"It's better to be it, and not look it, than to look like it, even if you are not it," repeats the abuela, or grandmother, of the esteemed writer Richard Blanco throughout his new memoir, The Prince of Los Cocuyos.

Back in 1970s Miami, Blanco had not yet grown to become the first gay, Latino, and immigrant inaugural poet, who helped usher in President Obama's second term with the hopeful ode to unity, "One Today."

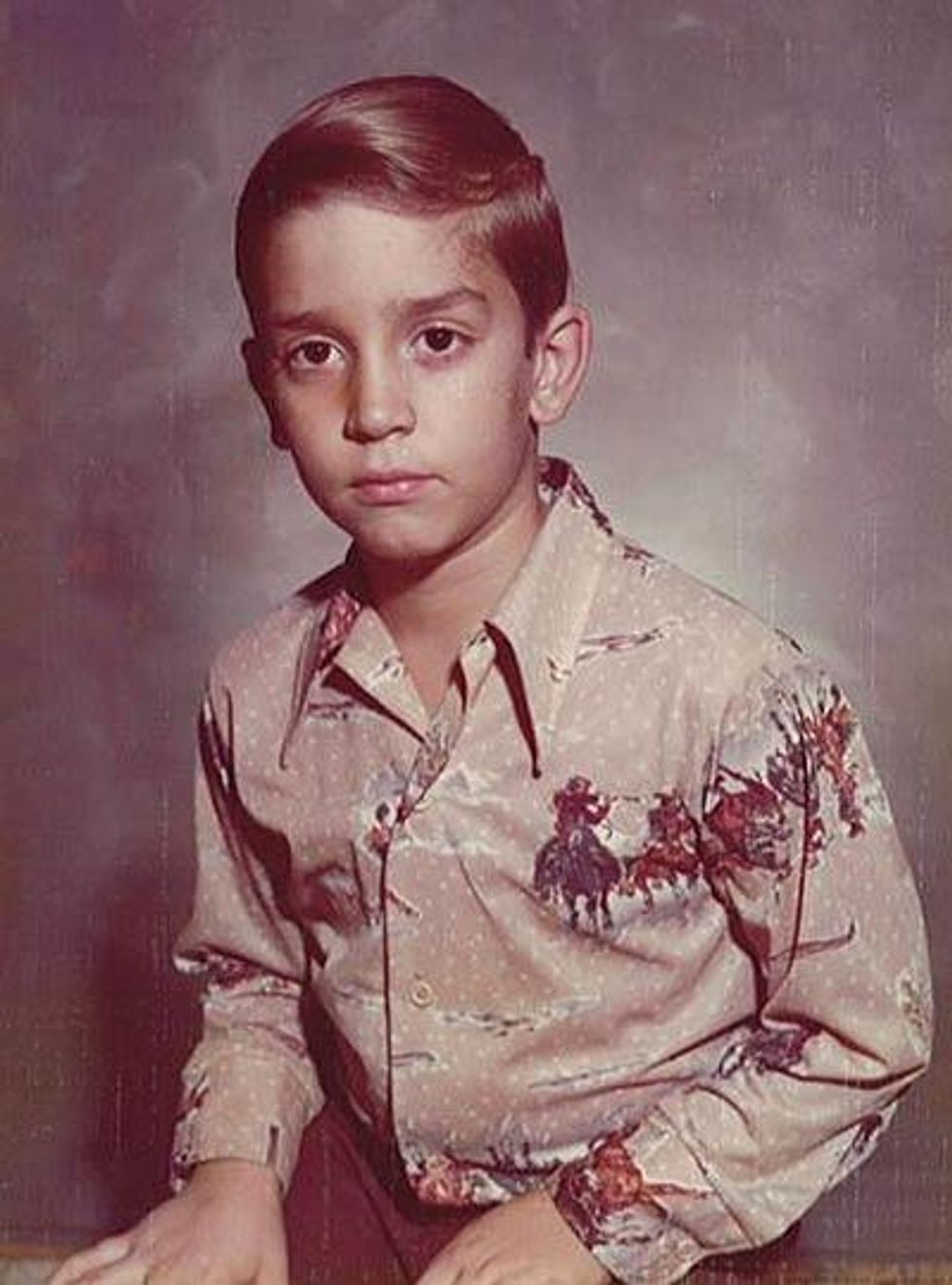

He was Ricky -- an overweight and sensitive child with creative tendencies that raised red flags to his Cuban grandmother, who saw toys like crayons or a Mickey Mouse "doll" as warning signs of what was to come. For Ricky, the term "gay" had not yet entered his vocabulary or ken. But it manifested as all the things he loved and which he was shamed for loving.

"At that age, I only understood that it meant watching telenovelas; it was my paint-by-number sets; it was my cousin's Easy-Bake Oven I wanted for my own -- all the things I enjoyed for which she constantly humiliated me," Blanco writes.

Sitting in a courtyard of an out-of-the-way Hollywood cafe, Blanco, now 46, reflects on the words of his late grandmother, who is painted in his coming-of-age book with the contrasting colors of love and exasperation reserved only for the closest of family members. In his view, her statement speaks to a code of masculinity in Latino culture and the "great irony" in its rules of perception versus reality.

"Being gay is not the crime, if you read into my grandmother. It's being effeminate," Blanco interprets. "There's a layer of machismo relevant to Latino culture, where it's about this hypermasculine society. And the irony of a hypermasculine society, like the Greeks, is it is completely homoerotic."

"Being gay is not the crime, if you read into my grandmother. It's being effeminate," Blanco interprets. "There's a layer of machismo relevant to Latino culture, where it's about this hypermasculine society. And the irony of a hypermasculine society, like the Greeks, is it is completely homoerotic."

"She knew what was coming down the pipe. And her acts were always about butching me up," he adds with a laugh, before his voice drops down to an incredulous whisper. "It's commonly accepted [in Latino culture] that if you're not the receptive partner, you're not gay. This is actually thought of as completely true!"

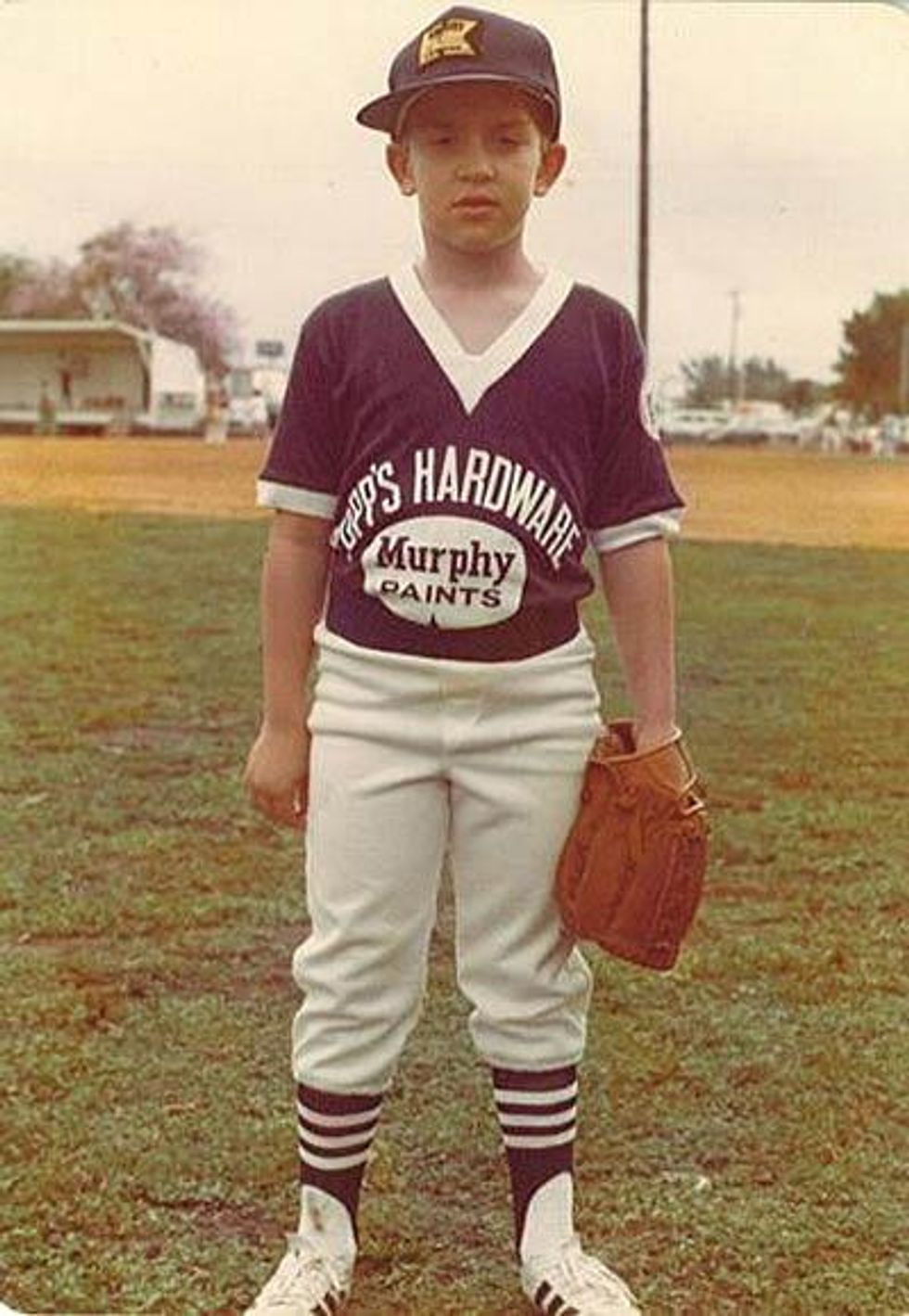

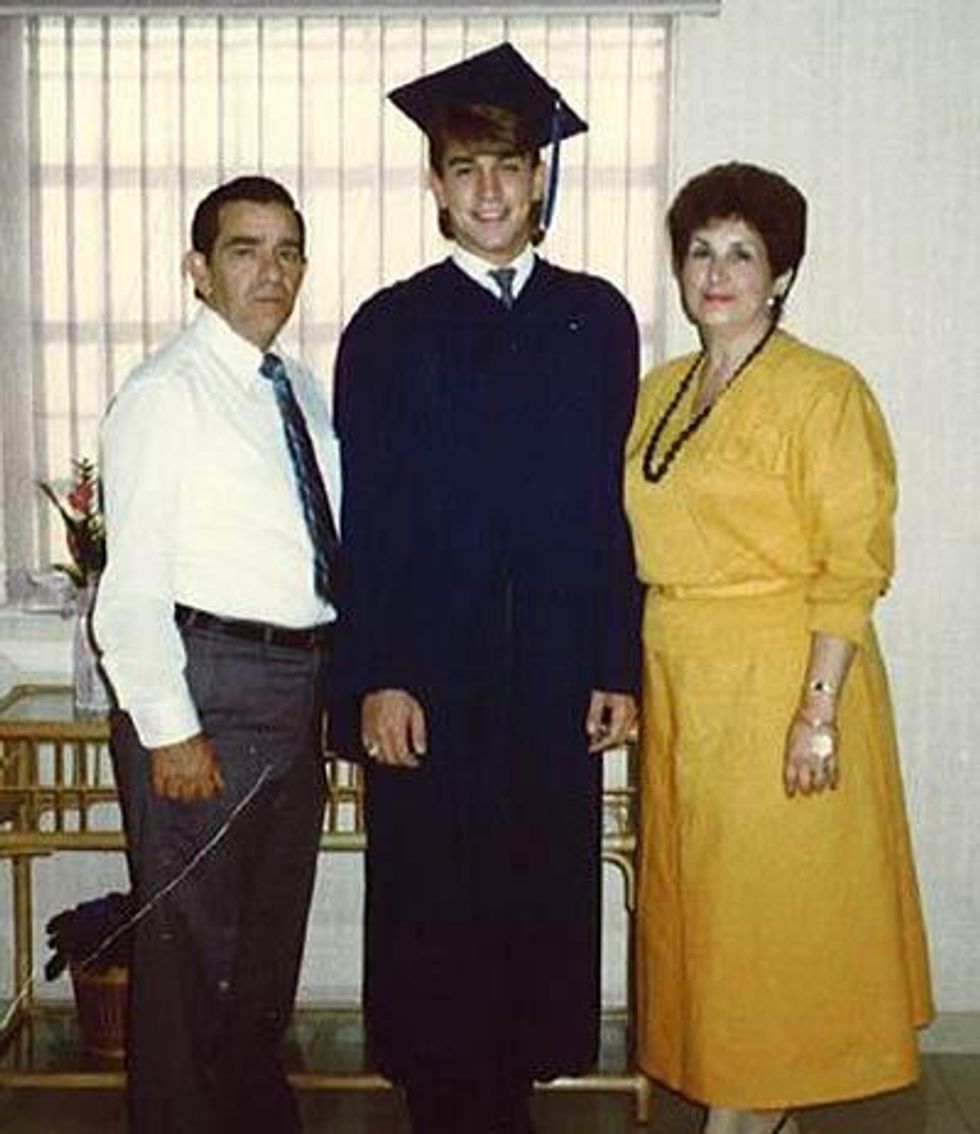

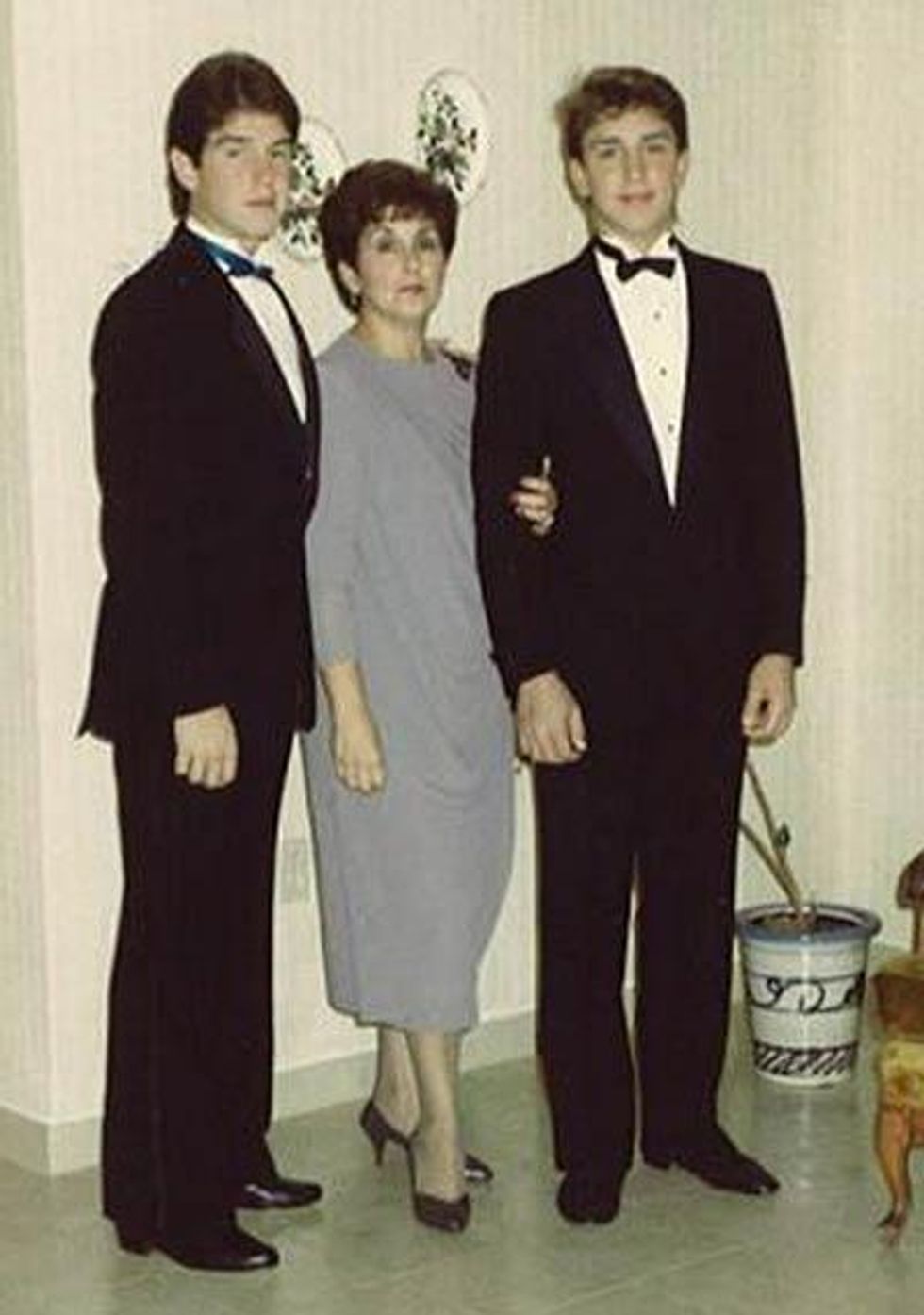

The rules of being a closeted, Spanish-born son of Cuban immigrants in America are not always clear or fair or set in stone. Like many young gay people, Ricky tries to play by the rules of acceptable behavior imposed by society and family for a boy growing into a man. He asks to be the "prince" of a young girl at her quinceanera, takes a female friend to prom and surprises her with champagne and a kiss, works out his body into a masculine mold, and flirts with but ultimately shies away from opportunities of love with other men, in fear of the consequences of breaking these rules.

In part, Blanco wrote his memoir in order to portray the "slow, slow, slow" process of coming out, which he describes as "a knowing without knowing."

"Coming out is really the end product of really a thousand, thousand, small, little episodes in your life -- how people challenge you. How people push back. How every time something happens, you open that door a little bit more, and you're able to have a conversation with yourself a little more. But it's terrifying," he says.

Like many a great bildungsroman, The Prince of Los Cocuyos (Spanish for "The Fireflies") portrays a character who feels torn between several different worlds and thus feels at home in none of them. His search for identity, belonging, and home is one that any reader, regardless of sexual orientation or ancestry, is one that anyone can identify with, particularly in the United States, the country of immigrants.

"The book is an American Dream story," Blanco affirms in between sips of coffee. "Part of the motivation for writing the book was to show that -- much like our president's story is, in a way, an American Dream story -- that this wonderful thing would happen to little Ricky."

"The book is an American Dream story," Blanco affirms in between sips of coffee. "Part of the motivation for writing the book was to show that -- much like our president's story is, in a way, an American Dream story -- that this wonderful thing would happen to little Ricky."

The "wonderful thing" is, in part, an answer to a question asked throughout the book: "Where are you from?" But this discovery would occur years and "three more books" later. It took a phone call from Obama and the task of writing an inaugural poem for a U.S. president for Blanco to come to terms with his identity.

"Am I American? Can I write this poem honestly? Do I really belong to this country?" were the questions Blanco recalls wrestling with at the time. "The experience was realizing I don't have to be Peter Brady or Marcia Brady -- that my story, my mother's story, was all a part of the grand American story. To say 'I am Cuban' and 'I am American' is the same thing in this country."

"I am American," he asserts. "'American' means all those things. But I gotta tell you -- I'm practicing getting used to saying that."

In his memoir, the question "Where are you from?" is perhaps asked most poignantly by someone who must have seemed the polar opposite to Blanco as a youth: Yetta, an older Jewish woman who has taken up residence in a dilapidated hotel in Miami Beach, the Copa, where Ricky's family stays for a holiday. Spurned by his older Cuban cousins, Ricky strikes up an unlikely friendship with the Polish-born immigrant, who sprinkles her dialogue with Yiddish like "mamele, meshuggener, schlep, schlocky," wears flashy jewelry, and enjoys foods like liverwurst, Reuben sandwiches, and pierogi.

Although outwardly different, young Ricky eventually comes to see the ties that bind. But the question she asks about his identity bothers him throughout his stay at the Copa. Since he was not born in Cuba, he does not share the memory or ties to his motherland held by his family, and it might as well be a mythic place to him. And the sword is double-edged. At one point, he expresses his concerns to Yetta about how his ethnicity and culture also prevents him from feeling completely American.

"Don't worry about it, bubbeleh," she advises. "Some days I feel Polish, some days American, and some days even a little cubana too. So what? So we're a little from everywhere -- not so bad I think, not so bad."

"My favorite piece was 'I'm a little from everywhere,'" Blanco confirms in the present day. "And aren't we all? At the end of the day, as you move more through life, you take little pieces of everything that you experience -- people we love, people we know, people we meet."

In one of the memoir's most emotionally resonant moments, Ricky has a reverie in which all time, space, and identity are conflated. His mother appears as "a little Polish girl in pigtails," Fidel Castro lunches at a Jewish deli, Yetta drives with his father in the family's cherished Malibu convertible. At these moments, Blanco's poetry shines through.

In one of the memoir's most emotionally resonant moments, Ricky has a reverie in which all time, space, and identity are conflated. His mother appears as "a little Polish girl in pigtails," Fidel Castro lunches at a Jewish deli, Yetta drives with his father in the family's cherished Malibu convertible. At these moments, Blanco's poetry shines through.

"That's sort of stream-of-consciousness," Blanco says, before drawing a parallel to the machinations of memory. "But that's how we operate in our mind. We don't have these clear, articulated images. Everything starts blurring, in a way. One moment you're thinking about the dog, and the next you're thinking about moving to L.A. In those moments are a great flurry of discovery ... it's an impression. It's a painting with a million different colors coming at you."

Blanco has carried the wisdom of Yetta into his adult years. Coincidentally, his husband, Mark, also has Polish ancestry. By sitting in on Thanksgiving and other holiday meals, he has observed that not every American has the Brady Bunch table spread that he saw on TV, and which so glaringly contrasted with his holidays growing up -- his Thanksgivings mixed turkey and pork, cranberry jelly and black beans, pumpkin pie and flan.

But the Pilgrims, Blanco points out, were like his own family -- immigrants and exiles from their native land. The first Thanksgiving was also a meeting of two different peoples who must have brought very different foods to the table but still found common ground.

"Since the day I stepped into that house and met his parents, that's actually when I really fell in love with him," Blanco says of his partner and his family. "That woman could have been my mother. It was the same set of values, the same sensibility of life. It was completely cross-cultural."

Immigration is an important issue for Blanco, who in the past has joined forces with Freedom to Work, most memorably in the production of a video poem, "Until We Could," that celebrated marriage between same-sex couples from every background. He enumerates the financial benefits Latino immigrants have brought to the country ("They have the buying power of India!") and speaks critically, but hopefully, about opposition to immigration.

"There's a lot of pushback. But that pushback is actually a good sign in some ways, because it means something is pushing forward," he says. "In a way, America is coming out of the immigrant closet. You see it reflected it on TV. In shows like Jane the Virgin, you actually have a Spanish-speaking character with subtitles! That's unheard of ... You have shows like The Goldbergs, Blackish -- bringing these generational issues where the parents are too 'black' for the kids and the kids are too 'white' for the parents."

"There's a lot of pushback. But that pushback is actually a good sign in some ways, because it means something is pushing forward," he says. "In a way, America is coming out of the immigrant closet. You see it reflected it on TV. In shows like Jane the Virgin, you actually have a Spanish-speaking character with subtitles! That's unheard of ... You have shows like The Goldbergs, Blackish -- bringing these generational issues where the parents are too 'black' for the kids and the kids are too 'white' for the parents."

These are themes much in common with The Prince of Los Cucuyos, which Blanco hopes to adapt into a television show, "like a Latino Modern Family," he asserts. One of his goals is to change the conversation on immigration, and a television show could not only broadcast to a large audience about the differences in cultures, but also the sameness, like the connection he experienced with Yetta many years ago.

"History moves very slowly," Blanco says. "Some of the same questions I've asked in my poetry and asked in my book are still some of the same questions that Whitman was asking. What is America? We may never have a final answer, or that answer keeps on changing. Look what's happened in the last 10, 15 years. If you really think about it, 10 years ago, I couldn't have been selected as inaugural poet. The country would not have been ready."

"It's like a nonprofit. ... You set a goal so lofty that it can keep you busy for a few thousand years," he concludes about the United States. "But there is a guiding light. And there's a core, fundamental understanding of who we are. Besides all the noise and all the rhetoric and all the weird politics and all the fighting, there's something, somehow, that stitches it all together."

Richard Blanco's new memoir, The Prince of Los Cocuyos, is now available from HarperCollins. Read an excerpt from "The First San Giving" here.

"Being gay is not the crime, if you read into my grandmother. It's being effeminate," Blanco interprets. "There's a layer of machismo relevant to Latino culture, where it's about this hypermasculine society. And the irony of a hypermasculine society, like the Greeks, is it is completely homoerotic."

"Being gay is not the crime, if you read into my grandmother. It's being effeminate," Blanco interprets. "There's a layer of machismo relevant to Latino culture, where it's about this hypermasculine society. And the irony of a hypermasculine society, like the Greeks, is it is completely homoerotic." "The book is an American Dream story," Blanco affirms in between sips of coffee. "Part of the motivation for writing the book was to show that -- much like our president's story is, in a way, an American Dream story -- that this wonderful thing would happen to little Ricky."

"The book is an American Dream story," Blanco affirms in between sips of coffee. "Part of the motivation for writing the book was to show that -- much like our president's story is, in a way, an American Dream story -- that this wonderful thing would happen to little Ricky." In one of the memoir's most emotionally resonant moments, Ricky has a reverie in which all time, space, and identity are conflated. His mother appears as "a little Polish girl in pigtails," Fidel Castro lunches at a Jewish deli, Yetta drives with his father in the family's cherished Malibu convertible. At these moments, Blanco's poetry shines through.

In one of the memoir's most emotionally resonant moments, Ricky has a reverie in which all time, space, and identity are conflated. His mother appears as "a little Polish girl in pigtails," Fidel Castro lunches at a Jewish deli, Yetta drives with his father in the family's cherished Malibu convertible. At these moments, Blanco's poetry shines through. "There's a lot of pushback. But that pushback is actually a good sign in some ways, because it means something is pushing forward," he says. "In a way, America is coming out of the immigrant closet. You see it reflected it on TV. In shows like Jane the Virgin, you actually have a Spanish-speaking character with subtitles! That's unheard of ... You have shows like The Goldbergs, Blackish -- bringing these generational issues where the parents are too 'black' for the kids and the kids are too 'white' for the parents."

"There's a lot of pushback. But that pushback is actually a good sign in some ways, because it means something is pushing forward," he says. "In a way, America is coming out of the immigrant closet. You see it reflected it on TV. In shows like Jane the Virgin, you actually have a Spanish-speaking character with subtitles! That's unheard of ... You have shows like The Goldbergs, Blackish -- bringing these generational issues where the parents are too 'black' for the kids and the kids are too 'white' for the parents."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered