Throughout his remarkable life, NBA legend and activist Bill Russell was always referred to as a "giant," not only because of his 6 '10" height but also because of his record-setting 11 NBA championships (a U.S. sports record) with the Boston Celtics. Mind you, he only played in the league 13 years. Russell also won five Most Valuable Player awards, was a 12-time NBA all-star, and was a U.S. gold medalist at the 1956 Olympics.

And he led the University of San Francisco to NCAA basketball tournament titles in 1955 and 1956. Russell was a record-setter as far back as high school.

I got a firsthand account of Russell's athletic artistry. When I spoke to legendary singer Johnny Mathis late last year, he told me the story of how he set a national high jump record as a sophomore in high school. He beat the record that had been set the year before by...you guessed it, Bill Russell. Mathis and Russell were both from the San Francisco Bay Area, and Mathis told me that he and Russell, despite being adversaries on the athletic field, became close friends for life.

However, Russell's lifelong fight for civil rights and social justice might be his most impressive accomplishment. It was primarily Russell's advocacy for equal rights that prompted President Barack Obama to award him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, our nation's highest civilian honor.

Throughout his career, Russell faced bigotry, even in largely liberal Boston, where he spent his career as a Celtic. His house was once robbed, and the perpetrators left racist graffiti etched on the walls. And when two of his Black teammates were refused service in a Kentucky coffee shop, he famously led a boycott of a scheduled exhibition game against the St. Louis Hawks, and his Black teammates as well as the Black players on the Hawks joined him.

He marched with Martin Luther King Jr., first meeting him in a hotel lobby before the March on Washington in 1963. When another civil rights leader, Medgar Evers, was shot and killed in Jackson, Miss., Russell traveled there and started the city's first integrated basketball camps. In the late 1960s and early '70s, he and Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Jim Brown were among the most prominent professional athletes speaking out for civil rights.

Russell refused to sign autographs because he felt he owed the fans nothing, and initially declining induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame; however, he gave back in so many other ways.

Having been a veteran activist for civil rights, Russell, at 83, bent down on his bad knees in 2017 to support Colin Kaepernick, then the San Francisco 49ers quarterback, when he took a knee during the national anthem. Kaepernick said that he could not stand to show pride in the flag of a country that oppressed Black people.

And as someone who stood for equal rights throughout his life and knew the intricacies of the fight, in 2014, Russell came out in support of gay athletes, saying that gay athletes' fight for equality and acceptance reminded him of some of the struggles Black athletes faced in the 1960s.

"It seems to me, a lot of questions about gay athletes were the same questions they used to ask about us," Russell said. And he had only one question for a gay athlete "Can he play?"

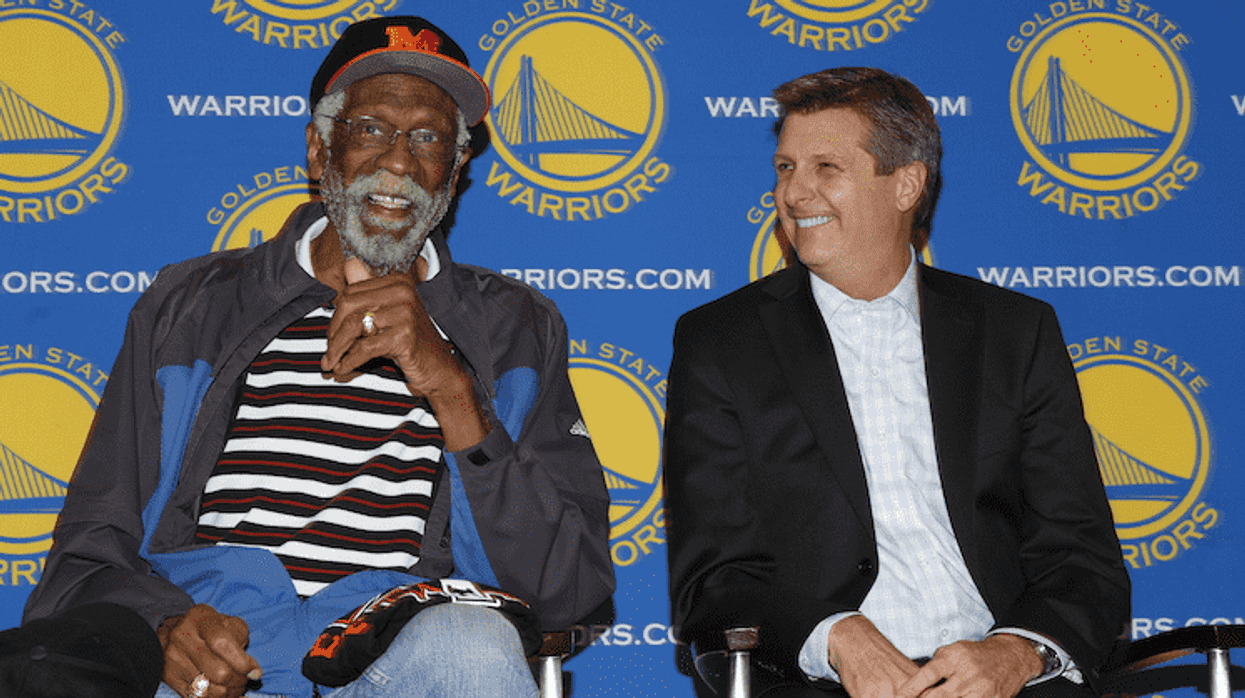

In 2011, Rick Welts, then Phoenix Suns president and CEO, was considering coming out of the closet. Welts has spent nearly 50 years in the NBA, starting as a ball boy in high school for the Seattle Supersonics. Most recently, Wells was president of the Golden State Warriors, helping them win three out of five championships from 2015 through 2019. He currently serves as a senior adviser to the team.

The first person Welts went to see for help in coming out was Bill Russell.

I reached out to Welts about his friendship with Russell and how Russell was instrumental in helping Welts announce that he was gay. Welts said the friendship started almost 50 years ago. "I think when talking about Bill, it's best to start at the beginning since the start of our friendship and the friendship itself, was pretty unconventional," he said.

Welts began his career in the NBA as a PR whiz, first doing a media relations internship with his hometown team, the Supersonics, in 1973. "You have to remember at that time the league was starting to come into its own and was still relatively small," Welts explained. "When I was president of the Suns, for example, we had 800 people in the organization, and when I interned in Seattle there were only 15 people with the front office."

It was during Welts's internship that he first got to know Russell. "It was a big deal when Bill was named the head coach of the Supersonics in 1973. As an intern, I had odd hours, and I sat at a desk at the end of a long hallway. Bill was an early riser, so his office was at the other end of the hallway, and for a while, he would come in, glance down the hall at me, and go into his office. I had no interaction with him until one day, Bill needed something.

"He came in early as usual and went into his office. Then about a minute later, since he didn't know my name, he poked his head out and said, 'Hey, white boy down the hall,' and he called me that until the very end. I'm going to miss that."

Welts emphasized that for some reason, Russell, who could be very mercurial and difficult to deal with, took a liking to him, and their friendship continued while Welts worked his way up the NBA ladder, including running PR and marketing for the league. "We brought Bill in for some merchandising opportunities, and we named the league championship Most Valuable Player award after him, and so each year until he wasn't able to do it because of health reasons, Bill was on hand to present the trophy to the winner," Welts recalled.

In late 2010, Welts was at a personal crossroads. "I had just ended a 14-year relationship mainly because I made the decision not to involve my partner in my professional life, and of course that was an ongoing problem until we broke up," he said. "I decided I had to make some changes, but because of my position with the Suns, I had no idea how the NBA players, fans, and other executives would react to me being gay. It had never been done before, not only in basketball, but the other professional leagues in the U.S."

Welts met in New York with a friend who worked in PR. They agreed that they'd work with Dan Barry of The New York Times to break the story. "My friend and I worked on a list of people that I would reach out to who would speak on my behalf, and at the top of the list was Bill," Welts noted.

Welts flew to Seattle to meet with Russell. "I'm not sure whether he knew I was gay or not, but I always remembered that when I was working with the Sonics Bill had lots of celebrity friends, some who were gay, so I suspected that he might be accepting, but there was no guarantee."

"I remember driving up his driveway, and walking to his door, and my heart was beating so fast," Welts recalled. "I knocked on the door, and this giant man wearing a Celtics hat opened the door, and it only made my heart beat faster. We went into a den,\ and sat down in two chairs, and the table between us had a picture of him with President Obama, and the president had signed it, 'You are my inspiration.' That was so intimidating."

After they sat down, Welts jumped right into it. "I told Bill that I was gay and that I was planning to come out and asked him to do something that he really hated doing, and that was talking to the media on my behalf. Without missing a beat, Bill said, 'Of course!' That was it. It was over, and for the next hour and half, we just talked about all the old times and laughed. He had a great cackle of a laugh, which I'm going to miss."

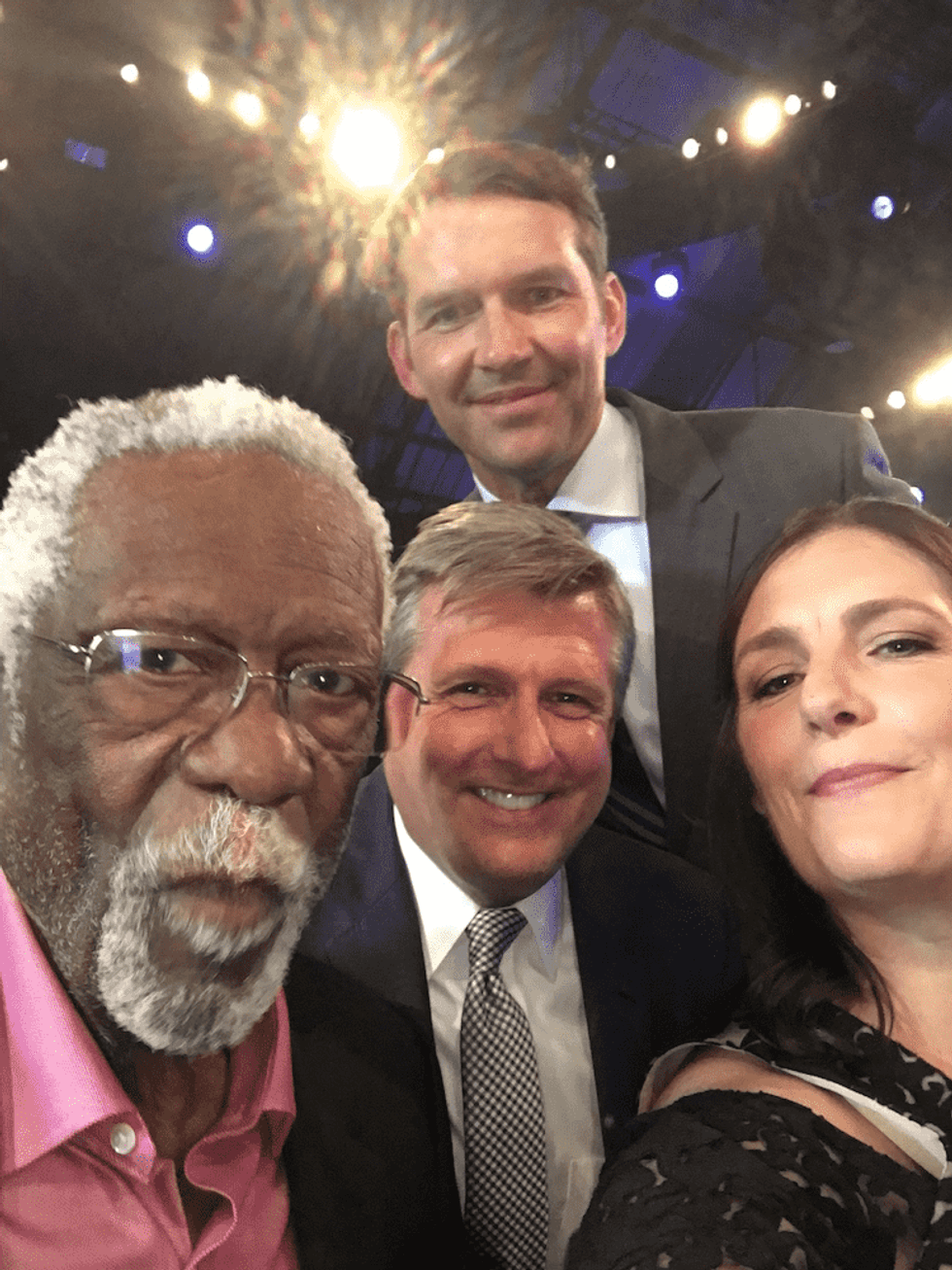

Welt's coming-out story appeared on page 1 of The New York Times in May of 2011, complete with supportive comments from Russell. Welts became the first prominent out gay executive in major sports history. When Welts was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018, he asked Russell to stand with him while he accepted the award.

What happened to the friendship with Russell after Wells came out? "It got much stronger and much deeper. We were able to talk about both of our families, not just his, since I had hidden so much in the past. Our friendship took on a whole new texture. I cannot explain why he took a liking to me and why we became the most unlikely of friends, but regardless, I feel enormously grateful that he became such a big part of my life. I will miss him."

"Bill was without question the greatest champion in the history of team sports," Welts continued. "Winning 11 championships in 13 years will never be done again by anyone. But Bill was probably most proud of his lifetime commitment to social justice. In the pantheon of athletes fighting for equal rights, Bill is at the top."

John Casey is editor at large for The Advocate.

Views expressed in The Advocate's opinion articles are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, Equal Pride.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes