A new documentary film chronicling the deeply troubling circumstances surrounding death of a young gay American student is raising questions about whether or not his supposed suicide was actually one of a spate of murders committed by "roving gangs of poofter-bashing youths" in the Sydney area the 1980s.

Steve Johnson lost his brother Scott, who was gay, in 1988 to what police in the Australian state of New South Wales quickly termed a suicide. In an instant, not only did Johnson lose his beloved brother, his newborn daughter lost an uncle whom she would never meet, while the world lost one of the most promising young mathematicians academia had seen in a generation.

Having aired recently on public television in the U.S. and available streaming online indefinitely, On the Precipice documents Steve Johnson's trek back to what many now believe is a murder scene half a world away, a murder that happened at a time that was vastly different from what gay men in Australia see today.

"Scott and I were very close," says Johnson, who in the 1990s built and sold a tech company called Johnson Grace, which developed some of the foundational algorithms that still underpin video compression today.

Johnson's brother Scott was also on a trajectory for great success. Though only 27 at the time of his death in 1988, Scott Johnson had already worked at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab on projects that resulted in the first images of the surface of Venus -- and he had already collaborated with several Harvard professors on the publication of landmark economics papers.

"We'll never know what we lost," laments Johnson. "Scott was brilliant and he was the sweetest man I've ever known."

In fact, the Tuesday following his supposed suicide, Scott was to have had a much-anticipated meeting with his professor. The day before his death, Scott's professor notified him that he had earned his doctorate. The facts around Scott's life at the time of his death made it all the harder for his family to accept the police's version of events.

"For a long time it was a complete mystery," Steve Johnson tells The Advocate. "Everyone had doubts."

Johnson has spent years reliving his thoughts and emotions from around the time of his brother's passing. He and others who knew and loved Scott felt nearly as much confusion as they did sadness during those early days following the tragedy.

Johnson recently wrote an op-ed for The Advocate about the fumbled investigations into his brother's death and other investigations of possibly misclassified suicides of gay men near Sydney.

"We were astonished," says Johnson, recalling the moment he received news of his brother's death. "His professor was completely destroyed. His boyfriend and his friends were completely at a loss."

Confusion and sadness notwithstanding, the months following the untimely death of Scott Johnson became years. Eventually, the years stacked up until it was nearly two decades since the New South Wales police had ruled Scott's death "just another suicide by a gay jumper." Then something unexpected happened.

The mother of a young man who refused to believe her son's death near one of the same beats (trails where gay men meet for anonymous sex) where Scott had died had convinced a local detective to look a littler harder into her son's case and those of a few other "gay jumpers." That detective, Steve Page, realized there was a pattern of similar deaths along northern Sydney's beachhead during the mid-to-late 1980s.

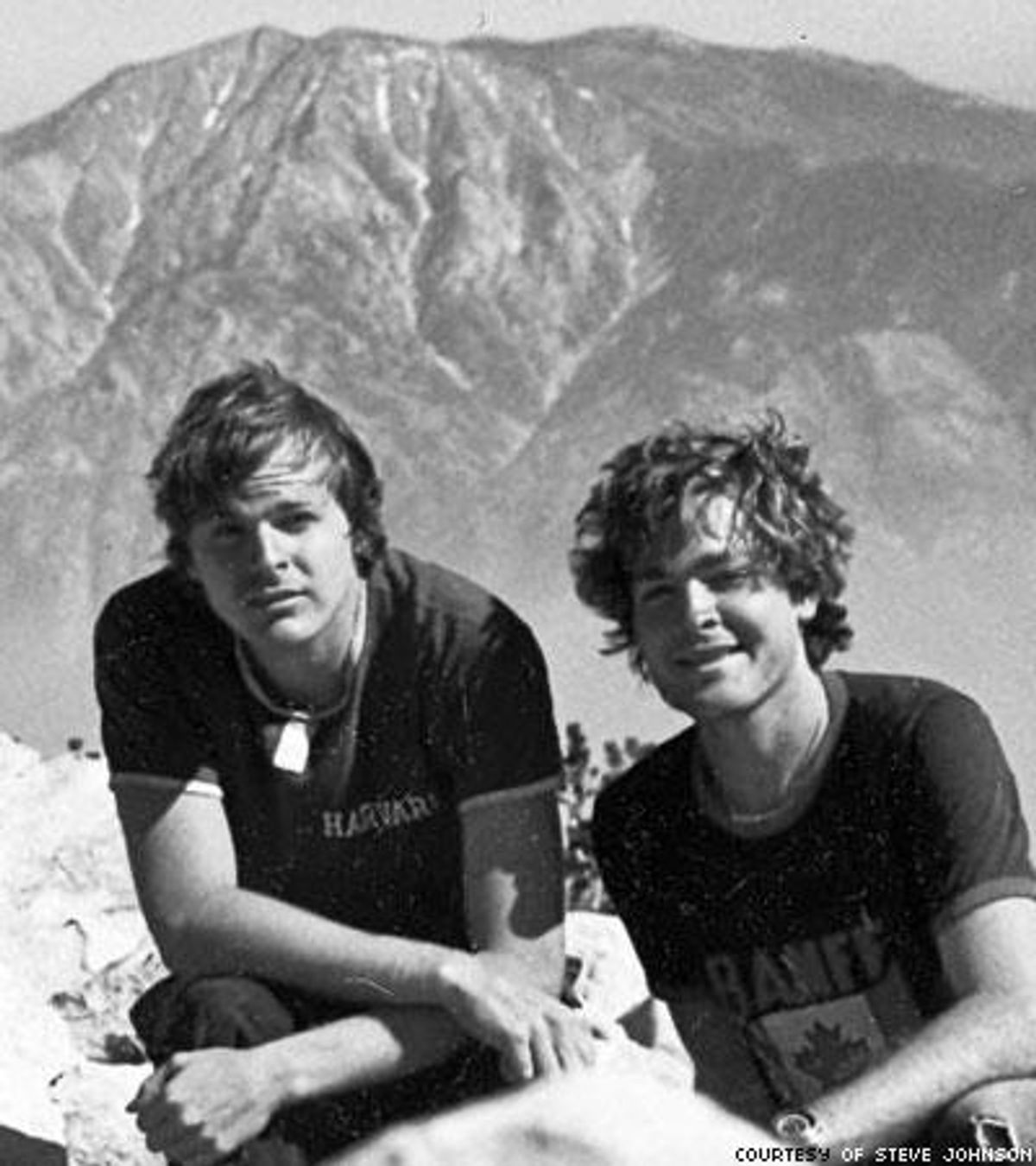

Left: Scott Johnson

Left: Scott Johnson

"I was told the place where Scott died was a place where homosexuals commonly jumped," Johnson says, recalling his meeting with the Australian police. "The police told the coroner there was nothing suspicious about Scott's death. To this day, they say the place Scott died wasn't a gay beat. Even though another man ended up with a knife in his back on that same rock where Scott was found the year before Scott died."

That man survived to tell the tale, and his attacker was apprehended. This incident vividly outlined the M.O. of the beats: Men would disrobe and welcome encounters but while vulnerable would occasionally get ambushed. Yet the police never disclosed this pattern to the Johnson family.

Things were different in Sydney in the 1980s, says Johnson. Gay men were still the objects of hate and homophobia among some locals. That hate, he says, sometimes turned violent.

"It was known that in 1988 it could be dangerous to be out of the closet, even in a place like Sydney," Johnson says. "Going to beaches and down to the gay beats at dusk after families were gone was popular with gay men looking for anonymous relationships. For some gay men who may not have felt safe being out of the closet at the time, that was the way they met other gay men."

But as it turns out, the beats of Manly and Bondi Beaches may at times have been hunting grounds for hate-filled predators in that era.

Shortly after being informed by police in Australia that has brother Scott had supposedly committed suicide by jumping onto a rock from a cliff high above Manly Beach, Johnson flew to Australia.

"They took me to the spot where Scott was supposed to have jumped," he recalls. "But as I learned later from police aerial photographs of the scene, the police didn't even take me to the right cliff."

Prompted by a 2005 story in an Australian newspaper about the mother who was certain her gay son had not willingly jumped to his death, Steve Johnson decided to return to Australia, sending his own investigator ahead to do some digging.

"I had doubts already," recalls Johnson. "I didn't think Scott's death was a suicide."

If police failed to take Steve Johnson to the correct cliff -- where his brother's naked body had been found by a boy and two spear fishermen below his neatly folded clothes -- what else did they have wrong? Johnson wondered nearly two decades later.

In fact, it appeared to Newsweek investigative reporter Daniel Glick that police decided on suicide as Scott Johnson's cause of death with little more evidence than learning from his boyfriend that Scott was gay and therefore "part of a group at high risk for infection" of HIV. He had also once mentioned considering jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. Glick, whom Steve Johnson hired in 2007 to look further into Scott's death, called the police investigation "perfunctory."

Police overlooked the fact that Scott's wallet was missing and refused to ask questions of locals who frequented the area. Glick learned that Scott's body was found above one of Manly's most popular gay beats, one that beat users said police sometimes raided.

The more Johnson learned about his brother's death and the NSW police's careless investigation -- not to mention their penchant for labeling deaths "nonsuspicious suicides" in what seemed to occur among young, gay men found dead on beaches -- the more committed he became to finding out the truth.

But he knew he would need to find a way to put more pressure on police to look again at his brother's case. That's when a little good luck struck with a call from producers at Australian Story.

The story of Scott Johnson's death, On the Precipice, was originally produced for Australian Story, the Australian Broadcasting Corp.'s hit public affairs show. It shed some new light on the mystery of Scott's death and on dozens of other cliffside deaths of gay men that New South Wales police had also deemed suicides or "misadventure."

Since the film aired on Australian Story, the Johnson family's journey of loss, confusion, and longing for the truth has made a marked turn.

"After the show aired, the New South Wales police asked to hold a press conference with me," says Johnson. "At the press conference, they said they would investigate Scott's case further."

While he remains optimistic that the full truth will be uncovered and that the police could still come around to the notion that there was something more nefarious about the dozens of deaths in the 1980s along Sydney's beachside "beats," he says the New South Wales police force is still unwilling to admit a pattern exists that cries out for a broader review.

Since Johnson made his millions, he has dedicated a significant portion of his fortune, time, and energy to learning the truth about his brother's last day alive. Scott's friends, folks who were around Sydney's gay community in the 1980s, former detective Page and, and investigative reporter Glick (who also investigated the murder of Jon-Benet Ramsey), say that Scott, feeling invigorated and joyful about having earned his Ph.D. after many years of hard work, went to a rocky beach in Manly knowing that it was also a place where he might connect with someone for sex. He was a young, fit, good-looking gay man whose boyfriend was out of the country. Right or wrong, the decision to go to the beach near Sydney's so-called beats may have gotten him murdered.

Now the police in New South Wales are offering a $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Scott Johnson's killer. Scott Johnson's case remains under investigation and has prompted calls from the media and the Australian public for the opening of dozens similar cases from the same period and geographic area. Recently, Steve Johnson discovered a newspaper story published the year before his brother's death.

"It says that three men were arrested and, in the same neighborhood where Scott died at a popular gay meeting place," Johnson wrote in an email to The Advocate that included a copy of the news brief, dated January 3, 1987. "This of course belies police insistence at the time that there was no violence in the area and no reason to believe foul play in my brother's death."

Recently Steve Johnson returned to the Matterhorn in Switzerland, where he and Scott had once climbed, where the brothers bonded on an even deeper level than they already had, growing up on welfare as children of a single mother. During their climb to the top of Matterhorn in 1984, Steve, who had only recently learned that his brother was gay, asked his brother to tell him everything about his new love -- the man for whom he was moving to Australia.

Not long ago, giving Scott's ashes to the chilly wind atop Europe's legendary precipice, Steve Johnson called out four words:

"We love you, Scott."

Johnson asks anyone who may have information about his brother's death, which has been officially reclassified as an "unsolved homicide," to email justiceforscottjohnson@gmail.com.

Left: Scott Johnson

Left: Scott Johnson