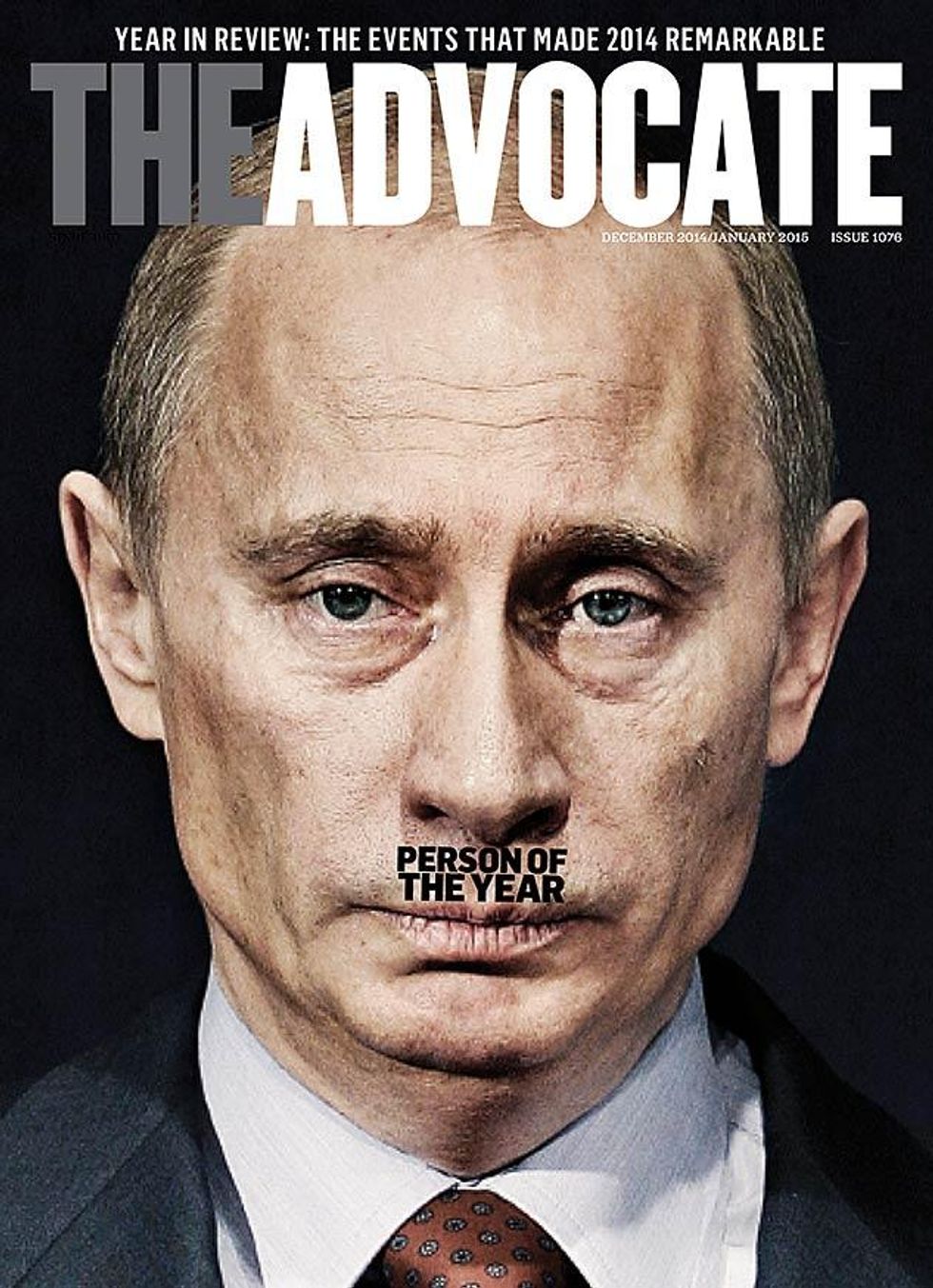

"Imagine a boy who dreams of being a KGB officer

when everyone else wants to be a cosmonaut."

This quote appears early in The Man Without a Face, Masha Gessen's 2012 biography of Vladimir Putin. It's as succinct and illuminating a characterization of the Russian president as you're likely to find. The KGB, after all, perfected the thuggery, espionage, and aimless bureaucracy that are hallmarks of Putin's regime. The agency's crackdown on dissidents offered a blueprint for Putin's own strongman excesses. That he aspired to such a career as a child tells us something useful about his psychopathology: This is a man hardwired to intimidate.

Nowhere is this tendency more apparent than in his crusade against LGBT Russians. Since winning a third term in 2012, Putin has become ever more autocratic, and his antigay ideology ever more extreme. In June 2013, he signed the infamous antigay propaganda bill that criminalizes the "distribution of information...aimed at the formation among minors of nontraditional sexual attitudes," with nontraditional meaning anything other than heterosexual. Individual violators are fined anywhere between $120 and $150, while NGOs and corporations can incur fines as high as $30,000. International outrage flared in the months before the Sochi Olympics, in response to which Putin reassured the gay and lesbian community they had nothing to fear as long as they left Russia's children in peace.

Such incendiary rhetoric is a staple of Putin's political playbook. And in Russia, where the majority of media are state-owned, there's little public pushback. Tanya Cooper, a researcher with Human Rights Watch, argues that the average Russian is unlikely to seek diverse viewpoints. "When politicians, celebrities, and respectable journalists in Russia tell you repeatedly, either on television or in print, that gay people are perverts, sodomites, and pedophiles, you just believe it," she says.

According to Pew Research's 2014 Global Attitudes Project, 72% of Russians think homosexuality is morally unacceptable. This hints at the increasing domination of the Russian Orthodox Church, which between 1991 and 2008 saw the number of adults calling themselves adherents increase from 31% to 72%. In July 2013, Patriarch Kirill I, leader of the church, deemed same-sex marriage "a very dangerous sign of the apocalypse," a sentiment that appeals to Putin's conservative base. Julie Dorf, a senior adviser at the Council for Global Equality, argues that Putin relies on the church to legitimize his rhetoric, and in turn, the church gets greater political access. "Without [Putin's] personal agenda of using homophobia as a tool to keep himself buoyed domestically, I don't think the church's own homophobia would have risen to the same level," Dorf says.

(RELATED: See The 9 Other Finalists for Person of the Year)

A September 2014 poll from Russia's state-run Public Opinion Foundation found that of the two-thirds of respondents who said celebrities can be moral authorities, 36% cited Putin, putting him far ahead of Patriarch Kirill I, who was cited by just 1%. Indeed, Putin's statecraft and overarching political vision have become staunchly Manichaean, as a struggle between diametrically opposed forces. As Mark Galeotti and Andrew S. Bowen wrote in Foreign Policy, "He does not see himself as aggressively expanding an empire so much as defending a civilization against the 'chaotic darkness' that will ensue if he allows Russia to be politically encircled abroad and culturally colonized by Western values at home." Framed like this, Russia's assault on LGBT rights is really just opposition to American hubris.

"I'm not sure he's a particularly moral person," Dorf says. "My sense is that the political power he's getting from the antigay campaign is less about being morally right than about defining Russia as 'not the West.' "

Cooper agrees, and sees Russia's anti-LGBT dragnet as the most appalling example of a broader rejection of foreign subversion. "The attack on the LGBT community in Russia started almost simultaneously with the attack on civil society and the demonizing of NGOs as foreign agents," she says. "There was a campaign to expose all the evils of Western culture and say that immigrants, liberals who get their inspiration from Western political culture, and LGBT people are all Western exports and therefore alien to Russia."

The notion of Russian purity is the cornerstone of Putin's identity, underlying everything from photo ops to the annexation of Crimea. On his personal Web site, administered by the Russian Presidential Executive Office, we learn that "Putin prefers Russian cars," is "particularly fond of fishing in Russia," and as chairman of the Russian Geographical Society's Board of Trustees, is devoted to "[inspiring] people to love Russia." His 2012 state-of-the-federation address framed his nationalist fervor as a social awakening: "In order to revive national consciousness, we need to link historical eras and get back to understanding the simple truth that Russia did not begin in 1917, or even in 1991, but rather, that we have a common, continuous history spanning over 1,000 years and we must rely on it to find inner strength and purpose in our national development."

That LGBT Russians have no place in this development is simply a hard demographic truth. In 2013, Russia's birth rate exceeded its death rate for the first time in two decades -- a trend Putin is keen to sustain. In language disturbingly reminiscent of Nazi propaganda, he told reporters in January that anything that gets in the way of Russia's population growth should be "cleaned up." In addition to LGBT undesirables, Russia's ethnic minorities also pose a threat, as do freethinkers who openly critique the regime. In a survey of the past two decades by the Committee to Protect Journalists, Russia was ranked the fifth most dangerous country for reporters, with at least 56 killed between 1992 and 2003; the International Federation of Journalists estimates the number is even higher. The message is clear: Putin's Russia, in grand Soviet tradition, is a country of the masses, not the individual.

Yet it's the masses that must safeguard individual liberties. The Sochi Olympics catalyzed an intense campaign for reform -- there were widespread calls to boycott the games; President Obama criticized Russia's LGBT policies; a Change.org petition urging Olympic sponsors to condemn the anti-LGBT laws garnered more than 225,000 signatures -- but nothing really changed. "After Sochi ended, attention shifted somewhere else," Cooper says. When asked if there have been any positive developments for Russia's LGBT community since February, she answers simply, "No."

Recent headlines offer little to celebrate. On August 28, agents from Russia's Federal Security Service ransacked the home of Andrei Marchenko, a blogger whom they accused of masterminding a "gay terrorist underworld." On September 18, Queerfest, an annual LGBT rights festival in St. Petersburg, canceled most of its events after bomb threats and attacks that saw antigay protesters squirt festivalgoers with an unknown gas and green dye. On September 25, the Constitutional Court of Russia upheld the antigay propaganda law. And of course LGBT Russians continue to be assaulted or murdered with tragic frequency. On September 7, Yekaterina Khomenko, a 29-year-old lesbian who taught tango lessons to same-sex couples in St. Petersburg, was found dead in her car, a four-inch slash across her throat. Police initially called her death a suicide.

"Putin's not going away until 2024, so the situation, politically, isn't going to change for quite some time," Dorf says. The prospect of another decade under Putin is devastating. Despite encouraging developments such as the International Olympic Committee's new mandate requiring prospective host cities to sign an antidiscrimination clause, Russia's LGBT activists report few breakthroughs. What hope they have is precarious and underground. Their enemy is an eternal KGB agent with dreams of empire, a pragmatist and sportsman who crushes his opposition while still incongruously proclaiming, as he did in a New York Times op-ed, "[We] are all different, but when we ask for the Lord's blessings, we must not forget that God created us equal."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes