Homophobia thrives in most countries in Africa, making the continent an oppressive place to live for countless LGBT people.

November 17 2014 5:00 AM EST

May 26 2023 2:12 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Homophobia thrives in most countries in Africa, making the continent an oppressive place to live for countless LGBT people.

Months after Uganda's Constitutional Court overturned its Anti-Homosexuality Act, which prescribed life in prison for many instances of gay sex, nearly identical legislation returned -- this time in the Gambia.

In October, Chad took up a sweeping bill that calls for 20-year prison sentences for those percieved to be LGBT.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to institutionalized hatred for lesbians, gays, bisexual, and transgender people in Africa.

Human rights groups are demanding that Chadian president Idriss Deby scrap plans to enact a draconian antigay law that would jail people for up to 20 years because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

"If this homophobic bill becomes law, President Deby will be blatantly disregarding the country's international and regional human rights obligations," said Salil Shetty, Amnesty International's secretary-general, in a statement last month. "He will deny people their right to privacy, will institutionalize discrimination and enable the stigmatization, harassment and policing of people who are, or are perceived to be, gay -- regardless of their sexual behavior."

Amnesty reports the Chadian penal code, approved in September by the country's executive cabinet, proposes the criminalization of same-sex sexual conduct, suggesting 15- to 20-year jail sentences and fines up to $1,000 for those found "guilty." Amnesty warns that the bill is so broadly written that it could see citizens jailed for unsubstantiated rumors, or for simply failing to adhere to societal gender norms. The bill now sits before Chad's parliament, which may well approve the legislation.

Learning (or not) From Uganda

Apparently, the Chadian government didn't get the memo about the international and financial impact Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Act had on that nation during the six months it was in force, before being overturned on a technicality in August by the Constitutional Court in the capital city of Kampala.

After Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni signed the act into law in February, the east African nation became the target of international criticism and saw nearly $200 million in aid donations from Europe and North America vanish. Gone in a matter of weeks were substantial portions of government aid contributions from Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Holland, and by March, the U.S., which also canceled a scheduled military exercise between U.S. and Ugandan armed forces. By summer's end, the White House announced that it would deny visas to certain Ugandan officials, that it was scuttling plans for an HIV and AIDS research program at a Ugandan university, and that the country would no longer be the location for a planned $3 million health institute in east Africa.

The Constitutional Court, which threw out the law on grounds that it was not passed by a proper quorum in the Ugandan Parliament, is seen by some as fairly independent from the country's dictatorial president, who has ruled Uganda since 1986. Other observers speculated that Museveni himself arranged for the court ruling striking down the law.

More Machiavellian analysts believe Museveni withered under the pressure of losing much of the foreign money that helps prop up his government. Those analysts further warn that the suspension of Uganda's antigay law -- by the purported whims of a dictator or on a procedural technicality by the Constitutional Court -- at best provides only temporary, partial relief to LGBT people in Uganda.

Human rights activists familiar with the situation for LGBT Ugandans say Museveni could just as easily help shepherd in and sign a new, perhaps even harsher, antigay law. Activists worry that the dictator may indeed take that route to whip up popular support for his next presidential bid in 2016, as an overwhelming majority of Ugandans supported the draconian law.

Although U.S. measures against Uganda's antigay law may not always have been tailor-made to fit suggestions from international LGBT and human rights groups, the Obama administration was far from unresponsive during the the act's time in force. To the contrary, in the final analysis, U.S. pressure may have been optimal in terms of achieving the desired effect of encouraging Uganda to ditch the law.

Now, however, with a foreign policy portfolio bulging at the seams and antigay legislation on the African continent looking more like a potential back-burner issue, those same human rights groups aren't taking any chances. Groups such as Amnesty International and Washington, D.C.-based Human Rights First are urging the president and the State Department to use the Uganda experience to similar effect in Chad.

"Following the U.S.-Africa Summit in August, where President Obama met with African heads of State to discuss strengthening economic and democratic ties between the United States and Africa, it is time that the United States make clear that the future of these bilateral relationships will be damaged by the enactment of antigay legislation," says HRF's advocacy counsel for LGBT rights, Shawn Gaylord. "We hope that the State Department will respond deliberately, as it did when Uganda passed its antigay law, with a plan to respond to the passage of these bills."

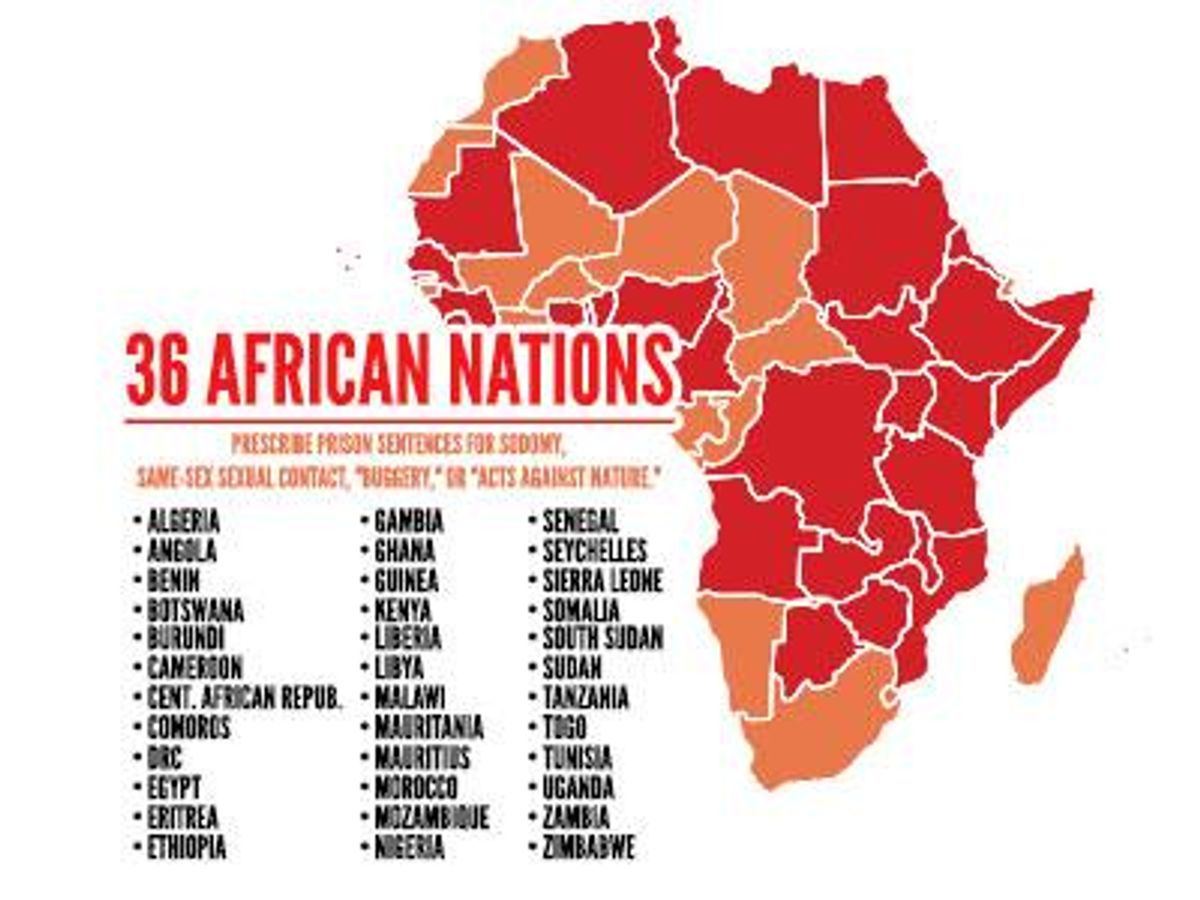

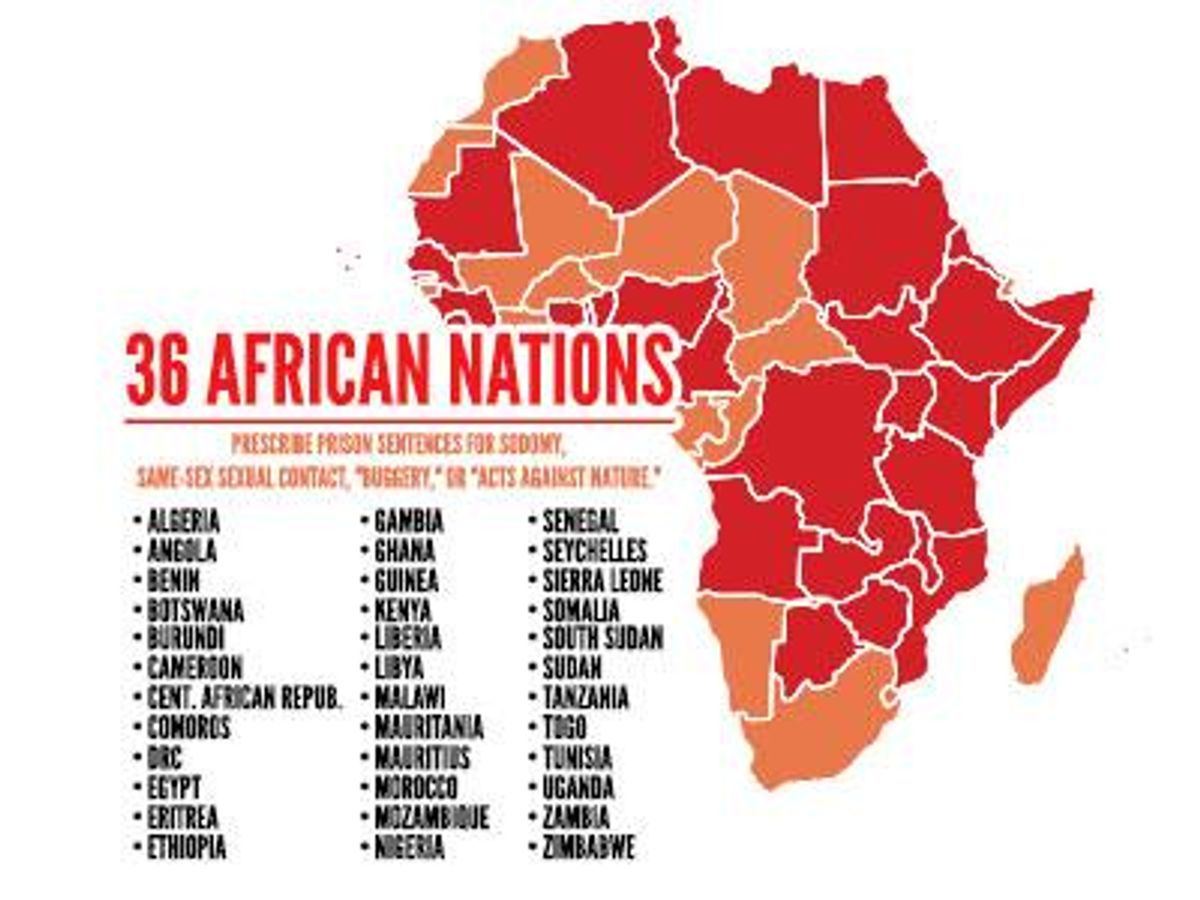

While Uganda and Chad have recently found themselves in the limelight of the international community's efforts to stamp out homophobia, a partial look around the continent reveals that Africa is an especially tough place to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender-nonconforming, or queer.

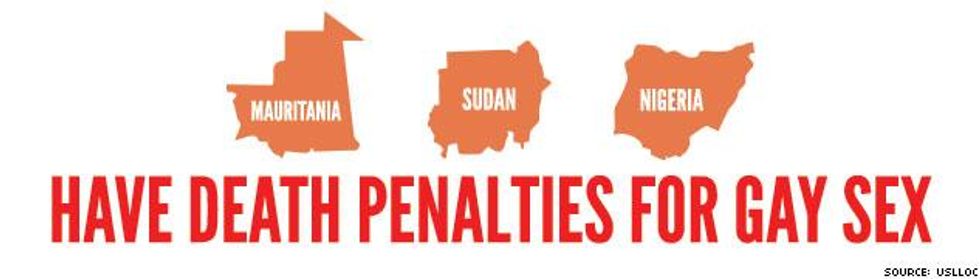

Four African nations expressly call for capital punishment for those convicted of same-sex sexual contact, often labeled a "crime against nature," "sodomy," or, in a nod to the colonial origins of such harsh antigay laws, "buggery." Those nations are Mauritania, Sudan, Somalia, and Nigeria.

In Nigeria and Sudan, those who are convicted of being gay but spared death are subjected to public lashings. And while Sudan is the only African nation that prescribes a specific number of lashes for the "crime" of being LGBT, Nigeria has the dubious distinction of being the only African country to expressly ban the "promotion" of homosexuality.

A staggering 32 countries in Africa criminalize same-sex sexual contact with jail time: Algeria, Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Malawi, Mauritania, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Among those, four countries call for lifelong prison sentences for those "convicted" of what is often labeled "aggravated homosexuality." Those nations are Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zambia, and most recently, The Gambia.

Nations that sentence convicted LGBT people to hard labor include Angola, Mauritius, Morocco, and Mozambique.

In Cameroon the penal code effectively makes homosexuality illegal, and in 2013 the country arrested more LGBT people than any other nation in the world. The deeply traditional and often superstitious culture extends to public officials, including a police officer who, after arresting seven reportedly "effeminate homosexuals," told the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS that gays and lesbians are "people who are controlled by an evil spirit." A Cameroonian attorney who represents LGBT clients recently revealed that judges in the central African nation rely heavily on stereotypes when determining if a suspect is gay. In fact, a suspect who has allegedly drunk Bailey's liqueur can see that information admitted as evidence of their homosexuality.

Even in countries where being gay is not expressly forbidden, LGBT people often face an existence filled with state-sanctioned harassment and assault.

Despite the fact that it was seen as a safer haven from Uganda for LGBT people during the reign of fear that followed the enforcement of the now-defunct Anti-Homosexuality Act, homophobia and transphobia are on the rise in neighboring Kenya. Earlier this year, 60 people were arrested at a nightclub in Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, for "alleged homosexuality."

Being gay is not illegal in the Democratic Republic of Congo. However, LGBT people are routinely persecuted by society and even members of their own family, often finding themselves prosecuted under indecency laws. Earlier this year, a British citizen went through a harrowing ordeal involving her Cameroonian family, who confiscated her passport as they tried to "cure" her of being a lesbian, reported U.K. newspaper The Independent. As the British citizen attempted to leave the British Embassy in Kinshasa after attempting to obtain an emergency passport, police arrested the Briton, who grew up in England after emigrating from Cameroon as a toddler.

Because of its close proximity to Europe and its image as a relatively tolerant Muslim society, Morocco has long been a popular tourist destination with Westerners of all stripes -- including gay travelers. However, Morocco is now feeling the economic pinch of a steep drop in the tourism trade brought on by media exposure of an ISIS beheading in next-door Algeria as well as the arrest of 70-year-old British citizen, Ray Cole. Cole was held for 19 days in a Moroccan prison he likened to a concentration camp for an alleged gay encounter.

Even in Equatorial Guinea, where gay sex is technically not illegal, four youths were recently forced by police to explain themselves for allegedly having gay sex. The police interviews were broadcast on national television.

One bright spot on the continent is South Africa, the only country with specific protections against discrimination aimed at LGBT citizens. South Africa is also the only nation in Africa with marriage equality. Earlier this year, South Africa welcomed its first openly gay member of Parliament, Zakhele Mbhele.

But even in South Africa, there are those who can't hide their homophobia. In fact, President Jacob Zuma once said that allowing gay people to marry or adopt children would be "a disgrace" to South Africa and to God.

And while a recent win for LGBT activists in Botswana -- who earned the right to formally register their advocacy group with the state after petitioning the country's Supreme Court -- was a major victory, it comes in a nation that still criminalizes being LGBT with seven-year jail sentences.

How to Help

There are currently two bills before the U.S. Congress that aim to prioritize the protection of LGBT people worldwide as a key facet of U.S. foreign policy initiatives, explains HRF's Gaylord.

"The International Human Rights Defense Act would establish a Special Envoy on LGBT rights in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor of the State Department, ensuring global LGBT rights remain a key foreign policy priority," Gaylord tells The Advocate. "The Global Respect Act would ban foreigners who have committed or incited basic human rights violations against LGBT individuals from entering the United States."

Human Rights First recommends three ways for Americans who care about LGBT equality to pressure the government to act against homophobia in Africa:

"American LGBT people and allies can call their congressmen, congresswomen, and senators and ask them to support these two important pieces of legislation," Gaylord says. "There is also a petition online sponsored by the American Jewish World Service that asks President Obama to appoint a Special Envoy on Global LGBT Rights."

Finally, says Gaylord, "local human rights groups and LGBT community groups in Africa are always in need of additional support from the international community. People can reach out to them directly to find out the best ways to become involved."