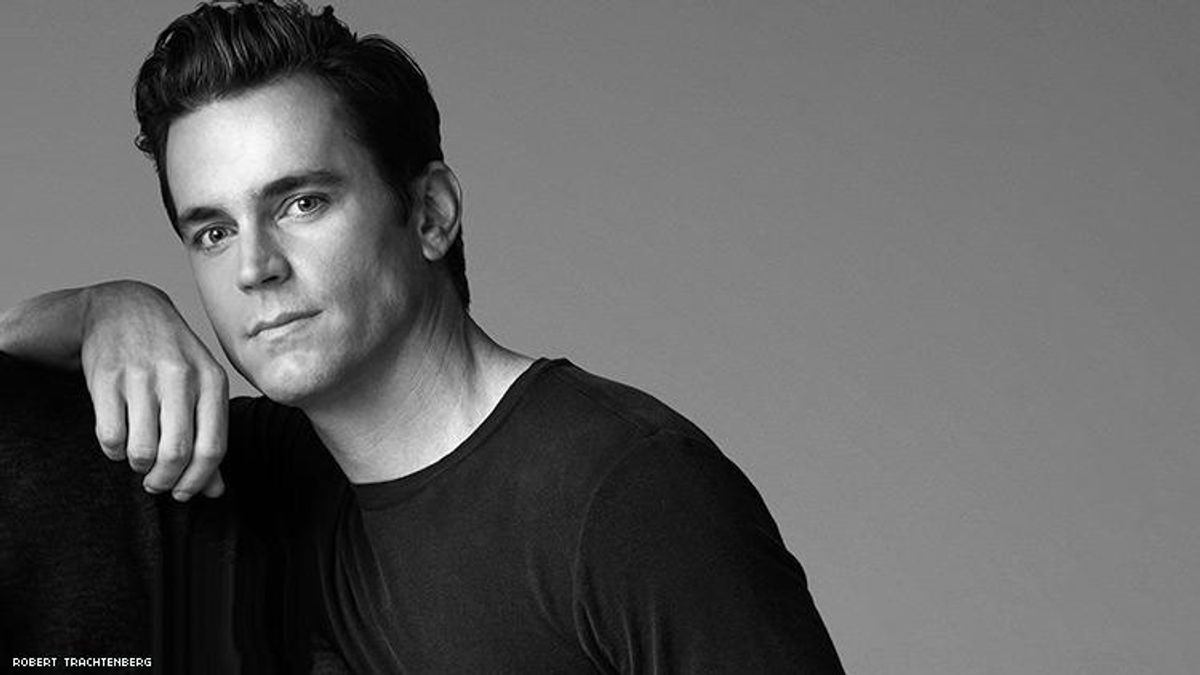

Matt Bomer Is Tired of the Mean Gays

The out actor discussed his role of Donald in The Boys in the Band, which showcases a stubborn mean streak in gay culture.

May 21 2018 1:52 PM EST

May 21 2018 3:07 PM EST

dnlreynolds

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The out actor discussed his role of Donald in The Boys in the Band, which showcases a stubborn mean streak in gay culture.

In The Boys in the Band -- the Broadway revival of the 1968 play about a gay party that flies off the rails -- Matt Bomer portrays Donald, the best friend of the event's host, Michael. Donald is grappling with his identity through analysis and also retreat -- he fled New York City in order to distance himself from gay culture. But the party forces him to once again confront it as well as himself.

In the following Q&A, Bomer discusses the role and the lessons that can be learned from Boys, including perspective on how far LGBT people have advanced in the past few decades, plus a stubborn mean streak that exists among certain queer men. Bomer also notes how learning about the original cast gave him new appreciation for his own career as an out actor.

And don't miss The Advocate's full cover story with the play's entire ensemble cast of out actors -- Bomer, Zachary Quinto, Jim Parsons, Andrew Rannells, Charlie Carver, Michael Benjamin Washington, Tuc Watkins, Robin de Jesus, and Brian Hutchison.

The Advocate: This is your first Broadway show, right?

Matt Bomer: Yeah. I've been cast in a few, but I always had to leave to do other jobs or for some sundry reason that I shouldn't have left -- and never under dramatic circumstances or anything, only because I needed a paycheck. But yeah, this is really my first Broadway show.

Why is Boys in the Band something that you wanted to be a part of?

You know, it's interesting. When they first reached out to me about it, and I read the first act, I thought, Oof. Man. What's this all about? And then I read the second act, and I said, "Oh, OK. I get it." And I am interested in specific parts of our history. So much of my understanding of our culture started with ACT UP and Larry Kramer and then Angels in America. I was so unaware of pre-Stonewall life and all that that entailed. And it's actually really hard to do in-depth research on it because so much of it is lost. It was either hidden in the shadows or in apartments like where this birthday party is taking place. We lost a lot of that generation to the AIDS epidemic.

Including a lot of the actors of that show.

Yeah. Exactly, exactly. That time period was really interesting to me, and the more research I did about that time period the more I understood why these men were behaving the way they were. I also, just in my experience -- I'm 40 now -- but in my experience, coming of age as a gay man, I've definitely seen echoes and a resonance of these relationships and how these people were dealing with each other and themselves in my interactions with people.

The play debuted 50 years ago. What do you think is still true about gay relationships that hasn't changed since then?

Oh, I don't know. I think so much has changed exponentially, especially in the past five years. It's just been so progressive in so many ways. So I don't know that I look at it as something of "Oh, what hasn't changed?" To me, it really is a period piece.

It's a retrospective to look back on. This is how people were behaving with each other when society was telling them that who they were was fundamentally wrong. When their analyst was telling them that they had a psychological condition that was tantamount to bestiality -- comparable to bestiality, the way we think of that now. And when they couldn't go out in public and even be seen dancing together. There was really this law where men who were gathered together had to have at least one woman with them and they had to be dancing three feet apart. There were real stakes to these situations for them in their lives. So everywhere they turned, they were being met with "Who you are is wrong and unacceptable." And then so those arrows start to go inward towards themselves and then be projected out to their closest relationships.

Then for you, perhaps, a modern viewer would see this and think, Wow, look how far we've come?

I would hope so. It's so hard to be -- and it's gonna be a really seductive thing once there is an audience there, because I think they're gonna be interested in coming and seeing people serve tea to each other at this dinner at this birthday party.

Oh, there's tea served.

There is tea to be served! There is. But there's also a real pathos beneath that. And that's what we have to try to stay true to, you know? But it is going to be this dialogue once there is an audience there. I can't say what they're gonna find from the piece. All I can do is try to play it as truthfully as possible and not get seduced by just making it a Golden Girls episode.

I can't tell [audience members] what to think of it. My hope is that they would look at it and go, "Oh, my gosh. We can never repress human beings and whoever their true nature is as long as it's not criminal and hurting anybody else. Because when we do, these are the repercussions."

Had you seen the play before reading the script?

I actually hadn't. I remember when I was a freshman in high school, I read Torch Song Trilogy and then I got into Larry Kramer and Tony Kushner and people like that. As I mentioned, my history sort of began with those pieces. I just never had gone all the way back to Boys in the Band, and it was my loss. After we did the first reading, I watched the movie and had subsequently spoke with [the film's director] Billy Friedkin, who's wonderful. Really found so much to love in the film.

What did you love about it?

I loved that in 1970 ... people, especially people like Billy Friedkin, who is a straight man, had the courage and the fortitude to make this movie with the original cast and not take all the stars the studio was trying to throw in, but to take these men who had originated these roles and make a movie out of it -- an unapologetic movie. I think it was really ahead of its time. And to be honest with you, it's all I really have from that time period to look back on. I mean, I didn't read back-ordered issues of After Dark magazine and look at photographic essays of New York at the time, but that's really what we had to go off of.

It was a miracle that it was made.

I appreciate the courage of all those artists at that time. Making the choice to be a part of that movie had real stakes to it. You look back on their careers, and I don't think it killed any of their careers. I really don't. But the courage it to do it at that time, to put it all out there at that time, is really inspiring.

You're an out actor. Did watching the film and learning about the lives of its gay actors give you any new perspective or appreciation of what you've accomplished in your own career?

A lot of those actors went on to work and do great things. I mean, Leonard Frey was nominated for an Oscar later on. Unfortunately, we had this horrific epidemic that swept through our people. I think that's what, sadly, brought an end to things. So kinda look back and saw, "Wow! These guys were 10 times more courageous than someone has to be now." Yeah. Absolutely I can appreciate that.

Can you talk about your character and what you think Donald says about gay life?

Donald is a really interesting role to approach because so much of the play, he's standing on the sidelines and observing. And he is this loyal friend who, come hell or high water, he's gonna be there at the end of the night -- the last man standing by his best friend's side. I think he's someone who's really trying to find a way to live. He's in analysis. He's sequestered himself off to the Hamptons to try to get himself out of the city, away from the constant temptation. He's someone who's really stuck and perceives himself as a failure, not only because of his identity as a gay man, but also because of just who his parents are inherently.

At this party, in the one of the week where he where allows himself to let it all hang out, and he's watching all these things go down. He's seeing his best friend come unglued. He's seeing a relationship that's fraught with a lot of drama. He's seeing a man who may be straight, may be gay, really struggle with his sexuality. He's someone who's really flamboyant. And he's just watching it all go down and trying to figure out, "How do I live as a gay man at this time? How do I find a way to live that I can be happy with? That I can wake up and face every day with without hating myself?"

How do you think a modern-day audience member might respond to that dilemma?

I hope they would respond to it in the context of a period piece. I think there are really amazing and healthy ways to live your life as a gay man now. We don't have those same types of stigmas attached to it. It's not illegal. We can dance in public. Lord knows. Therapists no longer consider it a psychiatric condition. ... So I would hope they can look back on it in the context of 1968. It's like that great quote from Angels in America: "The world is always spinning forward." And this was a time when it hadn't spun forward quite enough. It's the turmoil that ultimately led to the outward expression of rebellion that was Stonewall. It's all underneath this piece. It could no longer be contained in an apartment. It was starting to explode and manifest itself outwardly.

Do you think that gay men being mean to each other is still part of our culture?

Fuck yes. I mean, as I'm sitting and watching these scenes between Harold and Michael where they're just trying to outdo each other in terms of just reading each other, and how they're receiving the read from the other person and trying to top that one? I've seen that go down at parties. I've seen inherent cruelty. I've seen humor disguised as cruelty. I don't think it has the same stakes now than it did then. I feel like when society is telling you all these things and everyone around you is telling you all these things, in a weird way, you need to hear them from the people you love because it somehow confirms all the things you're starting to feel inside yourself. But, yeah, certainly, those are the echoes I'm speaking about.

I'm not saying that all gay people are nasty, or all gay people are mean. But it is something that I've seen in specific groups of people or from specific individuals who either haven't done the work on themselves or who find their identity in being the person who can read everyone in the room or use it as a defense mechanism. Those things are still alive and kicking today.

Why do we need to see this play today?

We need to see this today to look back on where we were as a culture in 1968. And I'm not saying every gay person in 1968 was like this. This is a very specific group of men locked and trapped in this apartment together right before Stonewall when this underlying turmoil was reaching its fever pitch, its boiling point. Where people didn't want to have to hide in the shadows anymore, but they didn't know how to not. And so I hope we can look back on it and see not only how far we've come, but how repression, societal, interpersonal repression manifests itself in ways that were damaging to these men. And hopefully look to the now and to the future and remember that quote from Angels, that the world is always spinning forward, and how can we continue to move forward today?

Beautiful. And finally, if you had to play the telephone game at a party, I'm curious as to who you would call.

Oh, shit. I think I would probably pull a Donald in that one and opt out of that game. There's nothing really to be gleaned from that phone call. There's nothing good that's gonna come from that conversation. I think it's probably mutually understood and mutually, let's bury that hatchet.

Well, thank you so much, Matt. We're so excited to see you in this role.

Hey, listen. It's an ensemble piece. I'm blown away by the artistry of all these guys. And I get to sit back in many parts of the play and just watch them do their thing and marvel at it, so I hope you enjoy it.

The Boys in the Band opens May 31 on Broadway. Get tickets here.