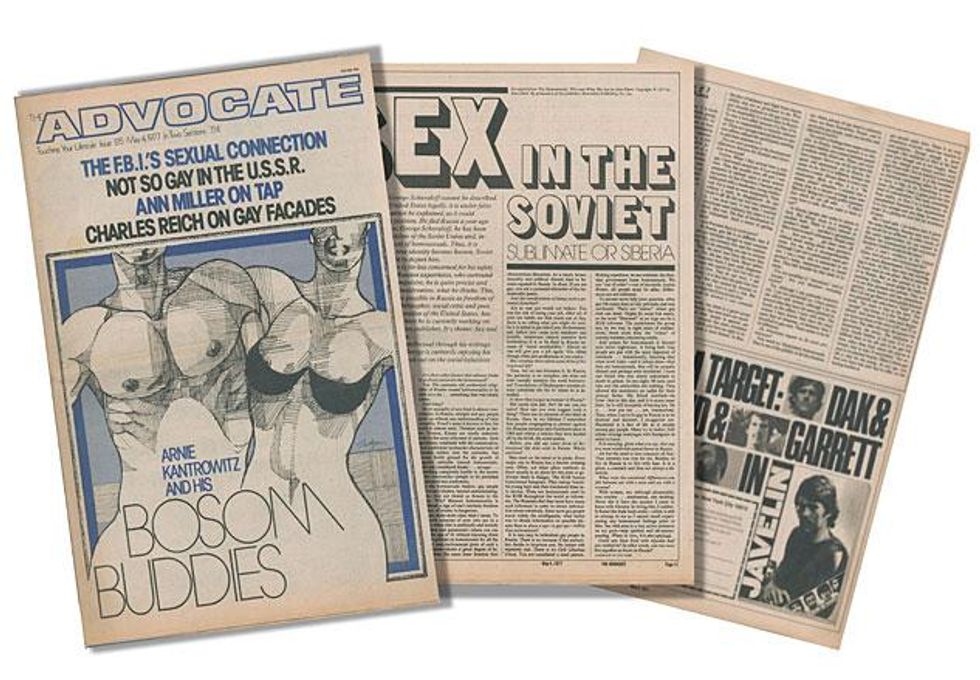

In May of 1977, The Advocate published an interview with Gennady Smakov, a gay intellectual who fled Soviet persecution just two years prior, seeking asylum in the United States. Having fled a country where free speech did not exist and where homosexuality was harshly criminalized, the Soviet author risked his life to escape the widespread oppression that shaped Soviet society in the 1970s.

But that was nearly four decades ago, when communism was perceived as America's great threat and homosexuality was still classified by the American Psychological Association as a mental disorder. In the four decades since Smakov's dramatic escape, the world has itself changed dramatically, especially for LGBT people around the globe, both in the United States, and within the boundaries of its once-bitter enemy.

Fourteen years after Smakov's own immigration, the Berlin Wall fell with a ring of democracy that quickly echoed across the Eastern Bloc, in the same vein that marriage equality now ripples across America. When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a key section of the so-called Defense of Marriage Act last summer, the ruling ushered in a wave of progress already long reflected in the attitude of an evolving American public, the vast majority of which overwhelmingly support equal rights for LGBT people throughout the nation.

But the passage of time doesn't always align itself with progress. The American evolution isn't always mirrored by free societies developing around it. The same summer that U.S. courts ruled it unconstitutional to deny federal recognition to same-sex couples, the Kremlin began to tighten its grip on LGBT citizens, invoking a nationwide ban on "gay propaganda" last June.

But the crackdown on LGBT people in Russia isn't exactly news to anyone who's lived in the nation over the last century. Although the 2014 Winter Olympics have trained an international spotlight upon Russia, persecution has always been a way of life for gay men and women in this supposedly modern society.

THE REBEL

Smakov described experiencing a uniquely Russian brand of homophobia in 1975. "Such ignorance, combined with the conservative, even conformist tendencies characteristic of Russian culture over the centuries, has proven fertile ground for the growth of negative attitudes toward homosexuals," Smakov wrote nearly 40 years ago.

In the path Smakov laid decades ago, a new flock of Russians are now fleeing a desperate situation. Due to the recent rise in state-sanctioned LGBT persecution and the unchecked, hate-fueled violence surging in the former Soviet Union, applications for asylum are flooding into the U.S. immigration office. Though these numbers alone show a devastating trend, the voices of these persecuted Russians tell a vivid story that hauntingly echoes the one Smakov shared with The Advocate decades ago. Even 40 years later, much of the interview could have been ripped from the pages of this month's edition.

When acclaimed journalist Alan Ebert sat down with Smakov in 1977, he did so unaware of the man's true name and circumstance. Although Ebert didn't know it at the time, the author-turned-psychotherapist now confirms that the subject of his interview was Smakov, who then identified as George Schuvaloff. He had fled the Soviet Union under false pretense, seeking asylum in the United States to avoid life under communist rule that outlawed homosexuality and often punished it with life in prison, or even death.

When acclaimed journalist Alan Ebert sat down with Smakov in 1977, he did so unaware of the man's true name and circumstance. Although Ebert didn't know it at the time, the author-turned-psychotherapist now confirms that the subject of his interview was Smakov, who then identified as George Schuvaloff. He had fled the Soviet Union under false pretense, seeking asylum in the United States to avoid life under communist rule that outlawed homosexuality and often punished it with life in prison, or even death.

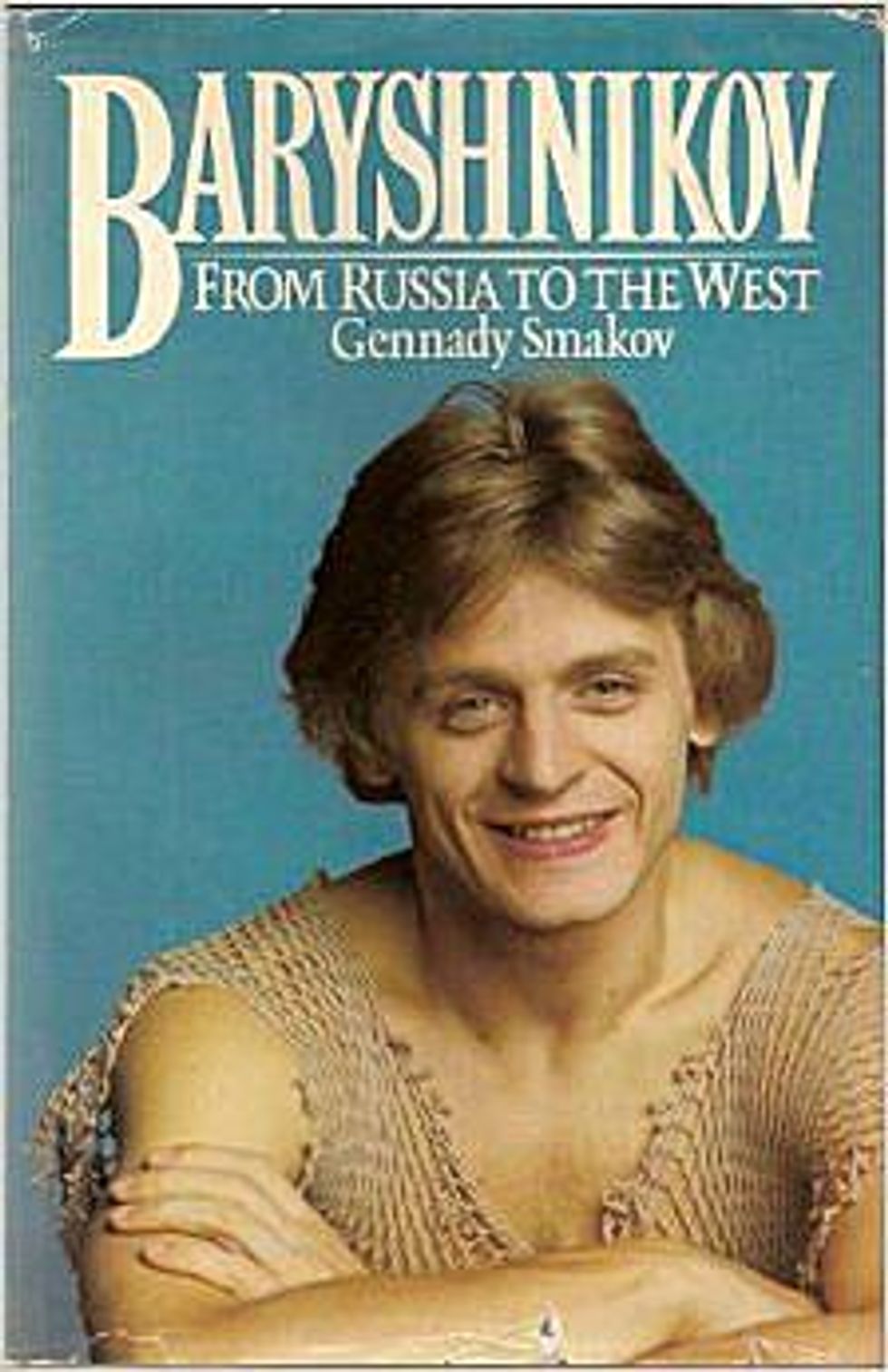

Smakov was an author, poet, and outspoken social critic of the Soviet government. Smakov also happened to be an expert on Russian ballet, penning the biography of famous dancer and fellow defector, Mikhail Baryshnikov.

In the candid interview, Smakov spoke at length about what it meant to be a gay man living in the communist state. and the degree to which homosexuality was rooted out by Soviet authorities and secret police. He described his native country as a place in which "gay people are not supposed to exist."

In the two-page Advocate interview, originally intended for Ebert's book, Homosexuals, Smakov described gay life in the Soviet Union as one cloaked in secrecy, where gay people were forced to live double lives, constantly fearing social alienation at the best, and arrest, imprisonment, and death at the worst. Smakov described a culture where even two unrelated men living together aroused enough suspicion to warrant their swift disappearance.

"To the bureaucratic leaders, gay people seem totally bizarre, beyond understanding," Smakov said in 1977. "Worse, they are viewed as threats to the system. Why? Because homosexuality is considered a sign of one's intrinsic freedom and that, of course, is dangerous."

While so much in Russia has changed since the late author risked his life to taste freedom abroad, one eerily familiar thread has remained constant throughout nearly a half-century of state-sponsored LGBT persecution. The constant is a man, who now runs the country.

THE MAN

THE MAN

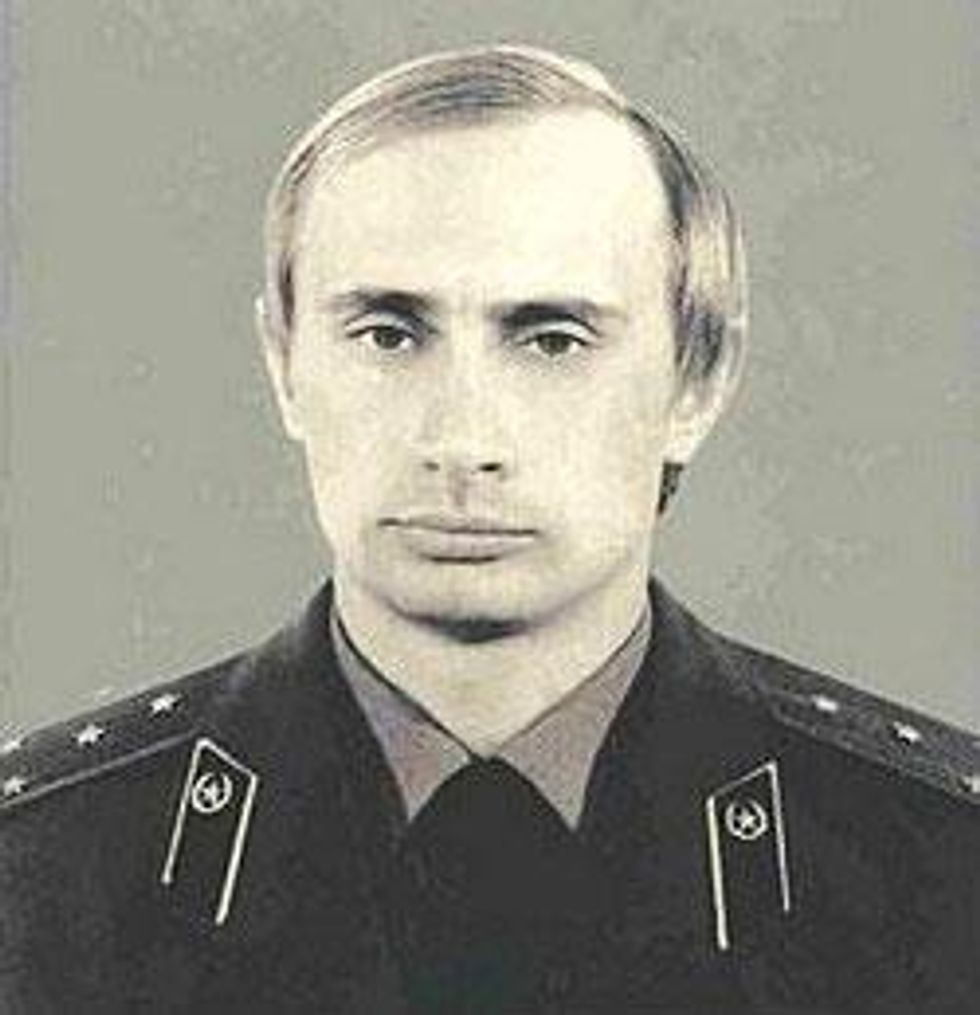

The same year that Smakov was smuggled out of the Soviet Union, a fresh-faced, 25-year-old named Vladimir Putin was in Leningrad completing his year-long indoctrination with the KGB, the very state agency charged with eliminating homosexuality and squashing dissent during the Soviet reign. Putin's rise to political prominence in the last quarter-century from KGB officer to president is nothing short of legendary, even outside of Russia.

Putin has worked to ensure that his personal story has become intrinsic to the fate of a nation, and now finds himself facing some measure of domestic outcry over allegations of corruption and cronyism. These charges have followed Putin since his days as deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, where he'd been implicated in several investigations revolving around the use KGB connections to launder money after the breakup of the Soviet state.

According to Bloomberg, Putin has a long-standing and ongoing habit of awarding lucrative business contracts to close friends -- including more than 20 surrounding the Sochi Olympic Games. In preparing for the Games, Bloomberg reports, the Kremlin has funneled billions of dollars to the pockets of Putin's childhood friends through Olympic projects and contracts. But few in Russia are surprised by such dealings anymore. Many still question his legitimacy as the rightful leader of Russia.

Having been elected amidst wide-scale opposition -- and legitimate concerns of election fraud -- to an unprecedented third term, President Putin returned as head of the conservative United Russia Party in 2012. Within a year, Forbes recognized the hyper-masculine cult hero as the "most powerful man in the world," just as the Democracy Index was downgrading the talisman's regime to "authoritarian."

Despite insinuations by foreign media that Putin's popularity is dwindling, the reality is his popularity in polling has not waned since the last election. As recently as November 2013, the Levada Center, Russia's leading independent polling agency, found that Putin's approval rating remained "broadly unchanged for the past two years."

THE BAN

The summer of 2013 was a particularly daunting one for LGBT people living in Russia. In June the State Duma, at the behest of President Putin, approved a national law that banned "propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations" in areas visible to minors. Not one member of Russia's parliament cast a vote in opposition to the law, which Putin signed in late June. At its core, the so-called gay propaganda ban prohibits dissemination of any material supportive of LGBT rights, or any discussion that contends LGBT people are equal to heterosexuals. As Putin has pointed out in numerous interviews before the Sochi Games, the law does not technically make it illegal to be gay -- but it outlaws any positive depiction or support for LGBT people, and it's already been enforced against those brave enough to unfurl a rainbow flag on Russian soil. While some of the language of oppression has shifted to become more nuanced since the dark days of the KGB, the comparisons to Soviet-era persecution are glaring.

When the "propaganda ban" was challenged and upheld by Russia's Constitutional Court in October, the court reasoned that national lawmakers had a duty to "take measures to protect children from information, propaganda and campaigns that can harm their health and moral and spiritual development." Arguably bolstered by this ruling, Putin's United Russia Party continues to advance its antigay agenda.

Last fall, members of the United Russia party introduced a proposal that would forcibly remove children from the homes of their gay and lesbian parents. The bill has been temporarily shelved, presumably to avoid discussing the contentious issue as the world's attention is turned to Russia during the Winter Olympics. But the bill published on the Duma's website proposes that the government strip parents of custody if they practice "nontraditional sexual relations," and equates those relationships with child abuse, alcoholism, and incest as justifiable reasons to revoke parental rights.

But it's not simply the antigay agenda that concerns so many both in and outside of Russia; it's the apparent return of Soviet-era tactics that leave activists fearing for their lives. As Smakov detailed in 1977, the Soviet government had methods for quieting dissent -- and remember that Putin wasn't always a politician.

As revered LGBT activist, journalist, and mother Masha Gessen is quick to point out in her influential book, Man Without A Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin, a troubling number of journalists and editors have been killed or disappeared during Putin's reign. Gessen's friend, Galina Starovoitova, was murdered in St. Petersberg, and other journalists critical of the government still live in fear. While independent journalists face intimidation, Putin decreed in December that former Kremlin-backed news agency RIA Novosti would be abolished, and replaced with state-owned Russia Today, headed by Dmitry Kiselev, whom the BBC calls a "keen Kremlin supporter" and who The Economist labeled "Russia's chief propagandist."

In addition to prosecuting activists under the "propaganda" law, the government is using propaganda of its own to combat a network of pro-LGBT activists. In its ongoing fight to disband the organizations, the United Russian Party paints the groups as enemies of the state, encouraged by a 2012 law that required any non-government organization receiving money from abroad to register as a "foreign agent." Since domestic funding for LGBT groups is increasingly hard to come by in Putin's Russia, the organizations defending the embattled LGBT community must often turn to international aid, leaving those groups vulnerable to investigation and prosecution under espionage laws.

In one of the most blatant examples of the country's attack on activist groups, the government spied on a meeting between Russian LGBT activists and four international human rights organizations, including the Human Rights Campaign. The government then broadcast the secretly recorded audio on a state-sponsored TV station, according to BuzzFeed, and warned the meeting was a "threat to Russia" from the "homosexualists who attempt to infiltrate our country."

THE REAL CRIMINALS

If antigay legislation is well documented in Russia's parliamentary records, the violence and climate of fear that stems from such state-sanctioned persecution is generally ignored by mainstream Russian media. Last year, the violence reached a new level when vigilante groups of Neo-Nazis claiming to root out pedophilia lured gay men into private apartments, then filmed as the men were beaten, humiliated, and publically shamed. The videos received thousands of views on Russian social media site Vkontakte, and went viral globally. Although the faces of the assailants are clearly visible in the videos, to date, only the group's leader has been arrested -- in connection to charges of extremism unrelated to the antigay assaults.

A popular gay club in Moscow has been the target of repeated attacks, most recently when attackers dismantled the club's roof, just weeks after patrons inside the club were exposed to a harmful gas sprayed into the club by "malefactors." That attack occurred less than two weeks after the club was sprayed with bullets.

The victims of these crimes -- and dozens more -- are often young adults, many of whom do not report the crime, understandably hesitant to believe the assault will be prosecuted by the very law enforcement officials who view the victims as criminals. When a meeting of LGBT youth was violently disrupted by masked men brandishing a baseball bat and pneumatic gun last November, police who responded to the scene said they saw no evidence of a crime, despite one young person reportedly losing his sight after being shot in the eye.

THE ESCAPE

THE ESCAPE

When the government views LGBT victims as criminals, it only enables and perpetuates a climate of violence and fear, leaving many LGBT people with little recourse other than to go further underground. In many cases, the only option is to leave the country -- just as Smakov did almost 40 years ago.

But while Smakov's most difficult challenge was escaping the USSR to the United States, modern LGBT Russians face the daunting task of convincing the U.S. government or other countries to grant them asylum. Escaping an authoritarian communist regime is one thing, but seeking asylum from a developed, modern, and presumably democratic nation, like Russia, is quite another. The legal process of seeking asylum is constantly evolving, and the rules are always changing. Fortunately organizations and people like Aaron Morris can help.

"If Russia for a long time was not safe for LGBT people, it's a bit different now that the government is actually taking steps to enshrine that homophobia in the law," explains Morris, legal director of the New York City-based LGBT group Immigration Equality. "And I think that's especially scary for people in Russia who are trying to get out."

Immigration Equality works to end discrimination in U.S. immigration law, and helps win asylum for those fleeing persecution based on their sexual orientation, gender identity, or HIV status. The organization's staff has witnessed the impact of Russia's growing political and cultural homophobia. Morris reports a "dramatically higher increase" in asylum applications from Russia in the past year. Calls to the organization's free immigration advice hotline tripled in September alone.

Morris says Immigration Equality is currently working on 45 Russian cases. In fact, the organization received a 350 percent spike in inquiries, or requests for assistance.

"If the recent trend continues, then our Russian clients will become a much greater percentage of our overall case load than ever before. That seems certain," says Morris.

Morris predicted that the increased volume of requests for support will continue, which is why Immigration Equality's new "Russia Emergency Fund" was established. The fund raises money to ensure that every LGBT and HIV-positive Russian seeking asylum in the U.S. has competent legal representation.

In Russia, it's not only dangerous to be gay, but also separately dangerous to be HIV-positive because of the rampant stigmatization and equating of the two identities. "There's an association between those two things, where if you're gay often you're assumed to be HIV-positive," explains Morris. "Or, where if somebody discovers [your HIV status], they also assume that you're gay."

Being HIV-positive can be reason to be considered for asylum in the United States, if the asylum-seekers can prove that the government is severely stigmatizing those testing positive, or restricting medical access. While it's not difficult to prove one's HIV status, it's important for non-U.S. citizens to prove past persecution in order to win asylum in an immigration court.

(Sasha Kargalstev at a protest in New York)

Unfortunately, for many LGBT Russian immigrants, such documented examples of persecution are regularly relayed in police reports, or even worse, in hospital records. That's precisely what happened to Gleb Vakhrushev and Sasha Kargalstev, two Russians who successfully sought asylum in the U.S., with the assistance of Immigration Equality.

Both men were the victims of multiple savage and brutal attacks. Kargalstev was part of group beaten by both skinheads and police at an unsanctioned Moscow Pride rally in 2009. Both men are now safe in New York, where a growing group of LGBT Russian immigrants have formed a close-knit community, bonding over the horrifying experiences that are fast becoming less unique.

"It's getting worse and worse," says Kargalstev. "People are leaving the country -- all my friends left the country already. The reason is that Russia is dying and nothing will help. It's too late now."

Kargalstev won a scholarship to study at the New York Film Academy in 2010, then applied for asylum immediately after arriving in New York City. Similarly, Vakhrushev was able to secure a temporary student visa to make his way into the U.S., where he could safely apply for asylum and avoid returning to the violence and harassment he used to encounter daily.

"There was a time that Russia was better," says Vakhrushev. "Since the early '90s to middle 2000s, the situation was better than it is today."

THE POLITICS

Without hesitation, Vakhrushev said Russia is "an antigay society." While the blame could easily be placed on the government, he lays blame with his fellow countrymen, as well.

"Homophobia is an idea being forwarded by people, not government," Vakhrushev says. But he does fault the Putin regime for perpetuating the status quo in the interest of -- at its most innocuous -- political gain. In a severely conservative state, capitalizing on such a collective ideology is undoubtedly a means to capture and retain power. Classifying homosexuals as a direct threat to the family and the survival of the state is a popular political platform for the Kremlin, State Duma, and the increasingly powerful Russian Orthodox Church, and one that echoes dictatorships of the past.

"The government doesn't want to educate people, it wants to sell oil," says Vakhrushev. "It wants to be popular, and antigay law is very popular."

Smakov spoke candidly of the Soviet regime's labeling homosexuals as "threats to the system" and "dangerous" to the state. In the past, such rhetoric has been closely accompanied by a systematic constriction of free speech -- one of the many charges consistently leveled against Putin's United Russia party.

Almost unknowingly quoting the late Smakov, Vakhrushev speaks about gay life in Russia today as if it's still forbidden to exist.

"It's almost impossible to live your life there," Vakhrushev says. "Society has a long way of evolution. It's not a modern society yet, which is very sad of course."

But unlike his fellow expatriate, Vakhrushev doesn't hesitate to condemn his government's role in the deteriorating situation.

"It's not getting better, it's getting worse," he says. "Because of the United Russia party, and this LGBT legislation, people are being very violated against."

And that violation isn't limited to the Russian Federation, Vakhrushev contends. It's perpetuated by Russian-language media, much of which is overseen by the Kremlin.

"It's actually not only problematic in Russia, but all of the countries that speak Russian," explains Vakhrushev. "Those countries that watch or listen to Russian news channels that come from Russia, or even RT, based here in the U.S. They make people become intolerant to each other, they create an atmosphere where anybody who is a little different are not welcome."

THE GAMES

With the opening ceremonies for the 2014 Winter Olympics today, the eyes of the world will again be squarely focused on this oft ignored giant of a nation, possibly for reasons less to do with sport and more to do with justice and equality. The Games will be the first Olympics held in Russia since the breakup of the Soviet Union.

What happens on the slopes and on the ice will receive worldwide coverage, yet will have little lasting impact on a group of people still living in a fear strikingly similar to that of decades past. While activists are hoping to borrow the spotlight in Sochi, it's unknown just how much vocal dissent the Russian government will accept. After initially banning all demonstrations and protests in or around Sochi during the Olympics, the Kremlin recently announced that demonstrations would be allowed -- but only in a designated area several miles from any Olympic venue. Any demonstration must receive prior approval from the Kremlin, and cannot be directly related to the Winter Games.

It's doubtful that Olympic athletes themselves will be able to offer much support either, as Rule 50 of the International Olympic Committee's charter prohibits athletes from expressing political opinion, stating that "no kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas."

While Putin has said that visitors to Sochi this February will not be harassed or mistreated due to their sexual orientation, he's also stated that they must obey Russian law. Most recently, Putin reiterated his pledge that LGBT spectators would be welcomed in Sochi -- so long as they "leave the children in peace." With the nationwide ban on vaguely defined "propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations" already being enforced, media pundits covering the event are left in a vast legal grey area.

In a few weeks, after the Olympic and Paralympic games end in Sochi, many wonder what will happen to LGBT Russians when the international spotlight dims. Certainly, LGBT Russians will still be at the mercy of a government used to operating autonomously and without explanation. Will international media continue to highlight and report on the legitimate fears of LGBT Russian parents, who are waiting for their democratic government to declare them unilaterally unfit parents and forcibly remove their children?

Like Gennedy Smakov's flight from the USSR nearly 40 years ago, the current "dissenters," "disturbers," and "threats to the system," still struggle for peace in a nation that has come so far, and yet changed so little -- but perhaps today's radicals can agitate loudly enough that not even an autocratic regime headed by a former KGB agent can silence their protest.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Aaron Morris's title. He is the legal director of Immigration Equality, which is based in New York City. The Advocate regrets this error.

When acclaimed journalist Alan Ebert sat down with Smakov in 1977, he did so unaware of the man's true name and circumstance. Although Ebert didn't know it at the time, the author-turned-psychotherapist now confirms that the subject of his interview was Smakov, who then identified as George Schuvaloff. He had fled the Soviet Union under false pretense, seeking asylum in the United States to avoid life under communist rule that outlawed homosexuality and often punished it with life in prison, or even death.

When acclaimed journalist Alan Ebert sat down with Smakov in 1977, he did so unaware of the man's true name and circumstance. Although Ebert didn't know it at the time, the author-turned-psychotherapist now confirms that the subject of his interview was Smakov, who then identified as George Schuvaloff. He had fled the Soviet Union under false pretense, seeking asylum in the United States to avoid life under communist rule that outlawed homosexuality and often punished it with life in prison, or even death. THE MAN

THE MAN THE ESCAPE

THE ESCAPE

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered