The Supreme Court has declared that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry the person they love, bringing marriage equality to all 50 states.

Justice Anthony Kennedy's sweeping, eloquent decision affirming the freedom to marry was joined in full by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor.

But the decision was not unanimous -- Chief Justice John Roberts authored the minority's dissent, while Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and, most vociferously, Antonin Scalia, writing additional dissenting opinions. It's unusual (though not unprecedented) for every dissenting justice to write separately, noted SCOTUSblog.

At the conclusion of his dissent, Chief Justice Roberts offers a backhanded word of congratulations:

"If you are among the many Americans -- of whatever sexual orientation -- who favor expanding same-sex marriage, by all means celebrate today's decision. Celebrate the achievement of a desired goal. Celebrate the opportunity for a new expression of commitment to a partner. Celebrate the availability of new benefits. But do not Celebrate the Constitution. It had nothing to do with it."

While dissents are not legally binding in the way a Supreme Court's ruling is, they do offer a window in the arguments that likely took place during the Justices' closed-door conference after they heard oral arguments in the case in April.

Read on to find the highlights and the overarching argument from each of the justices' dissents.

Chief Justice John Roberts: This issue should have been decided by the people, not the Court.

Chief Justice John Roberts: This issue should have been decided by the people, not the Court.

"[The plaintiffs] contend that same-sex couples should be allowed to affirm their love and commitment through marriage, just like opposite-sex couples. That position has undeniable appeal...

But this Court is not a legislature. Whether same-sex marriage is a good idea should be of no concern to us. Under the Constitution, judges have power to say what the law is, not what it should be. ...

"Although the policy arguments for extending marriage to same-sex couples may be compelling, the legal arguments for requiring such an extension are not. The fundamental right to marry does not include a right to make a State change its definition of marriage. ... In short, our Constitution does not enact any one theory of marriage. The people of a State are free to expand marriage to include same-sex couples, or to retain the historic definition. ...

Today, however, the Court takes the extraordinary step of ordering every State to license and recognize same-sex marriage. Many people will rejoice at this decision, and I begrudge none their celebration. But for those who believe in a government of laws, not of men, the majority's approach is deeply disheartening. ...

Five lawyers have closed the debate and enacted their own vision of marriage as a matter of constitutional law. Stealing this issue from the people will for many cast a cloud over same-sex marriage, making a dramatic social change that much more difficult to accept. ...

The majority's decision is an act of will, not legal judgment. The right it announces has no basis in the Constitution or this Court's precedent. ... Just who do we think we are? ...

This universal definition of marriage as the union of a man and a woman is no historical coincidence. Marriage did not come about as a result of a political movement, discovery, disease, war, religious doctrine, or any other moving force of world history -- and certainly not as a result of a prehistoric decision to exclude gays and lesbians. It arose in the nature of things to meet a vital need: ensuring that children are conceived by a mother and father committed to raising them in the stable conditions of a lifelong relationship. ...

The Constitution itself says nothing about marriage. ... The majority's driving themes are that marriage is desirable and petitioners desire it. ...

When the majority turns to the law, it relies primarily on precedents discussing the fundamental "right to marry." ... These cases do not hold, of course, that anyone who wants to get married has a constitutional right to do so. ... None of the laws at issue in those cases purported to change the core definition of marriage as the union of a man and a woman. ...

Neither petitioners nor the majority cites a single case or other legal source providing any basis for such a constitutional right. None exists, and that is enough to foreclose their claim. ...

Unlike criminal laws banning contraceptives and sodomy, the marriage laws at issue here involve no government intrusion. They create no crime and impose no punishment. Same-sex couples remain free to live together, to engage in intimate conduct, and to raise their families as they see fit. No one is 'condemned to live in loneliness' by the laws challenged in these cases -- no one. ...

One immediate question invited by the majority's position is whether States may retain the definition of marriage as a union of two people.

Although the majority randomly inserts the adjective 'two' in various places, it offers no reason at all why the two-person element of the core definition of marriage may be preserved while the man-woman element may not. ... If the majority is willing to take the big leap, it is hard to see how it can say no to the shorter one. ...

It is striking how much of the majority's reasoning would apply with equal force to the claim of a fundamental right to plural marriage. ...

I do not mean to equate marriage between same-sex couples with plural marriages in all respects. There may well be relevant differences that compel different legal analysis. But if there are, petitioners have not pointed to any. When asked about a plural marital union at oral argument, petitioners asserted that a State 'doesn't have such an institution.' But that is exactly the point: the States at issue here do not have an institution of same-sex marriage, either. ...

The Court today not only overlooks our country's entire history and tradition but actively repudiates it, preferring to live only in the heady days of the here and now. ...

By deciding this question under the Constitution, the Court removes it from the realm of democratic decision. There will be consequences to shutting down the political process on an issue of such profound public significance. Closing debate tends to close minds. People denied a voice are less likely to accept the ruling of a court on an issue that does not seem to be the sort of thing courts usually decide. ...

Indeed, however heartened the proponents of same-sex marriage might be on this day, it is worth acknowledging what they have lost, and lost forever: the opportunity to win the true acceptance that comes from persuading their fellow citizens of the justice of their cause. And they lose this just when the winds of change were freshening at their backs.

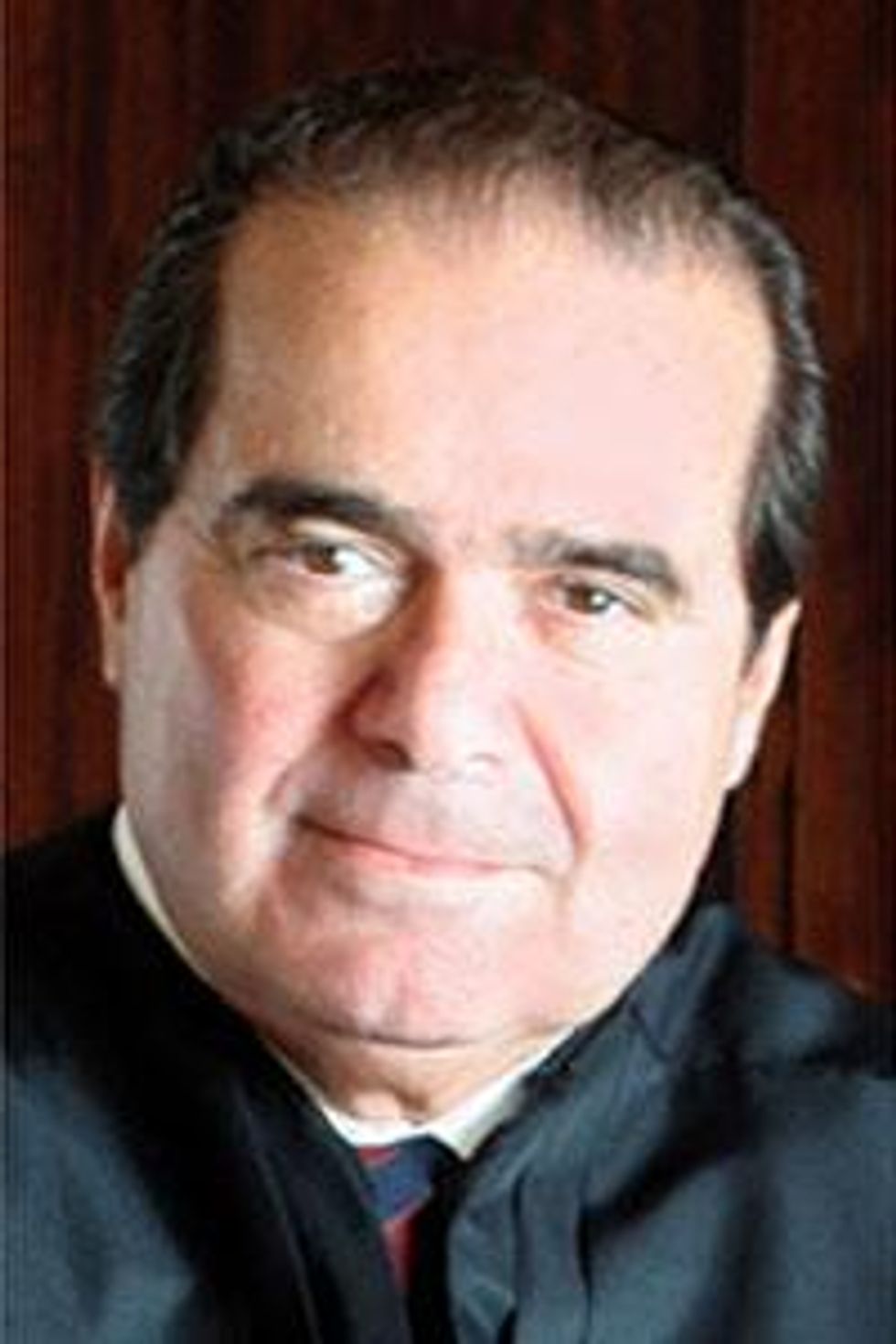

Justice Antonin Scalia: Today's decision is irresponsible, "impotent," and an affront to American democracy.

Justice Antonin Scalia: Today's decision is irresponsible, "impotent," and an affront to American democracy.

The substance of today's decree is not of immense personal importance to me. The law can recognize as marriage whatever sexual attachments and living arrangements it wishes, and can accord them favorable civil consequences, from tax treatment to rights of inheritance.... It is of overwhelming importance, however, who it is that rules me. Today's decree says that my Ruler, and the Ruler of 320 million Americans coast-to-coast, is a majority of the nine lawyers on the Supreme Court. ...

When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, every State limited marriage to one man and one woman, and no one doubted the constitutionality of doing so. That resolves these cases. ...

Since there is no doubt whatever that the People never decided to prohibit the limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples... The public debate over same-sex marriage must be allowed to continue.

But the Court ends this debate, in an opinion lacking even a thin veneer of law. Buried beneath the mummeries and straining-to-be-memorable passages of the opinion is a candid and startling assertion: No matter what it was the People ratified, the Fourteenth Amendment protects those rights that the Judiciary, in its 'reasoned judgment,' thinks the Fourteenth Amendment ought to protect.

This is a naked judicial claim to legislative -- indeed, super-legislative -- power; a claim fundamentally at odds with our system of government. ... A system of government that makes the People subordinate to a committee of nine unelected lawyers does not deserve to be called a democracy.

Judges are selected precisely for their skill as lawyers; whether they reflect the policy views of a particular constituency is not (or should not be) relevant. ...

Not surprisingly then, the Federal Judiciary is hardly a cross-section of America. Take, for example, this Court, which consists of only nine men and women, all of them successful lawyers who studied at Harvard or Yale Law School. Four of the nine are natives of New York City. Eight of them grew up in east- and west-coast States. Only one hails from the vast expanse in-between. Not a single Southwesterner or even, to tell the truth, a genuine Westerner (California does not count). Not a single evangelical Christian (a group that comprises about one quarter of Americans), or even a Protestant of any denomination. The strikingly unrepresentative character of the body voting on today's social upheaval would be irrelevant if they were functioning as judges, answering the legal question whether the American people had ever ratified a constitutional provision that was understood to proscribe the traditional definition of marriage. But of course the Justices in today's majority are not voting on that basis; they say they are not. And to allow the policy question of same-sex marriage to be considered and resolved by a select, patrician, highly unrepresentative panel of nine is to violate a principle even more fundamental than no taxation without representation: no social transformation without representation.

But what really astounds is the hubris reflected in today's judicial Putsch. The five Justices who compose today's majority are entirely comfortable concluding that every State violated the Constitution for all of the 135 years between the Fourteenth Amendment's ratification and Massachusetts' permitting of same-sex marriages in 2003. They have discovered in the Fourteenth Amendment a 'fundamental right' overlooked by every person alive at the time of ratification, and almost everyone else in the time since.

They are certain that the People ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to bestow on them the power to remove questions from the democratic process when that is called for by their 'reasoned judgment.'

The opinion is couched in a style that is as pretentious as its content is egotistic. It is one thing for separate concurring or dissenting opinions to contain extravagances, even silly extravagances, of thought and expression; it is something else for the official opinion of the Court to do so.

Of course the opinion's showy profundities are often profoundly incoherent. ... [The majority declares] 'The nature of marriage is that, through its enduring bond, two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality [reads the opinion.' (Really? Who ever thought that intimacy and spirituality [whatever that means] were freedoms? And if intimacy is, one would think Freedom of Intimacy is abridged rather than expanded by marriage. Ask the nearest hippie. Expression, sure enough, is a freedom, but anyone in a long-lasting marriage will attest that that happy state constricts, rather than expands, what one can prudently say.) ...

The world does not expect logic and precision in poetry or inspirational pop-philosophy; it demands them in the law. The stuff contained in today's opinion has to diminish this Court's reputation for clear thinking and sober analysis.

In his concluding paragraph, the conservative stalwart issues a warning:

"Hubris is sometimes defined as o'erweening pride; and pride, we know, goeth before a fall. The Judiciary is the 'least dangerous' of the federal branches because it has 'neither Force nor Will, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm' and the States, 'even for the efficacy of its judgments.' With each decision of ours that takes from the People a question properly left to them -- with each decision that is unabashedly based not on law, but on the 'reasoned judgment' of a bare majority of this Court -- we move one step closer to being reminded of our impotence."

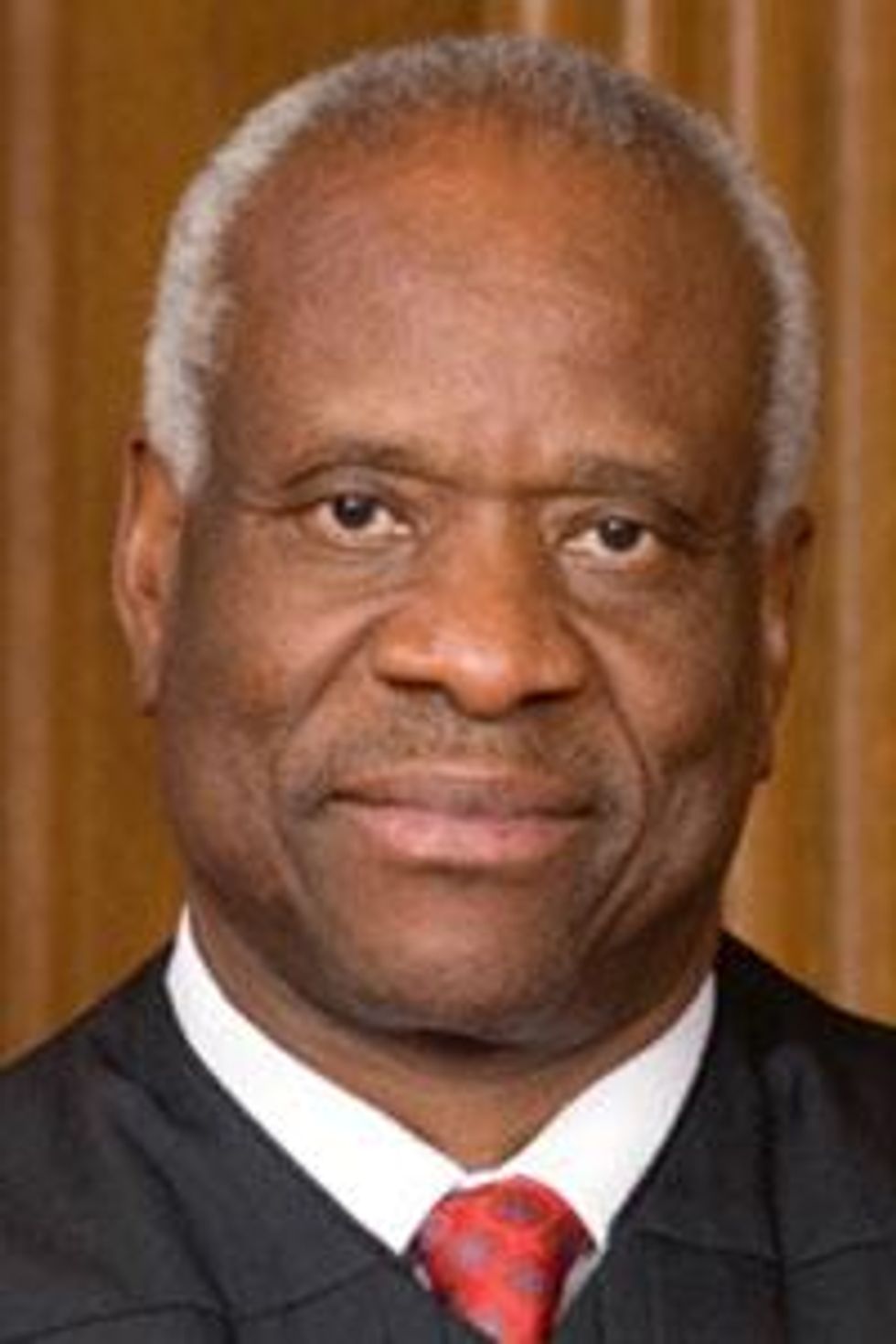

Justice Clarence Thomas: Dignity doesn't come from the government, but religious freedom is now at risk.

Justice Clarence Thomas: Dignity doesn't come from the government, but religious freedom is now at risk.

"The Court's decision today is at odds not only with the Constitution, but with the principles upon which our Nation was built. ...

The majority invokes our Constitution in the name of a 'liberty' that the Framers would not have recognized, to the detriment of the liberty they sought to protect. Along the way, it rejects the idea -- captured in our Declaration of Independence -- that human dignity is innate and suggests instead that it comes from the Government. ...

In the American legal tradition, liberty has long been understood as individual freedom from governmental action, not as a right to a particular governmental entitlement. ...

Whether we define 'liberty' as locomotion or freedom from governmental action more broadly, petitioners have in no way been deprived of it.

Petitioners cannot claim, under the most plausible definition of 'liberty,' that they have been imprisoned or physically restrained by the States for participating in same-sex relationships. To the contrary, they have been able to cohabitate and raise their children in peace. They have been able to hold civil marriage ceremonies in States that recognize same-sex marriages and private religious ceremonies in all States. They have been able to travel freely around the country, making their homes where they please. Far from being incarcerated or physically restrained, petitioners have been left alone to order their lives as they see fit.

Petitioners do not ask this Court to order the States to stop restricting their ability to enter same-sex relationships, to engage in intimate behavior, to make vows to their partners in public ceremonies, to engage in religious wedding ceremonies, to hold themselves out as married, or to raise children. The States have imposed no such restrictions. Nor have the States prevented petitioners from approximating a number of incidents of marriage through private legal means, such as wills, trusts, and powers of attorney.

Instead, the States have refused to grant them governmental entitlements. ...

To the extent that the Framers would have recognized a natural right to marriage that fell within the broader definition of liberty, it would not have included a right to governmental recognition and benefits. Instead, it would have included a right to engage in the very same activities that petitioners have been left free to engage in ... without government interference. ...

As a philosophical matter, liberty is only freedom from governmental action, not an entitlement to governmental benefits. And as a constitutional matter, it is likely even narrower than that, encompassing only freedom from physical restraint and imprisonment. ...

The majority's inversion of the original meaning of liberty will likely cause collateral damage to other aspects of our constitutional order that protect liberty.

Aside from undermining the political processes that protect our liberty, the majority's decision threatens the religious liberty our Nation has long sought to protect. The history of religious liberty in our country is familiar: Many of the earliest immigrants to America came seeking freedom to practice their religion without restraint. ...

In our society, marriage is not simply a governmental institution; it is a religious institution as well. Today's decision might change the former, but it cannot change the latter. It appears all but inevitable that the two will come into conflict, particularly as individuals and churches are confronted with demands to participate in and endorse civil marriages between same-sex couples.

The majority appears unmoved by that inevitability. It makes only a weak gesture toward religious liberty in a single paragraph...

Had the majority allowed the definition of marriage to be left to the political process -- as the Constitution requires -- the People could have considered the religious liberty implications of deviating from the traditional definition as part of their deliberative process. Instead, the majority's decision short-circuits that process, with potentially ruinous consequences for religious liberty. ...

Perhaps recognizing that these cases do not actually involve liberty as it has been understood, the majority goes to great lengths to assert that its decision will advance the 'dignity' of same-sex couples.

The flaw in that reasoning, of course, is that the Constitution contains no "dignity" Clause, and even if it did, the government would be incapable of bestowing dignity. Human dignity has long been understood in this country to be innate. ...

The corollary of that principle is that human dignity cannot be taken away by the government. Slaves did not lose their dignity (any more than they lost their humanity) because the government allowed them to be enslaved. Those held in internment camps did not lose their dignity because the government confined them. And those denied governmental benefits certainly do not lose their dignity because the government denies them those benefits. The government cannot bestow dignity, and it cannot take it away."

Justice Samuel Alito: This dangerous decision will silence the people who believe in so-called traditional marriage.

Justice Samuel Alito: This dangerous decision will silence the people who believe in so-called traditional marriage.

"Until the federal courts intervened, the American people were engaged in a debate about whether their States should recognize same-sex marriage.

The question in these cases, however, is not what States should do about same-sex marriage but whether the Constitution answers that question for them. It does not. The Constitution leaves that question to be decided by the people of each State.

The Constitution says nothing about a right to same-sex marriage, but the Court holds that the term 'liberty' in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment encompasses this right. Our Nation was founded upon the principle that every person has the unalienable right to liberty, but liberty is a term of many meanings. ... For today's majority, it has a distinctively postmodern meaning.

For today's majority, it does not matter that the right to same-sex marriage lacks deep roots or even that it is contrary to long-established tradition. The Justices in the majority claim the authority to confer constitutional protection upon that right simply because they believe that it is fundamental. ...

This understanding of marriage, which focuses almost entirely on the happiness of persons who choose to marry, is shared by many people today, but it is not the traditional one. For millennia, marriage was inextricably linked to the one thing that only an opposite-sex couple can do: procreate. ...

Today's decision usurps the constitutional right of the people to decide whether to keep or alter the traditional understanding of marriage. The decision will also have other important consequences.

It will be used to vilify Americans who are unwilling to assent to the new orthodoxy. In the course of its opinion, the majority compares traditional marriage laws to laws that denied equal treatment for African-Americans and women. The implications of this analogy will be exploited by those who are determined to stamp out every vestige of dissent. ...

I assume that those who cling to old beliefs will be able to whisper their thoughts in the recesses of their homes, but if they repeat those views in public, they will risk being labeled as bigots and treated as such by governments, employers, and schools. ...

By imposing its own views on the entire country, the majority facilitates the marginalization of the many Americans who have traditional ideas. Recalling the harsh treatment of gays and lesbians in the past, some may think that turnabout is fair play. But if that sentiment prevails, the Nation will experience bitter and lasting wounds. ...

If a bare majority of Justices can invent a new right and impose that right on the rest of the country, the only real limit on what future majorities will be able to do is their own sense of what those with political power and cultural influence are willing to tolerate. Even enthusiastic supporters of same-sex marriage should worry about the scope of the power that today's majority claims. ...

Most Americans -- understandably -- will cheer or lament today's decision because of their views on the issue of same-sex marriage. But all Americans, whatever their thinking on that issue, should worry about what the majority's claim of power portends."

Chief Justice John Roberts: This issue should have been decided by the people, not the Court.

Chief Justice John Roberts: This issue should have been decided by the people, not the Court.  Justice Antonin Scalia: Today's decision is irresponsible, "impotent," and an affront to American democracy.

Justice Antonin Scalia: Today's decision is irresponsible, "impotent," and an affront to American democracy.  Justice Clarence Thomas: Dignity doesn't come from the government, but religious freedom is now at risk.

Justice Clarence Thomas: Dignity doesn't come from the government, but religious freedom is now at risk. Justice Samuel Alito: This dangerous decision will silence the people who believe in so-called traditional marriage.

Justice Samuel Alito: This dangerous decision will silence the people who believe in so-called traditional marriage.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes