This year has been a complicated one for corporate America's equality efforts. In February the Winter Olympics in Sochi forced many companies into the awkward position of condemning Russia's LGBT crackdown while still honoring multimillion-dollar sponsorships. It was a dilemma few corporations negotiated gracefully. Coca-Cola and McDonald's, for example, suffered a global backlash that saw activists hijack and subvert their marketing campaigns.

In June, Burger King introduced the Proud Whopper at San Francisco Pride. With its beguiling name and distinctive rainbow wrapper, the hamburger invited customers to expect something unique. In fact, it was the same old sandwich dressed in a custom package printed with the slogan we are all the same inside. Burger King's accompanying promotional video, filmed on location in San Francisco, immediately went viral, garnering more than 5 million hits on YouTube along with ubiquitous media coverage.

Responses to the video offer a kind of heat map of how America perceives such cause marketing. Andrew Isen, president of the Washington, D.C.-based WinMark Concepts, told The Washington Post, "They [Burger King] made a decision to connect to the gay community in a way that no other company in their category or industry has done." Other observers were less impressed. Riese Bernard, editor in chief of Autostraddle, wrote, "Eating fast food is inherently not progressive regardless of the company's positive or negative feelings about the LGBTQ community."

The problem isn't just private companies jumping on the equality bandwagon, which, in itself, can still pay dividends. It's when those same companies endorse equality without ensuring their own HR policies are inclusive. Burger King, for example, scored 55 on the Corporate Equality Index, the national benchmark for LGBT workplace policy. In the words of the Human Rights Campaign, which administers the CEI, "It's a score that reflects, among other things, a lack of employment protections on the basis of gender identity, as well as a lack of base-level health care coverage for transgender employees."

Christopher Zara, a journalist with International Business Times, is sensitive to the dichotomy underlying so-called "pinkwashing" maneuvers. "It's good that companies like Burger King are getting on the right side of these social issues. They should definitely be applauded for that," he tells me, "but we can't lose sight of the fact that this is a company that really exists to sell hamburgers. They picked up on a marketing scheme that worked in the past, recently with General Mills and Cheerios. They really wanted to have this viral social media moment, and they orchestrated it in that way. People just went with it."

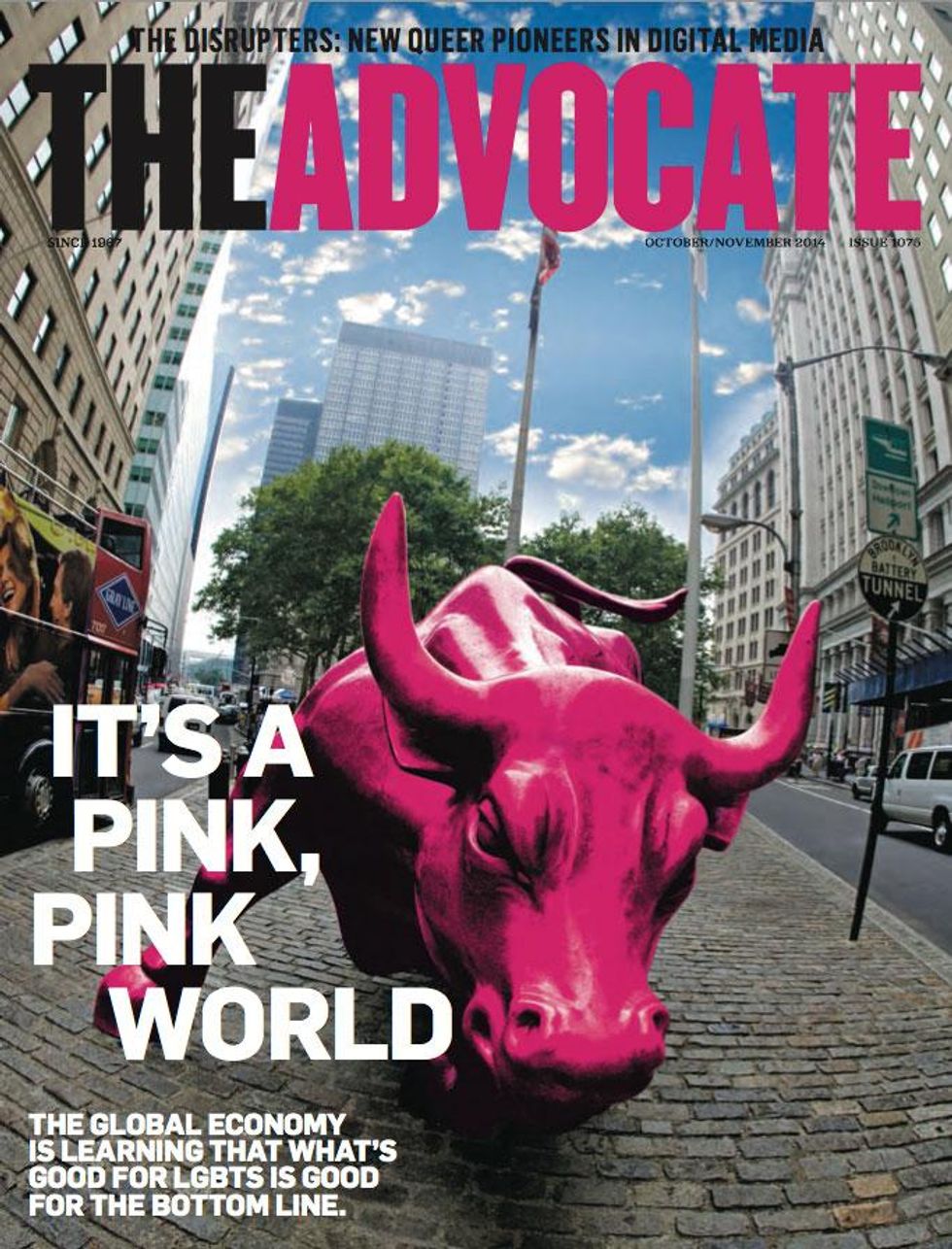

But how long can major corporations take refuge in trendy marketing? President Obama's July 21 executive order will prohibit federal employers and contractors from discriminating against LGBT employees in their hiring, firing, and relational practices. Many activists are hopeful that a fully inclusive ENDA is on the horizon and, beyond that, protection for all LGBT employees across the public and private sectors. In addition, consumers are increasingly adept at corporate reconnoitering. A 2009 report from the Council for Global Equality found that 24% of LGBT adults switched products or service providers in a 12-month period in favor of companies that support the LGBT community. According to Business Insider, LGBT spending power is estimated at more than $800 billion annually -- a still largely untapped demographic that companies are keen to start tapping.

As the Sochi Olympics demonstrated, however, even the most progressive companies are often hard-pressed to implement equality policies that are global and entrenched. (Several of the Olympics' worldwide partners scored a perfect 100 on the CEI, a fact that didn't deter them from sponsoring the games in Russia.) And as Burger King's Proud Whopper proved, allying with LGBT consumers is no longer enough to foster unconditional goodwill, let alone brand equity. Companies now need strategies that are more sustainable, more systemic, and -- not least of all -- more far-reaching.

THE QUIET AMERICANS

THE QUIET AMERICANSThe Global Equality Fund, launched by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in December 2011, is one way American multinationals are executing equality programs at scale. The fund is administered by the U.S. Department of State but isn't an exclusively American project. Nine like-minded governments -- including those of Norway, the Netherlands, and France -- are partners, along with three corporations. Among the latter are the Royal Bank of Canada, Deloitte, and the MAC AIDS Fund, the philanthropic arm of MAC Cosmetics. The primary requirement to partner is providing monetary or in-kind contributions.

