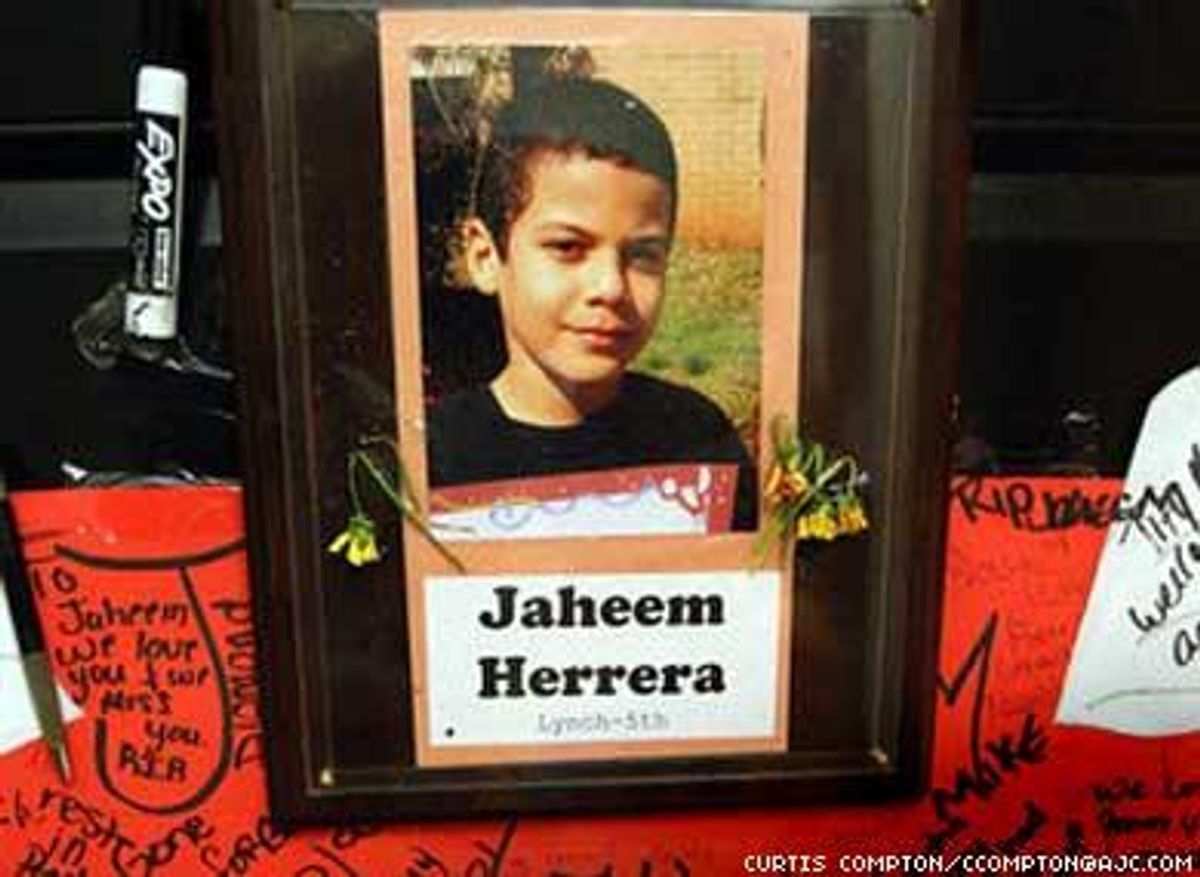

Jaheem Herrera woke up on the morning of April 16 with a knot in his stomach. Over Cocoa Puffs, the 11-year-old told his mother, Masika Bermudez, that he didn't want to go to school, but he seemed more reluctant than sick. He slammed the door on his way out of the family's Decatur, Ga., apartment.

At lunch the knot tightened and swelled so much that he wouldn't eat. He was quiet and in a terrible mood -- a silent anger mixed with fear. His classmates at Dunaire Elementary School often taunted him in the cafeteria. To them, he was gay, a fag, a mama's boy, and a virgin because he had recently moved to Georgia from the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to attorney Gerald Griggs, who now represents the family.

Later he heard someone tease him again and asked his best friend, A.J. Brown, if anyone would miss him if he were to leave. Brown said that he would, and when the final bell of the day sounded, Herrera said "bye" as he climbed into his mother's boyfriend's car. At home Herrera was so frustrated that he could only yell. He was sent to his room to cool off before dinner, but his stomach was already filled. He locked the door, went into the closet, found a cloth belt, and hanged himself silently.

His sister Yerralis's calls at the bedroom door went unheard. When the family finally burst into the room, she ran to claw at the belt and screamed, "Get him down. Get him down." Bermudez held his already-cold body and asked herself questions.

The family put a makeshift shrine on the front door of their two-bedroom apartment and buried him in a white casket with three gold crosses stitched inside. Since Herrera's death, a growing chorus has joined Bermudez in asking how an 11-year-old who loved dancing like Michael Jackson could find his days so afflictive that he would want to end them.

Herrera joins names like Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover, Eric Mohat, and Lee Simpson -- youths who took their own lives in response to antigay bullying. Sixty-five percent of middle and high school students surveyed by the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network report being bullied because of their perceived sexual orientation, gender expression, race, religion, and other factors, and many of them believe adults can offer no help. Walker-Hoover's mother, Sirdeaner Walker of Springfield, Mass., has called for sweeping reform of school antibullying policies across the country, and Herrera's family has joined the push.

On Tuesday, Rep. Linda Sanchez of California introduced the Safe Schools Improvement Act in the House of Representatives. It will require schools that receive funding under the Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act to implement an antibullying policy that protects students from harassment and covers sexual orientation and gender identity, among other characteristics.

GLSEN executive director Eliza Byard said her organization's research shows that schools with enumerated antibullying policies that specifically include sexual orientation see improvement over schools that take more general approaches.

"Bullying is not some kind of expectable rite of passage," Byard said. "Bullying is a public health problem. [It] is a situation in which the bully and the target need our help and need support in dealing with the consequences of the bullying or -- for the bully -- with the circumstances that lead them to behave that way."

She added that legislation is not the whole answer -- results hinge on "effective implementation, which requires concerted and prolonged effort."

Griggs said the DeKalb County, Ga., school system failed Herrera because it could not implement the antibullying policies already in place.

He said DeKalb County has a "very good" antibullying policy, but the school failed to implement to it and failed to respond to Bermudez's repeated complaints. She complained to the school seven times, but administrators did nothing even after Herrera was choked until he was unconscious in a bathroom one day, the attorney said. Police even told the school to monitor the situation more closely, he said, but little was done.

"From the investigation that we conducted, they failed every single way possible to protect these children," Griggs said.

Byard said responding to sexual bullying is a touchy subject for school employees throughout the country. She said LGBT students have reported that when staff members receive sexual bullying complaints, 80 percent do little or nothing about it.

"It's the fear of not knowing how to [help]," she said. "They may not recognize the severity of what they're witnessing. They may worry that they won't be backed up by the school administration and if they do take action, they'll be some kind of controversy about homosexuality at schools. So you have a kind of language that is a pronounced element of the problem, yet it's the kind of language that teachers are less likely to actually deal with. That's a real problem."

Dorothy Espelage, a bullying expert and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Illinois, said bullying has not increased in prevalence over the years, but the context has become more homophobic in nature. She added the increased focus on standardized test scores as a result of No Child Left Behind has drained schools of psychosocial resources, making the emotional well-being of students a lower priority.

Griggs said bullying is not the same as when he was in school.

"There was name-calling, maybe a couple of fights," he said. "Now you have people attacked in restrooms -- threats, weapons -- and the schools are sticking their heads in the sand. Now we're seeing the community stand up and say, 'Look, if you're not going to do anything, then we will. We're going to sit in the schools. We're going to go to the state legislature, and we're going to demand them to change the laws. We're going to put the spotlight on them because our kids do not need to live in an environment of terrorism when they're just trying to learn. ... It's a systemic problem that is not only here in Georgia, but in Ohio, Springfield, Mass., and Texas -- they need to look at this on the federal level."

Herrera's family said the issue is related not only to homosexuality. At 11, boys are too concerned being boys, they said.

Griggs said Herrera grew despondent when his mother's complaints were not properly received and depressed when classmates called him a "snitch" for telling his mother. He added that when Bermudez came home with no good news after complaining, Herrera didn't want to burden her further, and he had faced the bullying alone since December.

Espelage said students need a support person within the school if their complaints are to be taken seriously. With more energy and less naivete, she said, older students are at a greater risk to become school shooters. But younger students who cannot process their bullying, she said, are more likely to internalize their problems and turn on themselves.

Bermudez and Walker appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show Wednesday to make the discussion of school bullying national, hoping that what happened to their sons will never happen to another child.

Walker, who has recently appeared on Today and The Ellen DeGeneres Show, said she never asked for this spotlight. But in a recent interview with this magazine, she said she seeks change by any means necessary.

The respective school systems in Springfield, Mass., where Walker-Hoover lived, and DeKalb County have launched internal investigations. DeKalb County district attorney Gwen Keyes Fleming said her department has also started an investigation. Walker has called for a state-level probe of her son's school, aimed at determining exactly what happened, and ways to amplify the implementation of antibullying policies to prevent further tragedy.

Byard said the change doesn't stop at the schoolhouse door.

"Some of us are more focused on policy change in the school context, but it does take all the sectors of the school community to ensure that young people are safe," she said. "It also requires that all the members of the community to live the behavior that they want young people to emulate, and I think that's part of the challenge as well. We need to be part of the solution. At the point when we as adults don't live up to what we're asking young people to do, we've pretty much lost the battle."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered