Jann Wenner, the mercurial cofounder and longtime editor in chief of Rolling Stone magazine, hoped to cement his legacy with his latest book, The Masters, a collection of his interviews with rock stars like Mick Jagger and Bruce Springsteen. Instead, he sullied his reputation by admitting what has been whispered about for years — that he doesn't think all that much of artists who are women or artists who are people of color.

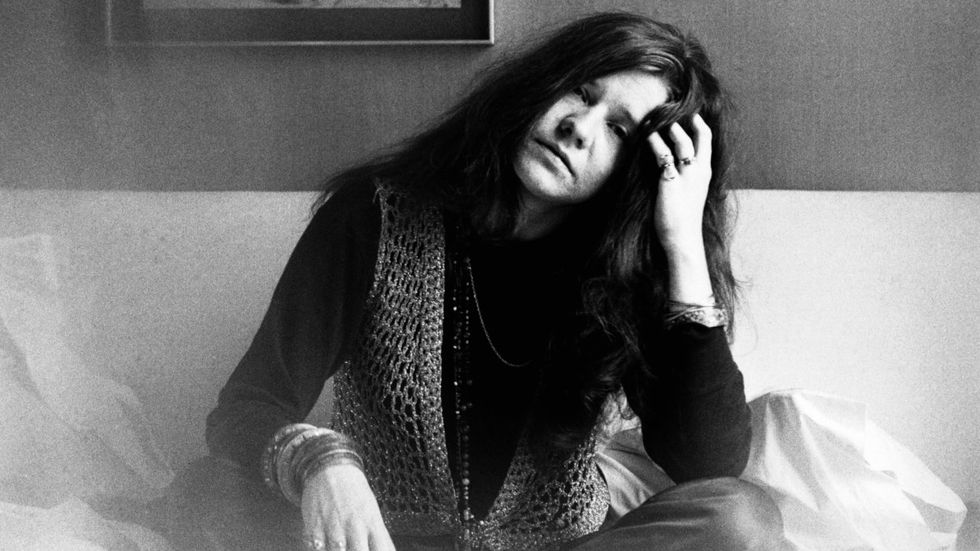

Wenner’s admission came in a recent interview with The New York Times, when he was asked to expound on why The Masters only includes interviews with white male musicians. In the book’s introduction, Wenner wrote that female and POC musicians were not in his “zeitgeist." Times writer David Marchese (a former reporter for Rolling Stone) asked how is it possible that a man who lived through Janis Joplin, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Nicks, Stevie Wonder, Carole King, and Madonna (not to mention Tina Turner, Nina Simone, Carlos Santana, Bob Marley, and Beyoncé) does not have any of these icons in his zeitgeist?

“When I was referring to the zeitgeist, I was referring to Black performers, not to the female performers, OK? Just to get that accurate,” Wenner responded. “The selection was not a deliberate selection. It was kind of intuitive over the years; it just fell together that way. The people had to meet a couple criteria, but it was just kind of my personal interest and love of them. Insofar as the women, just none of them were as articulate enough on this intellectual level.”

Marchese pushed back, incredulous that he would not think Mitchell, for example, was articulate on an intellectual level.

“It’s not that they’re not creative geniuses. It’s not that they’re inarticulate, although, go have a deep conversation with Grace Slick or Janis Joplin. Please, be my guest. You know, Joni was not a philosopher of rock ’n’ roll. She didn’t, in my mind, meet that test. Not by her work, not by other interviews she did. The people I interviewed were the kind of philosophers of rock.

"Of Black artists — you know, Stevie Wonder, genius, right? I suppose when you use a word as broad as ‘masters,’ the fault is using that word. Maybe Marvin Gaye, or Curtis Mayfield? I mean, they just didn’t articulate at that level.”

The response to Wenner’s verbal diarrhea was swift. The onetime media maven, who had not only Rolling Stone but Men’s Journal and Us Weekly under his control, was booted off the board of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, which he helped create. Wenner's son Gus, who now runs Rolling Stone, condemned his father's words in a statement. But for the elder Wenner's reputation, it feels like the mistake was putting definitive words behind decades of less direct actions.

As EIC of Rolling Stone, Wenner repeatedly put his (white, male) heroes on the cover, decades after the zeniths of their careers. Elevating Bob Dylan and George Harrison and Mick Jagger in the 2010s was a choice, but so was not doing the same with their female and POC peers like Aretha Franklin, Linda Ronstadt, or Celia Cruz (Wenner apparently had a soft spot for Jimi Hendrix, who did appear on a few 2010s Rolling Stone covers).

As any print editor knows, choosing magazine covers is a careful balancing act of relevance and commerce. While newsstand sales are not much of a consideration now (not many newsstands!), it certainly was during Wenner’s cover-choosing heyday. I doubt greatly that covers of Keith Richards in the 2010s were flying off the shelves — highlighting white male rock gods at the expense of their marginalized peers or legends from other musical genres was Wenner’s personal decision, one explained in his recent Times interview, and one that reverberated beyond a Baby Boomer in thrall of his own reflection and generation. As the head of a magazine that, to many, defined pop culture, Wenner helped shape the discussion on who was a “master” and who wasn’t. We now clearly know who Wenner thought was in that club and who was not.

Additionally, as an out editor, Wenner surprisingly doesn't seem to hold the same reverence for LGBTQ+ musical icons (Elton John, Freddie Mercury, Dusty Springfield, Whitney Houston, etc.) as he does for his mostly hetero-identifying heroes. Judy Wieder, a former music journalist and the first female editor in chief of The Advocate, shared her recollections of Wenner.

"I spent many visits to Jann’s New York office when I was editor in chief of The Advocate during the '90s, trying to get him to come out publicly as a gay man," Wieder posted on Facebook. "He complimented my 'important work,' signed his coffee table book for me, and was very generous with his private conversations. But he refused to talk publicly. Too big a risk for his [rock & roll] career."

Wenner's vice grip on culture and his warped view of genius may have had other repercussions. In the last interview given by Janis Joplin, who Wenner explicitly insulted in the Times, the bisexual blues goddess lamented coverage she received in Rolling Stone, which Wenner controlled at the time. Joplin, speaking to The Village Voice's Howard Smith four days before her heroin overdose death in October 1970, was reminded of an aborted interview between them.

"We were supposed to do an interview, you know, a long time ago," Smith said. "And some article putting you down in Rolling Stone had just come out. You got very upset about it. Are you still that upset when you are still put down in any articles?"

"I should be able to get past that, you know, I mean girls want to be reassured," Joplin responded. "That's not to say all people don't, but I think women especially. Even though I know those are just assholes who don't know what they're talking about and I just should just continue with my music, you know, and let them come to the show and listen or go home and beat off; I don't care what they do. I should be able to do that but in my insides it really hurts ... it's silly."

"I remember at the time you were very upset," Smith added.

"Well, it was a very pretty heavy time for me," Joplin said, "and it was very important whether people were going to accept me or not."

Neal Broverman is editorial director at equalpride, publisher of The Advocate.

Views expressed in The Advocate’s opinion articles are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, equalpride.