The fund's mission statement is straightforward: "The Global Equality Fund is a multi-million dollar public-private fund supporting civil society's efforts to advance and protect the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) persons around the world." What this means in practice is that the fund oversees three ongoing programs: small grants, which, under the auspices of U.S. embassies and consulates, are awarded directly to civil society organizations; emergency protection, which provides emergency and preventive assistance to activists and civil society organizations under threat; and technical assistance, which supplies technology to civil society organizations.

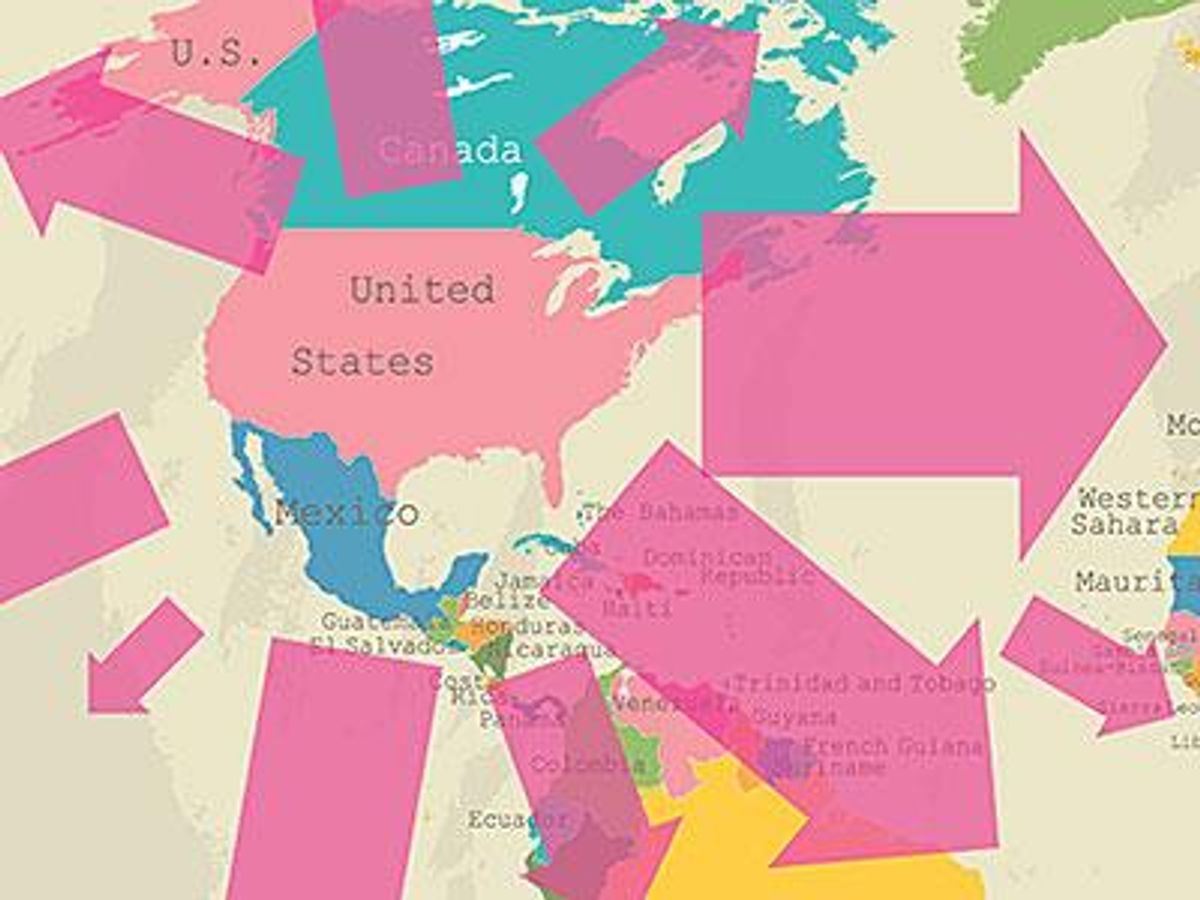

To varying degrees, each of these programs operates under a veil of secrecy. Diplomacy dictates that neither the U.S. government nor its partner corporations be implicated in supporting LGBT advocacy abroad, particularly in combustible regions such as Uganda, Nigeria, and Russia. Jesse Bernstein, a program officer in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, describes how the fund introduces accountability to those hot spots: "One of the big issues in the LGBT human rights sphere is that while everyone knows that LGBT people may be vulnerable, there's a lack of a record, so one of our priorities is making sure advocates on the ground have the resources and skills and the capacity they need to document what's happening and then share this documentation in courtrooms, with their governments, and with the international community."

Monitoring the safety of international activists is an even more urgent priority, and one the State Department is reluctant to discuss in detail. "A lot of our work is very sensitive, so I will be purposefully general," Bernstein says. "If an activist is facing harm or abuse or discrimination because of the work they're doing to advance LGBT rights -- or if someone is arrested and immediately needs a lawyer -- there's funding to provide that. If an activist also needs to relocate because the country they're in is getting too hot, there's funding for emergency relocation. Also, if a new law that undermines or is directed at LGBT persons is proposed or passed in a specific country, activists can receive a fund to mount a campaign or to fly to Geneva to present to the [United Nations] Human Rights Council."

When I ask for a specific case study of how the State Department has engineered LGBT advocacy abroad, there is a long pause. Scott Busby, deputy assistant secretary of the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, finally responds that PFLAG chapters have been established in various regions. "It's very situation-specific," he says. "Sometimes we speak out and we want companies to speak out. In a lot of circumstances, though, it involves quiet diplomacy. Quiet conversations between us and the host government, between companies and the host government."

Can American companies succeed in persuading foreign governments to reform anti-LGBT laws? And perhaps more relevant for U.S. stakeholders, do these companies protect their own LGBT employees working in unfriendly regions? Busby sums up the fund's perspective: "If an employee here in the United States gets transferred to a country where LGBT rights may be at risk, we believe it's in a company's interest -- indeed, it's a company's responsibility -- to protect that person when that person goes overseas. To that end, it's a business argument in terms of retaining talent. We also think there's a case to be made in terms of maintaining brand. A lot of people out there in the world care about whether or not companies are living by and respecting human rights in the work that they do."

Corporate America has an extensive physical presence on foreign soil. HRC reports that 64% of businesses surveyed in the 2014 CEI have operations outside of the U.S. Among those, 85% say that their nondiscrimination policies apply across all of their global operations, while 54% have distinct global codes of conduct that specify workplace inclusion standards regarding sexual orientation and gender identity. Overall, when it comes to verifying that third-party suppliers and contractors share their values, 61% of American companies claim to conduct such audits.

When asked if the fund has specific guidelines for LGBT Americans working overseas, Busby says that's beyond the scope of the Global Equality Fund. The U.S. government offers such recommendations in the form of literature or talking points rather than actionable programs. Or if such programs exist, Busby doesn't mention them.

This isn't surprising. The United States hasn't achieved unanimity in its own nondiscrimination laws, President Obama's executive order notwithstanding. When I ask Busby if mixed signals in the U.S. undermine equality efforts abroad, he says, "Our view is that there is a global consensus -- or close to a world consensus -- that LGBT persons should not be subject to violence or discrimination. Yes, there are ongoing challenges in the United States, and there are disagreements around some issues, but we think if we're focused on issues of violence and discrimination, there's a broader consensus."

"BUSINESS IS SOMETHING THAT EVERYBODY UNDERSTANDS"

"BUSINESS IS SOMETHING THAT EVERYBODY UNDERSTANDS"For Todd Sears, founder of Out Leadership, consensus around human rights is secondary. His organization connects senior executives from law, insurance, and finance in order to leverage the collective reach of those industries. "I primarily focus on the business sustainability and the business bottom line impact," he tells me. "I call it 'return on equality.' "

The idea is simple: When companies enforce LGBT-inclusive policies, they acquire and retain talent, foster a more collaborative workplace, and curry the favor of socially conscious consumers. "I know that people actually are now paying attention to LGBT-friendly policies or LGBT-unfriendly policies," Sears says. "If you look at Chick-fil-A and [the company's CEO] Dan Cathy's homophobic comments, the [YouGov] BrandIndex of Chick-fil-A dropped sharply. If it were just gay people driving that BrandIndex down, that would not have happened."

Out Leadership partners with the Global Equality Fund, mostly as a means for its member firms to operate internationally without incurring "reputational risks." When companies enter a foreign market that doesn't support LGBT rights, Out Leadership provides business briefs that describe the country's discriminatory laws and why they're bad for business. Also included are the names of 15 influencers in the country and five to seven talking points that American executives can relay. "It's literally turning our senior business leaders into advocates, but doing it in a business context," Sears says. "We're not giving them placards; we're not doing protests. We're really educating them so that when they're in these business meetings, they can make comments and actually drive conversation from a business perspective."

When I ask why a business-first conversation is more effective than one about human rights or culture or religion, Sears says, "It's a universal driver. Lots of things don't translate. Cultures are different. Pop stars may be popular one place but not others. Movies can be popular one place but not others. But business is something that everybody understands, and commerce is something that every country needs."

Even if commerce -- and, by proxy, money -- is a universal language, that doesn't mean it affects every industry in the same way. The Global Equality Fund doesn't offer sector-specific strategies, nor does Out Leadership. "I'm very focused on not expanding too far too quickly," Sears tells me. "I do want to make sure we're providing value and ROI [return on investment] to our members, and that we're growing in a very sustainable and smart way. We could easily create a vertical for manufacturing, a vertical for industrials, for hospitality, for pharmaceuticals, for media -- the list goes on."

Indeed, manufacturing, mining, and oil and gas companies are among the least progressive industries for LGBT inclusion. Exxon Mobil, for example, scored -25 on the CEI, the sole negative rating on the index. Although the company has stated it will abide by the president's executive order, as of press time it remains unclear whether that will hold true. When other multinational energy corporations were asked for comment, only Valero and Halliburton responded. Both earned CEI scores of 15 (based on public records since they declined to report their policies to HRC). Halliburton offers benefits to employees and their legal spouses, which include domestic partners, in states that recognize them. Valero extends health care and other benefits to same-sex domestic partners. Asked if they also vet third-party suppliers and vendors for LGBT-friendly policies, Valero did not reply, and Halliburton issued a noncommittal memo: "[We recognize] the importance of utilizing local, small, and diverse business enterprises that offer quality products and services on a competitive basis and see[k] to provide the maximum opportunity for their participation in our procurement and sourcing processes."

THE IMPERIALISTS

"I'd love to meet with Exxon Mobil and talk to them about how they can be better. If they really want to keep their government contracts and be on the right side of history, this is an excellent opportunity for them to look at things," Thom Lynch says. As chief development officer at Out and Equal Workplace Advocates, he understands better than most how a company's HR policies can sway its stock, PR, and brand index.

For Exxon Mobil, the stakes are especially high. The Texas-based giant won more than $480 million in primary federal contracts in 2013 (and has won $6.6 billion since 2005). Valero won more than $672 million in federal contracts last year. KBR, a former subsidiary of Halliburton that was spun off in 2007, won more than $39.5 billion in federal contracts between 2003 and 2013, many of them sweetheart deals stemming from the Iraq War.

"I'm curious to see what kind of impact the president's executive order has for those kinds of contracts," Lynch says. "I know there will be a ramp-up time, and it'll be interesting to see how the government deals with companies that are not in a good position."

Also interesting is the potentially lucrative opportunity for organizations to help rehabilitate corporate offenders. As the U.S. seeks to standardize antidiscrimination and equality laws, companies will need clear guidelines and best practices. This is even more critical as firms expand overseas. But as Lynch points out, there's danger in thinking that America's equality protocol can be exported wholesale: "It's very easy from the outside to say 'make a policy,' but you may be risking people's lives." Out and Equal connects corporations to local NGOs for the purpose of facilitating roundtable discussions about how each can put quiet pressure on host governments. "The last thing we want is to be an American organization that goes into a foreign country and tells them what to do," Lynch says.

The charge of cultural imperialism is one echoed by Uganda's president, Yoweri Museveni. In December 2013, Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Group, posted this message on his company's Web site: "Governments must realize that people should be able to love whoever they want. It is not for any government (or anyone else) to ever make any judgments on people's sexuality. They should instead celebrate when people build loving relationships that strengthen society, no matter who they are." Specifically citing Uganda, he urged companies and tourists worldwide to take their business elsewhere.

There's no denying that the scrimmage between cultural values and commerce will ultimately determine whether corporate America can effect equality legislation abroad. The implicit ultimatum is either choose the Branson method -- punishment by sanction -- or the Global Equality Fund's method of strategic investment. Either way, Thom Lynch sees a burden on corporations to take the lead. "Policies at many of our corporations are more expansive than what government policy is," he says. "It's corporations that are pressuring government to have a national law on marriage, a national law on nondiscrimination. A lot of these companies know that history is heading in one direction, and they want to be a part of it."

The idea of being on the right side of history is integral to the LGBT movement. Christopher Zara sees that as a direct inheritance from the civil rights movement, with the difference that now the movement is global, commodified, and underwritten by massive advertising dollars. If equality is to spread across the U.S. and migrate abroad, Middle America will be at least partly responsible for lending it legitimacy. "When you see a marketing campaign that's geared towards a social cause from a private company that exists to sell hamburgers or cereal or whatever, you always have to be a little skeptical," Zara says. He compares equality campaigns to the pink ribbons used to raise breast cancer awareness. "That's a very successful campaign, but it's come under a lot of criticism from advocates who say it's being subverted by companies that take much of the profits and put them into their own pockets. As consumers, we should strive to be more aware of what's behind the campaign and the motivation behind it." Which, theoretically, would make the cause itself more authentic.

For Todd Sears of Out Leadership, global standards of equality are a matter of making LGBT acceptance a nonnegotiable part of foreign governments' infrastructure. He likens equality to building codes: "It's good for safety to have OSHA regulations, right? If a company is going to build a new headquarters in India, they want to make sure the government actually has regulations on the building because businesses care about the safety of their employees and the longevity of their business. It's no different -- just as you had to have building codes up to speed, you have to have LGBT inclusion up to speed." This also implies that American corporations must be prepared to invest heavily in communities abroad. And because the tide of history is inexorable and uprooting, these companies must also be prepared to weather some storms.

THE QUIET AMERICANS

THE QUIET AMERICANS "BUSINESS IS SOMETHING THAT EVERYBODY UNDERSTANDS"

"BUSINESS IS SOMETHING THAT EVERYBODY UNDERSTANDS" Also interesting is the potentially lucrative opportunity for organizations to help rehabilitate corporate offenders. As the U.S. seeks to standardize antidiscrimination and equality laws, companies will need clear guidelines and best practices. This is even more critical as firms expand overseas. But as Lynch points out, there's danger in thinking that America's equality protocol can be exported wholesale: "It's very easy from the outside to say 'make a policy,' but you may be risking people's lives." Out and Equal connects corporations to local NGOs for the purpose of facilitating roundtable discussions about how each can put quiet pressure on host governments. "The last thing we want is to be an American organization that goes into a foreign country and tells them what to do," Lynch says.

Also interesting is the potentially lucrative opportunity for organizations to help rehabilitate corporate offenders. As the U.S. seeks to standardize antidiscrimination and equality laws, companies will need clear guidelines and best practices. This is even more critical as firms expand overseas. But as Lynch points out, there's danger in thinking that America's equality protocol can be exported wholesale: "It's very easy from the outside to say 'make a policy,' but you may be risking people's lives." Out and Equal connects corporations to local NGOs for the purpose of facilitating roundtable discussions about how each can put quiet pressure on host governments. "The last thing we want is to be an American organization that goes into a foreign country and tells them what to do," Lynch says.