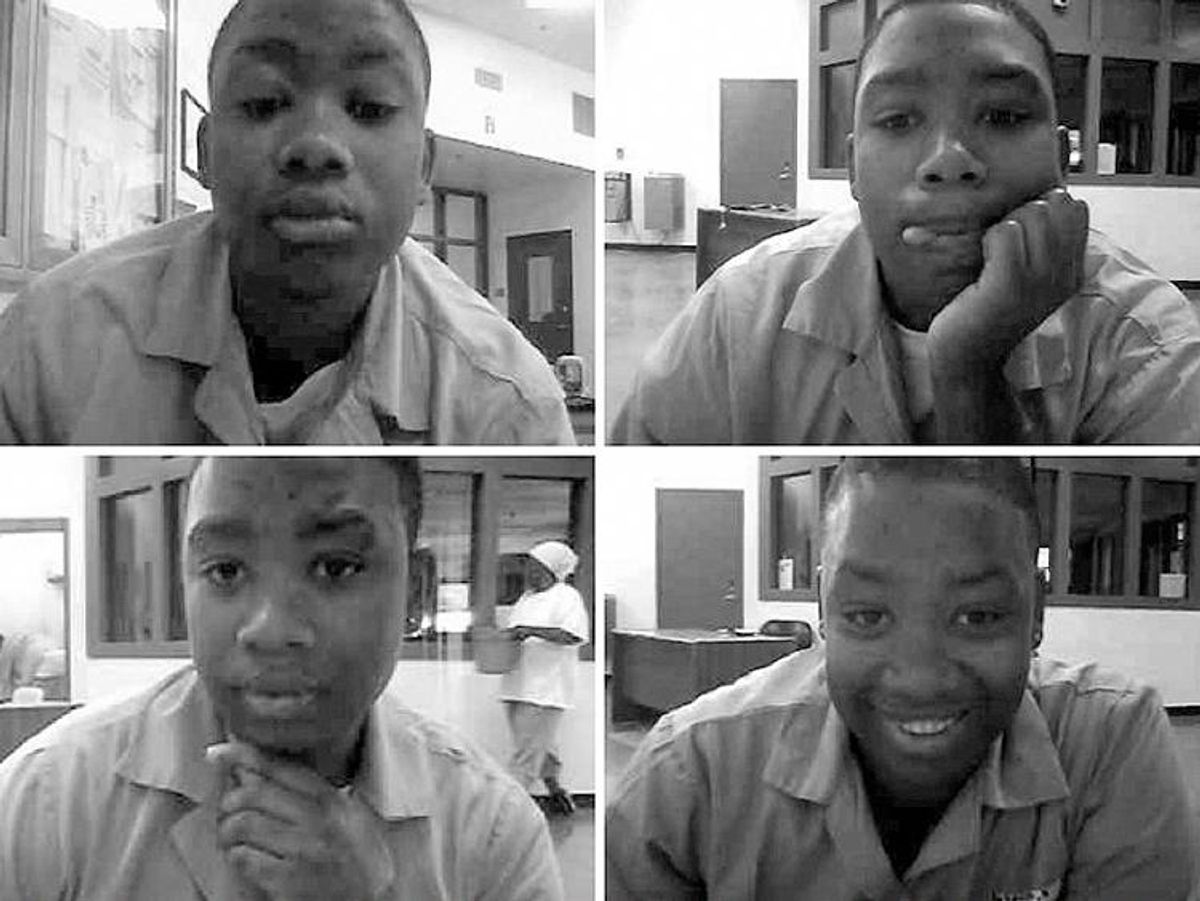

After nearly five years jailed with women, Ky Peterson is now one step closer to being recognized as the man he is -- even while he remains incarcerated in Pulaski State Prison in Hawkinsville, Ga.

Peterson -- the black trans man at the center of a groundbreaking case involving violence, gender identity, and the dysfunctional prison system -- recieved his first dose of hormone therapy on February 26, the 25-year-old tells The Advocate.

"This has been a long hard journey, and now I can see the difference between speaking up, rather than staying silent and never getting anything done," Peterson says via email. "But I had great people encouraging me to never give up along the way."

Three days after this report's initial publication, Peterson recieved his first injection of testosterone, or "T," as it's known colloquially. In an email he sent to his girlfriend on Friday after his first shot, Peterson said he was feeling "pretty good so far."

He is among the first transgender inmates to receive transition-related care while incarcerated in Georgia, after the Department of Corrections updated its policy last April following a federal lawsuit filed by black trans woman Ashley Diamond. (Diamond settled her suit for an undisclosed amount earlier this month.)

A spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Corrections declined to discuss details of Peterson's specific treatment, but did confirm that "a transgender man receiving testosterone therapy would remain housed in a female facility."

Asked whether transgender inmates receiving hormone therapy would be placed in administrative segregation, also known as solitary confinement, where trans prisoners are often held allegedly "for their own safety," the spokeswoman hedged.

"Offenders who are receiving hormone therapy may be housed in general population if that assignment is appropriate based upon their security, educational, training, behavioral, mental health, and other needs as assessed by the GDC," writes Gwendolyn Hogan in an email to The Advocate. "Placement in administrative segregation or another specialized living unit is based upon the same considerations."

Peterson is serving a 20-year-sentence for "involuntary manslaughter" after killing the stranger who was raping him in 2011 in an abandoned trailer in the rural Georgia mobile home park where Peterson lived with his two younger brothers and his mother.

Although Peterson contends the single, fatal shot he fired at his attacker was in self-defense, the young man was advised to take a plea deal that sentenced him to 20 years in prison. The Advocate's reporting uncovered a crucial error in that sentencing, prompting even the district attorney's office that prosecuted Peterson to admit his sentence was "not proper." Since that revelation, Peterson has remained incarcerated and has allegedly been subjected to hostile treatment at the hands of Pulaski State Prison officials. After Peterson was placed in "protective custody," also known as solitary confinement, he attempted to take his own life last June.

That same month, Peterson's girlfriend, Pinky Shear, had compiled a dense packet of information about the importance of gender-affirming medical treatment for transgender people, after Peterson's repeated pleas for access to hormone therapy went unanswered. Shear says she sent identical copies of these informational packets to Pulaski State Prison warden Angela Grant, deputy warden of care and treatment Aimee Green, chief counselor Brad Metz, and former Pulaski medical director Dr. Yvon Nazaire, who was dismissed earlier this year after the Georgia Bureau of Investigations launched a series of inquiries into the deaths of at least nine female inmates at Pulaski under Nazaire's care. Shear also sent a copy to Peterson, in hopes that he could deliver the information to care providers directly.

The packets Shear created (a copy of which The Advocate obtained) featured a complete copy of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health's Standards of Care, which affirm that hormone therapy is an appropriate course of treatment for individuals suffering from gender dysphoria, the clinical diagnosis which describes a severe disconnect between one's internal sense of gender identity and their gender as assigned at birth.

The packets also included a letter from a licensed clinical social worker in Atlanta who had assessed Peterson through a video-conference appointment, affirming that Peterson met the criteria for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria according to the latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

"It is this clinician's opinion that [Peterson's] pursuit of hormone therapy and surgical interventions will greatly improve his quality of life," wrote the therapist. "By further integrating his affirmed gender identity into his core self, [Peterson's] self-esteem, confidence, and relationship with others will improve."

Legal and advocacy groups including the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Transgender Law Center also provided resources for the packet about federal guidelines for treating transgender inmates as well as the risks faced when trans individuals are housed in facilities that do not correspond with their gender identity, or are denied medically necessary health care related to their transition.

Finally, Shear composed a letter on Peterson's behalf, citing her existing power of attorney over Peterson's medical, financial, and legal matters while he is incarcerated, formally requesting that Peterson be given access to hormone therapy.

"Given the current social/political climate in regards to transgender issues, you are in the very unique position of taking a proactive position when it comes to the care and treatment of Pulaski's transgender population," Shear wrote in her letter to Grant. "While Ky is the 1st inmate to request hormones and care, he is not the only inmate who suffers from Gender dysphoria. ... I know for a fact that at one point, there were no less than 15 gender nonconforming and male identifying inmates just in dorm E8."

Shear pointed to the Georgia Department of Corrections' newly enacted standard operating procedure for meeting health care needs of transgender inmates, which took effect April 15 of last year. The new guidelines arose from Diamond's federal lawsuit filed last February, alleging that Georgia DOC staffers failed to protect her from repeated rapes while she was incarcerated with men for three years. The lawsuit also alleged that GDOC officials refused her the hormone therapy she'd been on for more than a decade when she became incarcerated for a nonviolent burglary charge.

Georgia's new guidelines for treating transgender prisoners were announced less than a week after the U.S. Department of Justice weighed in on Diamond's case, contending that denying medically necessary care to transgender inmates was unconstitutional.

As a result, the GDOC's current standard operating procedure determines that transgender inmates "will receive thorough medical and mental health evaluations from appropriately licensed and qualified medical and mental health professionals." If these clinicians agree that an inmate has gender dysphoria, the GDOC will then develop a "treatment plan ... that promotes the physical and mental health of the patient," according to the Department's Standard Operating Procedure document, policy number 507.04.68.

The updated policy also repeals the GDOC's long-standing "freeze frame" approach to granting inmates transition-related care, doing away with the stipulation that inmates were only eligible to receive the same treatment they had maintained prior to incarceration. For a young, low-income trans-masculine person like Peterson, obtaining hormone therapy or other clinical interventions was not feasible when Peterson was incarcerated at age 20. Nevertheless, Peterson had long identified as male, and had been living according to his authentic male gender identity since childhood.

As the procedural wheels began turning, Peterson received his first psychiatric consult regarding his request on July 27, 2015. In a letter sent to his girlfriend that same day, Peterson recounts being overcome by emotion when he heard his preferred name called by the doctor who was reviewing his request:

"I was waiting in the mental health office, when an older guy came out, looked at me and said 'Mister Peterson?' I looked around for a second trying to figure out who he was talking to, but I was the only one there. Then he said, 'You did request to be called Kyle Peterson? I don't think I read it wrong.' I stood up, shook his hand and said he was right."

Peterson went on to explain that the doctor acknowledged that he didn't have much experience working with transgender individuals, but said he had reviewed the informational package Shear composed for prison officials. The two men shared a smile as the doctor asked Peterson to "walk this walk together," closing his remarks by asking "Are you OK with that, Mr. Peterson?"

"Yeah, I'm a grown-ass man, and I'm not ashamed to admit that I was crying like a baby by the end of that meeting," Peterson writes. "There are no words to describe how good it felt for someone to respect me as a human being."

After another two psychiatric consults through the month of September, Peterson heard no news on the status of his request for treatment. But on January 22 -- just four days after Diamond had an arbitration meeting with GDOC officials about her lawsuit, wherein she reportedly mentioned Peterson -- Peterson was sent to the endocrinologist to determine the appropriate levels of testosterone he should be prescribed.

While Shear hesitates to directly connect Diamond's legal success and subsequent advocacy on Peterson's behalf to the encouraging development about Peterson's hormone therapy, she coyly suggests that very little happens by pure coincidence in Georgia.

Indeed, Diamond's attorney, Southern Poverty Law Center staff attorney Chinyere Ezie, tells The Advocate that SPLC's lawsuit on Diamond's behalf was integral in lifting Georgia's "freeze frame" policy regarding transgender health care. As a result, "many trans people in the Georgia prison system gained access to needed hormone therapy for the first time," she explains. "However, Georgia prisons remain a difficult place to be trans, so there is an ongoing need for advocacy work and monitoring to ensure that Georgia's promises come true."

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella