This interview was conducted as part of the interview podcast, LGBTQ&A.

"As queer people, one of the ways that we're oppressed is we're denied our history and formal education. It makes us feel like we're impossible and like we're unprecedented. And that's just not true," Alok Vaid-Menon says.

"We've actually been here for thousands of years and we've actually created incredible networks of resistance."

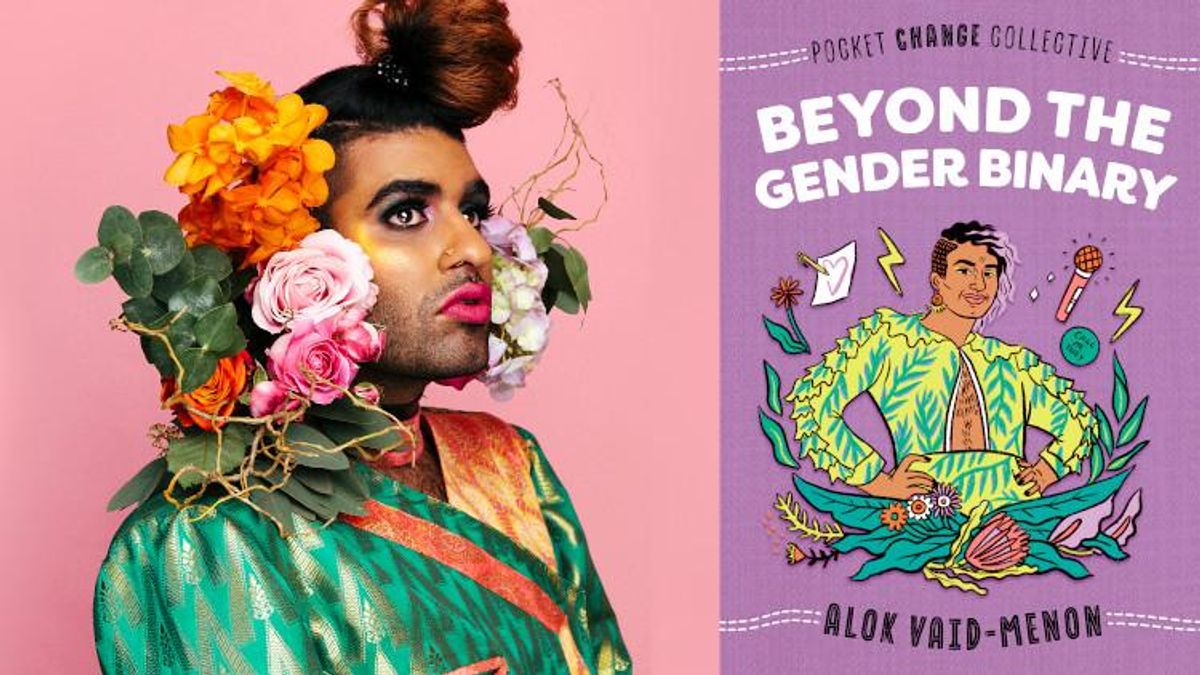

Vaid-Menon's life and work are contextualized amongst the long history of gender-nonconforming people in their new book, Beyond the Gender Binary. Though not included in history books, people living outside the binary have always existed. Beyond the Gender Binary challenges the world to be a kinder, safer place, and encourages anyone with questions about their gender to not shy away from them.

To celebrate the release of their book, Vaid-Menon spoke with the ">LGBTQ&A podcast about why denying LGBTQ+ people our history is so dangerous, the beauty of transition, and why they feel most joyous wearing a beard, full face of makeup, and a miniskirt.

Read highlights below and click here to listen to the full interview.

Jeffrey Masters: You write about asking writing groups, "What feminine part of yourself did you have to kill in order to survive in the world?" How do you answer that question?

Alok Vaid Menon: I believe it was in 2014, I hooked up with an ex-partner, which is always a bad idea. He was like, "You're just using they/them pronouns to be political, but you're not actually trans, right?" And I just remember feeling so deeply violated because what occurred to me is that the only ways that I had been loved required my disappearance and misrecognition.

I began to question if I was ever loved for me or if it was for my ability to fit into other people's fantasy of what I should be. Then that night, I was hanging out with friends and I sat them down and said, "I can't do this anymore. I need to present more feminine and I'm very afraid of what that's going to mean for me, but I've come to a point now where I can't sustain the psychological toll of this."

After that, it was a second becoming. I bought a lot of dresses and lipsticks. And I didn't really know what I was doing, but it felt so good. It felt like coming home.

JM: Early on, so much of the focus was on your femininity. I think it would be easy to assume that you were a trans woman. Are you able to describe what you were experiencing and how you knew it was something else?

AVM: I think for me for a long time, I questioned, is my femininity something that is organic or is it something that was imposed? Because when I was young, my father left for a job elsewhere, so I was mostly raised by my mom and my older sister. Traditionally male stereotypical roles were something I never really imbibed. I never really had that kind of socialization or indoctrination and, in many ways, I was treated as a woman.

When I was a little kid, I was wearing girls' clothes almost exclusively. And it was never actually about gender, it was just about, That's what Alok wants to wear. I began to ask, "What is organic?" Then I realized that's a false binary and a really misleading framework because I don't think it's possible to separate The Me from The Us. And I think that's both tragic and incredibly beautiful, that we are deeply enmeshed in culture and everything that surrounds us.

And so when I started to experiment with my femininity, I removed any idea of purity. I removed any idea of authenticity and instead I subscribed to joy. "Does this give me joy?" I thought about medical transition and then I was like, "Actually that wouldn't make me feel joyous."

I feel most joyous with a beard, a full face of makeup, lipstick, and a miniskirt. And that's just where I feel the most me. And I think that feelings for me as an artist are so much more poignant than words. And so it's less about "I'm trans" or "I'm a woman" and it's more about, "I feel good."

JM: When you were figuring all of that out, visibility was smaller for anyone outside the gender binary. Did it feel like you were going about it alone?

AVM: Yes, absolutely. And what was even more complicated is that I was one of the few visible gender-nonconforming people in the media at the time, and so I really had no precedent.

And then my coming into myself was also a public coming into itself. That is something that I'm only now on the other side of six years later, really starting to process how painful that was. It was like, "Am I ready to be taking the steps I'm taking or am I taking them because politically that's what the world needs?"

I found myself in incredibly dangerous situations because I would say things like, "Okay, I'm in New York City. I'm going to wear dresses every single day to say fuck you." But then I was literally getting attacked and I wasn't ready for that. No one prepared me, but I felt like I had to do that because there was no other visibility for someone like me.

JM: As a society, I think we have a lot of experience talking about sexuality. Conversations about gender have only reached a mainstream level recently.

AVM: Yeah, I think there's a historical reason for that. I keep on returning to history because I think as queer people, one of the ways that we're oppressed is we're denied our history and formal education. It makes us feel like we're impossible and like we're unprecedented and that's just not true because we've actually been here for thousands of years and we've actually created incredible networks of resistance.

JM: You said that growing up, you wearing dresses was just treated as who Alok is. When did you start to connect that to gender

AVM: It wasn't me making that connection with other people making that connection. The paradox of trans feminine life is that when we're young, people call us sissies and girls and f****ts and trannies and pussies. And then when we actually come into ourselves and say, "I am trans." Then they're like, "You're a man." And it's perverse.

I never understood what I was doing as gender or femininity. I just understood it as like joy and creativity and expression. And then people started to call me all these names. And people started to say that because I was so feminine, that meant I was gay. And if I was gay, that meant I should die. And so I began to police my voice, my gestures, how I walked, who I spoke to, my internal monologue. And that sense of a body becoming a closet is the psychological trauma of so many queer men that I know.

But the difference, I think, between a lot of transfeminine people and masculine cis gay men, is that so many of us actually took the time to sit and ask, "Am I only trying to do this masculine facade because of my fear of abandonment, my fear of violence? How much of me is mediated by fear?"

What I think is so beautiful about transition is so many of us know that we're going to experience more violence. That obnoxious narrative in the media that we're opportunistic and we're transitioning because we think that we're special or because we want nice recognition is so wrong because a lot of us transition knowing that we're going to be exposed to even more harm and vulnerability.

But the reason that we do it is because we want to fashion ourselves in ways that are not mediated by other people's fears or projections. In that way, I think it's one of the most joyous things I've done in my life, even though it's created so much precarity, because I fundamentally am living my life as a materialization of my own meaning and not other people's.

JM: You wrote that underneath people's discomfort and hatred of gender-nonconforming people is "a deep, deep pain." That strikes me as such a generous way of looking at people who've hurt you.

AVM: I'm sure you have these experiences as well when you're bullied in high school and then 10 years later your bullies message you on Facebook and say, "Oh, I was actually gay." And you're like, "Oh my God, of course."

And this is the secret truth that a lot of queer people don't want to name, which sometimes our most vicious bullies actually were within our own community because internalized self-hatred leads to some of the most lethal treatment of other people.

If you were really so secure and so confident in your gender, me looking like this would just be another way to live. But it's perceived as a threat because you don't have security in your own gender. And so actually, who is the person suffering here? Me or you? Because I know who I am and I have security, but a lot of this world doesn't. I began to realize in my own work, the real transformative gesture is to say, the reason you are hurting me is because you templated this first on yourself.

I think cis men are just continuing the anti-feminine violence that they've done to themselves onto me. My existence shows them that they didn't have to do that, that they didn't have to compromise their femininity in order to be masculine, that they could hold both, and instead of saying, teach me, they say, eliminate me.

JM: And masculinity is tied to power.

AVM: Psychologically, when people get access to power, they don't want to divest of that. This is the mythology of gay people assimilating into straight society: the acceptance was contingent on your eraser of difference.

I don't believe that we should have to disappear ourselves in order to be approved by other people. My conception of equality and liberation is that we should be able to look and act like we are without having to accommodate to some other people's norms.

JM: How has your experience of gender affected who you're attracted to, your sexuality?

AVM: I feel like for me, it's really difficult to disentangle the violence I experience from my sexuality. That's something I'm really trying to work on, and this year in particular because I've been violated so much on the basis of my gender. Sexuality feels dangerous.

I literally have had random strangers on the street come up to me and stick their hands in my pants and say, "How much?" And like that the implications of that on my body and the fear of knowing that so many trans people are murdered for being desired, it's just so painful. What people don't understand is that most anti-trans murders are domestic violence. Thereby intimate partners, right? That the people we love and the people that we have sex with can be the most lethal and violent to us is really hard for me to stomach.

I know that there are people who aren't going to be violent to me, but it's a fear that I have. And I feel like that fear is something I'm really trying to work through in my life, and it's a work in progress. I want to be someone that's totally self-accepting, blah, blah, blah. But I'm afraid.

And I think it's important to name how we're afraid because I think so many people just say, "I'm strong, I'm confident, I moved on. This is me." And I'm actually like, "No, I'm freaking terrified because I don't trust people because I have no reason to trust people because I've been violated so many times and misrecognized so many times in my life." But I'm trying to let my guards down, so we'll see how that goes.

JM: You write about feeling beautiful. Is feeling beautiful and feeling desired by another person the same thing for you?

AVM: That's something I've been thinking about a lot right now because I've started designing fashion design for the past three or four years. For my fourth collection, I'm trying to ask, "What does desirability look like for me?" And that has been the hardest creative project of my life because we inherit such a reductive idea of what desire is. I'm trying to unlearn that and say, "What is desirability look like for me?"

Because truth be told, I feel most desirable in the kind of aesthetics that people dismiss as most ugly. So it's really hurtful and I think a lot of gender-nonconforming people have spoken about this in the past, that we're complimented when we most approximate the binary.

I'm really struggling to separate my conceptions and my assertions of my beauty and my desire in a world that links beauty to binary. And that's why I started to design fashion because I really believe that images create new possibilities. People don't know how incredibly attractive and beautiful we are.

Beyond The Gender Binary by Alok Vaid-Menon is available now.

The full interview with Alok Vaid-Menon is available on all podcast platforms. LGBTQ&A is produced by The Advocate magazine, in partnership with GLAAD.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella